It’s Not Where the Cookie Crumbles: Memoir as a Process of Enlightenment, Emancipation and Reclaiming Innocence

Former students from my Memoir Writing and "other writing" classes working up the gumption to "tell their stories"

It truly is a liberating process, and an emotional landmine. Imagine, strangers, adults, grayhairs, all coming from different avocations, life experiences, even abilities to draw words onto “paper,” hanging out for two hours a day, once a week, eight weeks, with ME!

They stuck with me, man, for weeks, and then they came back for more at this community education class through the Oregon Coast Community College. I take my hats off for the lot of them hanging in there with this dude, Man Lost of Tribe: Preface: Terminal Velocity—A Man Lost of Tribe

And I did bring up Palestine and the mass murder and genocide. But, here, your link to the Show on Memoirs and Growing Old.

*****

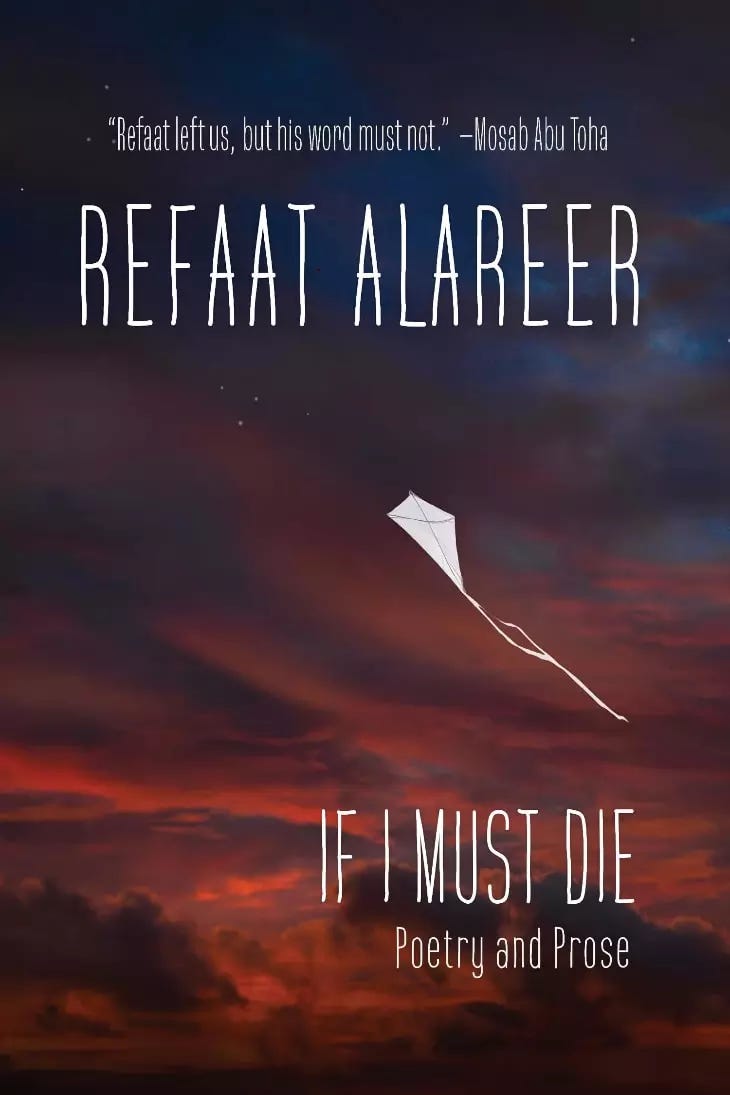

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story —

Refaat Alareer believed in the power of stories and the vital necessity of mastering language (specifically, English) sufficiently to tell those stories in an honest and compelling manner. He grew up on the stories of his mother and grandmother, and he in turn entertained his children at night with stories. (His TED Talk on the power of storytelling is worth listening to.) But following October 7, he was unable to continue this practice. In several essays collected in the anthology, he wrote poignantly about the ways in which living in the context of genocide charged his interactions with his children, as normal gestures or words of affection could suddenly be understood as final goodbyes and trigger alarm.

Preface: Terminal Velocity—A Man Lost of Tribe

What is a life, revealed? What is this idea of truth, the unadulterated history in one’s narrative? The baggage, the contexts, the points of view, dredged into one’s psychological state, all the trauma of simple moments in a boy’s or man’s life, boy-to-man and man-to-boy sense of things, are these parts of the lens one should focus in a process of a looking backward (writing it) and then forward to draw lessons learned and still to be revealed (as an organized, somehow, autobiography)? Is it important for someone like me to write a “biography” even at all without the pedigree of “someone who’s big, still rising, haven risen and/or now fallen from grace,” or in this case the anti-autobiography of a simple man, Willy Loman sort of teacher, even without a bone of celebrity in my body?

“I don’t say he’s a great man. Willy Loman never made a lot of money. His name was never in the paper…. But he’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He’s not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person.” – Linda Loman, Death of a Salesman

Is the crucible of democracy in the wasteland of American white manifest destiny the very essence Arthur Miller was attempting by addressing in the simple cut of a man in his play, a salesman separated from tribe, from any real sense of giving back to community. The lost and plagued American displaced inside his own land, in his mind, empty of an alternative to this denuded existence selling or hawing or moving information around for deceitful misanthropic companies and corporations?

