The 'pro-life' term was once a moral call to arms, but it has become a mere political checkbox

.

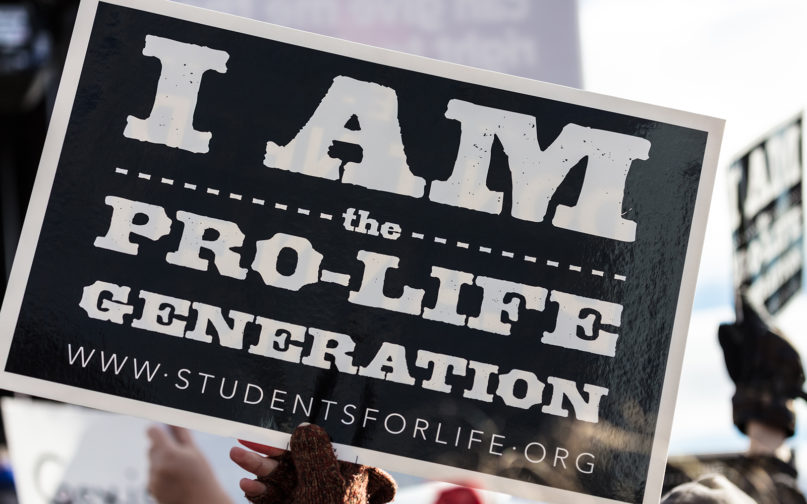

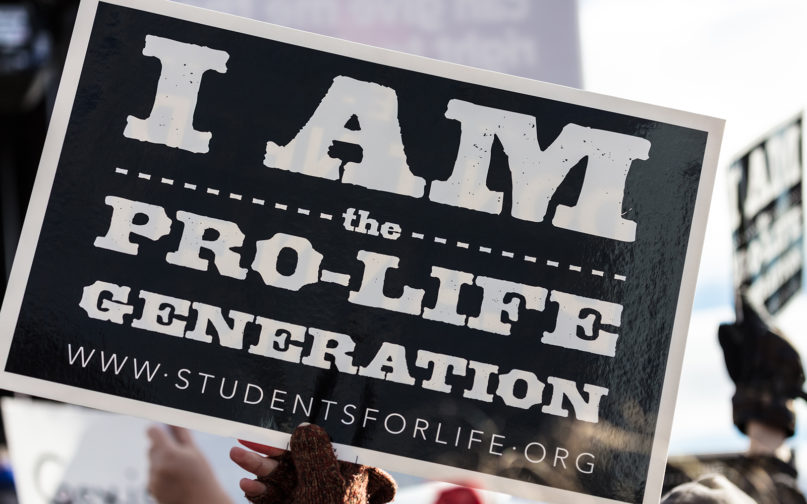

A sign held during the 2017 March for Life in Washington.

A sign held during the 2017 March for Life in Washington.

Photo by James McNellis/Creative Commons

November 2, 2020

By Jonathan Merritt

(RNS) — Sister Mary Traupman is a staunchly pro-life Roman Catholic nun, but she’s casting her vote for pro-choice Democrats and Joe Biden in this election — because of her pro-life convictions, not in spite of them.

In a recent letter to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Traupman argued that being pro-life must expand to include “the lives of those already born,” including migrants, poor people, the elderly, trafficking survivors and victims of racism.

Of Trump’s record she wrote, “Ripping born babies from their mothers’ arms, lifting regulations to preserve our environment for future generations, implementing tax cuts to benefit only a segment of our society, ignoring a health threat to hundreds of thousands of lives, robbing the poor of health care … these are not pro-life policies.”

Traupman’s defection may strike some as contradictory, but her logic is increasingly common among a chorus of pro-lifers who say they have awoken to the way conservative activists have transformed abortion into a single-issue trump card that renders other life-and-death matters irrelevant.

They are championing human flourishing “from the womb to the tomb” and are ready to take back the “pro-life” label from anti-abortion activists.

RELATED: Abortion over immigration: Trump’s pro-life policies remain paramount for many Latino Catholics

In his 2016 book “Defenders of the Unborn,” historian Daniel Williams traces the birth of the American pro-life movement to the 1930s and ’40s, when physician-led groups began arguing for the repeal of abortion laws. At the time, resistance was largely limited to Catholic political advocacy groups.

But in the 1960s, anti-abortion advocates searched for a banner capacious enough to mainstream the movement and powerful enough to polarize the electorate. They settled on “pro-life,” a term considered by many to be a “marketing masterstroke.” The term cloaked the movement with gleaming positivity, yoked it with moral heft and reframed its opposition as affirmative.

As Quartz’s Annalisa Merelli recently wrote, “The success of the label is largely due to its ability to frame the issue not as standing against something (a woman’s choice) but in favor of it (life).”

The new definition of “life” not only stuck, it spread. Soon, phrases like “the sanctity of life” and “right to life” flooded the public square, and the movement’s ranks swelled.

Before this rebrand, many social conservatives, and even a sizable portion of evangelical Christians, supported abortion rights, believing that human life began at birth rather than conception.

The Southern Baptist Convention passed resolutions in 1971, 1974 and 1976 affirming a woman’s right to choose to protect her physical or even emotional wellbeing. But in time, the new label persuaded evangelicals, Mormons and other social conservatives that opposition to abortion was not just important, but the most important moral issue of the day.

As a political issue, abortion did not break neatly across party lines during most of the 20th century. As Williams noted, “Prior to the mid-1970s, no one would have associated the GOP with opposition to abortion.”

