New book reveals extent of the musician’s fascination with scriptures of Judaism and Christianity

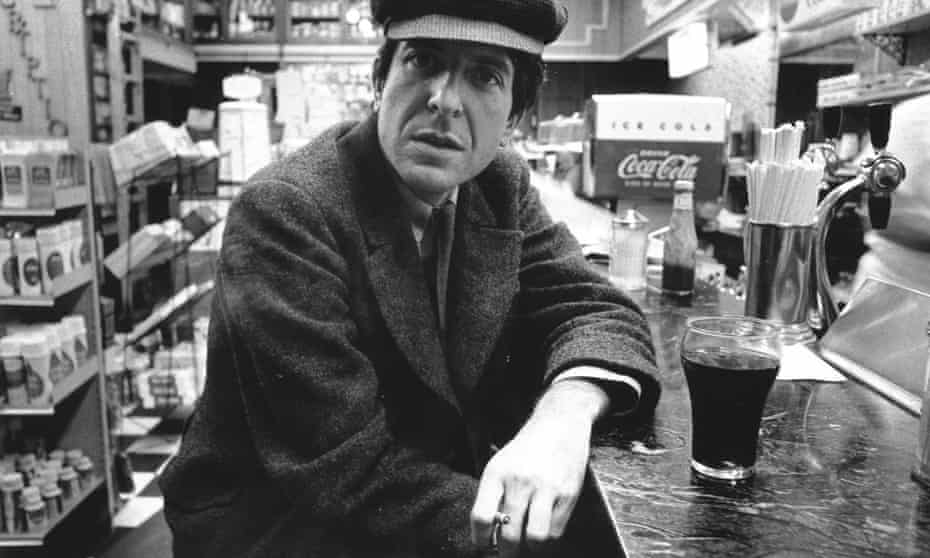

Leonard Cohen in New York in 1968. He was deeply learned about Judaism and Christianity. Photograph: Roz Kelly/Getty

Donna Ferguson

Donna Ferguson

BBC

Sun 17 Oct 2021

“She tied you to a kitchen chair, she broke your throne and she cut your hair, and from your lips she drew the Hallelujah...” No one hearing these lyrics from the song Hallelujah could doubt that Leonard Cohen knew how to write and sing about love, sex and desire. But fans of his music could be forgiven for not realising exactly what he was trying to convey about religion and the intricate references he was making to biblical stories, Talmudic legends and the Mishnah, a third-century Jewish text.

Now, an analysis of Cohen’s work sets out to reveal how extensively the revered songwriter used both Christian and Jewish stories and imagery to express ideas in his songs.

The book, Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots of Genius, explores the many different spiritual sources and the religious folklore the musician was drawing upon when he wrote masterpieces like Hallelujah, Suzanne and So Long, Marianne.

Sun 17 Oct 2021

“She tied you to a kitchen chair, she broke your throne and she cut your hair, and from your lips she drew the Hallelujah...” No one hearing these lyrics from the song Hallelujah could doubt that Leonard Cohen knew how to write and sing about love, sex and desire. But fans of his music could be forgiven for not realising exactly what he was trying to convey about religion and the intricate references he was making to biblical stories, Talmudic legends and the Mishnah, a third-century Jewish text.

Now, an analysis of Cohen’s work sets out to reveal how extensively the revered songwriter used both Christian and Jewish stories and imagery to express ideas in his songs.

The book, Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots of Genius, explores the many different spiritual sources and the religious folklore the musician was drawing upon when he wrote masterpieces like Hallelujah, Suzanne and So Long, Marianne.

Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots of Genius. Photograph: Bloomsbury

“I think he sees himself a little bit as a prophet,” says Harry Freedman, author of the forthcoming book, which will be published later this month, just before the fifth anniversary of Cohen’s death on 7 November. “He’s trying to elevate people’s thinking. Most rock music is about the world we live in. And I think he’s saying: there is stuff beyond that, think more deeply.”

Cohen, who was brought up in the Jewish faith, was “deeply learned” about both Judaism and Christianity.

“His lyrics are full of references to the Bible, the Talmud and Kabbalah [a Jewish mystical tradition with its roots in the late Middle Ages] but they are easily missed – he wove them so skilfully into his songs before reinterpreting them in completely new erotic, spiritual or mystical ways.”

In Hallelujah, for example, Cohen refers to the biblical story of King David who, according to Talmudic legend, delights angels and sages when he privately plays his harp at night. He is tested by God when – on his roof – he sees Bathsheba bathing. After committing adultery with her, David has her husband killed. “That leads to a series of disasters in David’s kingdom. There are rebellions against him, his son gets killed, his kingdom is broken – terrible things happen, because of the terrible things he did.”

Importantly, it is David who, according to ancient Jewish folklore, composed the Book of Psalms and invented the word “Hallelujah”, meaning “praise God”. “David is somebody who, like everybody, is sometimes good and sometimes bad. He’s trapped in the middle. And although he writes Hallelujah, which is a holy word, he’s also very, very broken.”

“I think he sees himself a little bit as a prophet,” says Harry Freedman, author of the forthcoming book, which will be published later this month, just before the fifth anniversary of Cohen’s death on 7 November. “He’s trying to elevate people’s thinking. Most rock music is about the world we live in. And I think he’s saying: there is stuff beyond that, think more deeply.”

Cohen, who was brought up in the Jewish faith, was “deeply learned” about both Judaism and Christianity.

