Law professor Charles Reich, author of ‘Greening of America,’ dies at 91

Steve Rubenstein

of the 1960s and became a million-selling manifesto for a new and

euphoric way of life.

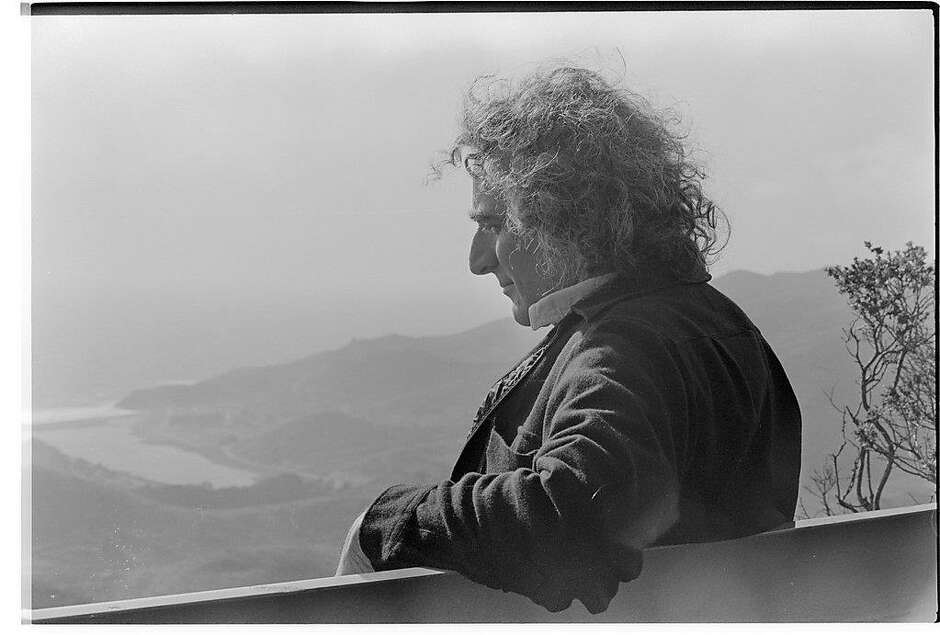

Photo: Roger Ressmeyer / Getty Images

Half a century ago, Yale law school professor Charles Reich wrote a million-seller book that had the country talking.

It was called “The Greening of America” and it was full of history and philosophy and predictions about America’s future, all wrapped up with something that Reich called Consciousness I, II and III.

The book was a sensation. In December 1970, it was the best-selling book in the country. A long excerpt ran in the New Yorker magazine. The engaging, brilliant and popular law school professor who loved nothing so much as a quiet walk in the woods suddenly found himself a national phenomenon.

That the work is little known or remembered today puzzled the author’s many friends and left Reich, who moved to San Francisco four decades ago, bemused and at least as philosophical as anything in his book.

Reich died June 15 in San Francisco of natural causes following a period of declining health. He was 91.

“He was brilliant, and he was respectful and warm, in a positive way,” recalled retired Stanford Law School professor Michael Wald, his longtime friend and former student. “It was a real treat to be in his class. Almost every day, at the end of class, his students stood and applauded.”

Another friend and former student, California Court of Appeal presiding Justice J. Anthony Kline, said Reich had an “inquiring mind and was a bit of a skeptic.”

He devoured books on any subject, from the history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to rock music.

“The key to his creativity,” said Kline, after thinking the matter over, “is that he was not vested in conventional verities.”

In “The Greening of America,” Reich declared that Consciousness III was represented by the counterculture of the 1960s, its free lifestyle and its use of recreational drugs. It replaced the earlier two “consciousnesses” represented by 19th century America and by the New Deal.

The cover of his book carried a five-sentence summary in large type — unusual for any book before or since — that proclaimed a coming revolution “will originate with the individual and with culture ... and will not require violence to succeed.”

Another friend, San Francisco environmental lawyer Trent Orr, called Reich “really smart and really fun, with some fairly out-there ideas that he wasn’t afraid to put out there.”

