The Age of Acrimony: How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865–1915, by Jon Grinspan, Bloomsbury, 2021

Fred Mazelis

During this same period, lynching was rapidly increasing in the South, and poll taxes and other methods effectively disenfranchised the freed slaves and their children, but also many poor whites. In the Northern states the techniques were different, but the results were somewhat similar. As Grinspan describes it in his book, as well as in an article in the Washington Post several months ago, “‘reformers’ could not simply disenfranchise their lower classes. But perhaps, they schemed, they might make participation unappealing enough to discourage turnout.” Among other techniques, “states passed new registration laws and literacy requirements, moved polling places into unfriendly neighborhoods, and most employers stopped letting their workers take time off to vote.”

This is part of the explosive growth of inequality, a Second Gilded Age even more extreme than the first. This level of inequality is not compatible with rights that have been won or tolerated in the past. This is the significance of the emergence of Trump, the ongoing transformation of the Republicans into a fascist party, and the complicity and bankruptcy of the Democrats in the face of the fascist danger.

This deepening onslaught on the working class is provoking a response, visible today in such developments as the growing strike wave as well as the mass protests against police killings. A period of revolutionary struggle has opened up, in the US and internationally.

The defense of the right to vote is bound up with the struggle for the political independence of the working class. It must answer the capitalist state’s suppression of democracy with genuine workers’ democracy and a workers’ state. The fight for socialism, smashing the capitalist class’s stranglehold on economic life, is the only answer to the COVID-19 pandemic and the threat of war and fascist dictatorship.

Fred Mazelis

WSWS.ORG

17 November 2021

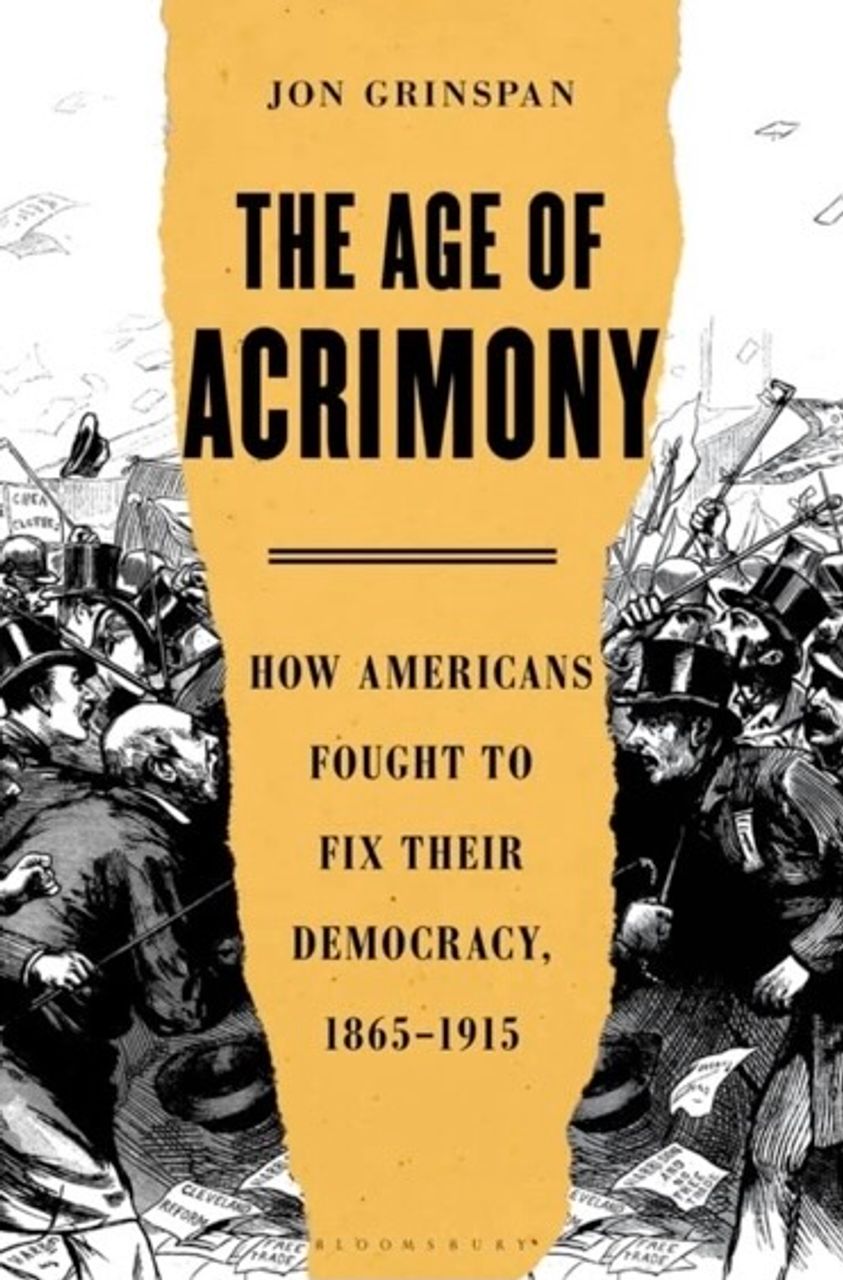

The subtitle of Jon Grinspan’s recently published book, The Age of Acrimony, is somewhat misleading. It reads, “How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865–1915.”