The body of this long-form writing is a 30-part “series” possibly distilled into fictional fusions—captured life moments, galvanized to the heart of seeing creatively in a pretty messed up world.

The body of this long-form writing is a 30-part “series” possibly distilled into fictional fusions—captured life moments, galvanized to the heart of seeing creatively in a pretty messed up world. I believe this to be one of the most gut-flooding truth seeking to some of us, painted characters and landscapes, conflicts, yet the dog of the lamentation, those roses that shed blood, tears from the prickly pear, the ghost inside cenotes.

The Mayan legend is close to me since I lived in the Yucatan for a while and returned several times: women, sisters – Xtabay the sinner and Utz-Colel the good—in Maya land, come to the male traveler, or the drunkard or just one who laments some image of beauty lost. Lured into the sacred well, the flowers sweet and succulent, and this glorious angel (the warts and sag of skin like the witch not revealed yet) entwines him in her long black hair, and, in the morning, if he is lucky enough to make it out with his life, he finds the morning flooded with sadness, cruda, which is the hangover of unbearable light of life to never pass through that crucible of potential and idealized beauty.

So, as this unfolds, in serialized life form, quickly, the reader may be entering a carnival, where hummingbirds make nests in the bleached rib cage of grandpa out back helping hold up the hydrangeas. There will be allusions and pathways marked. There will be the flow of a creative writer. The confusion of age in a time long shriveled into the amnesia of our collective lobotomy.

The one-toothed lady from Hanoi, shriveled in her 70s, but there, $3 massages, on China Beach, holding the man’s manhood, the fragrance of sea and bottled passion fruit singeing the neck hairs of some battle-fatigued old timer wondering if he immolated the woman’s daughters and sons, brothers and grandchildren.

Napalm mornings and nights lifted by fruit bats in the hundreds. The memory of my life is energy, like ball lightning one moment, then like a tree holding orchids a hundred years old. Reflections in the koi pond come at night, in dreams, as coral reefs are mowed down by giant parrot fish and dredges from eco-miners.

Time is compressed and flipped, and images are truths, poems the shouts in the night in the careening howls of wolves released on Nez Perce lands in Idaho, and then the lies that make up the fabricated, truths, twisted deceptions reflected through the parallax to become something of a tribute to one man’s survival, which is in the end the very essence of finding death withheld.

What will be true in these 30 parts is fantastical drawn from the mundane, the nanosecond of death revealed in a lifetime under a sheltering moon.

I like Mark Twain, and boy could this world use another one, now, and Gore Vidal, or Zora Neale Hurston. Here, though, some prescient words about autobiography from Twain:

“An autobiography is the truest of all books; for while it inevitably consists mainly of extinctions of the truth, shirkings of the truth, partial revealments of the truth, with hardly an instance of plain straight truth, the remorseless truth is there, between the lines, where the author-cat is raking dust upon it which hides from the disinterested spectator neither it nor its smell (though I didn’t use that figure)—the result being that the reader knows the author in spite of his wily diligences.” —Letter to William D. Howells, 14 March 1904

It’s absolutely truth that the reader has to work at unmasking the masks and then read between the lines of anyone’s autobiography. My goal in this work is to even go a step further and fuse streams of consciousness and great leaps in narrative structure to suture up what can be for me and others a disgorgement of what is revealed inside a nasty system as we pledge allegiance to North America, these United States, in whatever form that allegiance takes. I am not talking about patriotism or nationalism, to be sure. Here, Twain, on autobiography, his, which is relevant to me, to my small life compared to Samuel Langhorne Clemens, but most great books are repositories of vivid truth about even the smallest man or woman notched into capitalism:

“This autobiography of mine is a mirror, and I am looking at myself in it all the time. Incidentally I notice the people that pass along at my back — I get glimpses of them in the mirror — and whenever they say or do anything that can help advertise me and flatter me and raise me in my own estimation, I set these things down in my autobiography. I rejoice when a king or a duke comes my way and makes himself useful to this autobiography, but they are rare customers, with wide intervals between. I can use them with good effect as lighthouses and monuments along my way, but for real business I depend upon the common herd….

An autobiography that leaves out the little things and enumerates only the big ones is no proper picture of the man’s life at all; his life consists of his feelings and his interests, with here and there an incident apparently big or little to hang the feelings on.” – Mark Twain’s Autobiography

This is a time and age when the mainstream publishing world is looking for the next big thing, the expose, some catharsis from some celebrity, or famous person from any walk of life, more so from the mover and shaker in the millionaire or billionaire class, possibly some jock or military general or politico who got caught, or just gets the stage because of all the collateral damage they caused in their service to the paymasters and dispiriting guiders – CEOs, Spooks, Presidents, Despots. Some Bruce-to-Caitlyn aberration, or philandering Patraeus, some mothball-brained Kissinger, Johnny Depp, or that hyper-Breaking Bad-or-Orange is the New Black sort of story-boarding memoir thing?

