The invisible shield: how qualified immunity was created and nearly destroyed the ability to sue police officers in America Pt. I

HERB BOYD and DAMASO REYES | 4/1/2021, midnight

In the aftermath of the Civil War an America broken by bloodshed and riven by racial strife began slowly putting itself back together. In little more than five years a nation that had been founded on chattel slavery passed the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, bringing the country to the precipice of being able to, for the first time in its history, live up to those famous words in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.” In the South, where the memories of slave auctions were still fresh, Black men were elected and appointed to state legislatures, the House of Representatives and the United States Senate. America, it seemed, was changing.

But the true believers in the “Lost Cause” would not, or could not, accept this. Throughout the country, but especially in the South, justice was denied to Black Americans despite the new protections enshrined in the Constitution. The KKK was formed and often local members and government officials were one and the same. And they used their official positions to mete out their own brand of justice when they couldn’t use a rope and a tree.

It was in this context that the Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, was passed. It stated very clearly, “Every person who, under color of any statute…subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law.” (Emphasis added.)

Put simply, government officials who violate the constitutional rights of citizens or anyone else in the United States while performing their official duties can be sued by that person. As Reconstruction ended, this ability to sue was essential to provide at least civil relief to the victims of those who would misuse their offices but were rarely held accountable. But over the course of the 20th century this very clear statute was redefined and reinterpreted not by Congress which passed it but by unelected judges who twisted its meaning into the doctrine we now know as qualified immunity.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” the novelist William Faulkner wrote. And those words are given fresh currency in two instances that set the course of creating the concept of qualified immunity as we know it. These cases allowed a law designed to protect Americans, especially Black Americans, against the misuse of official power to instead become a shield for government officials, especially law enforcement.

In order to understand where we are today we must travel back to September 1961.

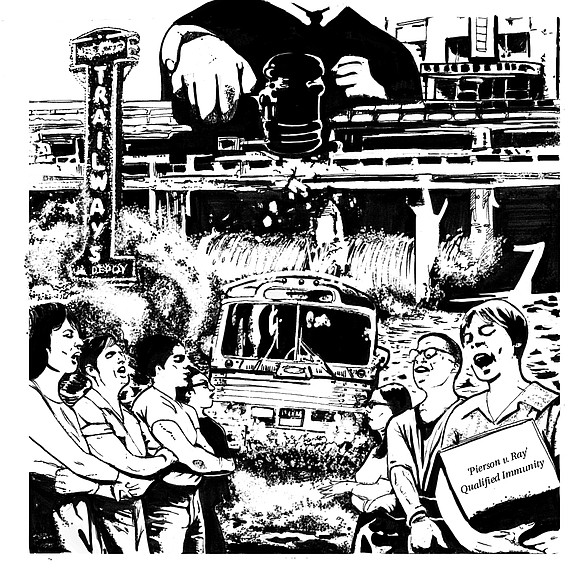

Freedom Riders lose the freedom to sue

At that time the Rev. Robert L. Pierson was traveling with a delegation of priests as part of the Mississippi Freedom Rides when he was arrested, along with 14 others—three of them Black—for a “breach of peace,” a Mississippi statutory code violation.

The interracial group, bound for Chattanooga, Tennessee, was arrested in a coffee shop in a Trailways bus terminal in Jackson, Mississippi. They faced a misdemeanor charge after refusing to move on when ordered to do so by police officers. Local judge James Spencer found them guilty and sentenced them to four months and a $200 fine and, according to several published accounts, the judge and the captain had arrested and sentenced countless Freedom Riders on similar “breach of peace” charges. The clerics were soon out on bail, filed an appeal, and exhaled when the case was dismissed on a directed verdict. Judge Russell Moore concluded there was no violation of the law.

Believing they were falsely arrested and imprisoned, the priests sought damages in the Jackson district court. The jury in the case found in favor of the police, who had asserted they were merely acting to prevent violence. The priests took their case to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit where they also found no redress. The Appeals Court ruled that Judge Spencer could not be held liable for his decision, even though the Court also ruled that the Mississippi law the priests had been convicted under was unconstitutional. It was their opinion that the law does not require the officers “to predict at their peril which state laws are constitutional and which are not.” This was the first crack in the dam that would unleash qualified immunity.

Finally the plaintiffs reached the Supreme Court. The defendants were captain J.L. Ray, the police chief; the two arresting officers David Allison Nichols and Joseph David Griffith; and Judge Spencer, the municipal police justice who had originally convicted the priests.