Americans were and are divided into mutually antagonistic classes, however. A more accurate description would be, at least in part, “How US capitalism established the modern two-party system of bourgeois rule.” As the author shows, this included the effective disenfranchisement of the poorest and most exploited sections of the working class—the restriction, not the “fixing,” of democracy.

Grinspan, the curator of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, has written an interesting and informative book, even if limited both in its scope and by its theoretical outlook. He deals with the half-century following the US Civil War.

17 November 2021

The subtitle of Jon Grinspan’s recently published book, The Age of Acrimony, is somewhat misleading. It reads, “How Americans Fought to Fix Their Democracy, 1865–1915.”

Americans were and are divided into mutually antagonistic classes, however. A more accurate description would be, at least in part, “How US capitalism established the modern two-party system of bourgeois rule.” As the author shows, this included the effective disenfranchisement of the poorest and most exploited sections of the working class—the restriction, not the “fixing,” of democracy.

Grinspan, the curator of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, has written an interesting and informative book, even if limited both in its scope and by its theoretical outlook. He deals with the half-century following the US Civil War.

Book cover of "Age of Acrimony"

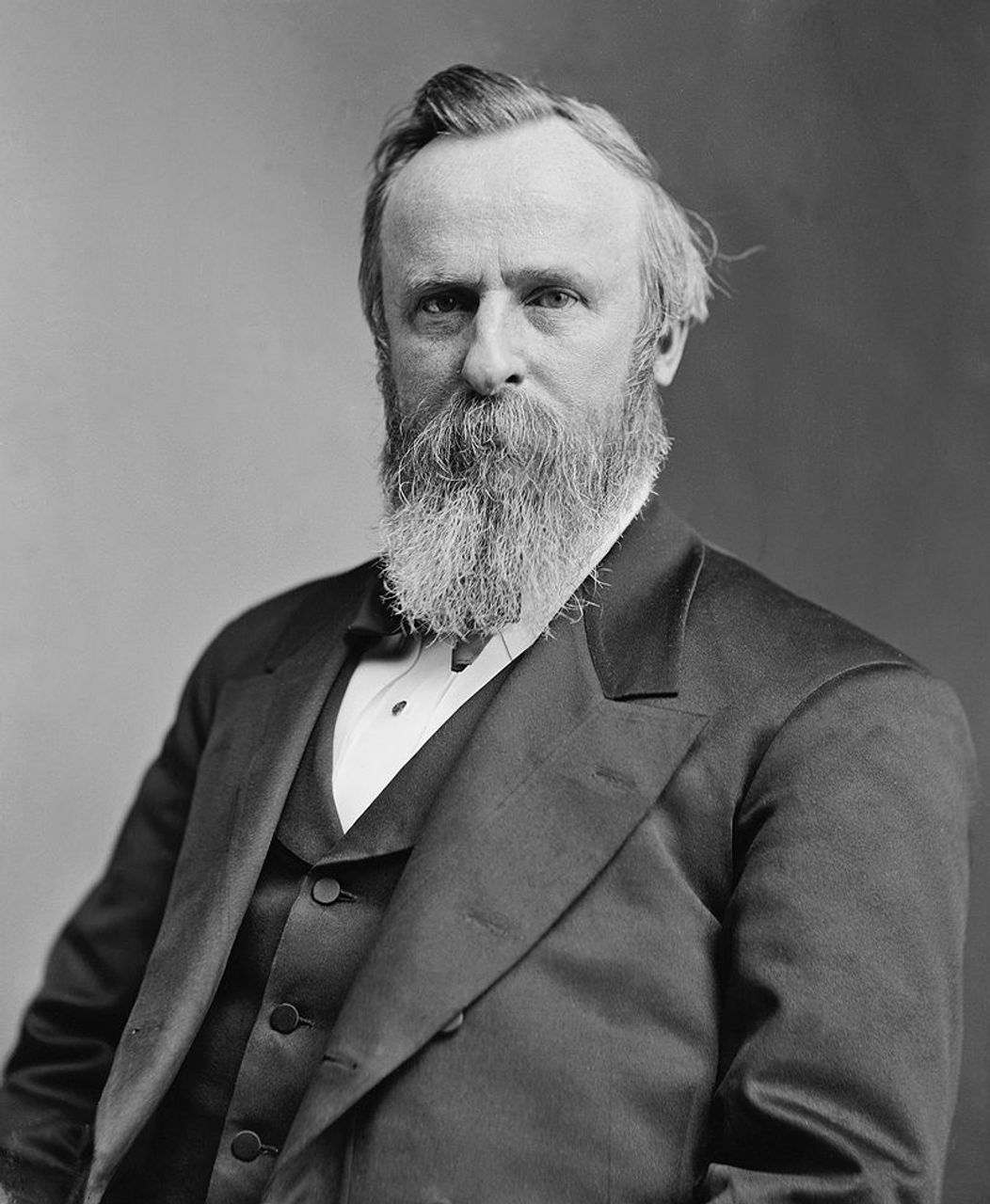

The Second American Revolution ended chattel slavery, and the Reconstruction Period was characterized by significant reforms, including the extension of the right to vote to several million former slaves. It soon gave way to counterrevolution, however. The Republican Party abandoned Reconstruction. The Compromise of 1877, which installed Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House—after a bitterly disputed election in which Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote—in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the former Confederacy, was a fundamental turning point.