Life Uninterrupted, a solemn credo tied to anti-authoritarianism, against the tide of cultural devolution, consumerism, from a precariate, one of the truly precarious workers in this trickle-down and buckle-up Consumer Free-to-Exploit Market System that has banked on ignorance, amnesia, fear and loathing, non-participatory “democracy, racism-sexism-otherism to run a majority of the workers into the ground .

In the old days, magazines like Life or Look or Harpers or Any Number of Periodicals That Have Been Scarfed Up by Media Moguls, they serialized long-form, novellas and even novels. Here, thanks to Dick and Sharon and their LA Progressive, I have been offered up a section of the online magazine. Can I live up to the challenge of daily distilling “the things of life” to make all lives relevant, to meet a weekly deadline? From me, a lowly activist and pretty well-read and well-traveled and well-shaped writer with a few low-hanging fruit laurels. Amazing how in the slip-stream of life, six degrees of separation reverberating in my life, others’ lives, that Dick and Sharon are giving me a chance and the challenge to write a “memoiry” kind of new journalism auto-biography as something more than expressive and cathartic, or wholly self-indulgent. But as a clarion call to a certain rarefied group of readers who might learn from the scattershot world I have lived in, thus far, 59, and counting.

I will journey with a reader into psycho-political dynamic seascapes, flowing with a sense of splendor at some things and places I have been lucky to encompass in an undertow that for me is a natural place to be inside a tide pool of ebb and flow, since I am also a seasoned diver who has seen a few riptides and swarming packs of hammerheads.

Travelogue and full of internal dialogue, with a trade-wind of constant magic realism, lots of punctuated stream of consciousness and a real concern for reaching audience and listener, so the form does not overtake the language and the lessons tied to universal rules and goals.

In a nutshell, I am tasked to write my life as it is in some fashion in 30 weeks, an assignment that I have to utilize daily since my life is not written down as such. This is more than journaling, but at times it will feel like a journey into the now, with folded chapters back.

A life doesn’t start Feb. 6, 1957, in San Pedro, California. That birthing moment when I exploded out of womb six weeks premature, blue baby with mama’s cord wrapped around the neck twice, is pressed into a continuum that goes back to tribes long forgotten, to ancestors from Ireland and Germany. Pressed into the DNA of floating through the laws of time, the influences of nature and nurture, all those small traumas, and larger ones.

Maybe this attempt will be a fusion of fantasy and fiction, cemented to some concrete perception of the world I created and continue to create. Here, Lidia Yuknavitch

“I think our identities—the ones we live in the real world—are really made partly from stories that we build up around ourselves—necessary fictions—so that we can bear the weight of our own lives. We like to call these “truths” or “facts” or “selves,” but I maintain that they are fictions. Fictions for instance called “mother” or “wife” or “lover” or “teacher” or “writer.”

I think we understand our own life experiences in narrative terms. If you consider that idea for a moment, we are walking novels. No one has a pure identity. Everyone has an identity made from everyone they’ve ever known and loved or hated, and from every experience they could process and withstand, happy or sad, arranged in memories, otherwise known as stories.”

I am a walking set of novels, and a few have ended up on the trash bin of US publishing houses, and my former agent, Jack Ryan, always pressed upon me that I was ahead of my time, that my novels he tried schlepping were over the heads of the Vassar and Brown university interns looking over “new” novelists’ work with not much eye toward form and subject outside what was tracking that year in publishing circles.

The embedded lie is almost everything in America, and so working here and living and grappling against the vicissitudes of a vulture, parasitic capitalism and invented history that is our way of living and doing business, one has to develop more than just a bipolar way of dealing with so much corruption and anti-egalitarianism.

My call of duty is to get something right, something outside the norm that we see as storytelling and dramatic novel writing. I want to pledge allegiance to the profane and prophetic, and still have the pleasure of enjoying staking out emotional, intellectual and cultural space.

We are the sum total of everyone else’s projections, those parts that jigger the reality based belief system that there are clear boundaries between right and wrong, success and failure, happiness and sadness, sanity and insanity.

This writing is part of the great wind of time, full of limited perspectives, but something holy to the atheist’s regard for humanity starving for communitarianism. From the Heights of Macchu Picchu to the Power and the Glory, we are all living “under a volcano” as the “memory is fire”.

*****

And tell me everything, tell chain by chain,

and link by link, and step by step;

sharpen the knives you kept hidden away,

thrust them into my breast, into my hands,

like a torrent of sunbursts,

an Amazon of buried jaguars,

and leave me cry: hours, days and years,

blind ages, stellar centuries.

And give me silence, give me water, hope.

Give me the struggle, the iron, the volcanoes.

Let bodies cling like magnets to my body.

Come quickly to my veins and to my mouth.