A native of New York City and a graduate of Oberlin College and Yale law school, Reich served as a clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black and became a close friend of Justice William O. Douglas. He taught at Yale from 1960 to 1974.

At Yale, Kline recalled, the young Reich was assigned to teach a course in property law, about which he complained he knew little. He threw himself into the subject and became an internationally known authority, writing a highly cited law review article on the changing notion of property rights and maintaining that property included not only real estate but such institutions as welfare benefits and professional licenses.

Among his other Yale students were a pair of ambitious idealists named Bill and Hillary Clinton.

In 1974, he moved to San Francisco and taught at University of San Francisco law school. He enjoyed the outdoors, books and long talks with friends.

“He was a complicated guy,” Kline said. “He became a celebrity, but becoming a celebrity was never something he aspired to.”

Of his book’s fall from popularity, Wald said, Reich had little time or inclination to be sad.

“The book had a big impact, and then the world changed,” Wald said. “It moved in a different direction.”

In a 2010 interview with CBS News, Reich mused on how the changes he foretold didn’t play out as he predicted.

“The things that troubled young people in the ’60s and the things that trouble young people today seem quite different, in the sense that the troubles today are mostly material trouble — I can’t get a job; I can’t support a family. Whereas the complaints in the 1960s were more spiritual — I don’t feel like a real person, or something like that,” he said.

“However,” he added, “whether you’re complaining about spiritual emptiness or material emptiness, you’re ultimately complaining about the same system that’s creating both kinds of emptiness. That’s the link between ‘The Greening of America’ and the way young people are feeling today.”Reich is survived by his nephew, Dan Reich, of Baltimore and by his niece, Alice Reich, of Philadelphia. A private memorial gathering was held in San Francisco.

Steve Rubenstein is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: srubenstein@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @SteveRubeSF

ERIC ED110384: The Future of Work and Leisure. ERIC Publication date 1975

Photo: Roger Ressmeyer / Getty Images

Half a century ago, Yale law school professor Charles Reich wrote a million-seller book that had the country talking.

It was called “The Greening of America” and it was full of history and philosophy and predictions about America’s future, all wrapped up with something that Reich called Consciousness I, II and III.

The book was a sensation. In December 1970, it was the best-selling book in the country. A long excerpt ran in the New Yorker magazine. The engaging, brilliant and popular law school professor who loved nothing so much as a quiet walk in the woods suddenly found himself a national phenomenon.

That the work is little known or remembered today puzzled the author’s many friends and left Reich, who moved to San Francisco four decades ago, bemused and at least as philosophical as anything in his book.

Reich died June 15 in San Francisco of natural causes following a period of declining health. He was 91.

“He was brilliant, and he was respectful and warm, in a positive way,” recalled retired Stanford Law School professor Michael Wald, his longtime friend and former student. “It was a real treat to be in his class. Almost every day, at the end of class, his students stood and applauded.”

Another friend and former student, California Court of Appeal presiding Justice J. Anthony Kline, said Reich had an “inquiring mind and was a bit of a skeptic.”

He devoured books on any subject, from the history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to rock music.

“The key to his creativity,” said Kline, after thinking the matter over, “is that he was not vested in conventional verities.”

In “The Greening of America,” Reich declared that Consciousness III was represented by the counterculture of the 1960s, its free lifestyle and its use of recreational drugs. It replaced the earlier two “consciousnesses” represented by 19th century America and by the New Deal.

The cover of his book carried a five-sentence summary in large type — unusual for any book before or since — that proclaimed a coming revolution “will originate with the individual and with culture ... and will not require violence to succeed.”

Another friend, San Francisco environmental lawyer Trent Orr, called Reich “really smart and really fun, with some fairly out-there ideas that he wasn’t afraid to put out there.”

A native of New York City and a graduate of Oberlin College and Yale law school, Reich served as a clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black and became a close friend of Justice William O. Douglas. He taught at Yale from 1960 to 1974.

At Yale, Kline recalled, the young Reich was assigned to teach a course in property law, about which he complained he knew little. He threw himself into the subject and became an internationally known authority, writing a highly cited law review article on the changing notion of property rights and maintaining that property included not only real estate but such institutions as welfare benefits and professional licenses.