At the core of Pierson v. Ray was the issue of whether the Civil Rights Act of 1871 truly guaranteed citizens the ability to sue any government official who caused a deprivation of rights under the Constitution. Eight of the nine of the Supreme Court Justices affirmed the lower court’s ruling that Judge Spencer could not be held liable for damages under the Civil Rights Act of 1871, extending a long-standing legal principle that judges are immune from lawsuits for damages, established in Bradley v. Fisher (1872). Moreover, the majority added that while the police officers who arrested the priests did not have total immunity from lawsuits, they did have protection in the same way that an officer who unknowingly arrests an innocent person based on probable cause is not guilty of false arrest.

With the Pierson v. Ray case in 1967, the Supreme Court extended a “good faith defense” to police officers. This protected police officers, judges and other government officials who made good faith errors from being sued, an exception not provided by the Civil Rights Act of 1871. Despite this exception government officials who acted in bad faith were not protected by qualified immunity, for the moment.

But less than 20 years later the Supreme Court’s Harlow v. Fitzgerald decision in 1982 allowed the “good faith defense” to morph into what is now called qualified immunity and later deemed distinct from absolute immunity.

The dam breaks

Arthur Ernest Fitzgerald was a deputy for management systems in the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force. When he discovered $2 billion in cost overruns and technical problems in the Lockheed C5 program that had been concealed by Pentagon officials, he revealed it during his testimony before the Joint Economic Committee in Congress. For this, Fitzgerald claimed in his suit that he was blacklisted, denied any further roles of significance, and mentioned in the Watergate tapes by President Nixon, who took responsibility for firing Fitzgerald.

In response, Fitzgerald filed a lawsuit against government officials in 1969, charging he lost his job because he was a whistleblower. All of the Pentagon officials involved claimed absolute immunity, including Nixon and a few of his aides. Nixon, as president, was found to have absolute immunity; the Harlow v. Fitzgerald case examined whether the same immunity extended to his aides. While denying Nixon’s aides absolute immunity it did provide them with qualified immunity from lawsuits. With Harlow v. Fitzgerald qualified immunity became a kind of legal shield for government officials, who while “performing discretionary functions,” are “generally shielded from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate… clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known,” according to the Supreme Court ruling.

The term “clearly established” would be pivotal to the future of qualified immunity. It said, in essence, that unless a previous court ruling had clearly established a type of abuse which was unconstitutional, then the government official could be protected under qualified immunity.

“Fifteen years later in the early ’80s, the court stripped out the bad faith part of it, so it was no longer a question of whether the officer was acting in bad faith,” stated Scott Michelman, legal director of the ACLU of Washington, D.C. “The officer could be acting in bad faith and still, if the court found that the officer’s mistake about the Constitution was reasonable, the officer would still get immunity.”

Flood damage

“That was a major shift in the doctrine because what it meant was, even if its officer subjectively acted in bad faith, intentionally violated someone’s rights, they may be protected by qualified immunity, so at that point it no longer becomes a doctrine about protecting the officer who acted in good faith, as the court had initially said,” Amir Ali, deputy director of the Supreme Court and Appellate Program at the MacArthur Justice Center, said in an interview. Over the course of 100 years America went from a law that clearly allowed any government official to be sued by someone whom they deprived of their constitutional rights, to a system where police officers who were acting in good faith were protected against being sued to finally a system that by default protects police officers, even when it is clear they were acting in bad faith.

“It denies people whose constitutional rights have been violated an opportunity to bring their claims in a civil rights case, which is often the only available path toward justice for people whose rights have been violated,” Joanna C. Schwartz, professor of law at the UCLA School of Law, said of qualified immunity. “The doctrine makes bringing these claims much more expensive and complicated and time-consuming than they would be without it, which means that lawyers are less likely to bring these cases, which is another reason that people are denied justice when their rights have been violated.”

Since the Harlow decision the Supreme Court has expanded the reach of qualified immunity in a way that some say has emboldened police officers to violate people’s rights.

“The decisions themselves send a very dangerous message to police. As Justice Sotomayor said in an opinion, it suggests that police can shoot first and think later. The doctrine makes it harder for courts to explain what the Constitution requires and so creates more confusion than there would be otherwise about constitutional protections, which means that police departments can’t write policies and train their officers in compliance with the Constitution,” Professor Schwartz added.

In our next articles we will learn exactly how this judicially created doctrine has been used to protect law enforcement and why, as Amir Ali says, “Qualified immunity really eliminates the individual’s ability to hold law enforcement and correctional officials accountable.”

This series was made possible by grants from the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Solutions Journalism Network.

FOR PART II GO HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment