Uma Ahmed

Late 2019, Jean Smale privately started to transition from male to female at the age of 73.

These days Jean Smale can look at herself in the mirror without discomfort at who stares back at her.

The name ‘Pamala’ had been picked out for Jean before her birth, as her mother was absolutely sure she was having a girl. However, on April 14, 1946, when Jean arrived in south Waikato, it was in the wrong body, she says.

In late 2019, Jean privately started to transition from male to female at the age of 73.

As she sits happily in her Southland home, all dressed up, her nails freshly painted pink, she tells the story of her life.

“I didn’t just get up one morning and decide I wanted to be a girl. It’s been... you carry it with you all your life. You have it in your heart and in your head, it’s right there all the time.”

Growing up in the 1940s and 1950s was tough, especially for those who were different.

“You just couldn’t go out and say ‘oh mum, look I feel like I should be a girl’ because mum probably would have picked up the kindling and given you a hiding to start with.

“And if the police had caught you, well you would have been put in jail... if you were caught wearing women’s clothes, well that would put you in an institution,” she explained.

KAVINDA HERATH/STUFF

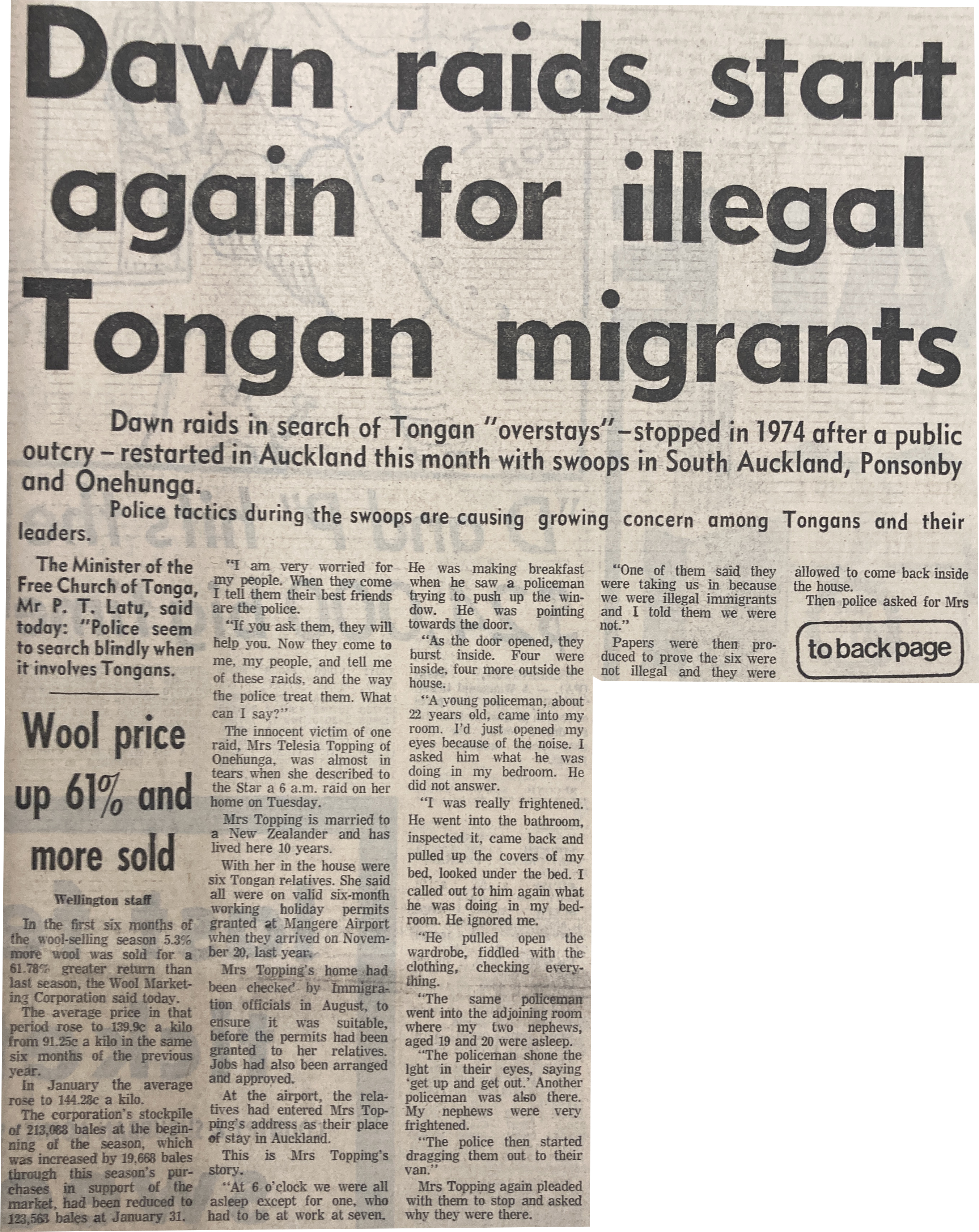

Jean Smale has been loving experimenting with different shades of pinks since she came out. Before, in fear of being found out, she stuck to greys. “I’m wearing colours, I’ve got jerseys and things like that, that are all bright colours and what have you ... which I would never have done before.”

It was because of these fears, Jean always stayed silent.

Jean’s parents have long passed away, and she does not think they ever had an inkling that she felt she was in the wrong body.

When asked what their reactions would be if they saw her today, Jean said: “I think they’d be horrified. Um yeah, I don’t think they’d understand at all.”

So, during the years she carried on with her life and tried to do “blokey things” because she looked like one and that was what was expected of her, she said.

“You didn’t talk about these things, they were all kept behind, you know, the closed doors.”

She never felt like she fitted in and there were a few things especially that made her feel uncomfortable, such as using the men’s urinals: “It just embarrassed me. I always did and for many years I’d just gone to the nearest cubicle I could find,” she recalls.

Jean always felt an affinity with females.

KAVINDA HERATH/STUFF

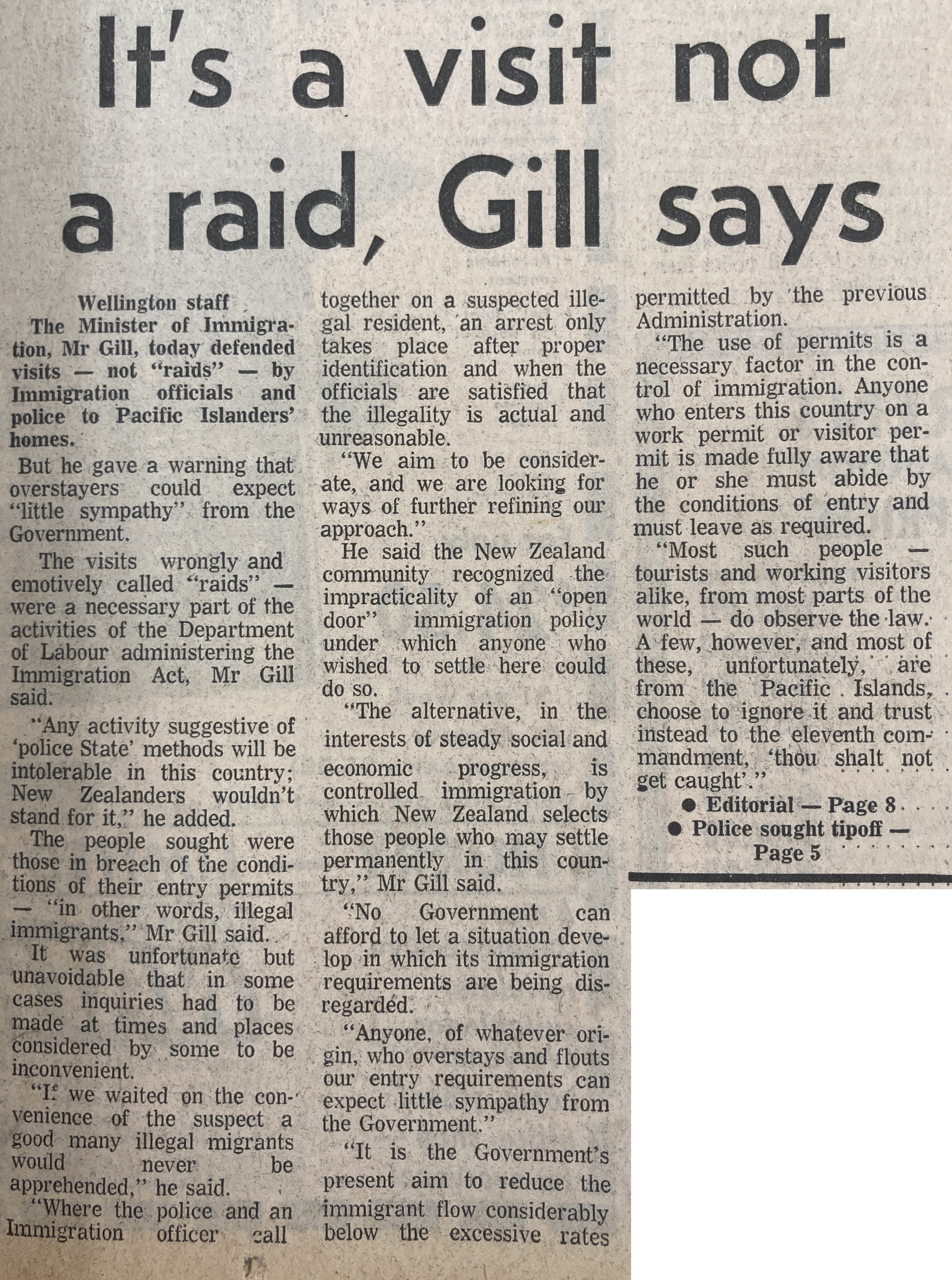

“I decided that for people to take me seriously, I should dress appropriately, so I probably over-dress a little bit maybe, but I like doing that.”