The shift reflected the dominant interests of the ascendant bourgeoisie. Having established its supremacy through the Civil War, it was more than willing to make a deal with its former foes. Slavery did not return, but it was supplanted by the Jim Crow system of segregation, terror and second-class citizenship for the African-American population in the South, while the North led the way in the massive industrialization of the country.

The Second American Revolution ended chattel slavery, and the Reconstruction Period was characterized by significant reforms, including the extension of the right to vote to several million former slaves. It soon gave way to counterrevolution, however. The Republican Party abandoned Reconstruction. The Compromise of 1877, which installed Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in the White House—after a bitterly disputed election in which Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote—in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the former Confederacy, was a fundamental turning point.

The shift reflected the dominant interests of the ascendant bourgeoisie. Having established its supremacy through the Civil War, it was more than willing to make a deal with its former foes. Slavery did not return, but it was supplanted by the Jim Crow system of segregation, terror and second-class citizenship for the African-American population in the South, while the North led the way in the massive industrialization of the country.

President Rutherford B. Hayes

Republicans continued to “wave the bloody shirt” well into the 1880s and even later, using memories of the Civil War to appeal to a broader base that remembered the fight against slavery. The Democrats rebuilt their electoral fortunes, based both upon the former slaveholders and their supporters in the South, and the growing patronage machines in the northern cities, resting on the growth of industry and the working class, including several million immigrants.

Election campaigns during the 1870s were a time of torchlight parades and mass activity. The large voter turnouts included newly enfranchised African-Americans—women’s suffrage would not arrive for almost another half-century.

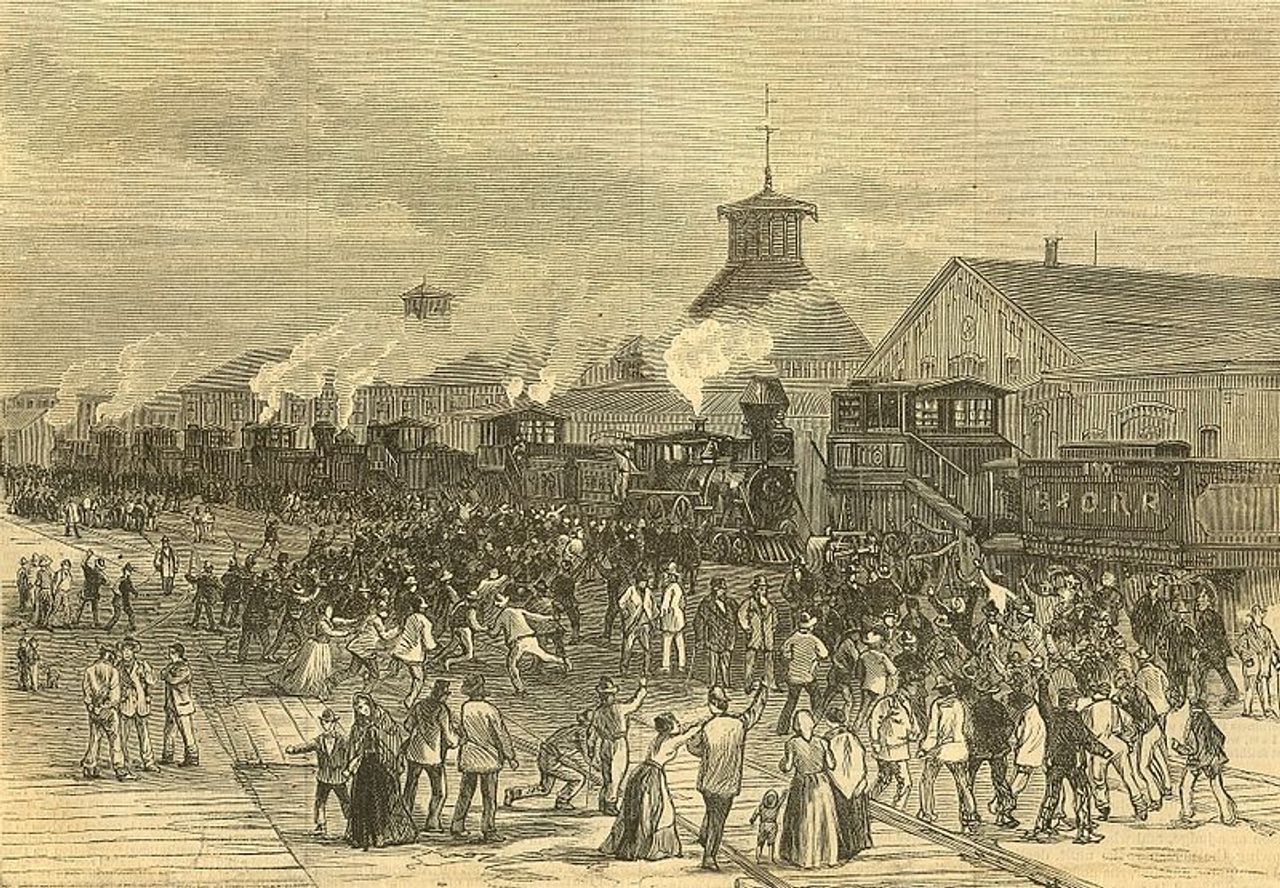

Party affiliation was emphasized, but political issues receded into the background in the years after Reconstruction. This was a time when the class struggle erupted in such battles as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Partisanship was a way to divert attention from the class issues and the need for the political independence of the working class. Voters were instead divided along tribal lines, into the two big parties of big business. Although much has changed in the past 150 years, similar techniques are used today.

