The NTSB has released its investigative report on the sinking of the towboat Jacqueline A, which sank while under tow in the Atlantic off the coast of South Carolina. The vessel went down because of corrosion holes in small void spaces above the lazarette, leading to water ingress and progressive flooding through unsealed wire runs between compartments.

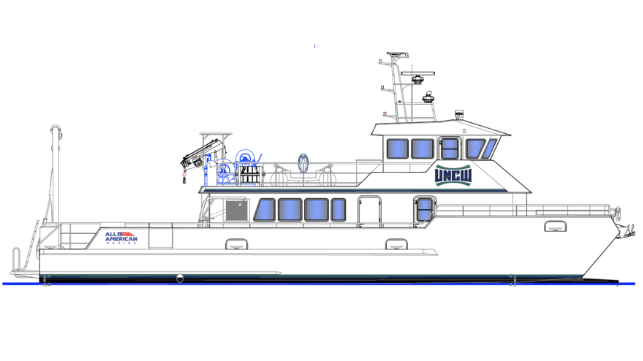

Jacqueline A was a 60-foot towboat built in 1981 as the Eric Paul. Since 2012, she had been in service with a small towing company in Weems, Virginia, and was used for barge tows on the Chesapeake Bay. She was taken out of service in 2019 because she was not compliant with the newly-crafted Subchapter M regulations for towing vessels, and was laid up for several years.

In mid-2023, the vessel's owner decided to return Jacqueline A to service and contracted with a yard in Louisiana to make upgrades and repairs. The owner hired a captain, mate and deckhand for a transit voyage to deliver the vessel to the yard. The captain said that the vessel's mechanical spaces looked to be in great shape, but the lazarette was not visually inspected immediately prior to the voyage (it had been checked three months earlier during a yard period).

The master got under way on August 6, 2023, and headed for the Intracoastal Waterway. As the weather improved, the master decided to take an open-ocean route from the Cape Fear River inlet in North Carolina to Port St. Lucie, Florida, saving time.

At about 1350 hours on August 8, the Jacqueline A left the Cape Fear River channel and headed southwest along the coastline. The seas were on the port beam at four feet, and the vessel was "rolling pretty good," according to the mate. The aft deck was taking water over the bulwarks, not unusual for a towing vessel in rough weather. Conditions subsided over the next few hours, but sea spray continued to wash over the vessel periodically.

Between 1830-1850, the captain - who was on watch - noticed that the towboat had taken on a port list. He went out of the wheelhouse on the port side to look aft, and he saw that the main deck was underwater up to the edge of the deckhouse.

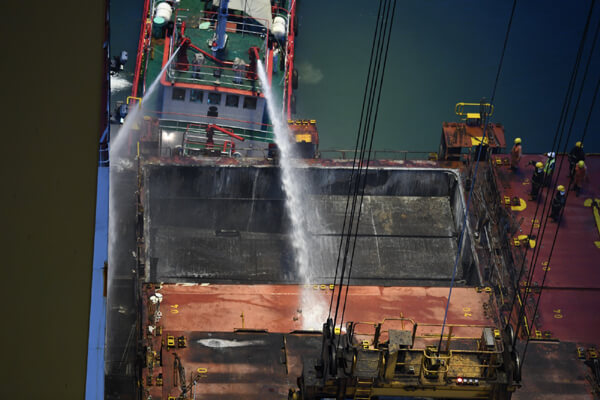

The master checked the engine room and found that water was spilling in from the two wire runs that connected the engine room to the lazarette. (Jacqueline A had two four-inch pipes running from the aft engine room to the lazarette, through the potable-water tanks. They were unsealed and open-ended.) There was water in the bilge up to the bottom of the engine on the port side. The crew attempted to start bilge pumps, but the situation rapidly deteriorated, and the Jacqueline A quickly took on a severe port list and aft trim.

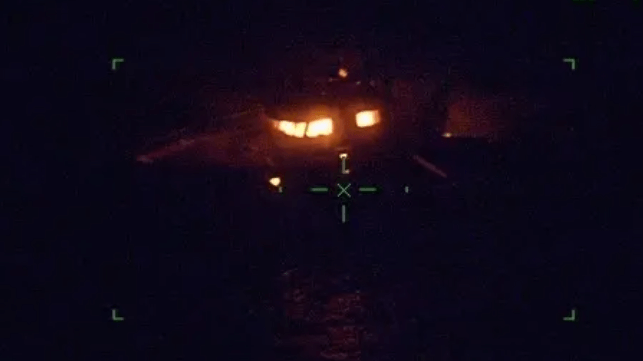

At 1856, the master made a mayday call and gave the Coast Guard the vessel's position - just in time, as the generator shut down and took out the radio shortly after.

The Jacqueline A began to go down quickly by the stern, but as she was only in 31 feet of water, her downward progress was arrested when her hull struck the bottom. The bow remained above the surface, and the crew moved forward of the wheelhouse, where they stayed to wait for a rescue.

Three near-shore response boats from local agencies arrived at about 1940 hours, and they took the crew aboard for safe delivery ashore. No injuries were reported; the Jacqueline A fully sank shortly after.

The vessel was raised by a salvage crew on August 21. The Jacqueline A's systems had sustained extensive damage throughout, and the cost of repairs was more than the value of the towboat, so she was declared a total loss.

During a post-casualty inspection, the inboard plating of the bulwarks was cut away, and revealed wastage with holes of 2-8 inches in diameter on the deck plating of the small void spaces inside. The exterior of the bulwarks also showed substantial wastage, some of which had been covered with fiberglass patches. The port engineer had identified the enclosed bulwarks as a hazard earlier, and they were due for removal during the Louisiana yard repair period.

There was also a previously-undetected hole on the stern hull plating - the aft bulkhead of the lazarette - that was less than one inch in diameter. Gaskets were also missing from weathertight doors on the deckhouse.

The Coast Guard's Marine Safety Center concluded that the Jacqueline A's lazarette began to flood through the small hole. As the stern sank lower, the holes in the deck would have accelerated the rate of flooding. Once the lazarette filled, it would have begun flooding the engine room via the unsealed wire runs at up to 1,100 gallons a minute. From start to finish, once the aft deck was submerged, the towboat would have gone down in 9-16 minutes.

"The lazarette was a relatively small space compared to the engine room. If the wire runs had been sealed, flooding would have been contained to the lazarette, and the vessel likely would have remained afloat," concluded NTSB.

The agency cautioned operators, yards and designers to avoid creating small void spaces, where moisture can accumulate undetected and lead to severe, undetectable corrosion. It also reminded owners of the need for proper sealing of wire runs and other penetrations through bulkheads, since holes enable progressive flooding.

Informally, NTSB noted that the crew could have observed the vessel's "poor material condition" when they arrived at the pier and should have conducted a more thorough inspection - including opening up the lazarette for a visual examination - before getting under way.