Ratify the R-Word—Bruce, Minneapolis, Revolution, and Us

Twenty four years ago I wrote an essay titled “Resurrect the R Word.” To many people back then revolution meant chaos, violence, and death. Disagree? Me too. But should we resurrect the R-Word? My answer back then was that we should and I have the same answer now. But now we should Resurrect and also Ratify the R-Word.

Talking about the U.S., where I live, a quarter century along history’s timeline Fascist thuggery, authoritarian, racist, and misogynist regimentation, war, and ecological dissolution threaten everything. Though the R-Word appears everywhere, what does it convey? Why should the R-Word re-enter our hearts and minds? Our Revolution? Not breakfast cereal revolution. Not cyber revolution. Our Political, Economic, Cultural and Social Revolution.

Seven and a half million people in the U.S. are unemployed. Forty million are poor. Forty seven million intermittently go hungry. Seven hundred and seventy five thousand have no material home. How many have no emotional, spiritual home? Even those who are not materially desperate largely lack personal say over their own lives. Trump is a disaster unfolding. But beneath Trump, indeed birthing and nourishing and elevating Trump, all manner of billionaire bosses rule here in what some like to call: USA, USA!

Employees sell their ability to produce and as a reward about 8 out of 10 of them suffer abject subordination, lurid lies, vile chicanery, and massive manipulation. All of it backed by force. Dignity is denied. Ambulance-chasing is a professional pastime. And with whatever means available, from bare minimum poor to vapidly rich, to fetishize and accumulate whatever commodities you can grab is a socially respected way of life.

To score high on the “I own” meter requires that you inherit or you accumulate and debauch without a care. However it is not capitalists’ genes, but the institutional byways that they traverse that exterminates their humane sentiments. The problem is not our genes. The problem is the institutions that channel our choices.

In our economies garbage rises. To profit, owners become social garbage. We all know it’s true. The idea that capitalists will freely forsake economic violence is delusional. We know that too. Capitalism doesn’t sincerely gift us fine schools, excellent health care, equitable incomes, solidarity among workers, people before profit, empathy over greed, self management beyond democracy, and an environment suitable for human habitation. To the extent we get any of that it is due to struggles undertaken against capitalism. Capitalism, of its own accord, exploits and alienates those who it does not elevate. Its pliers warp even those who it does elevate.

Humane pursuits and collective self-management require in place of capitalism collective ownership, equitable income and circumstances, balanced jobs that incorporate comparable access to information, responsibility, and skilled work for all, and decentralized participatory planning to replace rat race competition and top down coercion. Humane pursuits and collective self-management require classlessness.

It turns out that we endure economic violence but we want economic liberty. More, to go from economic violence to economic liberty is what economic revolution is all about. No old boss. No new boss. Instead new institutions. Ratify the R-Word. But is economics all we suffer? No, of course it isn’t. Consider what some call kinship.

Feminists teach that gender is social; women and men are each worthy; girls and boys, mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles, daters and datees are not anatomic roles but historically contingent outcomes. We are what we do. But we can do other than what nuclear families, contemporary sex roles, courting and parenting roles demand, and what fashion, Hollywood, religion, and bosses celebrate.

A sexual assault occurs in the U.S. nearly every minute. Upward of one out of five women suffer rape or attempted rape at least once in a lifetime. Eighty percent of all women suffer sexual assault or harassment at some time. Women earn just under eighty percent for comparable work as men. On the other hand, women do get considerable pay for modeling, acting, homemaking in mansions, and street-walking in Manhattan. Women do more housework than men and shoulder most responsibility for child-rearing. Women hold up half the sky and much more. But still women still suffer. U.S.A., U.S.A. Chant it proud?

U.S. teenage pregnancy is highest in the developed world while the multi-billion-dollar U.S. pornography industry evidences and elicits mind-staggering manufactured sexist perversion. Child-rearing and education relegate to young women who aren’t being trafficked the freedom to be “feminine” and obey, and relegate to young men who aren’t trafficking the freedom to be “manly” and rule. Society’s preponderant roles distort all genders, albeit quite differently. Billion dollar diets mutilate millions of human psyches and hundreds of thousands of human bodies. Tens of millions of men and women suffer indignity, brutality, and even death for their homosexual or trans lives, while the elderly suffer isolated poverty even as productive tasks they could do go undone.

Macho doesn’t presuppose male genes. It is not inscribed in DNA that men should objectify and batter women. Kinship violence stems not from genes gone bad, but from damaged families, from men fathering and women mothering, from pseudo-sexuality, reductive education, competitive courting, and sexist economics, politics, and culture.

To transcend gender violence we need sex-blind roles; support for single, coupled, and multi-parenting arrangements; plus easy access to high-quality daycare, flexible work hours, and parental-leave options. To produce gender peace we need freedom for children to develop views with their peers without excessive adult supervision. To produce gender liberation we need retirement guided by personal inclination and not age; liberated sexuality that respects all free choices and inclinations; and norms of courting, child-rearing, law, religion and work free from gender bias. In short, we need a transformation that replaces this country’s patriarchal misogyny with gender equality and sexual freedom. The R-Word needs ratification for kinship, too.

