AFP•February 24, 2020

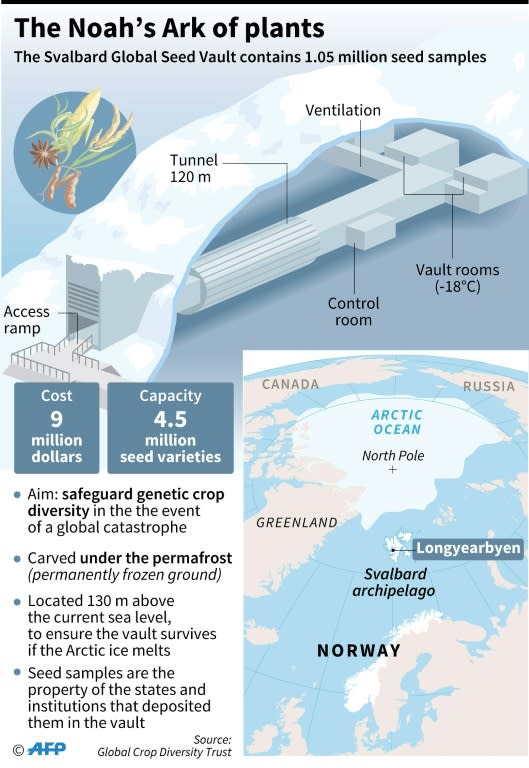

The latest shipment will bring to around 1.05 million the number of seed varieties placed in three underground alcoves which form the Arctic "doomsday vault", known also as Noah's Ark (AFP Photo/Helene DAUSCHY)

Oslo (AFP) - An Arctic "doomsday vault" is set Tuesday to receive 60,000 samples of seeds from around the world as the biggest global crop reserve stocks up for a global catastrophe.

The seeds are to be deposited in the vault inside a mountain near Longyearbyen on Spitsbergen Island in Norway's Svalbard archipelago, about 1,000 kilometres (600 miles) from the North Pole.

"As the pace of climate change and biodiversity loss increases, there is new urgency surrounding efforts to save food crops at risk of extinction," said Stefan Schmitz, who manages the reserve as head of the Crop Trust.

"The large scope of today’s seed deposit reflects worldwide concern about the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss on food production," Schmitz added.

"But more importantly it demonstrates a growing global commitment –- from the institutions and countries that have made deposits today and indeed the world –- to the conservation and use of the crop diversity that is crucial for farmers in their efforts to adapt to changing growing conditions," he said.

Common as well as wilder varieties of grains are being sent by institutions in countries as diverse as Brazil, the United States, Germany, Morocco, Mali, Israel and Mongolia.

The latest shipment will bring to around 1.05 million the number of seed varieties placed in three underground alcoves which form the vault, known also as Noah's Ark.

Aimed at safeguarding biodiversity in the face of climate change, wars and other natural and man-made disasters, the seed bank has the capacity to hold up to 4.5 million batches, or twice the number of crop varieties believed to exist in the world today.

It was launched in 2008 with financing from Norway.

Its usefulness was spotlighted during Syria's civil war when researchers were able in 2015 to retrieve from the vault duplicates of grains lost in the destruction of Aleppo.

The countries and institutions that deposit seeds in the vault retain ownership over them and can retrieve them when necessary.

Paradoxically, the vault was itself hit by climate change.

In 2016, water seeped into the vault's tunnel entrance due to permafrost melting as Arctic temperatures climbed unusually high.

Newly waterproofed Arctic seed vault hits 1m samples

Rapid climate change forced urgent upgrade of ‘failsafe’ doomsday storage facility

The Arctic global seed vault has reached the milestone of having 1m varieties stored in its deep freeze. The new deposits are being made after unexpected flooding of its entrance tunnel in 2017 prompted an upgrade.

Seeds from 60,000 crop varieties from across the world are being placed in the vault to back up those held in other seed banks.

The €9m (£7.5m) underground facility in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard opened in 2008 as a “failsafe” store. But the unexpectedly rapid pace of global heating led to melting of the permafrost that had encased it.

Now, a €20m refurbishment by the Norwegian government means the vault is secure for the future and “absolutely watertight”, according to officials.

The destruction of nature means vital diversity of crops and their wild relatives are being lost, at a time when the impact of the climate emergency means new varieties are needed to cope with changing weather and pests. Seed banks can also be destroyed by power loss and war, as happened in Aleppo, Syria, making the Svalbard vault crucial.

Tuesday’s deposits, from 36 institutions, are the most diverse and include seeds of 27 wild plants from Prince Charles’s Highgrove estateas well as seeds of the candy roaster squash, which are being deposited by the Cherokee Nation in the US.

Wild emmer wheat, known as the “mother of wheat” when it was discovered in 1906, is being deposited by Haifa University in Israel, alongside potato varieties from Peru and other crops from Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar and New Zealand. Each sample contains roughly 500 seeds.

The Svalbard vault, which is carved into solid rock, houses samples of about 1,050,000 crop varieties from 5,000 species. This represents two-fifths of the estimated 2.4m varieties in the world, and the vault has plenty of room to accommodate them.

“Crop diversity is an essential basis of food production,” said Hannes Dempewolf, a scientist at Crop Trust, which operates the vault alongside the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre. “And the Svalbard vault is the essential backup facility for seed banks around the world, safeguarding the biodiversity they hold.”

Many crop varieties have been lost, including 93% of fruit and vegetable varieties in the US.

“The issue of some water intrusion in the entrance tunnel was certainly not foreseen during construction,” Dempewolf said. “No one thought summers would be so warm.

Timeline

Half a century of dither and denial – a climate crisis timeline

“A major upgrade was the only right thing to do and the Norwegian government has certainly put the resources up to make sure that it is absolutely watertight now.”

Hege Njaa Aschim, a spokeswoman for the government, which owns the vault, said: “The entrance tunnel and the upgrade will secure the seed vault for the future.”

In 2017, she told the Guardian: “A lot of water went into the start of the tunnel … The vault was supposed to [operate] without the help of humans.” No water reached the seed vaults.

The 130-metre entrance tunnel has been fully waterproofed and the cooling equipment that keeps the vault at -18C moved to a new service building, so heat from the machinery can be released outside. The vault is 130 metres above sea level and designed for a “virtually infinite lifetime”.

“It is always dangerous to talk about something being completely failsafe and impregnable,” Dempewolf said. “In 20, 30, 40 years down the line, we will continue to monitor the situation to see whether any other upgrades are necessary.”

Norway has since financed work to insulate the vault from further effects of a warming and wetter climate, which scientists say is happening two times faster in the Arctic than elsewhere.