Ravi Kumar of India and Anthony Munigety of Texas have been charged with committing various fraud schemes targeting primarily elderly victims and netting nearly $600,000.

Press Trust of India New York

An Indian national has been charged along with a US citizen for committing various fraud schemes targeting primarily elderly victims throughout the United States and netting nearly $600,000 from them.

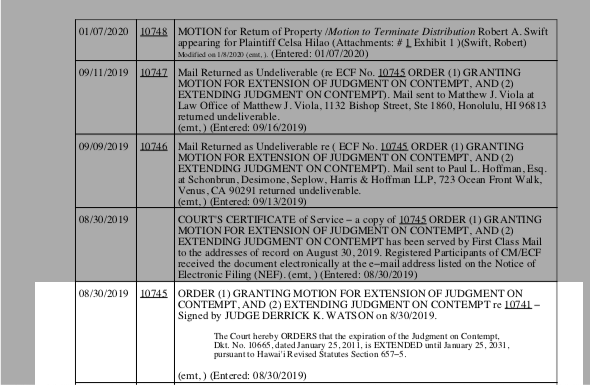

Ravi Kumar of India and Anthony Munigety of Texas have been charged in a 20-count indictment. Kumar is believed to be in India and considered a fugitive. A warrant remains outstanding for his arrest, the US Justice Department said Tuesday.

Munigety has been taken into custody on charges of obtaining over $600,000 from elderly victims throughout the country, US Attorney Jennifer Lowery.

Munigety and Kumar are charged with conspiracy to commit money laundering, 13 counts of wire fraud and six counts of money laundering. If convicted, they face up to 20 years on each count as well as a possible $250,000 maximum fine.

According to the allegations, the fraud ring operated out of the Conroe area in Texas and other locations in the United States and India. Munigety, Kumar and others allegedly committed various fraud schemes targeting primarily elderly victims throughout the United States.

The primary objective, according to the indictment, was to deceive victims by telling them a technical support company or other entities were purportedly helping them with their computers.

They would allegedly trick victims into believing they had been erroneously refunded or overpaid and needed to return the overpayment. The indictment alleges they were able to gain access to a victim’s computer which enabled Munigety, Kumar and others to move funds between or wire transfer monies out of their accounts, according to the charges.

Once that occurred, Munigety and others would keep a portion of the money and wire the remainder to Kumar in India, according to the charges.

As a result of their scheme, Munigety and others allegedly received over $600,000 from elderly victims.