Speak through my speech, and through my blood.—Pablo Neruda

Or, beyond, inside the bottle of Mexico, too, Malcolm Lowry:

“There was something in the wild strength of this landscape, once a battlefield, that seemed to be shouting at him, a presence born of that strength whose cry his whole being recognized as familiar, caught and threw back into the wind, some youthful password of courage and pride—the passionate, yet so nearly always hypocritical, affirmation of one’s soul perhaps, he thought, of the desire to be, to do, good, what was right. It was as though he were gazing now beyond this expanse of plains and beyond the volcanoes out to the wide rolling blue ocean itself, feeling it in his heart still, the boundless impatience, the immeasurable longing.”—Under the Volcano

Caught inside the subterranean magic of history foretold:

“While we can’t guess what will become of the world, we can imagine what we would like it to become. The right to dream wasn’t in the 30 rights of humans that the United Nations proclaimed at the end of 1948. But without it, without the right to dream and the waters that it gives to drink, the other rights would die of thirst.” —Eduardo Galeano, author of Memory of Fire

Captured by the essence of the puritanism of capitalism and religion intermingled like some unholy alliance of the captured and the corrupted:

“There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” — Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory

This will be a process of regaining a future, remembering the links of the past are part of a continuous chain, pulling and pulling me deeper into my past, which is my future, and I hope the process is well-suited for a reader, many readers.

Paul Haeder, June 24, 2016

*****

Okay, so Brenda and Melodie are on my KYAQ show, coming out on the air, 91.7 FM, Wednesday ,Feb. 18, the start of the new Chinese year, Fire Horse:

What Makes the “Fire Horse Year” (赤馬年) Unique?

- Passion & Enthusiasm: A fervent drive and zest for life.

- Dynamism & Innovation: The spark that ignites novel ideas and propels decisive action.

- Brightness & Clarity: Illuminating paths forward, fostering optimism and clear vision.

- Assertiveness & Leadership: The courage to lead, inspire, and take initiative.

This “Fire on Horse” combination significantly amplifies the zodiac sign’s natural traits, foretelling a year of heightened activity, rapid progress, and potentially transformative changes. The term “赤馬” (chì mǎ), or “Red Horse,” eloquently captures this. “赤” (chì) signifies red, a color deeply revered in Chinese culture for symbolizing good fortune, joy, and prosperity. Therefore, a Red Horse is more than just a magnificent creature; it is an icon ablaze with vitality and auspicious tidings.

*****

I’ll take these stories, these ancient myths, over ANYTHING western culture has shoved down our throats:

- Folktales & Mythology: Legendary horses, including the loyal White Dragon Horse (白龍馬) from “Journey to the West” and the fabled Thousand-Mile Horse (千里馬), capable of traveling immense distances, further cement the horse’s image as a heroic figure and a symbol of extraordinary ability. And of course, the legendary Red Hare (赤兔馬), the formidable steed of the warrior Guan Yu, renowned for its unparalleled speed and loyalty – a perfect ancient counterpart to our vibrant “Red Horse” theme.

Ahh, the memoir, in Western tradition:

- “I gather together the dreams, fantasies, experiences that preoccupied me as a girl, that stay with me and appear and reappear in different shapes and forms in all my work. Without telling everything that happened, they document all that remains most vivid.” bell hooks, author of Bone Black

- “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

- “Everybody needs his memories. They keep the wolf of insignificance from the door.”Saul Bellow

- “Autobiography may be the preeminent kind of American expression.” Henry James

- “It’s amazing how you remember everything so clearly,” a woman said…”All those conversations, details. Were you ever worried that you might get something wrong?” “I didn’t remember it,” Lucy said presently. “I wrote it. I’m a writer.” Ann Patchett, Truth and Beauty

- “It is not my deeds that I write down, it is myself, my essence.” Montaigne

- “Sick of being a prisoner of my childhood, I want to put it behind me.”

Clive James, Unreliable Memoirs - “Isn’t telling about something—using words, English or Japanese—already something of an invention? Isn’t just looking upon this world already something of an invention?”

Yann Martel, The Life of Pi - “There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.” Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory

- “The tales you are about to read are the truth, practically the truth, and nothing less than a half-truth…” Nick Trout, Tell Me Where it Hurts: A Day of Humor, Healing and Hope in My Life as an Animal Surgeon

*****

Here, one woman’s top Memoirs for 2025:

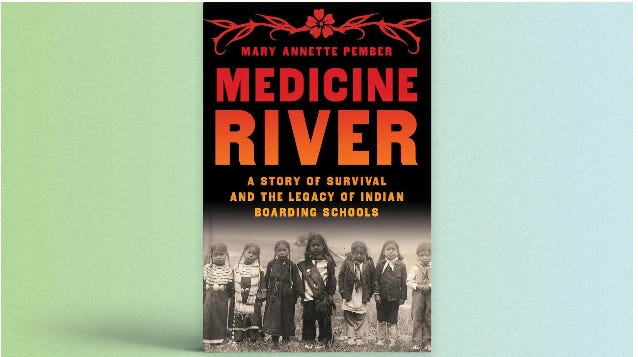

10. Medicine River: A Story of Survival and the Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools, Mary Annette Pember

Mary Annette Pember’s mother never wanted to answer her daughter’s questions about what she had experienced during her eight years at St. Mary’s Catholic Indian Mission School. As a result, Pember, a journalist and national correspondent with ICT News and a citizen of the Red Cliff Band of Wisconsin Ojibwe, was unable to fully grasp her mother’s trauma and the impact it had on their family. After her mother’s death, Pember felt she needed to know what happened to her in order to better understand her own place in the world, which led her to research the boarding schools where countless Native children, including her mother and grandmother, endured years of hardship and abuse. She situates her family’s story within the broader history of these government-sponsored institutions as she grapples with both the trauma of family separation and her own complex relationship with her mother. Pember’s search supplies her with some needed clarity, while her exploration of her Ojibwe culture—and bearing witness to her people’s ongoing capacity for joy and survival—brings her a measure of healing.

