“It used to be Southerners didn't want Blacks to vote because they're Black. Now they don’t want them to vote because they're Democrats.”

Emmanuel FeltonBuzzFeed News Reporter

Posted on November 2, 2020

Barbara Gauntt / Reuters

A campaign rally for Democratic Senate candidate Mike Espy in Jackson, Mississippi, Sept. 3, 2020.

Black Mississippians who go to the polls Tuesday will likely be waiting in long lines, and potentially be exposed to a lethal virus that has disproportionately hurt their communities, after state Republicans refused to loosen voting restrictions in the midst of the pandemic.

There’s a lot more on the ballot than just the presidential election: The people of Mississippi will be deciding between a sitting Republican senator with a history of racist remarks and a former US secretary of agriculture who would be the first Black senator from Mississippi since Reconstruction.

They will be deciding whether to replace a confederate symbol on the state flag.

And they will vote on the fate of a Jim Crow–era law that effectively makes it impossible for a Black person to win statewide office, because it requires governors and other state leaders to win a majority of the statewide vote as well as secure the most votes in a majority of 122 state House districts.

Local election officials are predicting record turnout and long lines across Mississippi on Election Day, in the only state nationwide where lawmakers didn’t give citizens either the option to vote early in person or to mail in a ballot during the COVID-19 pandemic. The legislature only expanded early voting to people who were under physician-order quarantine — which some officials say requires a doctor’s note — or who were taking care of someone in quarantine.

“It's already a lot busier,” said Jackie Jackson, deputy circuit clerk in Jefferson County, who said, even under the state’s strict rules, the county had already been seeing more absentee voters turn up at their office than she can remember over her over 20 years working there. “It’s probably going to be the busiest Election Day I've at least seen.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Some voting rights advocates are worried that amid a new surge in coronavirus cases, Black Mississippians in particular will have to decide between risking their health and exercising their right to vote.

Over 1,300 Black people in the state have died from COVID-19 so far, and while there has been a recent spike in deaths among white Mississippians, Black residents are still 2.5 times more likely to die of the disease.

Mississippi’s voting laws have long been among the most restrictive in the nation with few expansions to access since the Voting Rights Act of 1965 but additional restrictions like a new voter ID law in 2014. Unlike in many other states, Republican leaders made little effort to expand voting access in light of the extraordinary concerns over health and safety during the pandemic. In a pair of lawsuits, advocates pushed for broader exemptions but were largely unsuccessful.

“It used to be Southerners didn't want Blacks to vote because they're Black. Now they don’t want them to vote because they're Democrats,” said Robert Howard, a political science professor at Georgia State University who studies Southern politics.

He added that it’s hard to disentangle any decisions on voting procedures from issues of race in the South.

In September, the Mississippi Supreme Court reversed a lower court decision and ruled that people with medical conditions that put them at higher risk of severe complications from COVID-19 were not automatically entitled to an absentee ballot. That was after Republican Secretary of State Michael Watson appealed a state court’s decision approving the protections.

State law does allow Mississippians with disabilities to vote early — but Robert McDuff, the civil rights lawyer pushing for expanded protections in the case, said the Supreme Court’s decision leaves it open to county clerks to decide who does and doesn't qualify as having a temporary disability during the pandemic.

Rogelio V. Solis / AP

A woman in a face mask walks past a sign encouraging voters to vote absentee in light of COVID-19 precautions on the grounds of the Hinds County Courthouse in Jackson, Mississippi, Oct. 6, 2020.

As of Oct. 25, the last time Watson issued an update, over 142,591 Mississippians had voted early. That’s a record for the state, but Mississippians have cast just 12% of the total number of ballots in 2016. As of Sunday, voters nationally have cast over two-thirds of the total number of ballots cast in 2016. In nearby states with more robust early voting laws like Tennessee, Georgia, and Florida, voters have already cast over 80% of the total ballots they cast in the last presidential election. Texas surpassed its total number of votes cast in 2016 by the time early voting closed on Friday.

Given how much harder Black communities in the state have been hit by COVID-19, voting rights activists say the state’s lack of accommodations for the pandemic is just the latest in a long line of efforts to suppress the votes of the Black community.

Mississippi has among the most racially polarized electorates in the country. Black Mississippians overwhelmingly vote for Black politicians and Democrats, while the vast majority of white voters there vote for white Republican candidates. And like elsewhere in the country, masks have become wrapped up in politics.

“The Republicans perceived that it would be in their political interest to discourage people from voting,” said McDuff. “Particularly low-income people, particularly people who would be following public health guidelines more strictly, because those people are perceived to be Democrats not Republicans, generally speaking.”