Among his other Yale students were a pair of ambitious idealists named Bill and Hillary Clinton.

In 1974, he moved to San Francisco and taught at University of San Francisco law school. He enjoyed the outdoors, books and long talks with friends.

“He was a complicated guy,” Kline said. “He became a celebrity, but becoming a celebrity was never something he aspired to.”

Of his book’s fall from popularity, Wald said, Reich had little time or inclination to be sad.

“The book had a big impact, and then the world changed,” Wald said. “It moved in a different direction.”

In a 2010 interview with CBS News, Reich mused on how the changes he foretold didn’t play out as he predicted.

“The things that troubled young people in the ’60s and the things that trouble young people today seem quite different, in the sense that the troubles today are mostly material trouble — I can’t get a job; I can’t support a family. Whereas the complaints in the 1960s were more spiritual — I don’t feel like a real person, or something like that,” he said.

“However,” he added, “whether you’re complaining about spiritual emptiness or material emptiness, you’re ultimately complaining about the same system that’s creating both kinds of emptiness. That’s the link between ‘The Greening of America’ and the way young people are feeling today.”Reich is survived by his nephew, Dan Reich, of Baltimore and by his niece, Alice Reich, of Philadelphia. A private memorial gathering was held in San Francisco.

Steve Rubenstein is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: srubenstein@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @SteveRubeSF

ERIC ED110384: The Future of Work and Leisure. ERIC Publication date 1975

Topics ERIC Archive, Economic Climate, Employed Women, Futures (of Society), Labor Market, Leisure Time, Life Style, Population Trends, Prediction, Social Change, Sociocultural Patterns, Values, Work Attitudes

Collection ericarchive; additional_collections

Language English

Earlier projections of labor supply and speculations about the impact on values and lifestyles on work, leisure, and work-leisure relationships are reassessed in light of current events. Previous projections were the basis for three alternative scenarios of possible work-leisure relationships. The first examined some of the implications of arguments developed by Charles Reich in "The Greening of America." The second was developed as an antithesis to the first and traced the implications of a renewed commitment to full employment and the preservation of the traditional meaning of work. The third depicted a blending of the values and life styles of the first two. Upon examination after four years time, the elements which induced a preference for the third alternative require modification based on the increasing economic activities of women, the aging of the baby-boom, and the potential resource scarcities and recession. The emerging trends appear to suggest a shift from the third scenario to the second. Projections over the next quarter century and their implications are discussed. Footnotes and tables are included. (Author/KSM)

Book REVIEW / NONFICTION :

Collection ericarchive; additional_collections

Language English

Earlier projections of labor supply and speculations about the impact on values and lifestyles on work, leisure, and work-leisure relationships are reassessed in light of current events. Previous projections were the basis for three alternative scenarios of possible work-leisure relationships. The first examined some of the implications of arguments developed by Charles Reich in "The Greening of America." The second was developed as an antithesis to the first and traced the implications of a renewed commitment to full employment and the preservation of the traditional meaning of work. The third depicted a blending of the values and life styles of the first two. Upon examination after four years time, the elements which induced a preference for the third alternative require modification based on the increasing economic activities of women, the aging of the baby-boom, and the potential resource scarcities and recession. The emerging trends appear to suggest a shift from the third scenario to the second. Projections over the next quarter century and their implications are discussed. Footnotes and tables are included. (Author/KSM)

No, Higher Consciousness Won’t Save Us

Charles Reich (William K. Sacco/Yale University)

Autumn 2010 is a time of disillusionment for many who deplore the USA’s current political trajectory. Some who’ve been active for progressive causes are now gravitating toward hope that individual actions — in tandem with higher consciousness, more down-to-earth lifestyles and healthy cultural alternatives — can succeed where social activism has failed. It’s an old story that is also new.

From economic inequities to global warming to war, the nation’s power centers have repulsed those who recognize the urgency of confronting such crises head-on. High unemployment has become the new normal. Top officials in Washington have taken a dive on climate change. The warfare state is going great guns.