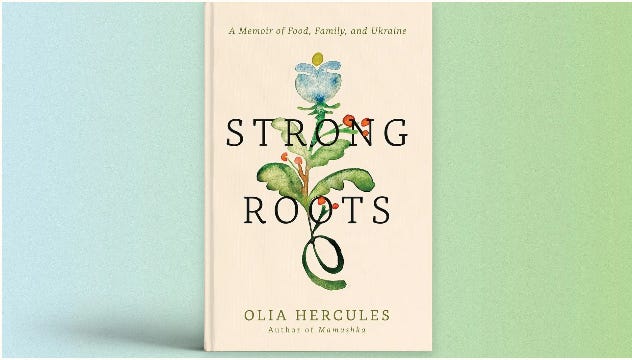

9. Strong Roots: A Memoir of Food, Family, and Ukraine, Olia Hercules

When tending rose bushes, Olia Hercules’ maternal grandmother Liusia instructed her family to “look at the roots”—if they are strong enough, she would say, even petals and stems lost to storms can grow back. In Strong Roots: A Memoir of Food, Family, and Ukraine, Hercules, a chef and author who was born in Kakhova and now lives in London, writes a work of memory, love, and quiet defiance. She names what her family and others have gone through since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine: her parents had to flee their home; her brother joined the defense forces; their hometown flooded after Russia destroyed a nearby dam. But the heart of her book is found in the resilience of her ancestors, whose legacy Hercules holds closer than ever. Amidst a war that hasn’t ended, what she eventually writes her way toward is not peace or resolution, but a ringing assertion of life: “Now I know that we are not victims. And we are not just survivors. We, Ukrainians of many ethnicities, cultures and histories, are united…. And here I am, living and breathing, writing these words for you, dear reader, to feel and understand our story.”

8. Articulate: A Deaf Memoir of Voice, Rachel Kolb

What does it mean to know and claim your voice, to be articulate, as a deaf person in a culture that often prioritizes hearing individuals and the spoken word? In this engrossing debut memoir, writer and scholar Rachel Kolb deftly combines personal storytelling and cultural commentary on deafness and disability, encouraging readers to consider the vast possibilities of language, communication, and dialogue—including the opportunities we might miss if we exclusively focus on verbal and hearing-dominant interactions. “Our ideas about fluency and sameness are…modern-day fictions,” Kolb writes, “extensions of those notions we’ve inherited about the normal and the standard and the typical…. But language, by its very nature, blooms from far more varied ground—which, to me, feels like its greatest miracle.” Curious and contemplative by turns, Articulate will make you think about self-expression, accessibility, and connection in new ways.

7. Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed, and Lost Idealism, Sarah Wynn-Williams

Sarah Wynn-Williams was a true believer in Facebook and its potential to “make the world more open and connected” when she pitched herself into a job as the company’s Manager of Global Public Policy in 2011. But what she once viewed as a dream role eventually gave way to a nightmare as she realized the extent to which what she describes as “a lethal carelessness” seemed to rule the company’s culture. In her memoir, Wynn-Williams portrays Facebook leadership as irresponsible, misogynistic, and power-obsessed; by the time she writes about founder Mark Zuckerberg being confronted with Facebook’s alleged role in Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, readers probably won’t expect much meaningful reflection or accountability in the company she refers to at one point as an “autocracy of one.” Wynn-Williams, for her part, does seem willing to interrogate her past aspirations: “I was part of it. I failed when I tried to change it, and I carry that with me.” While she is unafraid to name names or call out feckless behavior, it is the openness, warmth, and wit of her narration—all the more evident against the backdrop of a frequently absurd working environment—that makes her memoir a compelling read.

6. Memorial Days, Geraldine Brooks

As I read Geraldine Brooks’s memoir, I kept thinking of something a friend said to me while I struggled to complete the many administrative tasks triggered by my mother’s death: “No one warns you that death comes with a checklist.” Brooks begins with the moment when everything in her life changed: an emergency-room physician in Washington, D.C. calls to tell her that her 60-year-old husband, Tony Horwitz, has died suddenly while on a book tour. After this shock, the “first brutality” in “a brutal, broken system,” she cannot give into the need to scream or cry or collapse, because there is so much she must attend to. This cascade of responsibilities, as well as what Brooks describes as the “endless, exhausting performance” of life after a loved one’s death, will ring true to anyone who has suffered an unexpected loss. It is only when she travels to a remote island off the coast of Australia that she is able to mourn her husband. In Memorial Days, Brooks honors the life they shared and reclaims “something that our culture has stopped freely giving: the right to grieve.”