“People don’t realise what transgender actually is. We’re actually the people that are stuck in the middle. So, you have boys here, and you have girls there, and we’re stuck here in the middle. So, we’re a little bit of this, and a little bit of that. And it doesn’t matter which way you’re coming from, whether you’re a boy going to a girl or a girl going to a boy.”

She never felt comfortable in any of the clothes she wore and would simply resort to admiring from afar.

“It was just a longing, every time I saw adverts for women’s clothes and stuff like that, I would look at them and... you wouldn’t be able to say anything.

“In your mind you’d be saying ‘that’s a nice dress, I'd like to be able to wear that’. And you see girls getting their earrings or their ears pierced, their hair-dos and things like that, and you’d long for that sort of thing, but you just weren’t allowed to say anything.”

At age 17, Jean met 15-year-old Tina and fell in love. The couple married on November 23, 1968, and had a marriage of 50 years.

Jean and Tina went through many phases in their marriage. They moved various times, changed jobs, faced financial difficulties, and had problems with conceiving.

They went on to adopt two children in 1971 and 1973 before Tina gave birth to their youngest child in 1983.

Sometime in the 1980s, the family was living in the Bay of Plenty. Their two oldest children had left home and only the youngest was left in the coop. Tina had decided to become a nurse at that time and would be off for training sessions out of town. On occasion, she would be away for whole weeks at a time.

Jean would hold the fort while Tina was away. After the youngest would be off to school in the morning, Jean would have the house all to herself.

“And so I had these clothes and I just used to cross-dress... I’d come home from the cowshed and do the wee girl’s hair and... I would take her off to school, and I’d dress up and spend the day doing housework and spending my time dressed up,” Jean reveals.

Eventually, Jean confided in a good friend about what she had been up to while Tina was away, and she convinced Jean to tell Tina.

When Jean told Tina, her wife accepted her truth.

“She just knew that I had female feelings, and we just left it at that,” Jean said.

So, there was never really any discussions about Jean transitioning, probably because of the societal climate they were in.

“Because once you’ve got a family you don’t want to hurt them.”

Tina arranged an appointment with a hospital psychologist for Jean. The psychologist suggested Jean try and work at a female-oriented industry.

KAVINDA HERATH/STUFF

Jean Smale: “I have always hated mirrors. I would hate having to sit in front of a mirror while I had my hair cut. I didn’t like to look in the mirror because I couldn’t see the person I wanted to see in there.”

Tina was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Jean stayed with her until her death in 2019.

“We were co-dependent right from the very beginning,” she explains.

Jean felt lost afterward and decided to “run away” soon after Tina’s death.

She stocked up with extra fuel and headed north.

“As I was going along, I had this picture of Cape Reinga in my head and I didn’t know why.”

On her way, a stranger saw she was in distress, and they prayed together.

That night she realised why Cape Reinga had got stuck in her head: “My wife’s spirit. Because Māori legend has it that when a person dies, their spirit leaves from Cape Reinga, and so I thought right, that’s what I’m supposed to do.”

She held a ceremony with a kaumātua to farewell Tina’s spirit, and had a long cry afterwards. She stayed away for two months and when she returned to Southland, she was ready to transition.

Jean met up with a psychologist who told her there was nothing

KAVINDA HERATH/STUFF

Jean’s reasons for hiding her secret: “Because once you’ve got a family you don’t want to hurt them.”

“They’ve kind of become my family a bit. Because they’re all lovely caring people,” she says.

After that, she started to wear whatever caught her fancy, but in private. In September last year, after visiting a doctor regarding the future of her transition, she was ready to present herself to everyone.

“I just decided if I was going to do this, I had to go the whole hog, and so I’ve just put myself out in the community.

“I made it my job that I should go and train the village,” she says.

Jean has been pleasantly surprised with people's reactions, especially the women in her life who have taken her in, she says.

“People have got used to me, so I’m quite happy to go to town now.”

If there is one gripe Jean has with people’s reactions, it is that some people seem to think she decided to become a woman overnight because it is 2021, and she is trying to be “in” with the times.

“They think that I’m just dressing up to have an exciting feeling from wearing women’s clothes, but that’s not the case. I feel really comfortable; I feel like I belong in them,” she says.

Meeting the rainbow community, she has realised she was not the only one who tried to hurt herself during the years because she was ashamed of her own body.

Her psychiatrist informed her it was not unusual for transgender people to try and hurt themselves.

Things such as this are why Jean believes it is important to educate those around her and “train the village” as she likes to call it, to make it easier for others like her.

Jean is grateful that times have changed due to the younger generation being more accepting and open-minded.

She admits it has been hard for her children to accept her transition, but says they are starting to understand she did not make her decision on a whim.

“I was a good person before, and I’m still a good person," she says. “I’m just in a different package.”