Grinspan writes about the fears of the ruling class during this period:

Racist pogroms tore apart southern cities, and ethnic and class tensions caused riots in Manhattan in 1870, 1871 and 1874. Across the Atlantic, Paris exploded in 1871, as the revolutionary Paris Commune seized control of the city, before being brutally put down by the French state, which massacred twenty thousand. Americans frightened themselves with predictions of their own coming commune… Then, in the spring of 1877, one hundred thousand railroad workers struck around the United States, protesting the wage cuts that had shrunk their earnings by nearly one-quarter since 1873. The movement was crushed by state militias and federal troops, killing about one hundred strikers. Fearing communes abroad and strikers at home, the wealthy began to talk about the coming fall of civilization, pointing to various barbarians at various gates.

The reference to the Paris Commune is particularly significant, reflecting the international character of the class struggle as the system of capitalist production grew. Both Democrats and Republicans began to rely on growing middle-class layers as a force for political stability, a buffer and a means of silencing a revolutionary movement within the working class.

Republicans continued to “wave the bloody shirt” well into the 1880s and even later, using memories of the Civil War to appeal to a broader base that remembered the fight against slavery. The Democrats rebuilt their electoral fortunes, based both upon the former slaveholders and their supporters in the South, and the growing patronage machines in the northern cities, resting on the growth of industry and the working class, including several million immigrants.

Election campaigns during the 1870s were a time of torchlight parades and mass activity. The large voter turnouts included newly enfranchised African-Americans—women’s suffrage would not arrive for almost another half-century.

Party affiliation was emphasized, but political issues receded into the background in the years after Reconstruction. This was a time when the class struggle erupted in such battles as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. Partisanship was a way to divert attention from the class issues and the need for the political independence of the working class. Voters were instead divided along tribal lines, into the two big parties of big business. Although much has changed in the past 150 years, similar techniques are used today.

Grinspan writes about the fears of the ruling class during this period:

Racist pogroms tore apart southern cities, and ethnic and class tensions caused riots in Manhattan in 1870, 1871 and 1874. Across the Atlantic, Paris exploded in 1871, as the revolutionary Paris Commune seized control of the city, before being brutally put down by the French state, which massacred twenty thousand. Americans frightened themselves with predictions of their own coming commune… Then, in the spring of 1877, one hundred thousand railroad workers struck around the United States, protesting the wage cuts that had shrunk their earnings by nearly one-quarter since 1873. The movement was crushed by state militias and federal troops, killing about one hundred strikers. Fearing communes abroad and strikers at home, the wealthy began to talk about the coming fall of civilization, pointing to various barbarians at various gates.

The reference to the Paris Commune is particularly significant, reflecting the international character of the class struggle as the system of capitalist production grew. Both Democrats and Republicans began to rely on growing middle-class layers as a force for political stability, a buffer and a means of silencing a revolutionary movement within the working class.

Blockade of engines at Martinsburg, West Virginia during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The subsequent decades continued to be ones of explosive class struggle as well as political instability. The “irrepressible conflict” that led to the Civil War reemerged in another form, this time the conflict between expanding capitalism and the powerful working class that grew alongside it.

Between 1865 and 1901, three US presidents (Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley) were assassinated. Grinspan briefly mentions the infamous Haymarket frame-up of Chicago anarchists in 1886. He writes:

Cities were training militias, passing vagrancy laws, and restricting public rallies with permitting requirements. And across the nation, strikers were met with truncheons and rifles. The National Guard was called out 328 times between 1886 and 1895. In 1894, an Ohioan named Jacob Coxey led a ragtag assembly of unemployed protesters in the first march on Washington. ‘Coxey’s army,’ as they were called, were beaten and arrested for trampling on the grass around Capitol Hill. To the well-to-do of the 1890s, public gatherings seemed newly ominous.

The Civil War marked the completion of the bourgeois revolution in the United States. The abolition of slavery cleared the path for the system of “free labor” across the country. The Gilded Age, in which Rockefeller, Morgan, Vanderbilt and Carnegie became household names, was marked by extremes of inequality never previously seen. It also saw explosive class struggles. The Great Railroad Strike was followed by the Homestead and Pullman strikes in 1892 and 1894, respectively, brutally suppressed by the state.

This was the context within which the ruling class began to move away from the kind of “mass democracy” it had earlier utilized, in favor of “respectability” and “civility” in politics. Mass political involvement was deemed too dangerous at a time of mass struggle.