While the state’s first wave hit its Black community hardest, as the election approaches, Mississippi is experiencing a second wave of coronavirus cases fueled by white Mississippians who refuse to wear masks, said Dr. Thomas Dobbs, the top health officer in Mississippi.

“We have had really pretty good uptake by a lot of folks in the Black community with masking and social distancing,” Dobbs said on a call with reporters. “And I just want to say that I think big parts of the white community, especially in areas that maybe weren’t as hard-affected [this summer], have not been as compliant or engaged actively with social distancing and masking. And I think that does make a difference.”

Republican Gov. Tate Reeves let the statewide mask order expire at the end of September, but county clerks are assuring voters that polling locations will be safe. Under regulations handed down by the secretary of state, poll workers, poll watchers, and elected officials must wear masks in the precinct. Voters, however, won’t be turned away if they refuse to wear a mask.

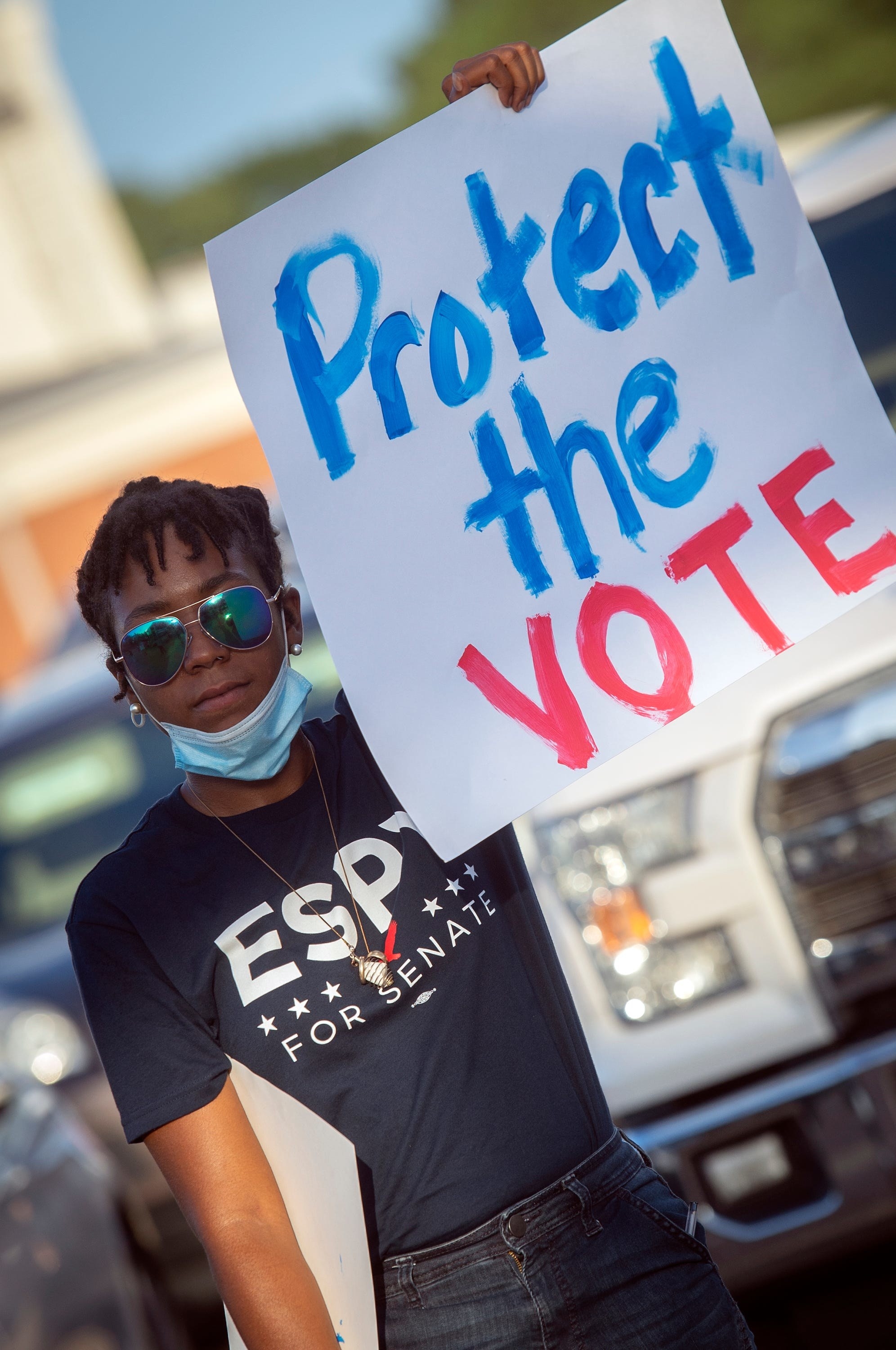

Barbara Gauntt / Reuters

An Espy supporter at a drive-in style campaign rally in Jackson, Mississippi, Sept. 3, 2020.Voting rights advocates like Oleta Fitzgerald, director of the Children’s Defense Fund’s southern regional office, are worried about unmasked white voters showing up at the polls and intimidating Black voters.

