Resisting Autocracy

Image: "The World war at a glance; essential facts concerning the great conflict between democracy and autocracy" (1918). Public Domain

How do relatively functional democracies backslide into autocracy, and what can be done to reverse this?

This is the second of what I originally planned as a two-part series, which I now intend to split into three. In part one, I outlined a framework for measuring regimes based on their level of authoritarianism and their level of patronalism. I argued that the regime Donald Trump aspires to install in the US is one of patronal autocracy—an intermediary system between democracy and dictatorship, in which a corrupt “patron” and his informal network of cronies rule the country as an extension of their business interests. Another name for this regime type is a “mafia state.” I then explored some implications of this framework for our analysis of the emerging Trump regime.

In this part, I will:

- Outline a three-stage framework for understanding how aspiring autocrats go about transforming relatively functional liberal democracies into patronal autocracies.

- Examine two key defense mechanisms for resisting autocracy: the separation of political powers and the autonomy of civil society.

- Use these frameworks to assess the extent of US regression towards patronal autocratization at the level of both federal and state government, as well as that of civil society.

In the third part, I will:

- Outline a three-part taxonomy for resisting autocratic transformation, reversing democratic backsliding, and restoring and expanding democracy

- Discuss some implications of the above analysis for our tactics and strategy for the coming period.

Three stages of autocratic transformation

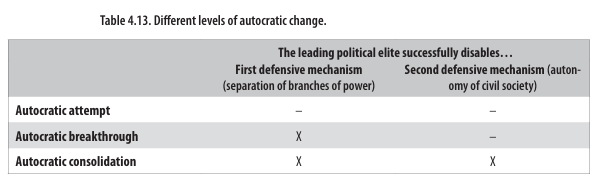

My analysis of stages of autocratization and democratization draws on a conceptual framework formalized by Hungarian political scientists Bálint Madlovics and Bálint Magyar. They argue that the transformation of democracy into patronal autocracy advances through three stages: autocratic attempt, autocratic breakthrough, and autocratic consolidation.

- In the first stage, autocratic attempt, an aspiring patronal autocrat who has been elected to office attempts to consolidate their unilateral control over all branches, levels, and levers of government. Within the executive branch, they attempt to change the rules on the appointment, promotion and replacement of civil servants, institutionalizing a nepotistic system of rewards and punishments. To weaken the judicial branch, they attempt to pack the courts, narrow the scope of judicial oversight, and appoint loyalists to prosecutorial and investigative state positions. To eliminate legislative checks, they attempt to change or ignore parliamentary procedures that obstruct the unilateral powers of the executive, and try to change election rules to disproportionately increase their party’s representation and deprive their opposition of a path to a majority. Simultaneously, the autocratic faction attempts to reduce or eliminate the vertical separation of powers between national, regional, and local governments by subordinating the latter to patronal vassalage and/or centralized political control.

- Autocracy advances to the second stage, autocratic breakthrough, if (and only if) the combination of the above attempts proves successful in effectively eliminating the separation of political powers. In this case, the autocratic faction achieves a constitutional coup—a seizure of power that functionally transforms the state into a new regime type, but maintains formal legal continuity with the ancien régime. Unlike a military coup d’état, this process does not overtly disrupt or defy the existing structures of governance. Instead it exploits loopholes, ambiguities, and technically licit powers to transform the system from within, gradually liquidating democracy and institutionalizing autocracy. This often involves repeated changes to the country’s constitution, achieved within the framework laid out by said constitution, but progressively rewriting the latter so as to fundamentally alter the “rules of the game.” Although a formal separation of powers may be (and generally is) maintained, this process functionally eliminates any real independence of the judiciary, the civil service, and the legislative branch, as well as that of local and regional government. This is the point, after an autocratic attempt, where we can speak of an autocratic breakthrough.

- The third and final stage, autocratic consolidation, happens if—and only if—autocratic forces are able to functionally disable what Magyar and Madlovics call the “second defense mechanism” of democracy: the autonomy of civil society. Even without formal political checks and balances, a well-established, heterogeneous, and independent civil society creates many social checks on patronal autocracy: independent media sources question the regime, independent NGOs function as watchdogs, an unbowed citizenry creates many groups that organize and advocate for their interests, and independent liberal economic elites fund all these efforts (as well as the political opposition). To consolidate control, the autocratic faction must neutralize these and other sources of independent initiative, subordinating or “vassalizing” civil society through a mixture of threats and incentives. Compliant organizations, institutions, and individuals can be rewarded with state funding, government contracts, beneficial regulations, and opportunities for individual advancement; defiant ones can be excluded from these opportunities, and also threatened with investigation, litigation, tax penalties, criminal charges, firing, or blacklisting. Note that none of these mechanisms formally forbid or outlaw independent initiative—this is what distinguishes patronal autocracy from outright dictatorship. Instead they make civic independence seem costly, and compliance (ostensibly) advantageous. If these mechanisms effectively neutralize or marginalize oppositional forces and voices in civil society, the regime change has advanced to the third stage: autocratic consolidation.