The subsequent decades continued to be ones of explosive class struggle as well as political instability. The “irrepressible conflict” that led to the Civil War reemerged in another form, this time the conflict between expanding capitalism and the powerful working class that grew alongside it.

Between 1865 and 1901, three US presidents (Lincoln, Garfield and McKinley) were assassinated. Grinspan briefly mentions the infamous Haymarket frame-up of Chicago anarchists in 1886. He writes:

Cities were training militias, passing vagrancy laws, and restricting public rallies with permitting requirements. And across the nation, strikers were met with truncheons and rifles. The National Guard was called out 328 times between 1886 and 1895. In 1894, an Ohioan named Jacob Coxey led a ragtag assembly of unemployed protesters in the first march on Washington. ‘Coxey’s army,’ as they were called, were beaten and arrested for trampling on the grass around Capitol Hill. To the well-to-do of the 1890s, public gatherings seemed newly ominous.

The Civil War marked the completion of the bourgeois revolution in the United States. The abolition of slavery cleared the path for the system of “free labor” across the country. The Gilded Age, in which Rockefeller, Morgan, Vanderbilt and Carnegie became household names, was marked by extremes of inequality never previously seen. It also saw explosive class struggles. The Great Railroad Strike was followed by the Homestead and Pullman strikes in 1892 and 1894, respectively, brutally suppressed by the state.

This was the context within which the ruling class began to move away from the kind of “mass democracy” it had earlier utilized, in favor of “respectability” and “civility” in politics. Mass political involvement was deemed too dangerous at a time of mass struggle.

During this same period, lynching was rapidly increasing in the South, and poll taxes and other methods effectively disenfranchised the freed slaves and their children, but also many poor whites. In the Northern states the techniques were different, but the results were somewhat similar. As Grinspan describes it in his book, as well as in an article in the Washington Post several months ago, “‘reformers’ could not simply disenfranchise their lower classes. But perhaps, they schemed, they might make participation unappealing enough to discourage turnout.” Among other techniques, “states passed new registration laws and literacy requirements, moved polling places into unfriendly neighborhoods, and most employers stopped letting their workers take time off to vote.”

