Abortion rights had a surprisingly hopeful day in the Supreme Court

Louisiana’s lawyer did such a bad job defending an anti-abortion law that she may have lost Chief Justice Roberts.

By Ian Millhiser Mar 4, 2020

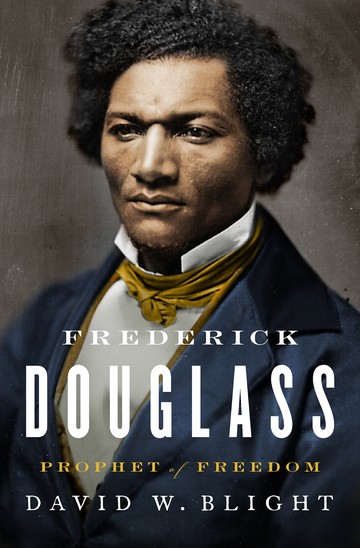

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66436610/20200304_Vox_SCOTUS240.7.jpg)

Thousands of protesters gathered outside the Supreme Court on Wednesday morning as oral arguments were underway over a restrictive Louisiana abortion law. Melissa Lyttle for Vox

Wednesday morning’s arguments in the biggest threat to abortion rights to reach the Supreme Court in nearly 30 years went so badly for Louisiana Solicitor General Elizabeth Murrill, who was defending Louisiana’s restrictive abortion law, that by the end even Chief Justice John Roberts appeared uncomfortable with her arguments.

Murrill spent 20 awkward minutes appearing to test whether it is possible to botch an argument badly enough to lose a case widely expected to go her way.

Given that conservatives hold the power on the Supreme Court, Louisiana still remains likely to prevail in June Medical Services LLC v. Russo. But Murrill’s performance was so weak, and the liberal justices successfully exposed so many flaws in her argument, that it raised questions about whether Roberts might join his liberal colleagues to strike down Louisiana’s law.

Wednesday morning’s arguments in the biggest threat to abortion rights to reach the Supreme Court in nearly 30 years went so badly for Louisiana Solicitor General Elizabeth Murrill, who was defending Louisiana’s restrictive abortion law, that by the end even Chief Justice John Roberts appeared uncomfortable with her arguments.

Murrill spent 20 awkward minutes appearing to test whether it is possible to botch an argument badly enough to lose a case widely expected to go her way.

Given that conservatives hold the power on the Supreme Court, Louisiana still remains likely to prevail in June Medical Services LLC v. Russo. But Murrill’s performance was so weak, and the liberal justices successfully exposed so many flaws in her argument, that it raised questions about whether Roberts might join his liberal colleagues to strike down Louisiana’s law.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19767322/GettyImages_1198751388.jpg)

Chief Justice Roberts could join his liberal colleagues after hearing arguments in Louisiana’s restrictive abortion law. Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call via Getty Images

June Medical involves a Louisiana law that requires abortion doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital that is within 30 miles of the clinic where the doctor provides abortion care. If that law sounds familiar, it should: Less than four years ago, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016), the Supreme Court struck down a Texas law that is virtually identical to the one at issue in June Medical.

Indeed, the only real distinction between Whole Woman’s Health and June Medical is the makeup of the Supreme Court. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who retired in 2018, was an uneasy defender of the right to an abortion. Though he typically voted to uphold abortion restrictions, he refused to overrule Roe v. Wade (1973) outright. And he joined his liberal colleagues in Whole Woman’s Health.

Kennedy’s replacement, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, has historically been much more skeptical of abortion rights. And his questions at Wednesday’s oral argument left few doubts that he will vote to uphold Louisiana’s law.

Yet the case appeared to turn on Roberts, who joined the dissent in Whole Woman’s Health and who almost always votes to uphold abortion restrictions. Roberts repeatedly asked whether there is any difference between the burden the Texas law struck down in Whole Woman’s Health imposes on people seeking abortions and the burden imposed by the nearly identical Louisiana law.

Neither Murrill nor US Principal Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, who defended the law on behalf of the Trump administration, was able to give Roberts a straight answer.

Louisiana tried to restrict abortion through a sham health law

Abortion rights advocates refer to laws like the one at in June Medical as “targeted restrictions on abortion providers,” or “TRAP” laws. TRAP laws superficially appear to make abortions safer, but they do very little to advance patient health — while simultaneously making it much harder to operate an abortion clinic.

Louisiana claims that its admitting privileges law serves two interlocking purposes. It is a credentialing requirement, which supposedly helps screen out incompetent doctors who shouldn’t perform abortions. And it is supposed to ensure that abortion patients who experience complications can be admitted to a nearby hospital by the doctor who performed the abortion.

RELATED

Getting an abortion in “the most pro-life state in America”

Yet, as the four liberal justices took turns pointing out, neither of these goals is meaningfully advanced by this particular law.

As Justice Elena Kagan noted, for example, hospitals often rely on criteria other than the quality of a physician when deciding whether to give a particular doctor admitting privileges. Many hospitals only give such privileges to doctors with a sufficient number of patients, who admit a certain number of patients every year to that hospital. Others outright refuse to give privileges to abortion providers.

Additionally, the law’s requirement that abortion providers have admitting privileges near their clinic undercuts the state’s argument that the law serves to screen out bad doctors. There’s no reason to believe that hospitals near clinics do a better job of screening doctors than hospitals far from clinics.

Similarly, the fact that so many hospitals require doctors to admit a certain number of patients if they want to receive privileges is a special barrier to abortion providers, because abortions are a very safe medical procedure. As Kagan explained, the clinic that brought this lawsuit has performed around 70,000 abortions. It’s transferred only four of those patients to a hospital. These doctors would struggle to meet their quotas because their patients are so unlikely to require medical care.

And there’s another reason an abortion doctor is unlikely to need to admit one of their patients to a nearby hospital. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg repeatedly pointed out, many abortion clinics perform medication abortions — meaning that the patient is given pills to take in the comfort of their own home. Even if a complication does arise, this patient is unlikely to seek care from a hospital near the clinic. They will seek care from a hospital close to their home, which is likely to be outside the 30-mile radius prescribed by the Louisiana law.

The Supreme Court held in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) that “unnecessary health regulations that have the purpose or effect of presenting a substantial obstacle to a woman seeking an abortion impose an undue burden on the right,” and both Murrill and Wall struggled to explain why this particular law isn’t an “unnecessary health regulation.”

These weaknesses in Louisiana’s arguments seemed to trouble Chief Justice Roberts: Twice, Roberts inquired what the “benefits” of such a law were, and he did so in a way that directly contradicted the state’s defense of its law.

The core of the state’s argument, after all, is that its admitting privileges law benefits abortion patients by making abortions safer — and that it does so even though the Supreme Court held in Whole Woman’s Health that a very similar Texas law does not benefit such patients. But Roberts appeared to reject this argument rather explicitly.

“I understand the idea that the impact might be different in different places,” the chief justice told Murrill at one point, “but as far as the benefits of the law, that’s going to be the same in each state, isn’t it?”

June Medical involves a Louisiana law that requires abortion doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital that is within 30 miles of the clinic where the doctor provides abortion care. If that law sounds familiar, it should: Less than four years ago, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016), the Supreme Court struck down a Texas law that is virtually identical to the one at issue in June Medical.

Indeed, the only real distinction between Whole Woman’s Health and June Medical is the makeup of the Supreme Court. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who retired in 2018, was an uneasy defender of the right to an abortion. Though he typically voted to uphold abortion restrictions, he refused to overrule Roe v. Wade (1973) outright. And he joined his liberal colleagues in Whole Woman’s Health.

Kennedy’s replacement, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, has historically been much more skeptical of abortion rights. And his questions at Wednesday’s oral argument left few doubts that he will vote to uphold Louisiana’s law.

Yet the case appeared to turn on Roberts, who joined the dissent in Whole Woman’s Health and who almost always votes to uphold abortion restrictions. Roberts repeatedly asked whether there is any difference between the burden the Texas law struck down in Whole Woman’s Health imposes on people seeking abortions and the burden imposed by the nearly identical Louisiana law.

Neither Murrill nor US Principal Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, who defended the law on behalf of the Trump administration, was able to give Roberts a straight answer.

Louisiana tried to restrict abortion through a sham health law

Abortion rights advocates refer to laws like the one at in June Medical as “targeted restrictions on abortion providers,” or “TRAP” laws. TRAP laws superficially appear to make abortions safer, but they do very little to advance patient health — while simultaneously making it much harder to operate an abortion clinic.

Louisiana claims that its admitting privileges law serves two interlocking purposes. It is a credentialing requirement, which supposedly helps screen out incompetent doctors who shouldn’t perform abortions. And it is supposed to ensure that abortion patients who experience complications can be admitted to a nearby hospital by the doctor who performed the abortion.

RELATED

Getting an abortion in “the most pro-life state in America”

Yet, as the four liberal justices took turns pointing out, neither of these goals is meaningfully advanced by this particular law.

As Justice Elena Kagan noted, for example, hospitals often rely on criteria other than the quality of a physician when deciding whether to give a particular doctor admitting privileges. Many hospitals only give such privileges to doctors with a sufficient number of patients, who admit a certain number of patients every year to that hospital. Others outright refuse to give privileges to abortion providers.

Additionally, the law’s requirement that abortion providers have admitting privileges near their clinic undercuts the state’s argument that the law serves to screen out bad doctors. There’s no reason to believe that hospitals near clinics do a better job of screening doctors than hospitals far from clinics.

Similarly, the fact that so many hospitals require doctors to admit a certain number of patients if they want to receive privileges is a special barrier to abortion providers, because abortions are a very safe medical procedure. As Kagan explained, the clinic that brought this lawsuit has performed around 70,000 abortions. It’s transferred only four of those patients to a hospital. These doctors would struggle to meet their quotas because their patients are so unlikely to require medical care.