5. Nothing More of This Land: Community, Power, and the Search for Indigenous Identity, Joseph Lee

In Nothing More of This Land: Community, Power, and the Search for Indigenous Identity, Aquinnah Wampanoag author and journalist Joseph Lee shares the history of his family and his tribal community on the island of Martha’s Vineyard—known to Wampanoag people as Noepe—and reflects on questions of sovereignty, tradition, and belonging in Native communities from Oklahoma to the Pacific Northwest to the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. Lee brings his expansive journeys and conversations to life in this consistently thoughtful, accessible narrative that blends cultural history and memoir, research and reportage. Clear-eyed about both the destructive legacy of colonialism and the complications and contradictions often forced upon those working to challenge it, he positions himself as a curious and deeply engaged fellow learner, inviting readers to explore questions of community and identity along with him.

4. The Waterbearers: A Memoir of Mothers and Daughters, Sasha Bonét

“Each generation of women in my family seeks to transform realities,” Sasha Bonét writes in her exquisite memoir, “but somehow we always find our way back to what we know. And we come from a long line of Louisiana women who traversed these troubled waters of the South.” The Waterbearers: A Memoir of Mothers and Daughters is both the story of those who raised Bonét—the Black women in her family who fought with everything they had to build lives and legacies for themselves and their children—and the story of our country; as she notes, the waters she and her family have crossed can also “tell you the true history of America.” A lyrical, unflinching exploration of motherhood, love, and survival across generations, The Waterbearers is a meditative and unforgettable read.

3. Mother Mary Comes to Me, Arundhati Roy

After the death of her mother, Mary Roy, in 2022, novelist Arundhati Roy felt “heart-smashed” and “unanchored”—and also somewhat surprised at the depth of her own devastation. At 18, Roy had declared her independence from her mother, the strong-willed founder of a school who was determined to “make space for the whole of herself” in the world. Their relationship was never easy, and for years Roy had to love her formidable, sometimes terrifying parent “from a safe distance.” In Mother Mary Comes to Me, she tries to make sense of who she is after the loss of the woman she calls “my shelter and my storm”—and around whom, she also recognizes, she learned to construct her own life and identity. Writing of how she worked over the years to try to accommodate and understand her mother, Roy recognizes that her writing itself is yet another kind of inheritance: “I turned into a maze, a labyrinth of passages that zigzag underground and surface in strange places, hoping to gain a vantage point for a perspective other than my own. Seeing her through lenses that were not entirely colored by my own experience of her made me value her for the woman she was. It made me a writer.”

2. The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir, Martha S. Jones

In the opening pages of this powerful and contemplative memoir, historian and author Martha S. Jones recalls how a college classmate once mistook her for white during a presentation on Frantz Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism in their Black sociology class. Though the two later became friends, she never forgot his accusation: “Who do you think you are?” In The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir, Jones answers this question on her own terms, painstakingly researching and tracing the story of her family since the days when her oldest known ancestor, Nancy Bell Graves, was enslaved in Kentucky. She shares a photograph of Graves at the age of 80, noting that “her skin was closer in tone to the white bonnet on her head than to the deep, rich dye of her… dress,” and states that “Nancy bequeathed to us not only her portrait but also the trouble of color—somewhere between too little and too much of it.” Yet Jones does far more than find and introduce us to her dynamic, determined forebears, many of whom were also “caught up along the jagged color line”; in pursuing a richer and more nuanced family history—one that she herself can hold onto and share in—she shows us what it means to be in deep, earnest conversation with one’s ancestors, and to seek truths beyond the bare facts of their lives or the circumstances they were born into. Hers is a book that, she explains, “emanates from longing”: to better comprehend those she came from, to learn from them, and to know her place among them.

1. Things in Nature Merely Grow, Yiyun Li

“This is not a book about grieving or mourning,” Yiyun Li writes in Things in Nature Merely Grow, the remarkable book she wrote for James, her son who died from suicide in 2024. Li knew that she would write a book for James, as she had for his older brother Vincent, whom she lost to suicide in 2017. But she also knew that James, unlike Vincent, “would not like a book written from feelings.” In order to find words for her younger son, Li felt she had to try to “live thinkingly,” as he did: holding onto logic, reason, facts. Her book, while starkly, brutally honest, is not overly emotional; nor does it engage in “questions of whys and hows and wherefores or the wishful thinking of what-ifs”—because such questions would seem to argue against the irrefutable fact of James’s death, and would thus be “a violation of [his] essence.” Instead, it is a work of profound and purposeful consideration, written from the abyss in which Li finds herself: “If an abyss is where I shall be for the rest of my life, the abyss is my habitat. One should not waste energy fighting one’s habitat.” Not everyone will feel they have the capacity for the kind of “radical acceptance” Li writes about, but no reader could be unmoved by her tenacious search for understanding; her commitment to the truth of her sons’ lives; her need to find “the most straightforward language” for a loss that seems unfathomable, despite knowing that words so often fall short.

Top Ten from Nicole Chung, author of the memoirs A Living Remedy and All You Can Ever Know

*****

And there are always side trips, footnotes, more clamoring and chaos in the life of a Man Lost of Tribe. You’ve read about me being cancelled, for a talk I was asked to give based on my perceptions why we have the death of journalism, death of critical thinking, death of basic history and context.

We DO have the luxury to write, no, in the cradle of Western UnCivilization?