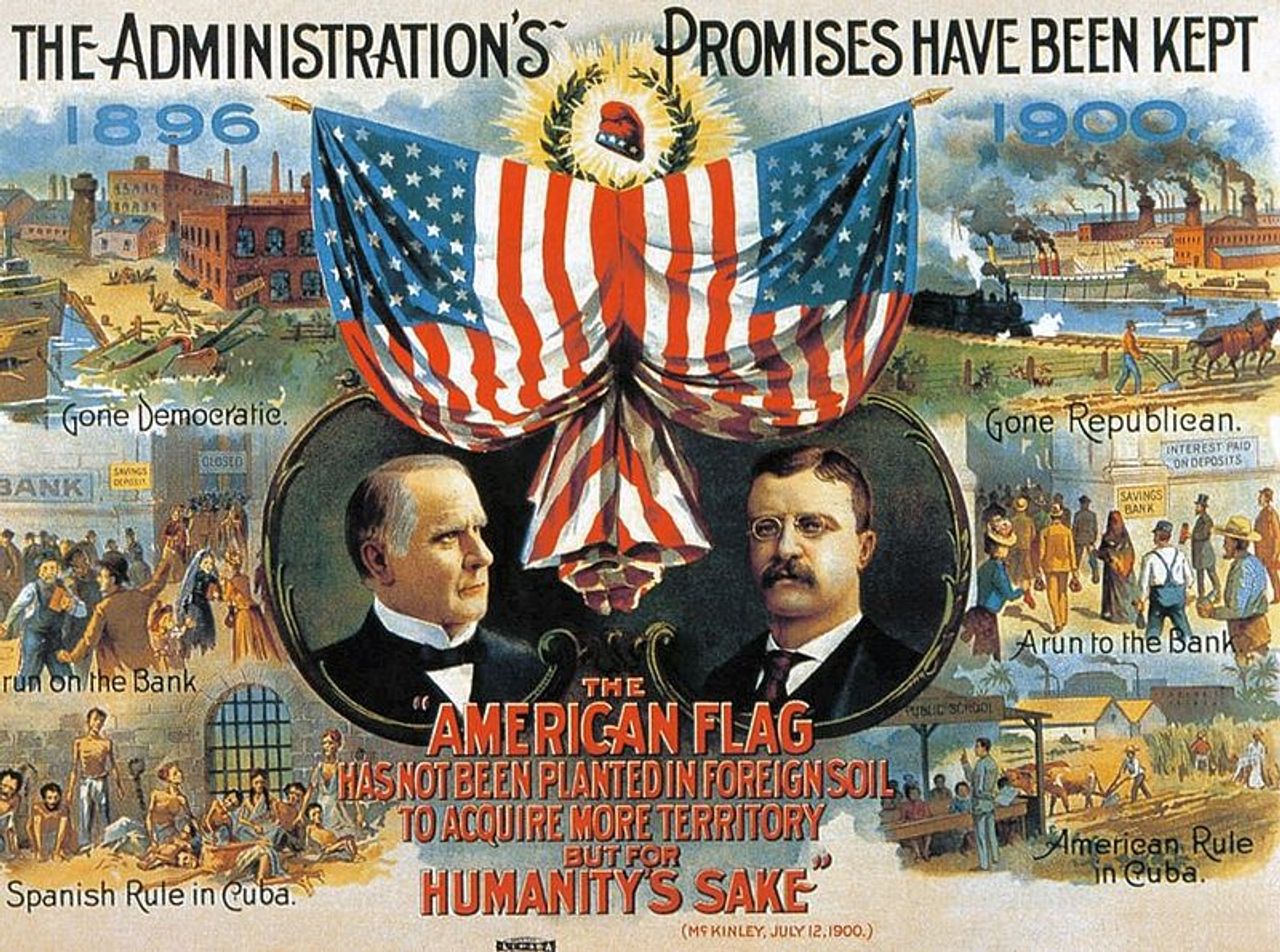

Republicans William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt won 1900 presidential election

This all accompanied—paradoxically it would seem—the Progressive Era of the first two decades of the 20th century. It was not, in fact, at all inconsistent. Many reformers found the infringement of voting rights perfectly acceptable, just as they supported the contemporaneous efforts to restrict immigration, efforts that led to the passage of the draconian Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which imposed quotas that reduced immigration from southern and eastern Europe to a small fraction of previous levels, while banning immigration from most of Asia.

The reformist wing of the ruling class saw measures such as antitrust laws, factory inspections, the end of child labor and similar legislation as necessary to forestall revolution. This became especially urgent after the 1905 Revolution in Russia, to which the author briefly alludes. The reforms that ascendant American capitalism could then afford were not the result of the sudden growth of charity among the employers. They came in response to the continuing development of the class struggle, including the founding and early growth of the Industrial Workers of the World. This period also corresponded to the emergence of the United States as an imperialist power, able to bribe a labor aristocracy—a thin layer of labor bureaucrats and privileged workers.

Not surprisingly, Grinspan discounts the growth of the socialist movement, barely mentioning Eugene Debs in an aside. He separates the relatively small socialist movement from the great stirrings of the working class, and accepts the falsehood that socialism was alien to the US. He neglects to mention the enormous impact in the US of the 1917 Russian Revolution, as well as internationally, and the leadership role of socialists and communists in the building of the industrial unions in the US in later decades.

This all accompanied—paradoxically it would seem—the Progressive Era of the first two decades of the 20th century. It was not, in fact, at all inconsistent. Many reformers found the infringement of voting rights perfectly acceptable, just as they supported the contemporaneous efforts to restrict immigration, efforts that led to the passage of the draconian Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which imposed quotas that reduced immigration from southern and eastern Europe to a small fraction of previous levels, while banning immigration from most of Asia.

The reformist wing of the ruling class saw measures such as antitrust laws, factory inspections, the end of child labor and similar legislation as necessary to forestall revolution. This became especially urgent after the 1905 Revolution in Russia, to which the author briefly alludes. The reforms that ascendant American capitalism could then afford were not the result of the sudden growth of charity among the employers. They came in response to the continuing development of the class struggle, including the founding and early growth of the Industrial Workers of the World. This period also corresponded to the emergence of the United States as an imperialist power, able to bribe a labor aristocracy—a thin layer of labor bureaucrats and privileged workers.

Not surprisingly, Grinspan discounts the growth of the socialist movement, barely mentioning Eugene Debs in an aside. He separates the relatively small socialist movement from the great stirrings of the working class, and accepts the falsehood that socialism was alien to the US. He neglects to mention the enormous impact in the US of the 1917 Russian Revolution, as well as internationally, and the leadership role of socialists and communists in the building of the industrial unions in the US in later decades.

The infringements on voting met with a good deal of success. Voter turnout fell from a high of 82.6 percent of eligible voters in 1876 to 48.9 percent in 1924. Grinspan writes: “From 1896 to 1900, turnout fell 6.1 percent. It crashed another 8 percent by 1904, plunged 6.6 percent in 1912, and crashed a full 12.4 percent by 1920.” By 1924, he continues, “for the first time in the history of American democracy, stay-at-homes made up the majority of eligible voters.”

The collapse of voting “was most extreme in the Deep South, where Jim Crow voting laws disenfranchised Black voters, discouraged poor Whites, and enthroned a small, White, wealthy, Democratic electorate. On average, half as many Southerners voted after 1900 as before.” This was not confined to the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. “In Florida, turnout dropped 52 percent; in South Carolina it fell 65.6 percent between 1880 and 1916. Just 17.5 percent of eligible South Carolinians voted in 1916…”

Grinspan is informative when demonstrating that race was not the only factor, and not even the biggest factor, in the hollowing out of American democracy over the last century. Voter turnout fell during this period, he writes, “especially among populations who were poorer, younger, immigrants or African-Americans. Election Day in the 19th century was a thrilling holiday. In the 20th century, it required literacy, identification papers, education, leave from work …”

He refers to Joe Biden’s hypocritical warning about new voting laws that risk “backsliding into the days of Jim Crow,” and adds, “… there is a stronger, subtler parallel: the deliberate discouragement of working class voters, around 1900, by wealthier Americans scared that ‘hordes of native and foreign barbarians, all armed with the ballot’ would replace them at the polls.”