And there’s another reason an abortion doctor is unlikely to need to admit one of their patients to a nearby hospital. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg repeatedly pointed out, many abortion clinics perform medication abortions — meaning that the patient is given pills to take in the comfort of their own home. Even if a complication does arise, this patient is unlikely to seek care from a hospital near the clinic. They will seek care from a hospital close to their home, which is likely to be outside the 30-mile radius prescribed by the Louisiana law.

The Supreme Court held in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) that “unnecessary health regulations that have the purpose or effect of presenting a substantial obstacle to a woman seeking an abortion impose an undue burden on the right,” and both Murrill and Wall struggled to explain why this particular law isn’t an “unnecessary health regulation.”

These weaknesses in Louisiana’s arguments seemed to trouble Chief Justice Roberts: Twice, Roberts inquired what the “benefits” of such a law were, and he did so in a way that directly contradicted the state’s defense of its law.

The core of the state’s argument, after all, is that its admitting privileges law benefits abortion patients by making abortions safer — and that it does so even though the Supreme Court held in Whole Woman’s Health that a very similar Texas law does not benefit such patients. But Roberts appeared to reject this argument rather explicitly.

“I understand the idea that the impact might be different in different places,” the chief justice told Murrill at one point, “but as far as the benefits of the law, that’s going to be the same in each state, isn’t it?”

Justices Alito and Kavanaugh offered competing arguments in defense of the anti-abortion law

Justice Samuel Alito, for his part, did his best to rescue Louisiana by arguing that the wrong party brought this particular lawsuit. In at least eight previous cases, the Supreme Court has allowed an abortion clinic or an abortion provider to bring a lawsuit challenging an abortion restriction. Alito argued that providers and clinics should be stripped of their ability to do so, meaning that future abortion suits would have to be brought by individual patients who are seeking an abortion.

But no other justice really picked up on this argument. Kavanaugh, meanwhile, suggested that maybe the Court’s decision in Whole Woman’s Health should be limited to just Texas. “What if all doctors in a state could easily get admitting privileges?” he asked at one point. Kavanaugh’s questions seemed to borrow from a federal appeals court opinion, which rather dubiously argued that Whole Woman’s Health should not apply in Louisiana because it is easier for Louisiana doctors to get admitting privileges than it is for Texas doctors to do so.

Roberts, for his part, initially seemed sympathetic to Kavanaugh’s argument. But his sympathy seemed to fade as the argument proceeded. Early in the argument, Roberts asked whether the question of whether a particular law violates Whole Woman’s Health is a “factual one that has to proceed state by state,” or whether all admitting privileges laws should be viewed with skepticism.

But the state was unable to demonstrate that Louisiana doctors will have an easy time getting admitting privileges. At one point, Justice Sonia Sotomayor rattled off individual doctors in Louisiana who struggled to get such privileges. At another point, Justice Stephen Breyer asked Murrill to identify which of the several doctors involved in this case presented the best case that Louisiana abortion providers can, indeed, get admitting privileges.

Murrill named a doctor who, according to the state’s own expert witness at trial, was unlikely to be able to obtain admitting privileges — an error that both Breyer and Sotomayor swiftly pounced on.

Indeed, by the end of the argument, Roberts appeared to explicitly reject Kavanaugh’s attempt to save the Louisiana law — wondering why it would make sense to treat every state differently when the (virtually nonexistent) benefits of an admitting privileges law are the same in every state.

The future of Roe v. Wade remains grim

Wednesday’s oral argument was not a high point for the anti-abortion movement. Murrill appeared unprepared for predictable questions, made tone-deaf arguments, and even argued with Ginsburg about the history of the Supreme Court’s feminist jurisprudence.

When Sotomayor asked Murrill whether a particular abortion provider performs surgical abortions, for example, Murrill did not appear to know the answer to the question — though she eventually replied that “to the best of my knowledge,” the doctor performs surgeries. Murrill contracted her state’s own expert witnesses and on many occasions seemed to contradict facts in the record.

At one point, Murrill got into an argument with Ginsburg, the most significant feminist lawyer in American history, about the facts of Craig v. Boren (1976), a seminal women’s rights decision that was heavily influenced by a brief filed by Ginsburg.

Murrill also came to Court to defend a law that is rooted in an outdated strategy.

TRAP laws made sense in a world where Kennedy, who was unwilling to overrule Roe but willing to uphold many abortion restrictions, held the crucial swing vote on abortion. They were a test of whether Kennedy would uphold severe restrictions on abortion, so long as those restrictions were written to look like a health regulation. That strategy failed in Whole Woman’s Health.

But TRAP laws were always rooted in deception. They depend on judges who are willing to pretend that an anti-abortion law that does nothing to protect patient health is, in fact, a health regulation.

On Wednesday, Roberts appeared uncomfortable with this deception. But even if he does vote to strike down this Louisiana law, there is a much more honest way for anti-abortion advocates to approach the Supreme Court in the future: They can simply ask Roberts to overrule Roe v. Wade. When that day comes, Roberts remains likely to give these advocates what they want.