Two democratic defense mechanisms

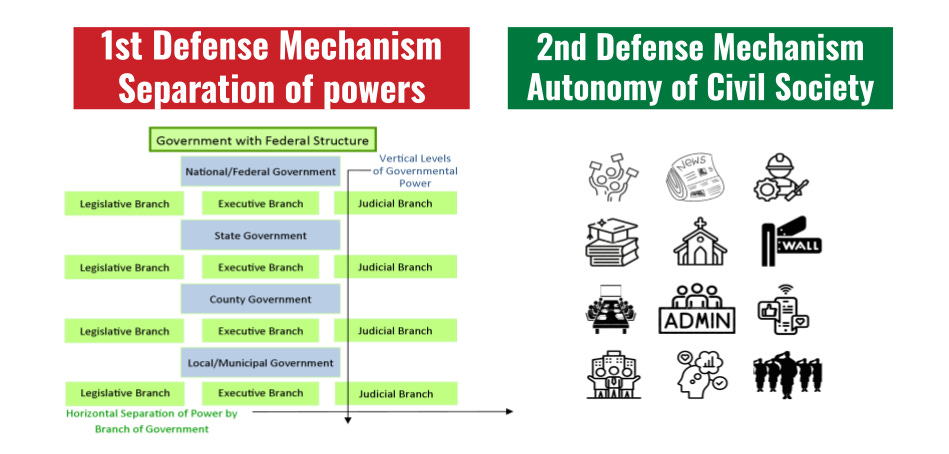

As the above analysis has already begun to surface, Magyar and Madlovics identify two key “democratic defense mechanisms” against the progressive transformation of liberal democracy into patronal democracy: the separation of political powers and the autonomy of civil society.

The first defense mechanism, the separation of powers, has both horizontal and vertical dimensions. Horizontally, this includes the separation of legislative, judicial, and executive powers—the branches of government. Additionally, this dimension involves the degree of operational autonomy exercised by the civil service and administrative apparatus—the levers of government. Vertically, this defense mechanism involves the separation of power between national, regional, and local government—the levels of government. The stronger the institutional boundaries between all these branches, levers, and levels of government, the more difficult it becomes for autocrats to secure a monopoly on political power.

The second defense mechanism, the autonomy of civil society, concerns the size, strength, diversity, and resiliency of civil society organizations. By “civil society” we mean all the different groups, organizations, and associations that exist within the geographic territory governed by a state, but that are formally and functionally independent of government. In their book Violence and Social Orders, economic historians Douglass North, John Joseph Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast suggest that most societies fall into one of two poles when it comes to civil society: either almost everyone can freely form and participate in independent organizations that compete against powerful economic and political interests (what they term an “open-access order”) or almost no one can (what they term a “limited-access order”). The degree of openness has important implications for the resilience of a society to authoritarianism. As they put it:

“A civil society reflects a wide range of organizations that are easily adapted to political purposes when a government threatens an open access order. Organizations from garden clubs and soccer leagues to multinational corporations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to interest groups and political parties all form pools of interest that can independently affect the political process.”

Drawing on this research, Magyar and Madlovics argue that the autonomy of civil society forms the second key defense mechanism against autocratization. While the separation of branches, levers, and levels of government provides internal checks on authoritarianism, it is the external independence of civil society that ensures the people’s right to have a say in how their life is governed. That is, the more independent civic organizations there are, the stronger they are, and the more people actively involved in those organizations, the more difficult it becomes for patronal autocrats to consolidate control.

Assessing US regression towards autocracy

Let’s sum up the argument so far. Autocratic change unfolds through three broad stages: an autocratic attempt, when an aspiring autocrat uses their elected office to try to consolidate power; an autocratic breakthrough, when they successfully gain control over the entire state apparatus, disabling the first democratic defense mechanism, the separation of powers; and autocratic consolidation, when the autocratic faction successfully disables the second democratic defense mechanism, the autonomy of civil society. These stages are gradual, and progression through them is not totally linear. (An autocrat with only partial control of the state apparatus can nevertheless make use of it to try and subjugate civil society.) But at a very general level, this schema is helpful for understanding the typical course that an autocratic coup attempt will take.

So how does Trump’s second term stack up according to these criteria, thus far?

On the one hand, this is Trump’s second autocratic coup attempt. As others have noted, both he and the forces around him are much better prepared this second time than the first. They have a clearer plan, have greater understanding about the institutions of government, and have achieved both much deeper and broader patronal vassalization over the Republican Party. There is a pattern of aspiring autocrats being ousted from office, only to mount a second attempt better prepared to consolidate power. In Hungary, for instance, Victor Orban was prime minister from 1998 to 2002, then lost reelection, and then came roaring back in 2010. He has been in office ever since. This should serve us as a cautionary warning.