And, Viet is someone I have pushed for the memoir writing class:

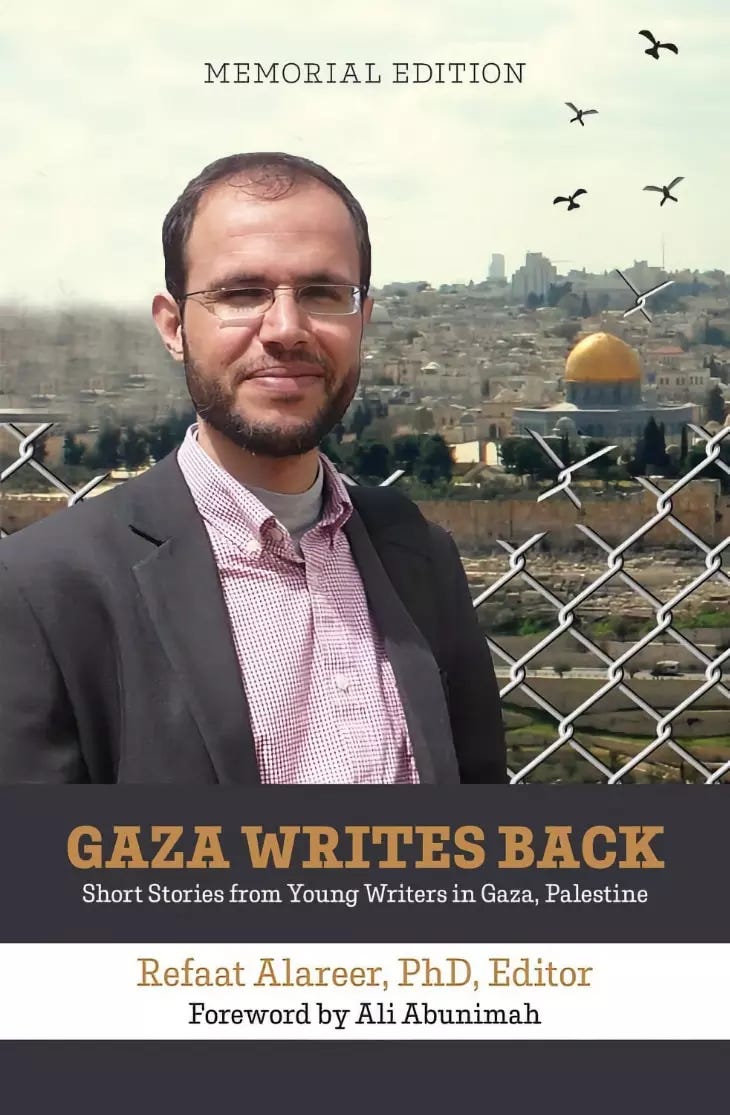

Suchitra, Bhakti, and Madhuri invite writer, editor, and translator Yousef Aljamal for a moving and intimate conversation that honours the life, work, and enduring legacy of the late Refaat Alareer — Palestinian writer, poet, professor, and beloved mentor assassinated by Israel in December 2023. Yousef was Refaat’s student, collaborator, and close friend. Yousef assembled and edited the book If I Must Die: Poetry and Prose by Refaat Alareer which was published early this year.

He speaks with clarity, wit, and tenderness about the man whose imagination helped birth an army of writers out of besieged Gaza, including the powerful collection Gaza Writes Back Together, the hosts and Yousef reflect on Refaat’s literary and political ethos — his belief that storytelling is resistance, that fiction outlives fact, and that freedom begins in the imagination.

They unpack how Refaat fused humour with rage, literature with politics, the classroom with the battlefield. The conversation also considers the role of US universities, the complicity of elite institutions, and the radical hope fuelling a generation of students who refuse silence in the face of genocide.

The title of the episode cites Susan Abulhawa’s introduction to the book If I Must Die where she writes that Refaat’s death reminded her of Berta Cáceres of Honduras, “another indigenous leader who, like Refaat, was murdered because the light of her being shone too brightly…When she died, the rallying cry of the thousands who loved and followed her was, “Berta no murió, se multiplicó!” Likewise she says, “Refaat did not die, he multiplied!”

Israel’s barbarity to murder people in Gaza and to sever the connections between people and people, and between people and land, and between people and memories, will never succeed. I lost my brother physically, but the connection with him will remain forever and ever. — R.A.

Susan Abulhawa Remembers Refaat Alareer: Poet, Teacher, Husband, Father: On December 7, 2013, a Ph.D. student in Malaysia reached out to me by email because he was writing a research paper on a section of Mornings in Jenin. He told me that he had taught my novel at the Islamic University of Gaza, and he hoped to get my thoughts on his thesis. His name was Refaat Alareer. We corresponded on the topic and kept in touch. We became friends and comrades, and I came to love, respect, and value him.

Exactly ten years later, on the morning of December 7, 2023, I awoke to news that Israel had killed Refaat. They targeted the home where he had taken refuge the previous day, and it took a day for news to trickle out of Gaza’s blackout. I sat in front of my screen, red-eyed and in shock, searching for remnants of Refaat in my own life—signed books, notes, photos, messages, and emails.