The Jim Crow measures, accompanied by violence or the threat of violence, were the most blatant, but they were part of a broader pattern. As Grinspan notes, “while the Voting Rights Act of 1965 fought racial discrimination in voting, the discouragements preventing low-income participation have never been addressed.” He points out that the 66 percent turnout in the polarized election of 2020 was the highest percentage in 120 years and was far below the participation of eligible voters in the late 19th century. Thus, during a century when American imperialism regularly posed as the symbol of democracy, it was effectively disenfranchising many millions of its own citizens.

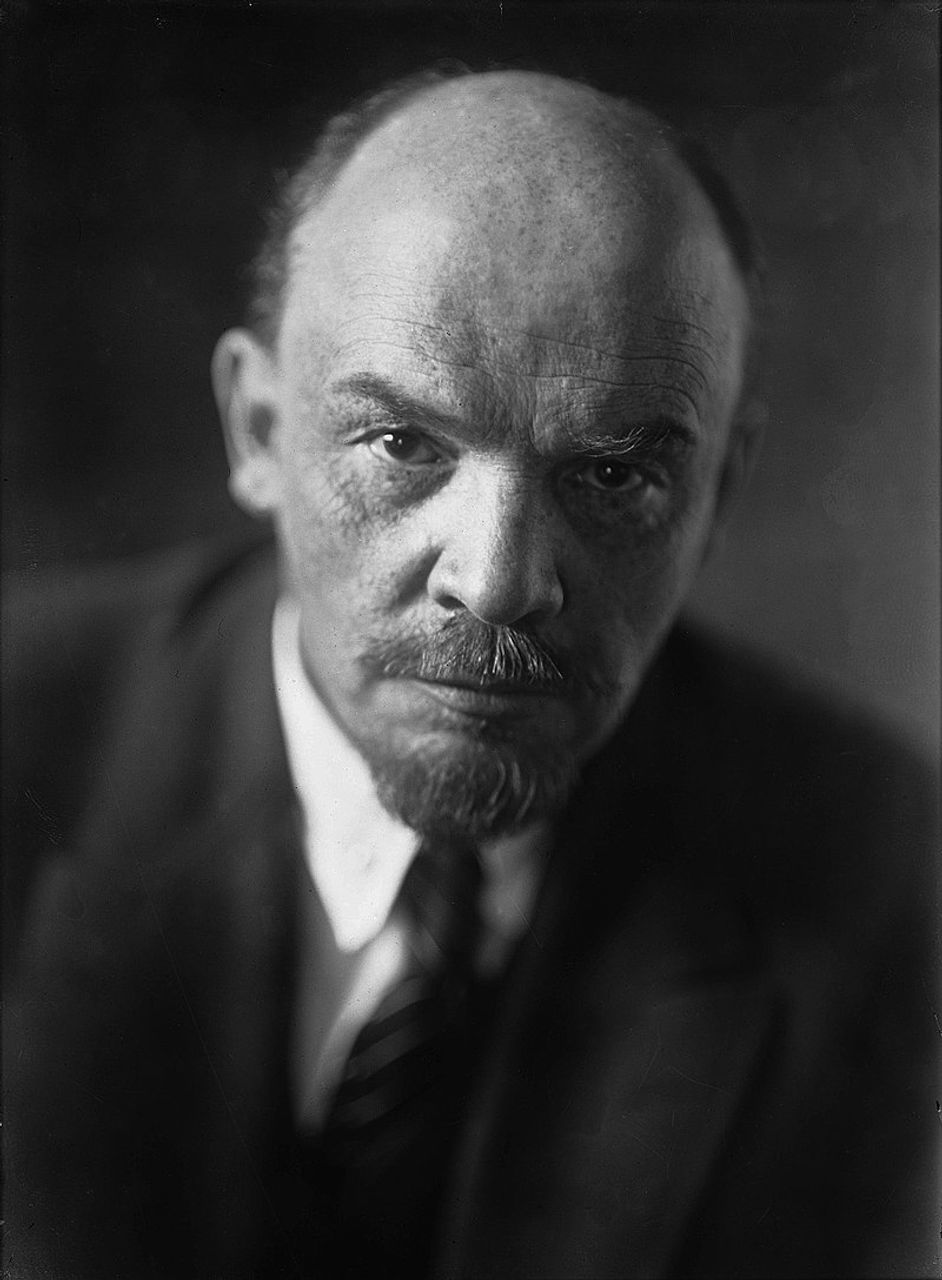

While Grinspan himself may shrink from this conclusion, his study and the statistics he compiles confirm the words of Lenin, the leader of the 1917 October Revolution, on the nature of democracy under capitalism:

Bourgeois democracy, although a great historical advance in comparison with medievalism, always remains, and under capitalism is bound to remain, restricted, truncated, false and hypocritical, a paradise for the rich and a snare and deception for the exploited, for the poor.