At the same time, the US political system has many more checks and balances than the Hungarian one. Part of what enabled Orban’s sweep to power was his party’s securing of a two-thirds parliamentary majority that enabled him to freely amend the Hungarian constitution. The US bicameral legislature makes it more difficult to secure even bare legislative majorities, least of all the two-thirds majorities needed in order to pass Constitutional amendments—which then have to be ratified by three-quarters of the states. This points to another distinctive feature of the US: its federal structure, where a great many powers are vested in state government—certainly more so than in Hungary. In significant ways, the US is just as much 50 separate “republics” as it is one.

Additionally, the US has a much longer and richer tradition of civil society organizations than Hungary, with a much higher degree of autonomy from the state. Orban also came to power with much higher approval ratings than Trump, operated with far greater strategic savvy, and worked to reward his supporters with concrete economic populist incentives, which Trump does not appear poised to do. In light of these factors, Trump’s ability to consolidate autocracy seems much more doubtful. Indeed, this is why Magyar and Malovics explicitly argue that “America Won’t Become Hungary.”

The slow coup & the speed run

At the same time, there are two important factors that Magyar and Malovics do not appear to take into account, which complicate our ability to assess stages of autocratization in a US context. These two factors have different temporalities: one concerns the speed and scale at which Trump seems to be running the authoritarian playbook; the other a much slower and longer-term “march through the institutions.”

On the first front: if Trump is following the autocratic playbook laid out by Magyar and Malovics, he is speed-reading the large print edition. It took Orban the better part of a decade to consolidate autocracy in Hungary, and arguably even longer than that for Putin in Russia. Trump, Musk, and their minions seem to believe they have only a small “window” between now and the midterms to accomplish a comparable transformation—and are thus trying to race through the stages of autocratization in a fraction of that time. Such haste points to an underlying insecurity; if they had more confidence in the strength of their political and popular position, they could afford to move more slowly. But because this “accelerationist” strategy is untested, its effects are somewhat unpredictable.

In addition to its greater speed, the scope of such an autocratic coup attempt is many magnitudes larger when attempted by an (even declining) economic and global superpower like the United States than by a middling global power like Russia, or a negligible one like Hungary. Running the play bigger and faster does not actually make them any more likely to succeed at it. (If anything, I would argue the contrary.) But it does increase the risk that, in moving fast and breaking things, they will break something—the federal payment system, the global economy, world peace—so big that its consequences will propel us beyond the purview of any existing “playbook” whatsoever. Most of the potential ensuing scenarios do not seem to me to be favorable to MAGA’s ability to consolidate long-term autocratic control over the United States, but the point is that there is a non-negligible chance that we end up in such unprecedented system chaos that, in a sense, all bets are off.

On the second front: Trump’s autocratic coup attempt did not emerge from nowhere, but rather in relation to a much longer radical right-wing project to roll back social, political, and economic rights and “repeal the 20th century.” As others have argued, those efforts can be traced back at least as far as the 1968 Goldwater campaign, which witnessed the emergence of a concerted right-wing backlash against progress towards racial justice and inclusive democracy. (See, e.g. here, here, or here.) That backlash led the right to plot a long term “march through the institutions” that culminated in the right-wing takeover of the US Supreme Court, particularly after 2006, and the Republican takeover of many state legislatures during and after the 2010 Tea Party backlash. Those two factors then worked in tandem to advance a “slow-motion coup,” as the far-right Supreme Court stripped powers from the federal government and returned them to the states, while GOP-dominated states consolidated conservative autocracy at the state level.

That longer, quieter, slower-moving “constitutional coup” set the stage for our current high-speed run. There are many limits that the latter can and will run up against, and Magyar and Malovics’ framework helps us account for these. At that point, however, we revert to the temporality of the “slow-motion coup,” whose stages are more difficult to capture within a streamlined version of their otherwise helpful rubric. In the following sections, I will attempt to apply that rubric to a more detailed analysis of our two democratic defense mechanisms—the separation of governing powers and the autonomy of civil society. But as I do, I will also try to track places where Trump’s high-speed coup attempt rubs up against the slower-moving one.