I quickly discovered that the email in 2013 was not my first encounter with Refaat. I found an earlier message, from 2011, in which I told a friend that I had cried over a beautiful tribute to Vittorio Arrigoni, the Italian solidarity activist who was killed in Gaza. The tribute was written by a Refaat Alareer. I had not made the connection until I went searching for him after Israel killed him.

Much of the correspondence between Refaat and me was conducted over Twitter (now rebranded as X). But my account was permanently suspended in early 2023 after Zionists launched a campaign to have me canceled, and all of those messages were stolen from me. Although that account had contained an audit of my thoughts and activism for at least a decade, I never mourned its loss until I needed to re-read my exchanges with Refaat.

Shortly after Israel launched its genocidal assault on Gaza, Refaat urged me to create a new Twitter account. Always trying to make our case to the world, he said, “we need your insight there,” and he suggested a handle for the account. I immediately did as he counseled and sent the link to him. His response: “Got your first 4 follows [wink emoji].”

I believe some part of him knew what was to come. Still, he was planning for things “after the genocide stops.”

He was smart to have multiple accounts, prepared with backups in case of social media assaults. His mind was unbreakable and beautiful and fine. Online trolls and cancellation campaigns were no match for him. But he had no defenses against bombs. The most dangerous thing he had was “an expo marker,” as he told Ali Abunimah in his last interview with the Electronic Intifada. He said he would throw it at soldiers when they broke into his home. But he would not even get the satisfaction of that imagined small moment of self-defense. Israelis, cowards as they are, targeted him from the sky.

Three days before Israel murdered Refaat, he sent me a video of what remained of his home and the lifetime of memories it held. The video records three and a half minutes of him walking through unimaginable destruction in Tel al-Hawa, narrating the life that used to be, pointing to pieces of things once whole, clean, functional. A sofa, where he had perhaps lounged lazily countless times, maybe with a book, his children climbing on him; a broken window frame that brought breeze and sunshine and kept in the warmth of the family he loved and lived for; a piece of cloth, like the one in the poem he wrote for his daughter Shymaa,“If I Must Die.”

The heartbreak he must have felt is difficult to fathom. Refaat was no stranger to injustice and profound loss. Israel murdered his brother and at least thirty members of his wife’s family in 2014, one of many aerial pogroms committed against Palestine, Gaza in particular. But “this [time] is different,” he told me in a text on October 14. He wrote, “it’s going to be even worse. We are bracing for that. We have no way to defend ourselves.”

I believe some part of him knew what was to come. Still, he was planning for things “after the genocide stops.” In particular, we talked about the Gaza Zoo. It pained him that many of the animals died because they had gone without water or food for weeks. Two days later, on October 16, I messaged to check on him after Israel began bombing Shujaiya. Of the people murdered that day, he said, “it’s my relatives. But I don’t know who. Calls can’t reach.”

In the video, Refaat continues walking, narrating what we can all see but cannot truly comprehend. Hearing his voice in that recording now is strangely soothing, as if he’s not really gone; as if he might answer if I call him. He stops where books are scattered on the ground. “Some of these are mine,” he says, sifting through tattered, torn, and dusty covers.

Refaat believed there was great value in speaking and writing to the people of empire to lay bare our humanity before them.

The first thing he chooses to pick up, the thing he tries to salvage, is a book he finds from his destroyed library. It’s an unabridged copy of Gulliver’s Travels. He had read it a few times, I remember him telling me years ago. In vain he tries to knock off the dust and debris, but he carries it with him nonetheless. I think the loss of his library broke his heart in ways other losses had not. His books were the accumulation of his intellectual labor, years of reading, thinking, and journeying the world through the written word. Books were integral to his identity. His place in the world as a thinker, a teacher, a writer, was anchored to his library. To see it dismantled, discarded, and burned, I believe, turned off the lights in an unreachable part of him.

Over the years, Refaat and I had several discussions about his embrace of English literature instead of Arabic. Having been forced to leave my Arabic education at a young age, I would lament to him that it pained me to have never developed a sophisticated grasp of my poetically charged mother tongue. He agreed, mostly. But he found English more practical and pliable. More importantly, he wanted to master the language of the empire that oppressed him. Always thinking of Palestinian liberation, Refaat believed there was great value in speaking and writing to the people of empire to lay bare our humanity before them.

He believed people were essentially good; that if they could only see what was happening to us, they would stop supporting our colonizers; that if they could see the magnificent beauty of our souls, they might love us. He also wanted to ensure our lives would be recorded despite rampant efforts to erase our presence in the world.

Still, he was uncompromising in his convictions, and never withheld the sting of his tongue against injustice. His integrity and dignity, and the dignity and agency of Palestinians on the whole, were above all else.

As tributes now poured in for Refaat, all our grief mixing together, his poem for Shymaa recited over and over by so many people around the world, I was reminded of another indigenous leader who, like Refaat, was murdered because the light of her being shone too brightly.

Berta Cáceres of Honduras spent her life fighting for indigenous rights and for our deteriorating planet against extractive industries dismembering the earth, damming rivers, killing species, and stealing resources. When she died, the rallying cry of the thousands who loved and followed her was, “Berta no murió, se multiplicó!”

Likewise, Refaat no murió, se multiplicó!

Refaat did not die, he multiplied! ….. susan abulhawa, August 13, 2024