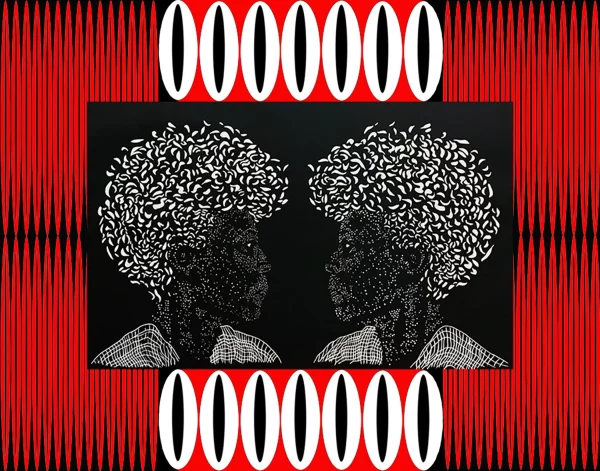

What about the ethnic, racial, and religious ways by which we understand ourselves and our place in society? Slavery, apartheid, separate but equal, racism, religious bigotry, ethnocentrism, and colonialism are all systems in which one community subordinates another or in which two communities wage endless conflict that deadens the cultural prospects, souls, and bodies of all concerned.

In the U.S., median family income, infant mortality, criminal prosecution, allocation of educational resources, and distorted and distorting mass media images all track race to ensure that nonwhite communities settle beneath white ones. These dynamics subjugate whole peoples. These dynamics deny whole peoples’ cultures and whole peoples’ potentials for developing and fulfilling themselves. They pervert ruler and ruled alike.

As a result, the U.S. is far from being a compendium of diverse free communities, each enabled to develop in harmony with others, each respecting and learning from answers that others offer, and each protecting the rights of all. To collapse all cultures into the norms of a dominant few via “integration” is no solution. The needed transformative change is revolution. The R-Word applies again.

U.S. politics features media-reinforced apathy, financial bribes and scams, police repression, regressive taxation, choices between candidate clones, massive corruption, aid to dictators abroad and at home, and wars. And of late it also includes a drive toward Fascism, which is Trump’s version of political revolution. Real participatory democracy will instead need to feature collective self-management including plebiscites, honest plentiful information, informed public debate, popular assemblies, maximum respectful accountability, reconstructed adjudication, and no possibility for accruing excessive political power.

To transition from spectator ruler-versus-ruled politics to participatory politics will therefore require new political aims and institutional means to debate them, refine them, dispute them, fight for them, and enact them, as well as to deal with violations. We the people need both information and power. Popular resistance campaigns to redress grievances can ease immediate suffering and nowadays forestall a slide to dictatorship, but they will not alone create new institutions able to propel informed participation. New polity will need revolution. The R-Word needs ratification here too.

Nations fight nations. Torture and war ravage human potential. Hunger afflicts billions. Chemical wastes infect us. Air pollution congests us. The seed-base depletes us and temperatures keep climbing toward ecological debacle. Forests diminish. Wastelands spread. People, animals, and plants drown, starve, and burn. Neither the world as a social system nor the world as an ecosphere can withstand much more, more, more. Without international equity plus new means for care-taking the earth, all will go to hell in a turbo-cart. In a dirty world, the R-Word is not a dirty word. Ratify it.

To feel embarrassed or afraid on hearing the R-Word makes liberated human history seem impossible. To equate revolution with blood-lust accepts that struggle for change can yield only minimal gains or, if we get too ambitious, worse than what we already have. To debate the wisdom of revolution reflects timidity about truth. We must no longer debate the wisdom of fundamental change as if humanity may after all be able to flourish or even just survive within the permanent dictates of capitalism, patriarchy, racism, and authoritarianism. Fundamental change is not only possible, it is essential. But a host of related issues do warrant continued and expanded debate.

For example, what new institutions would desirable economic, kinship, cultural, political, international, and ecological revolution create? We need to at least broadly know because we won’t get where we want to wind up if we have no clarity about at least the defining features of where we want to wind up. Do we now have that? Ratify the R-Word.

And how do we win immediate reforms while we strengthen our ability to fight for long-run aims? We need reforms to reduce pain now but also so the fight for them teaches and propels relevant lessons and so that winning them expands our confidence and develops our means to win more. That is R-Word logic.

And what kind of organization, ideology, and tactics do we need to reach our full goals? Since priority attention to economics, gender, culture, politics, international relations, and ecology yields contrasting socialist, feminist, nationalist, anarchist, anti-imperialist, and green agendas, including different views within each, how can a new movement retain the integrity, wisdom and autonomy of each of these orientations, correct whatever faults they may have, and simultaneously realize solidarity among them all? That is the R-Word’s call to action.

Debating these and related strategic questions while we raise consciousness, demonstrate, and organize to expand and enrich resistance isn’t “utopian.” It is the only comprehensive approach that can win immediate social change and also keep winning more change on the path to fulfilling R-Word mandates.