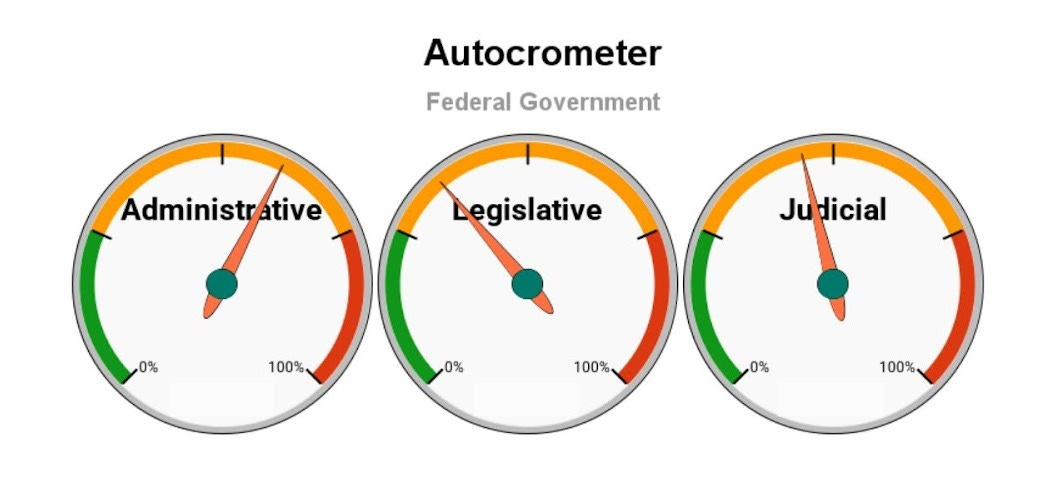

Defense Mechanism 1.1 – federal separation of powers

To visualize my analysis of stages of autocracy, I am going to bring back a reference from the first part of this series that I initially meant as something of a joke—an autocrometer. On the far left, in green, we can envision “zero” here as a flourishing liberal democratic system—not yet a post-capitalist socialist feminist utopia, but the very best version of, say, Scandinavian-style social democracy. On the far right, at 100%, we can envision full fascist dictatorship. In the middle, the yellow sections represent the various stages of autocratization: autocratic “attempt,” as green shades into yellow, then reaching autocratic “breakthrough” as it hits the middle marker, and approaching autocratic consolidation as the needle moves closer to the red/right. In the text I also indicate in which direction the “needle” is trending—deeper towards autocratic capture, or back towards democratization.

In a nutshell, it seems clear that the federal executive and administrative apparatus has experienced an autocratic breakthrough, which is rapidly trending towards autocratic consolidation. The judicial branch has experienced an autocratic attempt, but not yet a breakthrough; it is trending in that direction, but much more gradually. The legislative branch has experienced an autocratic attempt, but in contrast is trending back towards re-democratization.

Executive – autocratic breakthrough (trending autocratic)

The place where MAGA forces have made the fastest, deepest inroads towards autocratic capture is in their control over the administrative levers of the federal government. While reporting to the executive branch, the staff of federal departments and agencies have historically exercised a great deal of autonomy over their internal operations and external areas of administrative jurisdiction. Led by Musk’s DOGE team, MAGA forces have attempted a Blitzkrieg on virtually all bastions of administrative autonomy, shuttering entire departments, terrorizing others, and replacing career staff leadership with patronal loyalists. The consequences of these moves cannot be overstated; from taxation to criminal justice to foreign aid, many aspects of the federal administration are now deeply compromised.

At the same time, the federal administration is the component of the state apparatus with the fewest formal and constitutional protections from executive overreach; we should expect this to be the domain where fascist forces make the furthest inroads, the fastest. Even here, there have been many checks on autocraticization: resistance from organized labor, widespread litigation, court injunctions, media exposés, and public protest. In many areas, autocratic maneuvers have been blocked; where they have been successful, there is a real risk that MAGA’s victories will prove Pyrrhic, as the devastating consequences of dismantling popular programs start to be felt. As others have noted, we should not confuse their speed with their effectiveness—just because the clown car goes very fast does not mean it isn’t full of clowns.

Legislative – autocratic attempt (trending democratic)

In terms of the legislative branch, Trump’s patronal domination of his own party’s elected officials currently appears near-absolute; but on their own, the latter do not hold the majorities needed to pass substantive legislation. In a fully consolidated patronal autocracy, the legislative branch merely serves as a formal “rubber stamp” for decisions functionally made elsewhere. With a razor-thin House majority, and lacking the 60-vote supermajority needed to advance legislation in the Senate, Congressional Republicans can currently rubber-stamp cabinet and judicial appointments, and to a certain extent pass budget provisions through reconciliation, but can do very little else. This poses significant limits on the ability of autocratic forces to advance their agenda; the executive branch has great power over how (or if) to administer existing legislation and appropriations, but cannot create new laws and funding ex nihilo. Amidst deepening partisan legislative stalemate over the past decades, presidents have increasingly attempted to bypass such gridlock by “legislating” through executive order, contributing to the expanding power of the executive. But executive orders are inherently weaker and more limited than legislation, subject to reversal by future administrations, and vulnerable to rejection by the courts—to which we will turn in a minute.

Thus far we have seen virtually no independent initiative from within the ranks of the Republican House and Senate caucuses, even from the few remaining (relative) “moderates” like Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski. The reason for this is simple: Trump commands the near-unwavering loyalty of a majority of the Republican primary electorate, allowing him to credibly threaten to unseat representatives who defy him. Yet this points to a seeming paradox of authoritarian leaders: their power is just as (perhaps more) dependent on popular support as that of their democratic counterparts. Trump is posturing as if he had a popular mandate, but his stranglehold over the Republican primary electorate should not be conflated with broad support. At present, Trump regularly commands 60% or more of the Republican primary vote. But as Republican primary voters are only about 20% of the electorate, this proves unwavering loyalty from only perhaps 12% of the population. In terms of the broader electorate, Trump received a 49.8% plurality (but not a majority) of the popular vote—many of whom were voting against the last administration rather than enthusiastically for Trump—and his popularity is already declining. As it drops still further, we will see more willingness from some within his party to exert occasional autonomy.