The collapse of voting “was most extreme in the Deep South, where Jim Crow voting laws disenfranchised Black voters, discouraged poor Whites, and enthroned a small, White, wealthy, Democratic electorate. On average, half as many Southerners voted after 1900 as before.” This was not confined to the disenfranchisement of African-Americans. “In Florida, turnout dropped 52 percent; in South Carolina it fell 65.6 percent between 1880 and 1916. Just 17.5 percent of eligible South Carolinians voted in 1916…”

Grinspan is informative when demonstrating that race was not the only factor, and not even the biggest factor, in the hollowing out of American democracy over the last century. Voter turnout fell during this period, he writes, “especially among populations who were poorer, younger, immigrants or African-Americans. Election Day in the 19th century was a thrilling holiday. In the 20th century, it required literacy, identification papers, education, leave from work …”

He refers to Joe Biden’s hypocritical warning about new voting laws that risk “backsliding into the days of Jim Crow,” and adds, “… there is a stronger, subtler parallel: the deliberate discouragement of working class voters, around 1900, by wealthier Americans scared that ‘hordes of native and foreign barbarians, all armed with the ballot’ would replace them at the polls.”

The Jim Crow measures, accompanied by violence or the threat of violence, were the most blatant, but they were part of a broader pattern. As Grinspan notes, “while the Voting Rights Act of 1965 fought racial discrimination in voting, the discouragements preventing low-income participation have never been addressed.” He points out that the 66 percent turnout in the polarized election of 2020 was the highest percentage in 120 years and was far below the participation of eligible voters in the late 19th century. Thus, during a century when American imperialism regularly posed as the symbol of democracy, it was effectively disenfranchising many millions of its own citizens.

While Grinspan himself may shrink from this conclusion, his study and the statistics he compiles confirm the words of Lenin, the leader of the 1917 October Revolution, on the nature of democracy under capitalism:

Bourgeois democracy, although a great historical advance in comparison with medievalism, always remains, and under capitalism is bound to remain, restricted, truncated, false and hypocritical, a paradise for the rich and a snare and deception for the exploited, for the poor.

Vladimir Lenin

This book brings its survey of US voting up only to the early 20th century, but it is necessary to consider at least briefly what has happened since 1915, and where American democracy stands today. The relatively stable two-party system inaugurated in the early 20th century has endured, with some minor challenges, until fairly recently. The American working class has remained politically disenfranchised, failing to build mass parties as happened in Europe and elsewhere.

This can be ascribed in part to the remaining resources of US imperialism, as the leading global capitalist power. In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was able to pose as the “friend of labor” and steal the political thunder of fascistic figures like Huey Long.

Even more decisive, however, was the crisis of working-class leadership, and above all the role of Stalinism, in systematically betraying the working class internationally. In the US, the Stalinists were crucial in helping to tie the insurgent labor movement to Roosevelt’s Democrats, and in the post-World War II period the anticommunist trade union bureaucracy, basing itself on the temporary postwar boom, took over the task of strangling the movement of the working class.

The last four decades, however, have witnessed a fundamental change. Everywhere the existing parties and trade unions—including the Stalinists—have been transformed and integrated into the capitalist state. Racial politics, in the form of the identity politics embraced by the Democrats, has supplemented racism and xenophobia as a means of dividing the working class. The accelerating crisis and decline of American capitalism has led, especially since the stolen election of 2000, to new and more extreme attacks on basic democratic rights.

This book brings its survey of US voting up only to the early 20th century, but it is necessary to consider at least briefly what has happened since 1915, and where American democracy stands today. The relatively stable two-party system inaugurated in the early 20th century has endured, with some minor challenges, until fairly recently. The American working class has remained politically disenfranchised, failing to build mass parties as happened in Europe and elsewhere.

This can be ascribed in part to the remaining resources of US imperialism, as the leading global capitalist power. In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was able to pose as the “friend of labor” and steal the political thunder of fascistic figures like Huey Long.

Even more decisive, however, was the crisis of working-class leadership, and above all the role of Stalinism, in systematically betraying the working class internationally. In the US, the Stalinists were crucial in helping to tie the insurgent labor movement to Roosevelt’s Democrats, and in the post-World War II period the anticommunist trade union bureaucracy, basing itself on the temporary postwar boom, took over the task of strangling the movement of the working class.

The last four decades, however, have witnessed a fundamental change. Everywhere the existing parties and trade unions—including the Stalinists—have been transformed and integrated into the capitalist state. Racial politics, in the form of the identity politics embraced by the Democrats, has supplemented racism and xenophobia as a means of dividing the working class. The accelerating crisis and decline of American capitalism has led, especially since the stolen election of 2000, to new and more extreme attacks on basic democratic rights.

This is part of the explosive growth of inequality, a Second Gilded Age even more extreme than the first. This level of inequality is not compatible with rights that have been won or tolerated in the past. This is the significance of the emergence of Trump, the ongoing transformation of the Republicans into a fascist party, and the complicity and bankruptcy of the Democrats in the face of the fascist danger.

This deepening onslaught on the working class is provoking a response, visible today in such developments as the growing strike wave as well as the mass protests against police killings. A period of revolutionary struggle has opened up, in the US and internationally.

The defense of the right to vote is bound up with the struggle for the political independence of the working class. It must answer the capitalist state’s suppression of democracy with genuine workers’ democracy and a workers’ state. The fight for socialism, smashing the capitalist class’s stranglehold on economic life, is the only answer to the COVID-19 pandemic and the threat of war and fascist dictatorship.

No comments:

Post a Comment