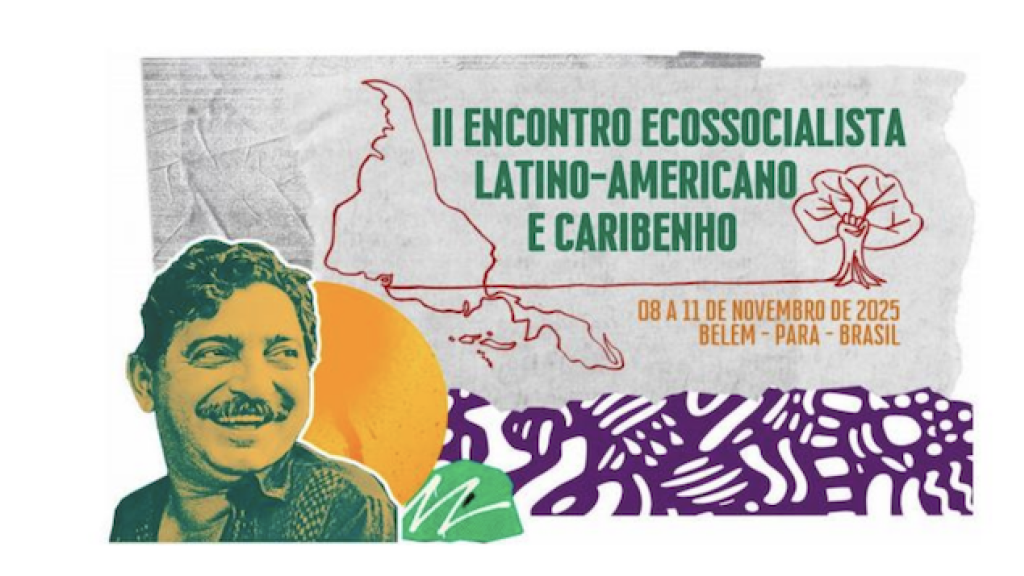

Statement from the Second Ecosocialist Meeting, held in Belém, Brazil, November 2025, with the participation of 99 organizations and more than 350 people, including a strong presence of organizations representing Indigenous peoples and Afro-descendants.

We don’t sell our land because it is like our mother. Our territory is our body. And we don’t sell our body. We don’t sell our mother. We wouldn’t sell it, because it is sacred.

And we start suffering pressures of invasion, pressure from mining, from agribusiness, which has expanded a lot, pressure from logging companies, which are deforesting our territories. And we have been resisting.

—Auricelia Arapiun, Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB).

We gather at moment of profound capitalist attacks on life, within the framework of the actions organized by the peoples in response to COP30. This meeting has allowed us, once again, to reaffirm that both the rise of the far right and the false solutions proposed by governments that call themselves progressive (yet do not hesitate to privatize the commons or facilitate attacks against peoples and leaders who face daily the consequences of the logic of infinite capital growth in their territories) push us to struggle for a world in which living systems are at the center of all our political constructions, and to forcefully reject any attempt at intimidation.

We have seen an example of what happens when, instead of strengthening the struggles of peoples who defend their territories at the risk of their own lives, the defenders of progressive neoliberalism place themselves at the service of capital and predatory extractivism. The political threats suffered by our Indigenous comrade Auricelia Arapiun during her intervention in our roundtable on the current conjuncture clearly reveal a sector acting within communities to sow fear and fragmentation. Yet we — just as Auricelia expressed in her response to the threat — neither remain silent nor compromise.

The offensive of the far right also manifests in our territories through attempts to violate our sovereignty, reproducing the same logics of subjugation and domination that existed in the past and persist today. Against this imperialist offensive, we, ecosocialists, defend a united front to resist and protect ourselves.

Ecosocialism, as a tool to build another world, has become necessary and urgent. The accelerating destruction of ecosystems’ capacity for reproduction and the neocolonial and imperialist character of the supposed alternatives proposed by the very system that created the current climate emergency represent a threat to our continuity as a species, leading us toward a point of no return.

Faced with this challenge, the only possible path is the coordinated organization of our struggles in order to surpass the capitalist system. The organized struggle of peoples, their resistance to systems of domination, and their progress in building other worlds founded on solidarity, complementarity, and reciprocity — respecting the knowledge and cosmovisions of different peoples as well as their legitimate rights to self-defense and self-determination — form the fundamental basis of our strategy.

These days of debate brought together representatives of peoples in struggle from different regions of Abya Yala [an Indigenous name for the Americas, meaning “Continent of life” —ed.] and other continents, who have raised their voices globally to denounce that capitalist and imperialist extractivisms are causing environmental and human destruction in many territories. It is necessary to strengthen the alliances among peoples in resistance in order to combat this destruction, while consolidating forms of life-production historically developed by the peoples and today threatened by the contamination and appropriation of water, land, and air by transnational corporations and governments.

The voices of Indigenous peoples were central in this gathering, identifying a shared context of colonialism, invasion, dispossession, extractivism, and false solutions — accompanied by policies of annihilation and genocide, which not only kill but also render these peoples invisible through criminalization and persecution. At this stage, we see the relationship between body and territory as a fabric where structural violence resides, but also the struggle for life. This struggle manifests in alternative forms of resistance, through the valorization and articulation of knowledge and cosmologies in which ancestry and nature are inseparable; and through self-defense, self-determination, community life, and the importance of hope and unity across territories.

These struggles for life also appear in ecofeminisms, highlighting the struggles of women and feminized bodies across different territories of Abya Yala as they confront the close and historical relationship between capitalism and the violence inflicted on the land, the territories, and women.

From the various forms of extractivism emerges a violence expressed through the contamination and destruction of land; the predation and theft of our commons; the fragmentation of cultural perspectives; and upon the feminized, impoverished, and racialized bodies of thousands of women of the Global South.