When social movements seem to be no match for a destructive status quo, people are apt to look around for alternative strategies. One of the big ones involves pursuing individual transformations as keys to social change. Forty years ago, such an approach became all the rage — boosted by a long essay that made a huge splash in The New Yorker magazine just before a longer version became a smash bestseller.

The book was The Greening of America, by a Yale University Law School teacher named Charles Reich. In the early fall of 1970, it created a sensation. Today, let’s consider it as a distant mirror that reflects some similar present-day illusions.

On the front cover of “The Greening of America,” big type proclaimed: “There is a revolution coming. It will not be like revolutions of the past. It will originate with the individual and with culture, and it will change the political structure only as its final act.”

That autumn, I was upbeat about Reich’s new book — including its great enthusiasm for “the revolution of the new generation.” (Hey, that was me and my friends!) The book condemned the war, denounced the overcapitalized Corporate State, panned the rigidity of schools, lauded the sensuality that marijuana was aiding, and dismissed as pathetically venal the liberalism that had driven the country to war in Vietnam.

At the time, I scarcely picked up on the fact that “The Greening of America” was purposely nonpolitical. Its crux was personal and cultural liberation — in a word, “consciousness,” which “plays the key role in the shaping of society.” And so, “The revolution must be cultural. For culture controls the economic and political machine, not vice versa.” In effect, the author maintained, culture would be a silver bullet, able to bring down the otherwise intractable death machine.

Let’s freeze frame those two dreamy claims and mull them over. Consciousness “plays the key role in the shaping of society.” And culture “controls the economic and political machine, not vice versa.”

Reich combined those outsize tributes to “consciousness” and “culture” with disdain for some plodding struggles. “The political activists have had their day and have been given their chance,” he wrote. “They ask for still more activism, still more dedication, still more self-sacrifice, believing more of the same bad medicine is needed, saying their cure has not yet been tested. It is time to realize that this form of activism merely affirms the State. Must we wait for fascism before we realize that political activism has failed?”

In his 1970 book, Reich laid it on the line: “The great error of our times has been the belief in structural or institutional solutions. The enemy is within each of us; so long as that is true, one structure is as bad as another.” And Reich added a fanciful theory of “liberation” that would leave behind the corporate liberal constraints of the era.

Liberation, he wrote, “comes into being the moment the individual frees himself from automatic acceptance of the imperatives of society and the false consciousness which society imposes.” His optimism sprang from the belief that “the whole Corporate State rests upon nothing but consciousness. When consciousness changes, its soldiers will refuse to fight, its police will rebel, its bureaucrats will stop their work, its jailers will open the bars. Nothing can stop the power of consciousness.”

Fast forward a quarter century.

In 1995, the same Charles Reich was out with another book — Opposing the System — his first in two decades. Gone were the claims that meaningful structural change would come only as a final step after people got their heads and culture together. Instead, the book focused on the melded power of huge corporations and the U.S. government.

Reich’s new book was as ignored as “The Greening of America” had been ballyhooed; no high-profile excerpt in The New Yorker or any other magazine, scant publicity, and not even faint controversy. Few media outlets bothered to review “Opposing the System.” A notable exception, the New York Times, trashed the book.

In his 1995 book, Reich challenged what he called “the System” — “a merger of governmental, corporate, and media power into a managerial entity more powerful by reason of technology, organization, and control of livelihood than any previously known form of rule.” Reich astutely noted that “we deny and repress the fact of corporate governmental power,” and he pointed out: “There will be no relief from either economic insecurity or human breakdown until we recognize that uncontrolled economic forces create conflict, not well-being.”

In sharp contrast to his flat assertion a quarter century earlier that “the whole Corporate State rests upon nothing but consciousness,” Reich now emphasized the egregious imbalances of financial power: “It is economic deprivation that comes first, dysfunctional behavior second, in the true cause-and-effect sequence.”

The author saw a much fuller social context for the yearning and euphoria that had animated “The Greening of America” and the era it celebrated to excess in 1970. Far wiser in 1995, he wrote: “Most of the important things in life, the things we truly desire, such as love, joy, and beauty, lie in a realm beyond the economic. What we do not recognize is how economics has become the destroyer of our hopes. It is economic tyranny that cuts off our view of a better future.”

