Releasing US$9.5 billion in frozen assets can’t help the Afghan people as long as the Taliban remain in power

December 16, 2021

THE CONVERSATION

Afghanistan is in a major humanitarian crisis: the health sector is failing, the economy is collapsing, and amid the COVID pandemic, famine is inflicting ever-larger numbers of casualties. According to the most recent report by the UN World Food Programme, more than half of the resident population of 38 million are facing acute hunger and 3.2 million children under five suffer from malnutrition.

Droughts, combined with the suspension of foreign aid in the aftermath of the Taliban’s takeover, have led to a dire economic situation, with recent reports indicating that some families in the northwest are selling their children out of desperation. Food and fuel prices are soaring.

On October 17, the Taliban foreign minister, Amir Khan Mottaqi, called on the US Congress to ease sanctions and release Afghanistan’s reserves. But would the US$9.5 billion (£7.16 billion) of frozen assets of Afghanistan Central Bank do anything to alleviate the deeply rooted poverty and food insecurity of the Afghan people – or will this only benefit the Taliban and its fighters?

Even in the near term, this amount of money will not go far to address poverty in Afghanistan. It has been estimated the reserves would cover the import costs of Afghanistan for only 15 months. The US-backed regime’s budget estimate for the fiscal year 2020 was $6.22 billion.

Join thousands of Canadians who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

The situation has been made worse by several other factors: drought, dependency on international aid and high unemployment rates. These extend far deeper and beyond the reach anything $9.5 billion could achieve. International aid made up about 75% of the US-backed regime’s budget. Afghanistan’s assets are only a fraction of the aid the country needs.

Skills deficit

It is naive to think that the Taliban’s caretaker cabinet and its civil service is able to administer these funds efficiently. The Taliban’s leadership lacks the knowledge, skill and experience needed to run state institutions and deliver services while managing an unfolding humanitarian crisis against the backdrop of a pandemic.

Political considerations

Finally, the release of Afghanistan’s foreign assets is tied to the question of the Taliban’s legitimacy. No government so far – including staunch supporter Pakistan – has officially recognised the Taliban’s government. Freezing Afghanistan’s assets was a political decision by US president Joe Biden to put pressure on the Taliban to form an inclusive government, so releasing these assets to the Taliban is akin to formal recognition of the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. Even if it was released for entirely humanitarian reasons, the Taliban would not hesitate to make this into a propaganda coup.

Economic sanctions have been effective in some regards. The Taliban is realising that its survival depends on changing its policies, both regarding women’s rights and forming an inclusive government. The opening of schools for girls in cities such as Herat and Mazar-e Sharif is indicative of the effectiveness of pressure put on the Taliban both internationally and nationally.

But economic sanctions also have a dire impact on the civilian population. Although the UN raised $1.2bn in emergency funds, the international community is grappling with how to engage with the Taliban, deliver the much-needed aid – and yet not empower, legitimise and enrich the Taliban. Helping Afghans while bypassing the Taliban is possible. Unicef, for example, is setting up a system that will allow direct payment to teachers while bypassing the Taliban.

Afghanistan’s state power monopoly owes more than $90 million to its power suppliers in neighbouring countries such as Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Given the deteriorating relationships between the Taliban and some of these countries, there are concerns that the suppliers might cut off electricity. International aid could be used to pay foreign electricity suppliers directly while denying the Taliban the opportunity to misappropriate funds.

Afghan civilians should not be subjected to starvation in a bid to pressure a government they did not put in office. Likewise, the international community has a responsibility to ensure the wealth of the Afghan people is not squandered by shortsighted Taliban desperately trying to cling to power.

Afghanistan is in a major humanitarian crisis: the health sector is failing, the economy is collapsing, and amid the COVID pandemic, famine is inflicting ever-larger numbers of casualties. According to the most recent report by the UN World Food Programme, more than half of the resident population of 38 million are facing acute hunger and 3.2 million children under five suffer from malnutrition.

Droughts, combined with the suspension of foreign aid in the aftermath of the Taliban’s takeover, have led to a dire economic situation, with recent reports indicating that some families in the northwest are selling their children out of desperation. Food and fuel prices are soaring.

On October 17, the Taliban foreign minister, Amir Khan Mottaqi, called on the US Congress to ease sanctions and release Afghanistan’s reserves. But would the US$9.5 billion (£7.16 billion) of frozen assets of Afghanistan Central Bank do anything to alleviate the deeply rooted poverty and food insecurity of the Afghan people – or will this only benefit the Taliban and its fighters?

Even in the near term, this amount of money will not go far to address poverty in Afghanistan. It has been estimated the reserves would cover the import costs of Afghanistan for only 15 months. The US-backed regime’s budget estimate for the fiscal year 2020 was $6.22 billion.

Join thousands of Canadians who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

The situation has been made worse by several other factors: drought, dependency on international aid and high unemployment rates. These extend far deeper and beyond the reach anything $9.5 billion could achieve. International aid made up about 75% of the US-backed regime’s budget. Afghanistan’s assets are only a fraction of the aid the country needs.