Perhaps the quintessential move of aspiring autocratic regimes is to rewrite the rules governing elections in order to give themselves a larger and more effective legislative majority. Right-wing forces have been working to subvert democratic rule for decades, particularly by judicial fiat and through state-level gerrymandering and voter restrictions in states under Republican control. At the federal level, however, the GOP does not currently possess the majorities needed to enact electoral rule changes. At the time of writing, Trump is attempting to restrict the vote via executive order, but this will be contested in the courts and can be resisted by the states, which have great power over the governing of elections. Absent very rapid and widespread degradation of election integrity, which at this point still appears relatively unlikely, Democratic Congressional candidates will compete with electoral rules and maps in 2026 and 2028 that are about as fair as they are currently. (Which is to say, kinda sorta fair… ish.) Given the underlying electoral dynamics, this gives Democrats a pretty sure shot at regaining a House majority in 2026 (although a much more uphill battle for the Senate) and a decent shot at gaining or holding both chambers in 2028. For this reason, I list the legislative branch as “trending democratic.”

Judicial – autocratic attempt (trending autocratic)

On a judicial level, the federal courts have thus far been functioning as a fairly effective independent check on the Trump administration’s “fast-moving coup.” While there is no question that Trump is trying to skirt, sabotage, ignore, and overwhelm the courts, they have nonetheless been ruling against him frequently and consistently—the New York Times, which has been tracking lawsuits, has noted at least 53 rulings against Trump so far. According to the Institute for Policy Integrity, the first Trump administration lost almost 80% of court cases; at their current clip, the second one looks set to exceed that already high loss rate. And while Democratic-appointed judges have issued a majority of these rulings, Republican judges have also been fairly consistently ruling against the administration… at least those who were appointed by a president other than Trump.

We must be careful here to distinguish between the temporality of slow and fast-moving crises. Michael Podhorzer has convincingly argued that our deeper, slower-moving Constitutional crisis concerns the Federalist Society’s decades-long court-packing of the judiciary, whose rulings have paved the way for the situation we are now in. In that sense it is not just that the courts are currently “trending autocratic,” they have been doing so for many years; and while the rightwing 6-3 Supreme Court majority is the most visible component of this, Trump’s ability to push through hundreds of new federal judicial nominees over the next four years is perhaps an even greater risk to the long-term health and functionality of US democracy.

But in terms of the high-speed coup, the current federal judiciary seems prepared to resist judicial subordination to the executive branch, and to rule against many elements of Trump’s attempted subjugation of other branches and levels of government, and of civil society. Of the federal judiciary, 504 of the current sitting judges were appointed by Democratic presidents, 135 by one of the Bushes or Reagan, and 239 by Trump. We can expect reasonably independent rulings from non-Trump appointed judges, who currently make up over 75% of the federal judiciary. Although many cases will not make it as far as the Supreme Court, the latter will likely rule against the administration in many instances—despite the Roberts Court’s unrepresentative and hyper-partisan 6-3 Republican majority.

There is no question that the Roberts Court’s disastrous ruling on presidential immunity has given license to Trump’s most authoritarian impulses. But less noted has been that, while the Roberts Court has strengthened the personal power of the president, they have overall weakened the political and policy-setting power of the executive branch. This is consistent with the longstanding conservative-libertarian orientation of the Federalist Society, which has overall sought to diminish the powers and purview of the federal government in favor of so-called “states’ rights” and the unfettered power of business. That ideological consensus is now splitting as some right-wing jurists contemplate using the right’s control of federal political power to advance its cultural agenda, but we should not underestimate the commitment of many right-wing juridical ideologues to the principles of separation of powers and limited government. Such judges will likely not oppose the deconstruction of federal administrative autonomy, which is consistent with their right-libertarian ideology, but will oppose attempted subjugation of the powers of the legislative branch and of state government. For this and other reasons, the balance of power at the state level will be particularly important.