Today, even more, we live in a time of economic tyranny. The mantra of “hope” has proven hollow when directed toward a political leader; some react to disappointment by pinning their hopes on individual consciousness or cultural transformations. But deep patterns of economic predation, ecological destruction and endless warfare cannot be effectively undermined by transcendent consciousness or cultural radicalism. Realistic hope is not in a political star or in the mere transformation of our individual selves. Our best strategies and our futures are bound together with political engagement that embraces all of humanity.

Norman Solomon

Norman Solomon

Norman Solomon is national co-chair of the Healthcare Not Warfare campaign, launched byProgressive Democrats of America. His books include “War Made Easy: How Presidents and Pundits Keep Spinning Us to Death.” For more information, go to: www.normansolomon.com

Book REVIEW / NONFICTION :

Fighting a New Bogyman--a Nameless, Faceless System :

OPPOSING THE SYSTEM by Charles A. Reich; Crown $23, 219 pages

JONATHAN KIRSCH SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

Charles Reich's "The Greening of America," first published in 1970, was one of those rare books that captured and helped to define the spirit of its times. The very word greening became a kind of shorthand for the boisterous but humane values of the late '60s and pre-Watergate '70s, and Reich was seen as a gleeful guru of revolution and redemption.

No such light escapes the black hole of Reich's new book, "Opposing the System." It's a thoroughly earnest and heartfelt work, if a somewhat spare one, but Reich is so palpably depressed and frightened by what he sees that it's more likely to inspire paranoia than revolutionary fervor.

Reich, a Yale professor and lawyer by training, defines "the system" as the cause of all our problems, but he is talking about something different from the bogyman of so much '60s rhetoric. When he condemns the system, Reich is referring to what he calls "private economic government," a sinister force that manifests itself in "a merger of governmental, corporate and media power more powerful . . . than any previously known form of rule."

Indeed, Reich begins to sound a bit like a character from a Philip K. Dick novel when he conjures up a world in which faceless corporate minions driven by pure and impersonal greed make the only decisions that really count.

"The invisible system that governs us has no name," he writes. "It has circumvented the Constitution, nullified democracy, and overridden the free market. It usurps our powers and dominates our lives. Yet we cannot see it or describe it. It is new to human history."

Only rarely does Reich step down from his soapbox and speak in concrete terms--and only then do we begin to understand what he is so worked up about. He insists that "big government" and the "free market" and the "welfare state" are mostly myths; the real power, and thus the real problem, can be found in the boardrooms and corner offices of corporate America.

"Private economic government is a far more important factor in the lives of individuals than public government," he writes. "In order to get a job, have a career, escape the abyss of being rejected or discarded, people will accept the dictates of corporate and institutional employers, even when these dictates go far beyond anything that public government could constitutionally impose."

An employee who is desperate to get or keep a job, Reich points out, will submit to drug-testing, workplace surveillance, personal searches and censorship by the employer, all of which would be illegal if carried out by the government.

"Economic coercion," he quips, "is violence in slow motion."

Reich specifically calls for a revival of the spirit of protest that characterized the '60s as a way to "fight the system," a phrase that summons up the crackling but directionless energy of the very era in which "The Greening of America" was a bestseller.

"The next stage of this drama must inevitably be the return of protest, of demonstrations and direct action," Reich exhorts. "But this time, protest must find a way to be effective, to unite rather than divide, and to achieve a change of direction."

Reich insists that we need "a new map of reality," and he boldly takes it upon himself to give us one in "Opposing the System." And yet Reich despairs over the loss of vision that once prompted us to feel so optimistic in the '60s. "We are all stumbling in the dark," he broods. "We have lost the ability to imagine a better future."

There's an irony at work in Reich's book. Precisely because so many Americans feel overwhelmed by the system, so frustrated at the impotence of our democracy, so uncertain about which way to jump, it's hard to imagine that Reich's book will prompt the populace to take to the streets in a stirring show of unity.