Skills deficit

It is naive to think that the Taliban’s caretaker cabinet and its civil service is able to administer these funds efficiently. The Taliban’s leadership lacks the knowledge, skill and experience needed to run state institutions and deliver services while managing an unfolding humanitarian crisis against the backdrop of a pandemic.

The COVID pandemic is playing havoc with Afghanistan’s economy. EPA-EFE/stringer

The skills that helped the Taliban win on the battlefield are not easily transferable. And more than half of the Taliban’s caretaker cabinet is on at least one designated terrorist list, which makes diplomatic engagement with the Taliban very difficult at the international level. At home, the Taliban leadership suffers from internal fragmentation that makes agreement on national-level public policy decisions difficult.

At the sub-national level, the Taliban has placed fighters in upper-level administration positions, while thousands of former government employees have either left their jobs or have been replaced with Taliban loyalists, according to my anonymous sources still living there. Women, who previously made up almost half of the civil service, have been almost entirely excluded. Taliban fighters placed at executive administrative levels lack the required managerial and leadership skills – some reportedly even lack basic literacy. The prospects of these people having the capacity to put the funds to productive use addressing the abject poverty in the country is very low.

Additionally, fears of misappropriation of National Bank’s assets are well-grounded. The limited international aid that has reached Afghanistan has occasionally been misappropriated and distributed among the Taliban fighters.

The skills that helped the Taliban win on the battlefield are not easily transferable. And more than half of the Taliban’s caretaker cabinet is on at least one designated terrorist list, which makes diplomatic engagement with the Taliban very difficult at the international level. At home, the Taliban leadership suffers from internal fragmentation that makes agreement on national-level public policy decisions difficult.

At the sub-national level, the Taliban has placed fighters in upper-level administration positions, while thousands of former government employees have either left their jobs or have been replaced with Taliban loyalists, according to my anonymous sources still living there. Women, who previously made up almost half of the civil service, have been almost entirely excluded. Taliban fighters placed at executive administrative levels lack the required managerial and leadership skills – some reportedly even lack basic literacy. The prospects of these people having the capacity to put the funds to productive use addressing the abject poverty in the country is very low.

Additionally, fears of misappropriation of National Bank’s assets are well-grounded. The limited international aid that has reached Afghanistan has occasionally been misappropriated and distributed among the Taliban fighters.

The Taliban is struggling to pay its fighters, let alone deal with growing food shortages.

EPA PHOTO POOL/AP

These concerns become all the more relevant given that the Taliban is not able to pay its fighters. The group has about 80,000 fighters who were paid 10,000-25,000 Afghanis (the equivalent of US$200-US$400) per month before the group took over Kabul. At the lower end, the Taliban needs at least $16m a month for the salaries of its fighters alone. Some of the Taliban’s fighters have reportedly defected to IS or al-Qaeda. The Taliban will undoubtedly lose more if it prioritises civilian spending over paying its fighters.

These concerns become all the more relevant given that the Taliban is not able to pay its fighters. The group has about 80,000 fighters who were paid 10,000-25,000 Afghanis (the equivalent of US$200-US$400) per month before the group took over Kabul. At the lower end, the Taliban needs at least $16m a month for the salaries of its fighters alone. Some of the Taliban’s fighters have reportedly defected to IS or al-Qaeda. The Taliban will undoubtedly lose more if it prioritises civilian spending over paying its fighters.

Political considerations

Finally, the release of Afghanistan’s foreign assets is tied to the question of the Taliban’s legitimacy. No government so far – including staunch supporter Pakistan – has officially recognised the Taliban’s government. Freezing Afghanistan’s assets was a political decision by US president Joe Biden to put pressure on the Taliban to form an inclusive government, so releasing these assets to the Taliban is akin to formal recognition of the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan. Even if it was released for entirely humanitarian reasons, the Taliban would not hesitate to make this into a propaganda coup.

Economic sanctions have been effective in some regards. The Taliban is realising that its survival depends on changing its policies, both regarding women’s rights and forming an inclusive government. The opening of schools for girls in cities such as Herat and Mazar-e Sharif is indicative of the effectiveness of pressure put on the Taliban both internationally and nationally.

But economic sanctions also have a dire impact on the civilian population. Although the UN raised $1.2bn in emergency funds, the international community is grappling with how to engage with the Taliban, deliver the much-needed aid – and yet not empower, legitimise and enrich the Taliban. Helping Afghans while bypassing the Taliban is possible. Unicef, for example, is setting up a system that will allow direct payment to teachers while bypassing the Taliban.

Afghanistan’s state power monopoly owes more than $90 million to its power suppliers in neighbouring countries such as Iran, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. Given the deteriorating relationships between the Taliban and some of these countries, there are concerns that the suppliers might cut off electricity. International aid could be used to pay foreign electricity suppliers directly while denying the Taliban the opportunity to misappropriate funds.