“His lyrics are full of references to the Bible, the Talmud and Kabbalah [a Jewish mystical tradition with its roots in the late Middle Ages] but they are easily missed – he wove them so skilfully into his songs before reinterpreting them in completely new erotic, spiritual or mystical ways.”

In Hallelujah, for example, Cohen refers to the biblical story of King David who, according to Talmudic legend, delights angels and sages when he privately plays his harp at night. He is tested by God when – on his roof – he sees Bathsheba bathing. After committing adultery with her, David has her husband killed. “That leads to a series of disasters in David’s kingdom. There are rebellions against him, his son gets killed, his kingdom is broken – terrible things happen, because of the terrible things he did.”

Importantly, it is David who, according to ancient Jewish folklore, composed the Book of Psalms and invented the word “Hallelujah”, meaning “praise God”. “David is somebody who, like everybody, is sometimes good and sometimes bad. He’s trapped in the middle. And although he writes Hallelujah, which is a holy word, he’s also very, very broken.”

Most rock music is about the world we live in. I think he’s saying: there is stuff beyond that, think more deeplyHarry Freedman, author

There is a reference in the song to Samson, who loses his strength when his hair is cut by his lover Delilah, because – like Samson – David’s troubles begin when he can’t control himself around a woman. “I think Cohen is opening himself up in his songs. I think he’s trying to say: love can be wonderful. And love can be terrible. It can go horribly wrong and ruin your life.”

Cohen suffered from depression and, Freedman believes, would have identified strongly with David, a fellow musician. “David messed up. David’s kingdom was destroyed. And yet he sang Hallelujah. Because when you don’t know how to make sense of anything, when you’ve failed, when things go wrong, all you can do is sing Hallelujah. All you are left with is ‘praise God’. It’s a very religious idea.”

For Cohen, there is no conflict between popular culture and profound thinking, and no difference between Judaism and Christianity, says Freedman. “He sees them as all part of the same thing.” Sex and religion are also often closely intertwined in his songs: “In the Kabbalah, sex and procreation are holy acts. They symbolise the union of human and divine.” In one version of Hallelujah Cohen wrote, the narrator recalls: “I moved in you, and the holy dove she was moving too, and every single breath we drew was Hallelujah.”

Leonard Cohen in concert at the O2 Arena in London in 2013.

Photograph: Brian Rasic/Getty

Cohen, Freedman says, saw the imagery of religion as something he could use in lyrics to express himself and his unique, mystical way of looking at the world. “His vocabulary is one of religious myths and legends. This is what he knows and where he gets his metaphors from.” In Suzanne, for example, Cohen casually refers to an ancient Christian legend about Jesus rowing the apostle Andrew to a city, performing miracles and converting everyone from cannibalism to Christianity. “And that’s just in that one line in Suzanne: Jesus was a sailor when he walked upon the water.”

So Long, Marianne is one of the earliest songs Cohen wrote which has a mystical, spiritual element, Freedman says, and marks the beginning of the musician’s quest for spiritual meaning. “He sings ‘Come over to the window, my little darling. I’d like to try to read your palm.’ That’s probably the first time he mentions windows, which – later on in his work – are going to be a really important trope for him.” In Cohen’s work, a window is a liminal space, a place between two worlds or two states of being, he says. “He’s using the window to read her palm. He’s expressing something about destiny, about wanting to see what the future holds.”

When he tells Marianne that he forgot to pray for the angels, Freedman thinks he’s confessing that he has neglected his religious duties and spiritual side for her. “His love for Marianne has pushed everything else out. And maybe that’s one of the reasons he says ‘so long, Marianne’. It’s time we moved on. You’ve made me forget too much. And now I’ve got to get back to my spiritual core.”

Hallelujah: the first two verses

Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord

That David played, and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The minor falls, the major lifts

The baffled king composing Hallelujah.

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew her

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne, and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah

• Used with permission of the estate of Leonard Cohen

Cohen, Freedman says, saw the imagery of religion as something he could use in lyrics to express himself and his unique, mystical way of looking at the world. “His vocabulary is one of religious myths and legends. This is what he knows and where he gets his metaphors from.” In Suzanne, for example, Cohen casually refers to an ancient Christian legend about Jesus rowing the apostle Andrew to a city, performing miracles and converting everyone from cannibalism to Christianity. “And that’s just in that one line in Suzanne: Jesus was a sailor when he walked upon the water.”

So Long, Marianne is one of the earliest songs Cohen wrote which has a mystical, spiritual element, Freedman says, and marks the beginning of the musician’s quest for spiritual meaning. “He sings ‘Come over to the window, my little darling. I’d like to try to read your palm.’ That’s probably the first time he mentions windows, which – later on in his work – are going to be a really important trope for him.” In Cohen’s work, a window is a liminal space, a place between two worlds or two states of being, he says. “He’s using the window to read her palm. He’s expressing something about destiny, about wanting to see what the future holds.”

When he tells Marianne that he forgot to pray for the angels, Freedman thinks he’s confessing that he has neglected his religious duties and spiritual side for her. “His love for Marianne has pushed everything else out. And maybe that’s one of the reasons he says ‘so long, Marianne’. It’s time we moved on. You’ve made me forget too much. And now I’ve got to get back to my spiritual core.”

Hallelujah: the first two verses

Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord

That David played, and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth

The minor falls, the major lifts

The baffled king composing Hallelujah.

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Hallelujah, Hallelujah

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew her

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne, and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah

• Used with permission of the estate of Leonard Cohen

No comments:

Post a Comment