"They know the population most at risk are people of color, and so not expanding early and absentee voting during this pandemic was a backdoor way of trying to decrease turnout,” said Fitzgerald.

Even with limited early voting, long lines have already been reported at the circuit clerk’s office in Hinds County, the most populous county in the state and a Democratic stronghold, where a record 13,000 absentee ballots have been cast. That picture differs across the state. In counties where Black and white voters are more evenly split and Republicans have control of the county clerk’s office, there have been far fewer absentee ballots cast. Part of the concern for advocates is that so much is left up to how accommodating county clerks want to be to voters concerned about COVID-19.

Fitzgerald is worried about places like Jones County, where election commissioner Gail Welch posted on social media earlier this year to warn about an increase in Black voter registration there in the wake of the effort to remove the Confederate symbol from the state flag.

“The blacks are having lots [of] events for voter registration. People in Mississippi have to get involved, too,” she wrote on Facebook.

“So far, we've seen county clerks in majority Black counties are being a lot more lenient with how they read the rules related to the COVID, they're also allowing some leniency in terms of the fear that you've got some other kind of health issues,” said Fitzgerald.

“Right now, what I’m concerned about is voter protection on Election Day. We have a number of counties that are majority white but have large Black communities. There’s where we’re concerned that there might be some efforts to intimidate those folks on Election Day. So the poll monitoring, poll watching all of that is more critical than ever, especially with all the dog whistles that have gone off this year,” she said, referring to President Donald Trump’s campaign rhetoric.

Others are more hopeful that despite the challenges, the system will work for voters in Mississippi tomorrow.

“Mississippi is a horrible place to try to vote in, but I think that our circuit clerks and our election commissions are doing everything that they possibly can,” said Christy Wheeler, co-president of the Mississippi League of Women Voters. “I think that we will see a huge turnout and that we may have lines, but I absolutely believe that because if they show up by 7 p.m., even though there might be long lines, they'll get the opportunity to vote.”

Voters will be deciding whether to reelect Republican Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, who gathered national headlines in 2018 when she said of a supporter, “If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.”

Rogelio V. Solis / AP

Incumbent Republican US Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith gestures as she speaks at a campaign stop at the Richland, Mississippi, City Hall, Oct. 29, 2020.

Around the same time, CNN dug up 2014 photos from her Facebook page, in which she is posing in a Confederate soldier hat with an old Civil War rifle in hand; she captioned the photo, “Mississippi history at its best!” Hyde-Smith defeated her Black Democratic opponent Mike Espy by 7 points in a 2018 special election.

The two are set for a rematch on Tuesday. There have been few polls in the race, though one last week showed Hyde-Smith up by 8 points. Espy, for his part, has said the election will come down to Black turnout and he's hoping for that to be higher than the previous records set when President Barack Obama was on the ballot.

In the same poll that had Espy down by 8 points, 61% of voters supported changing the state flag and a small majority supported repealing the law requiring statewide candidates to win in a majority of the 122 state house districts. Opponents of that law say it dilutes the Black vote and makes it all but impossible to elect a Black candidate to statewide office since the candidate would also have to secure support in heavily white communities.

“Justice is on the ballot,” said Fitzgerald. “Safe and healthy schools are on the ballot. Childcare and healthcare are on the ballot. Financial support for small businesses that are being left is on the ballot. And then we say, Jim Crow is on the ballot.”

Arekia Bennett, executive director of the nonpartisan Mississippi Votes, said she knows that voters will be facing even more challenges than usual this year, but she’s hopeful Mississippians won’t be deterred, given everything that’s at stake.

“We've got the senatorial race, we've got folks running for our supreme court, and we also have three ballot measures,” said Bennett. “There's one to remove the 1890 Jim Crow law. We get to vote for the flag, and we get to vote for or against the usage of medical marijuana. We need people to show up and make their voices heard like never before here, because we've got an opportunity of a lifetime to make some drastic changes.”

Emmanuel Felton is an investigative reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment