ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

Today, federal officials are taking steps to close one of the most dangerous prison units in the country. The Special Management Unit of the Thomson Penitentiary in northwestern Illinois will shut down, and hundreds of inmates will move somewhere else within the federal prison system. This change came about because of murders and suicides among inmates at Thomson, violence that was exposed by the reporting of NPR and its partner, The Marshall Project. We'll warn you that this report includes some descriptions of that violence. NPR investigative correspondent Joseph Shapiro is here to talk with us about this development. Hi, Joe.

JOSEPH SHAPIRO, BYLINE: Hi, Ari.

A SHAPIRO: The federal officials who are shutting down this prison unit say they are doing so largely because of violent conditions which you documented in your reporting. Tell us what you found.

J SHAPIRO: That's right. This is reporting I did with Christie Thompson of The Marshall Project. And first, we found a string of violent deaths in just two years - five homicides - prisoners killing other prisoners - and two suicides. And there was another violent death - we're not sure what happened - just two weeks ago.

A SHAPIRO: The question is, why? What set this prison apart? Why was it so much more violent? What did your reporting show?

J SHAPIRO: Right. Well, it started with a little-known practice, something called double celling, which is the practice of putting two men into one tiny solitary confinement cell. It's about the size of a parking space. And they're locked down for 23, 24 hours a day. And we reported on men also placed in restraints, often painful, four-point restraints, for hours or days, often in violation of federal prison policies. This happened in a room that the prisoners told us they called the torture chamber. And these tight restraints would leave scars that the men told us they called their Thomson tattoos.

A SHAPIRO: A lot of your reporting relied on prisoners or their family members who courageously spoke up about these conditions, sometimes even though they feared that the prison system might retaliate against them. Can you introduce us to someone?

J SHAPIRO: Yes, one prisoner, Demetrius Hill. He was an eyewitness to a killing. And he got a message to us the day after it happened. A family told their stories of how corrections officers would often put men together as cellmates or in recreation yards, men who they knew were going to fight. Sue Phillips says guards put her son Matthew alone in a recreation cage with two members of a white supremacist gang, who then killed him. Matthew was Jewish. He had a large star of David tattooed on his chest. And the indictment of these men who were charged with killing him says they have their own tattoos for a prison gang called the Valhalla Bound Skinheads. Here's Sue Phillips. She's talking about what the indictment says was found in their cells.

SUE PHILLIPS: They had white supremacy markings on their shoes. They also had cells that contained Nazi memorabilia, mugs with swastikas on them, articles of literature promoting white supremacy, drawings of Hitler.

J SHAPIRO: These men brutally kicked and stomped her son. And Sue Phillips says corrections officers should have known what would happen when they put her son alone in that recreation cage with them.

A SHAPIRO: I understand the Bureau of Prisons won't say where these 500 or so inmates from Thomson will go, but based on your reporting, it does not seem safe to assume that this is necessarily going to solve the problem.

J SHAPIRO: Right. Christie Thompson and I have been writing for seven years now about problems at these special management units. They're supposed to be places that take the most violent, dangerous federal prisoners, gang leaders, ones who commit prison violence - although, by the way, we talked to men who didn't seem to fit any of those descriptions. Our first reporting found similar violence at the previous version of the special management unit at the federal prison at Lewisburg, Pa. And shortly after our reporting, that unit was moved to Thomson. And Thomson became another violence factory, which is why the Federal Bureau of Prisons now is shutting it down after its own investigation, which found the problems at Thomson are so deep and persistent that they figured the place can't be fixed. It's not clear, though, what will replace it. Or, as you said, where these men are going. But we're going to keep watching.

A SHAPIRO: That's NPR investigative correspondent Joseph Shapiro. Thank you.