To win a new world, and even to significantly improve this one, we must know what we want. To journey from here to there we need to know where “there” is. What new institutions will establish real a participatory economy and in particular what steps can lead to those new institutions? What new institutions would establish a feminist kinship sphere, a culturally intercommunal community sphere, and a participatory political sphere? In each case, what steps can take us from what we have to what we need?

As we endure current horrors, it does not evidence maturity, pragmatism, or wisdom to dismiss revolutionary desire as strange, to see it as off base, or call it impossible. To dismiss what is in fact essential and desirable instead evidences ignorance, defeatism, or even lack of humanity. Don’t whisper the R-Word. Loudly ratify it.

But even as we do all that, we need to also remember that to win fulfilling freedom doesn’t require adopting arrogant postures that alienate potential allies. It doesn’t require dismissing that which isn’t yet where we are. Instead, to win fulfilling freedom requires sober yet comprehensive desire plus careful yet unrelenting forward movement. It requires that we listen, converse with, and respect people who disagree with us.

Liberalism’s half-way programs and temperate rhetoric, when unaccompanied by revolutionary insights, tend to strengthen the two greatest obstacles to justice in the U.S.: The widespread belief that you can’t beat City Hall and that even if you do beat the bastards, it won’t mean overly much because new bosses will be as bad as old ones. Isn’t it obvious that the left won’t arouse hope and deserve commitment until its morality, tone, and spirit transcend band-aid bureaucratic fixes even as it necessarily struggles to win those limited gains on the way to winning fundamental change in the longer run? Isn’t it obvious that we ultimately have to get to the institutional heart of the matter? Ratify the R-Word.

We can’t win what we won’t even name. We can’t orient today’s reforms to further tomorrow’s victories if we refuse to define what we want tomorrow’s victories to include. Blind strategy is no strategy at all. Resistance is good, but to undo lethargy and cynicism and attain liberation, we ultimately need to ratify the R-Word in our speaking, writing, thought, and action.

And so what does to ratify revolution mean right now, while ICE runs rampant, RFK Jr. sickens the country, Hegseth macho-man’s the media, and Trump twists the very fabric of reality to pursue his own maniacal brand of Fascism?

Just a few days ago I logged on to a collective call about resistance in Minneapolis—which city is now central to Trump’s violence and thus also to the resistance’s prospects. The online gathering was inspiring and hopeful in many respects and especially in its call for no work, no consuming, and no school in Minneapolis this Friday January 23rd (with the call now expanded to the whole of Minnesota, I believe), plus lots of accompanying activism against ICE and its abettor corporations and politicians conducted all week and especially on the 23rd. But beyond even the Minneapolis movement’s exemplary courage, commitment, and competency, to bring the R-Word back means that the movement in Minneapolis should work to begin to challenge not just ICE, the only focus during the call, but also tariffs, imperial bullying, police repression, racism, misogyny, rising prices, booming income and wealth differences and authoritarian governance. Resistance events and struggles everywhere need to begin to go from great on one issue to great on all issues. They need to appeal to and empower not mainly one constituency but all those with an interest in immediate and ultimately also in fundamental change. That will start to ratify the R-Word for this moment and also for the long march toward winning fulfilling freedom for all.

If young people stay home from school and consumers don’t consume and workers don’t work this Friday even just in Minneapolis much less throughout Minnesota it will be a huge step toward resurrecting and ratifying the R-Word there and toward inspiring other locales to do so elsewhere as well. Trump and Co. and their followers will hear that loud and clear. Our fear will decline. Their fear will rise.

Afterword: My last article, “Three Strategic Issues: What to Say or Write? What to Do? and Who to Do it With? Plus Taylor, Steph, and Caitlin…”, concluded with some entreaties to citizens with large audiences and ample media means to address them. It mentioned a number of such personalities by name and noted that while grass roots participants are the heart and soul of the now growing resistance, contributions from notable singers, actors, athletes, labor leaders, and more, and in high school and college classrooms from teachers and professors, can help create room for and inspire many more people to stand tall. And wouldn’t you know it, the man called The Boss with love and respect, not derision, last night previewed how to do it and today his words are all over. Look it up. At a New Jersey festival Bruce Springsteen introduced his song “The Promised Land” with these words:

“This next song is probably one of my greatest songs. And I don’t want to be out of water tonight, but I wrote this song as an ode to American possibility … both to the beautiful but flawed country that we are, and to the country that we could be. Now, right now, we are living through incredibly critical times. The United States, the ideals and the values for which it stood for the past 250 years, is being tested as it has never been in modern times. Those values and those ideals have never been as endangered as they are right now. So as we gather tonight in this beautiful display of love and care and thoughtfulness and community … if you believe in democracy, in liberty … if you believe that truth still matters, and that it’s worth speaking out, and it’s worth fighting for … if you believe in the power of the law and that no one stands above it … if you stand against heavily armed masked federal troops invading American cities, and using Gestapo tactics against our fellow citizens … if you believe you don’t deserve to be murdered for exercising your American right to protest … then send a message to this President. And as the Mayor of that city has said, ICE should get the fuck out of Minneapolis. So this one is for you, and the memory of the mother of three and American citizen Renee Good.”