This analysis, in addition to identifying capitalism as the structural origin of all territorial violence, also proposes solutions capable of overcoming these contradictions — such as community water management, food autonomy, self-government, community justice, and a subversive conception of care. This vision of care arises from a structural critique of the neoliberalization of the care discourse, which continues to support the logic of capital. In contrast, we position ourselves in favor of collective and community care for radical transformation.

Eco-unionism is a fundamental component of the ecosocialist struggle. The fight for more and better working conditions, combined with the awareness that the exploitation of the working class and the dispossession of our commons serve the interests of capital and mutually reinforce each other, creates the conditions needed to mobilize and advance the structural causes of the oppressions we suffer under capitalism. In this sense, rejecting fracking in Colombia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and worldwide is a task we assume with responsibility to contribute to building free territories. We know that this will only be possible if trade unions articulate with social, popular, Indigenous, and peasant movements in each country, while maintaining their autonomy in defending territories, life, and its reproduction. Through internationalist solidarity, we commit to promoting spaces that denounce violations of labor, human, and natural rights.

From within this shared fabric, we unanimously cry out: Free Palestine, from the river to the sea; ceasefire in Gaza; and condemnation of the genocidal State of Israel for the massacre of the Palestinian people. A people who resist, who sow, who maintain the conviction to stand tall — and whom we embrace through internationalist solidarity, multiplying global actions of support such as BDS and the Flotilla, examples of grassroots resistance that the State of Israel considers threats.

We also demand that governments in the region break their relations with Israel, as in the case of agreements with Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, which has become an instrument of colonial domination. Water is a common good and, in Palestine, it is used as a political and economic weapon: Israel controls water sources, prevents Palestinians from drilling wells, collecting rainwater, or maintaining cisterns, thereby creating total dependence and a system of water apartheid. Palestine is a laboratory of domination whose techniques spread to other territories, and resistance and solidarity with the Palestinian people must be global. We, ecosocialists of the world, stand with and build active solidarity with the Palestinian people and their right to exist.

Days before the start of COP30, we once again observe that this space is incapable of responding to the needs of territories; on the contrary, it presents itself as a mechanism for the financialization of nature. This is why we reaffirm our denunciation and rejection of the payment of odious and illegitimate debts, and call for the dismantling of the international mechanisms that drive and legitimize them. These mechanisms mortgage our future in exchange for the delivery of strategic goods that capital needs for its unlimited reproduction. It is essential to dismantle the debt system, which subordinates and limits the capacity for a planned exit from the system.

We expect nothing from these spaces that propose projects such as carbon credits, which — just like TFFF — embrace the narrative that the problem is that the commons are not yet fully commodified and that there exists a “market failure” to overcome. We also denounce governments complicit in ecocidal projects, such as the Brazilian government which, only days before COP30 in Belém — an Amazonian territory — approved offshore oil exploitation at the mouth of the Amazon, and which, during COP30, approved the registration of 30 new pesticides.

We reaffirm agroecology as one of the paths that build our ecosocialist strategy. The production of agroecological food, rooted in peasant and Indigenous traditions, is not only an alternative to the dominant agro-food system — whose main actors are agribusiness and commodity production — but also a way to restore and rebuild ecosystems, and to break the alienation between countryside and city, making it fundamental in the fight against climate change. It is crucial to understand that agroecology cannot exist within green capitalism, as it involves, as a political practice, a structural transformation of current relations of production and life.

Recognizing that ecosocialism has for years worked to build manifestos and programs defining this strategy, we discussed the next steps and concluded that there can be no ecosocialism without free territories. We are certain that eco-territorial struggles and the construction of a livable world are the path we must follow, strengthening our initiatives in solidarity, and creating spaces where we can advance the construction of ecosocialism from and for the peoples.

To reach this goal, it is necessary to accumulate victories that show us the way. Carrying out mobilizations and campaigns among the different collectives engaged in building this ecosocialist project is essential to consolidate an integrated and internationalist process of coordinated resistance and shared strategy.

The continuation of this struggle and the construction of the ecosocialist program we need, along with the internationalization of the ecosocialist movement, are tasks we began ten years ago in these gatherings, and which were consolidated with the formation of the Internationalist Network of Ecosocialist Encounters in 2024, following the meeting in Buenos Aires.

Among new initiatives, we announce the Seventh Internationalist Ecosocialist Gathering, to be held in Belgium in May 2026; the International Ecosocialist Seminar, to be held in Brazil as part of the First International Anti-Fascist Conference; and the Third Latin American and Caribbean Ecosocialist Gathering, in 2027, in Colombia. We are convinced that these gatherings must transcend borders and generate common actions of struggle capable of striking simultaneously at the concentrated powers of capitalist extractivism in each territory where we are present.

However, Ecosocialist Gatherings alone are not enough to advance the construction of a program truly rooted in concrete struggles. For this reason, we propose the creation of joint actions and campaigns on Palestine, fossil fuels, mining, debt, and free trade agreements; the defense of water; the struggle against agribusiness; and forest restoration. We also propose mapping which companies are aligned with ecocidal projects in Latin American and Caribbean countries, in order to issue joint denunciations and communiqués. Additionally, we propose organizing territorial ecosocialist meetings prior to the one in Colombia, so that the debates reflect eco-territorialized formulations and proposals.

Finally, we want our space of construction to be living and diverse, capable of generating deep debates among its collectives, in order to think about and question our understanding of ecosocialism — reaffirming that ecosocialism is not a green-tinted socialism, but a proposal for a profound transformation of our relationships, both among ourselves and with nature. It is another way of doing politics, capable of building a new world, dignified and beautiful to live in, for human beings and all other living beings.