J SHAPIRO: Thank you, Ari. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

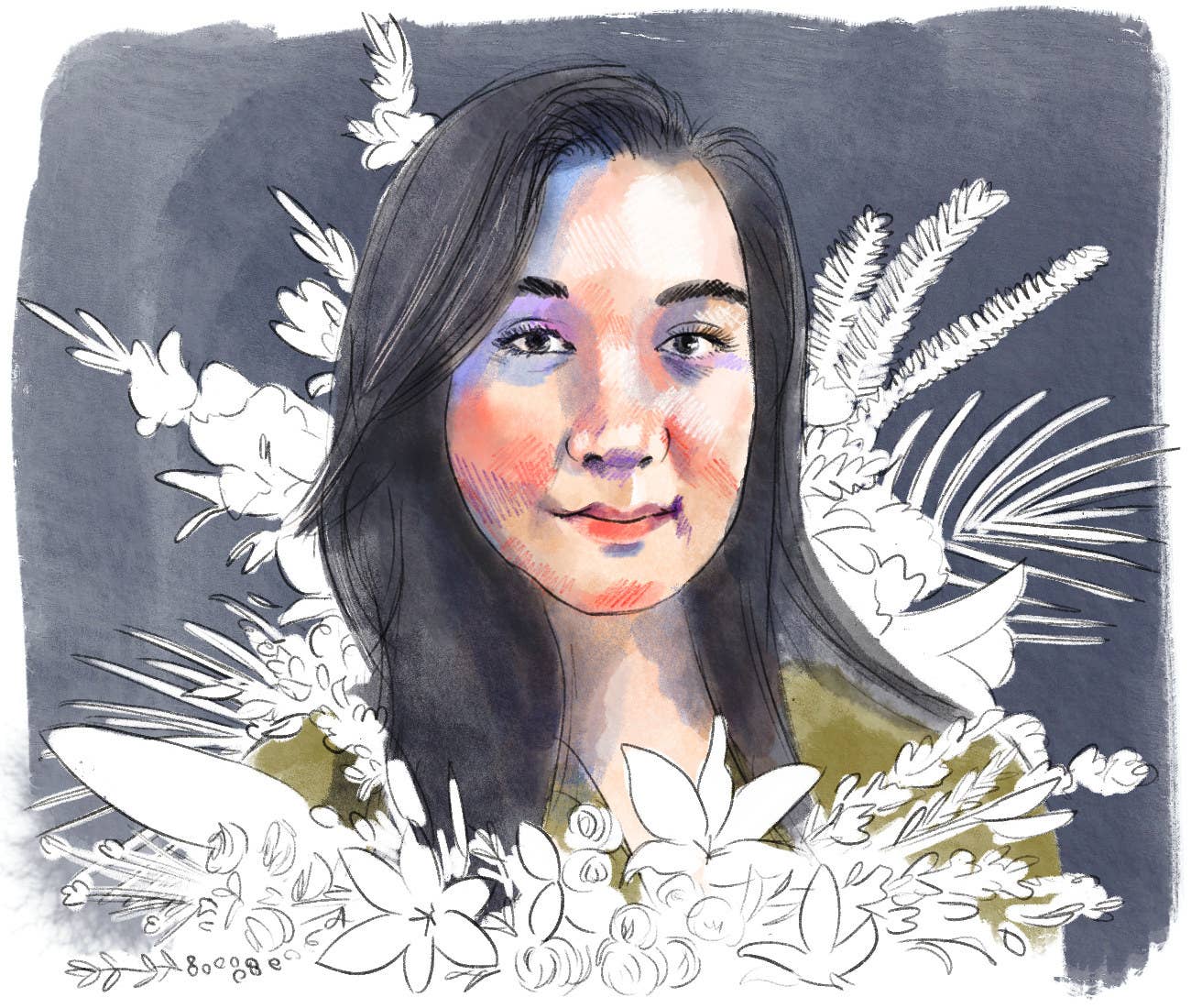

Brianna Ghey is shown in this undated photo released by the Cheshire Police

Brianna Ghey is shown in this undated photo released by the Cheshire Police

Published February 15, 2023

Published February 15, 2023