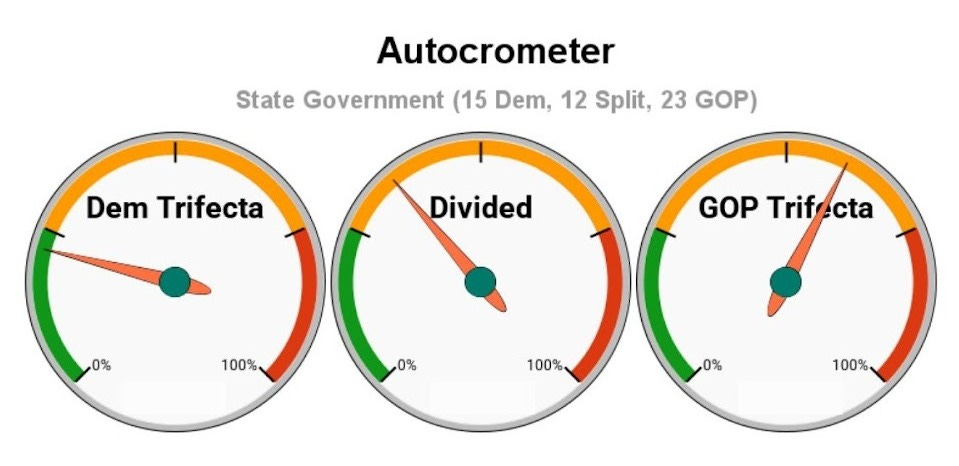

Defense Mechanism 1.2 – state-level powers

Rather than concentrating power at the national level, the US “federated” system divides power between the national government and the states. Not only does this give the states significant internal autonomy over the governing of affairs within their territory; states also exert substantial “upward” influence over the federal government. This creates a reciprocal relationship in which the balance of power at the state level can transform that at the national level, and vice versa.

The reciprocal relation of state and federal power can perhaps best be understood by examining the “state-based strategy” that the right has used to consolidate political power. When populist backlash against Obama propelled Republicans to state-level government in 2010—critically, a redistricting year—the right undemocratically gerrymandered districts, passed restrictive new voter ID requirements, and otherwise rigged the rules so as to increase their chances of maintaining legislative (super)majorities even in situations where they won a minority of the vote, thus consolidating semi-permanent autocratic rule. A good rough measure of parties’ political power at the state level is “state government trifectas,” where one party controls the governorship and both chambers of the state legislature. By November 2016, the right’s autocratic measures had contributed to the GOP securing trifecta control over 26 states, compared to only six trifectas held by Democrats. In many ways, it was this state-based strategy that laid the groundwork for the right to begin to plan the takeover at the federal level that has culminated in the second election of Donald Trump.

The good news is that, since 2016, Democrats have come a long way in closing that gap. Today, GOP state trifectas have declined from 26 to 23, while Democratic state trifectas have risen to 15, with 12 states under divided rule. As Michael Podhorzer has noted, Americans increasingly live in not one but two different nations, as Democratic-controlled states have moved to expand political, social, and economic rights while Republican-dominated ones have further restricted them. The states under Democratic control (and, to a lesser extent, divided control) provide ample opportunities to check the autocratic ambitions of the Trump administration. Indeed, the Democratic states’ attorneys general have thus far proved one of the most well-prepared and consistent bastions of resistance to Trump’s authoritarianism.

A full analysis of US democratic backsliding would thus have to take into account the level of regression towards and resilience against autocracy at a state-by-state level. Very broadly, we could say that, of the 23 states under trifecta Republican control, most have experienced some level of autocratic attempt, and in many of them the right has achieved a state-level autocratic breakthrough, rigging the rules of the game so as to ensure semi-permanent rule despite the continuation of nominally competitive elections. In a handful of these states, such as Florida, authoritarianism has further progressed towards something like autocratic consolidation, in which the autonomy of civil society has been deeply compromised. (See, for instance, the aggressive takeover of Florida liberal arts colleges.) In Democratic-controlled states, in contrast, democratic processes have been maintained, and in many cases expanded, and in divided states, autocratic attempts have thus far also largely been repulsed.

Because the states possess a great deal of power over the administration and regulation of elections, the state-level balance of power also impacts the level of fairness and competitiveness of US Congressional and presidential races. Of the seven battleground states most likely to determine the 2028 presidential election, Democrats currently control the main elected positions responsible for electoral administration in six of them (although in North Carolina, Republican state legislators have launched a power grab to wrest these powers from the Democratic governor and attorney general). Meanwhile, the Democratic Association of Secretaries of State has announced a $40 million electoral plan to defend those key seats in 2026, while targeting the seventh (Georgia) and expanding their efforts to other contestable states. Thus, although the right-wing’s autocratic capture of many state governments has contributed to the erosion of electoral fairness at both the state and federal electoral level, the current balance of state-level power is overall favorable to protecting the (relative) fairness of the 2026 and 2028 federal elections.

Defense Mechanism 2.0 – civil society

If my analysis of the US’s “first defense mechanism” already proved unwieldy, a comprehensive analysis of its second dimension—civil society—exceeds what I can accomplish in a relatively short article. Instead, I will briefly review some existing civil society indexes and then add a few provisional points of my own.