Reich calls on us to "fulfill our duty as human beings to choose the upward path." But I could not help but feel that the reader who will respond most powerfully to Reich's description of a vast conspiratorial machine that runs our lives is more likely to think in terms of train derailments and the bombings of government buildings than in peace marches and love-ins.

JONATHAN KIRSCH SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

Charles Reich's "The Greening of America," first published in 1970, was one of those rare books that captured and helped to define the spirit of its times. The very word greening became a kind of shorthand for the boisterous but humane values of the late '60s and pre-Watergate '70s, and Reich was seen as a gleeful guru of revolution and redemption.

No such light escapes the black hole of Reich's new book, "Opposing the System." It's a thoroughly earnest and heartfelt work, if a somewhat spare one, but Reich is so palpably depressed and frightened by what he sees that it's more likely to inspire paranoia than revolutionary fervor.

Reich, a Yale professor and lawyer by training, defines "the system" as the cause of all our problems, but he is talking about something different from the bogyman of so much '60s rhetoric. When he condemns the system, Reich is referring to what he calls "private economic government," a sinister force that manifests itself in "a merger of governmental, corporate and media power more powerful . . . than any previously known form of rule."

Indeed, Reich begins to sound a bit like a character from a Philip K. Dick novel when he conjures up a world in which faceless corporate minions driven by pure and impersonal greed make the only decisions that really count.

"The invisible system that governs us has no name," he writes. "It has circumvented the Constitution, nullified democracy, and overridden the free market. It usurps our powers and dominates our lives. Yet we cannot see it or describe it. It is new to human history."

Only rarely does Reich step down from his soapbox and speak in concrete terms--and only then do we begin to understand what he is so worked up about. He insists that "big government" and the "free market" and the "welfare state" are mostly myths; the real power, and thus the real problem, can be found in the boardrooms and corner offices of corporate America.

"Private economic government is a far more important factor in the lives of individuals than public government," he writes. "In order to get a job, have a career, escape the abyss of being rejected or discarded, people will accept the dictates of corporate and institutional employers, even when these dictates go far beyond anything that public government could constitutionally impose."

An employee who is desperate to get or keep a job, Reich points out, will submit to drug-testing, workplace surveillance, personal searches and censorship by the employer, all of which would be illegal if carried out by the government.

"Economic coercion," he quips, "is violence in slow motion."

Reich specifically calls for a revival of the spirit of protest that characterized the '60s as a way to "fight the system," a phrase that summons up the crackling but directionless energy of the very era in which "The Greening of America" was a bestseller.

"The next stage of this drama must inevitably be the return of protest, of demonstrations and direct action," Reich exhorts. "But this time, protest must find a way to be effective, to unite rather than divide, and to achieve a change of direction."

Reich insists that we need "a new map of reality," and he boldly takes it upon himself to give us one in "Opposing the System." And yet Reich despairs over the loss of vision that once prompted us to feel so optimistic in the '60s. "We are all stumbling in the dark," he broods. "We have lost the ability to imagine a better future."

There's an irony at work in Reich's book. Precisely because so many Americans feel overwhelmed by the system, so frustrated at the impotence of our democracy, so uncertain about which way to jump, it's hard to imagine that Reich's book will prompt the populace to take to the streets in a stirring show of unity.

Reich calls on us to "fulfill our duty as human beings to choose the upward path." But I could not help but feel that the reader who will respond most powerfully to Reich's description of a vast conspiratorial machine that runs our lives is more likely to think in terms of train derailments and the bombings of government buildings than in peace marches and love-ins.

2 comments:

Thanks for share this information

good morning images

Are you looking for cctv camera for your office or home then you have reached the perfect place. Cctv camera Mumbai offer you highest quality products which ensure the durability and expert after sales services which ensure smooth running of your electronic security system. We deals in all major brands like hikvision, cp plus, dahua. We offer you best cctv camera price in Mumbai to setup cctv camera at your office of home you can contact us on

CCTV CAMERA DEALERS IN MUMBAI

Address: D/3, Sai Dham Niwas, Sai Nagar Road, near Sai Mandir, Bhandup East, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400042

Phone: 090043 43144

Post a Comment