The rhetorical move was so effective that it left progressives scrambling to find their own label. They settled on “pro-choice,” an inferior brand that lacks the emotion of “pro-life.”

Yet “pro-life” had its own problems. Pro-choicers claimed the label truncated the range of its core concern — human life — to legal protections for the unborn. Barnett “Barney” Frank, the Massachusetts congressman, was not completely off-base when he quipped in 1981 that pro-lifers believe “life begins at conception and ends at birth.”

These days, some pro-lifers are awakening to the truth behind Frank’s barb.

The Rev. James Martin, a prominent Jesuit priest and bestselling author (and a friend), has written that he “cannot deny that I see a child in the womb, from the moment of his or her conception, as a creation of God, deserving of our respect, protection and love.” But he believes that the same vision — and the same advocacy — should apply to at-risk LGBTQ youth, inmates on death row, refugees seeking asylum and impoverished and homeless people, for whom protection rarely appears on pro-lifers’ political punch list.

In a recent YouTube video, Martin said, “The problem with the term ‘pro-life’ is that it’s often used just to talk about the unborn, but pro-life means being pro-all lives, not just pro-some lives, because all lives are sacred.”

Once upon a time, public comments like these might land a Catholic priest or nun in hot water, but Martin gets by with a little help from his friends in the Vatican. In Pope Francis’ 2015 speech to the U.S. Congress, the pontiff said that Christians have a “responsibility to protect and defend human life at every stage of its development.”

The “pro-life” term that once so deftly reframed the abortion debate, in short, has now become its Achilles heel. It threatens to splinter a movement that has remained remarkably unified for nearly half a century.

The “pro-life” term was once a moral call to arms, but it’s now a mere political checkbox. Opposition to abortion is a non-negotiable for many conservatives, and a number of evangelical friends proudly admit to being “single-issue voters” who support only pro-life candidates. Other moral and political positions don’t factor into their decisions.

This faulty political ideology ignores, trivializes and even disregards dozens of issues of profound human consequence, such as police brutality, environmental degradation, state-sanctioned torture, unjust wars, alleviation of poverty and the mistreatment of minority groups.

Lately, some prominent evangelicals are reclaiming the pro-life label. In 2016, evangelical theologian and author Ron Sider penned an article in the Christian magazine Plough, arguing that the Bible’s political vision is “completely pro-life,” acknowledging that children are persons “from the moment of conception,” but it also points to “other ways that human lives are destroyed.

“Why, I wondered, did many pro-life leaders fail to support programs designed to reduce starvation among the world’s children?” Sider asked. “Why did others oppose government funding for research into a cure for AIDS? Why did an important pro-life senator fight to save unborn babies only to defend government subsidies for tobacco products, which cause six million deaths around the globe each year?”

Sider said pro-lifers should reject single-issue voting and instead weigh a candidate’s position on matters such as capital punishment, racism, environmental degradation and global poverty, as well as abortion. That same year, Sider proclaimed in Christianity Today that he would be voting for Hillary Clinton, even though he had not publicly endorsed a political candidate in 44 years.

Just this month, Sider joined an impressive collection of prominent Christian leaders to launch “Pro-life Evangelicals for Biden.” Their mission statement is a concise two-sentence summary that claps with moral thunder: “As pro-life evangelicals, we disagree with Vice President Biden and the Democratic platform on the issue of abortion. But we believe a biblically shaped commitment to the sanctity of human life compels us to a consistent ethic of life that affirms the sanctity of human life from beginning to end.”

Another co-founder of the group, former evangelical megachurch pastor Joel Hunter, said that he and other members oppose abortion as vehemently as ever, but, “We want to make sure the pro-life agenda is expanded beyond birth.”

Hunter also noted that overturning Roe v. Wade, long a goal of the pro-life movement, will only serve to return America to a dark past when women sought out and sometimes died from self-induced and black-market abortions. Instead, he said, pro-lifers should focus on reducing the occurrence of abortion by reducing the perceived need for them.

This can be accomplished through more access to contraception, tax credits for adoption, increased funding for low-income women who wish to bring their children to term and comprehensive sexual education. Conservatives shy away from this “abortion reduction agenda,” but some Democrats don’t: the strategy was once championed by President Barack Obama.

RELATED: What does the Bible really say about abortion?

I am a churchgoing Christian who graduated from Liberty University and an evangelical seminary. I was raised by a megachurch pastor and former president of the Southern Baptist Convention who proudly describes himself politically as “to the right of Ronald Reagan.”

My mother, whom I love dearly and respect deeply, has been a stalwart Trump supporter since the famous escalator moment at Trump Tower. I’ve voted almost exclusively for Republican candidates in federal elections ever since I turned 18, and I still consider myself “pro-life.”

But these days my pro-life convictions are leading me to vote mostly for Democrats.

I have come to agree with Sister Joan Chittister, the Catholic nun and peace activist, who recently said, “I do not believe that just because you are opposed to abortion that makes you pro-life. In fact, I think in many cases, your morality is deeply lacking if all you want is a child born but not a child fed, not a child educated, not a child housed.”

Chittister’s coup de grace handily exploits conservatives’ shortcomings, arguing they are often not pro-life, but “pro-birth.” Some may dismiss witticisms like this as a tiny crack in the movement’s dam, but the fracture looks mightier than ever, and water is leaking.

If the Republican Party follows its path of platforming pro-life candidates who show little regard for post-birth life, the dribble may become a deluge that could sweep away one of the most powerful political movements of the last half-century.

No comments:

Post a Comment