Indexing Civil Society

In an ideal world, I could simply point to existing analyses to measure the US’s level of civil societal resilience. And indeed, plenty of datasets attempt to measure such a thing. The problem is that many of these efforts have historically been directly or indirectly backed by the US and/or used to advance its interests. That means that many rankings of US civil society are apt to be colored by bias—when they even bother to include the US in their rankings at all. Indeed, in a painful irony, one of the most commonly cited such frameworks, the “Civil Society Organizations Sustainability Index,” was managed by USAID, which has now been shuttered in the very kind of repressive maneuver that the now-compromised index set out to catalogue. (Who, one might ask, analyzes the global civil society analysts?) Still, with all their problems, such indices provide some helpful quick reference points—particularly when contrasting their rankings of the US with those of NATO allies and other regimes historically “friendly” to the US, where the analysis is less likely to be colored by bias than when ranking, say, China or Cuba. To that end, let’s briefly review two such indices.

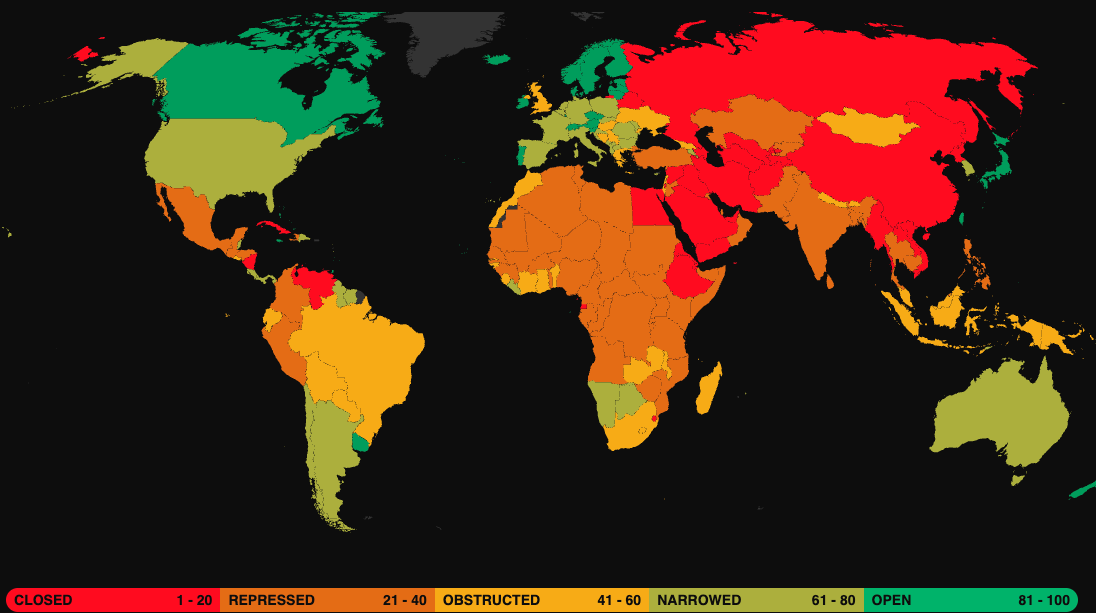

One such index, the CIVICUS monitor, currently rates the US as a 62 on its “civil space” ranking. While lower than truly open civil societies like Canada (82) or Sweden (87), this still places the US above the vast majority of nations assessed. Interestingly, CIVICUS places many western European countries at a level comparable to the US—France ranks only a few points higher (67) and the United Kingdom a few points below (60). For comparison with more autocratic regimes, CIVICUS scores Hungary at 46, Turkey at 24, and Russia at 14. This may provide one rough indicator of where US civil society falls on our “autocrometer.”

Another such assessment comes from Freedom House’s “freedom in the world” ranking, a combination of its “civil liberties” and “political rights” scores. It currently ranks the US as 33/40 on political rights and 50/60 on civil liberties, for a total of 83/100. (Though as Freedom House is mostly funded by the US State Department, it will be interesting to see how those rankings change… or if they last!) More helpful than looking at the topline number is drilling down into the description and ranking of various sub-components of US civil society. For those interested, I particularly encourage looking at their answers to the questions: “Are there free and independent media?” “Is there academic freedom, and is the educational system free from extensive political indoctrination?” and “Is there freedom for trade unions and similar professional or labor organizations?”

The Civil Societal Paradox

Here’s the paradox that I am struggling with. Let’s take some of the key institutional sectors of civil society: the media, universities, NGOs, labor unions, churches, civic associations, and grassroots membership groups. With the very notable exception of organized labor (to which I will return) the US is teeming with such organizations. Taken collectively, our civil society is older, richer, more well-established, and more manifold than almost anywhere else in the world. This is something that already stood out to the trenchant French writer Alexis de Tocqueville when he visited the fledgling United States in the 1830s. As he wrote then:

“Americans of all ages, conditions and all dispositions constantly unite together. … To hold fetes, found seminaries, build inns, construct churches, distribute books, dispatch missionaries to the antipodes. They establish hospitals, prisons, schools by the same method. Finally, if they wish to highlight a truth or develop an opinion by the encouragement of a great example, they form an association.”

This proliferation of civil societal organization astonished Tocqueville. Nothing equivalent then existed in a still quasi-feudal Europe, whose linkages were not those of voluntary association but of “bonds” (of kinship, fealty, guild, estate, etc.) that we might indeed qualify as “patronal.” Tocqueville initially feared that, in the absence of such “fixed” (involuntary) social relationships, America would fragment into a mass of isolated individuals, each pursuing their own solipsistic interests. He further feared that such social fragmentation, in turn, would leave an atomized American society vulnerable to the emergence of a paternalistic, despotic central government worse than even the most despotic of European monarchs. It was precisely the richness of American civil society that alleviated this concern for him. In other words, he agreed that civil society was a (perhaps the) key defense mechanism against authoritarianism.

Today, we have more civil society organizations than ever—some 1.97 million non-profits, according to the IRS, and that’s not counting the millions more (little leagues, neighborhood watches, etc) too small to register. And yet, despite that, we have witnessed the emergence of exactly the kind of “democratic despotism” that Tocqueville feared. Why?

The Civic Wizard of Oz

Here’s the answer I fear. The past decades have seen an explosion of civil society, with many individual organizations growing in size and complexity amidst a proliferation and diversification of the total number of organizations in aggregate. However, this growth has coincided with an overall decrease in the number and strength of member-led, participatory organizations; an increase in the number of top-down (staff-, board-, owner-, founder- or investor-driven) organizations; and a tendential process of verticalizing and hierarchizing power within “hybrid” organizations that fall somewhere in between those two extremes. In this sense it has seen an “explosion” of civil society in a second meaning of the term, of hollowing-out. The richness of our civil society is in some ways chimeric: behind the powerful facade of voluntary association and organization, there is very little actual associating or organizing going on. It’s a civic wizard of Oz.

In Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam famously traced the decline of participatory civic engagement. In the mid-twentieth century, most Americans belonged to and actively participated in one or more voluntary associations: rotary clubs, bowling leagues, cultural groups. Today, few do. Instead, as Theda Skocpol explored in Diminished Democracy, such participatory organizations have been replaced by staff-led advocacy groups. Where voluntary associations got most of their energy from their membership (perhaps supported by paid staff) today’s non-profit sector is mostly driven by paid staff (who perhaps occasionally wheel out a token member or two). Likewise, these organization’s financial models have shifted away from grassroots donations and membership dues towards wealthy donors and foundation funding— and, increasingly, government, as the neoliberal state has outsourced key formerly public sector roles to the non-profit sector. Today, almost 70% of nonprofits receive government grants, and 29% of total nonprofit revenue comes from the government sector. (See this recent article, which my analysis in this section draws on.)

Perhaps the most severe drop in participatory organizations has been the decline of organized labor. In the 1950s, some 35% of American workers belonged to labor unions. Today, only 9.9% do—and only 5.9% of workers in the private sector. This is in large part due to a systematic assault by the corporate elite against worker power, which was catalyzed by Reagan’s firing of 11,000 striking air traffic controllers, and which Trump, Musk, and DOGE appear to be trying to finish up with their nuclear assault on the federal labor force.

Meanwhile, many organizations which have retained the robust involvement of many people have nevertheless seen a usurpation of decision-making processes away from mass participation towards centralization and hierarchy. Take the recent, disastrous decision of Columbia University to concede to the demands of the Trump administration. I have no doubt that a majority of university students, staff and alumni oppose this capitulation, as did the faculty—who used to be the ones to make decisions about university policy. So who actually runs Columbia University? A small group of trustees, none of them academics, most of them wealthy entrepreneurs in the finance and technology sectors.

This shift away from faculty self-governance towards control by a wealthy, unaccountable elite is not unique to Columbia; it has played out across all of higher education, and resonates with parallel processes unfolding across many sectors of civil society. In other words, the undemocratic, anti-labor, patronal autocratic capture that Trump is now attempting to carry out at the level of the federal government has been preceded by a decades-long process of patronal capture that has played out within and across many institutions of American civil life. It is the decline of participatory, democratic processes in our civic institutions that has helped to pave the way for the assault on the broader political institutions of representative democracy.

And here’s the thing: even hierarchical, hollowed-out institutions can play a role in the resistance against authoritarianism. Our civil society institutions remain manifold, and Trump will have to subordinate an extraordinarily large number of relatively autonomous bastions of power if he is to bring them to heel. In the immediate temporality of our fast-moving coup, I would give our civic society a decent ranking in terms of resiliency. It is the longer-term, slower erosion that we may need to worry most about.

The good news is, most of us are connected to organizations we can revitalize, democratize and organize: universities, churches, unions, independent political organizations, non-profits, neighborhood groups. And just as in the first Trump administration, thousands of new grassroots resistance-focused groupings are again springing up. In the short term, organizing within all these spaces to refuse, resist and contest Trump’s agenda will be crucial to repelling authoritarianism; in the longer term, strengthening and democratizing them will be vital to laying the groundwork for the world we need to build.

But that will be the subject of the last section of my three-part post. Stay tuned.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers. Donate

No comments:

Post a Comment