Afghan civilians should not be subjected to starvation in a bid to pressure a government they did not put in office. Likewise, the international community has a responsibility to ensure the wealth of the Afghan people is not squandered by shortsighted Taliban desperately trying to cling to power.

Author

Weeda Mehran

Lecturer in politics at the College of Social Sciences and International Studies, University of Exeter

Lecturer in politics at the College of Social Sciences and International Studies, University of Exeter

NEWS

December 15, 2021

The Taliban, United States military, and Afghan security forces were all responsible for attacks that resulted in extensive civilian suffering before the country’s government collapsed earlier this year, Amnesty International said in a new report today.

The report, No Escape: War Crimes and Civilian Harm During The Fall Of Afghanistan To The Taliban, documents torture, extrajudicial executions and killings by the Taliban during the final stages of the conflict in Afghanistan, as well as civilian casualties during a series of ground and air operations by the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) and US military forces.

Homes, hospitals, schools and shops were turned into crime scenes as people were repeatedly killed and injuredAgnès Callamard, Amnesty International Secretary General

“The months before the government collapse in Kabul were marked by repeated war crimes and relentless bloodshed committed by the Taliban, as well as deaths caused by Afghan and US forces,” said Agnès Callamard, Amnesty International’s Secretary General.

“Our new evidence shows that, far from the seamless transition of power that the Taliban claimed happened, the people of Afghanistan have once again paid with their lives.

“Homes, hospitals, schools and shops were turned into crime scenes as people were repeatedly killed and injured. The people of Afghanistan have suffered for too long, and victims must have access to justice and receive reparations.

“The International Criminal Court must reverse its misguided decision to deprioritize investigations into US and Afghan military operations, and instead follow the evidence on all possible war crimes, no matter where it leads.”

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan reported that 1,659 civilians were killed and another 3,524 injured in the first six months of 2021, an increase of 47% from the prior year.

Taliban atrocities

As they seized control of districts across Afghanistan in July and August 2021, members of the Taliban tortured and killed ethnic and religious minorities, former ANDSF soldiers, and those perceived as government sympathizers in reprisal attacks.

On 6 September 2021, Taliban forces attacked Bazarak town in Panjshir province. After a brief battle, approximately 20 men were captured by Taliban fighters and detained for two days, at times jailed in a pigeon coop. They were tortured, denied food, water and medical assistance, and repeatedly threatened with execution.

One of the men captured by the Taliban said: “[The] Talib had taken a knife… he was saying he wanted to behead the wounded… because they are infidels and Jews.”

Another man added: “They kept us underground. When we were asking for medical treatment of the wounded, the Taliban were saying, ‘Let them die’… There was no food and water, and no support to the wounded. They had brutal relations with us. When we were asking for water, they were saying, ‘Die of thirst’.” Torture and cruel and inhuman treatment of captives constitute war crimes.

Later the same day, the Taliban also attacked the nearby village of Urmaz, where they conducted door-to-door searches to identify people suspected of working for the former government. The fighters extrajudicially executed at least six civilian men within 24 hours, mainly by gunshots to the head, chest or heart. Such killings constitute war crimes. Eyewitnesses said that while some of the men had previously served in the ANSDF, none were in government security forces or taking part in hostilities in any way at the time of execution.

The report also documents reprisal attacks and executions of people affiliated with the former government in Spin Boldak. Amnesty International previously documented Taliban massacres of ethnic Hazaras in Ghazni and Daykundi provinces.

The full scale of the killings nationwide still remains unknown, as the Taliban cut mobile phone service, or severely restricted internet access, in many rural areas.

Civilian casualties from US and Afghan air strikes

The report documents four air strikes - three most likely carried out by US forces, and one by the Afghan Air Force - in recent years. The strikes killed a total of 28 civilians (15 men, five women, and eight children), and injured another six.

The strikes generally resulted in civilian deaths because the US dropped explosive weapons in densely populated areas. Amnesty International has previously documented similar impacts of explosive weapons in numerous other conflicts, and supports a political declaration to curb their use.

The second bomb killed my mother, my uncle, my aunt, and my sisterA nine-year-old child

On 9 November 2020, an air strike most likely carried out by US forces killed five civilians – including a three-month-old girl – and wounded six at a family home in the Mulla Ghulam neighbourhood of Khanabad city, in Kunduz province.

A nine-year-old child who was injured in the attack said: “I was sleeping when the first bomb hit… They were telling us to hide somewhere in case the second bomb happened. My father said I had to find my younger brother. The second bomb killed my mother, my uncle, my aunt, and my sister.”

Such strikes form a pattern of civilian harm that continued until the last moments of the conflict, when a US drone strike killed 10 people, including seven children, in Kabul on 29 August 2021. The US military later admitted that those killed were civilians.

Civilians killed in ground combat

The report documents eight cases during ground combat in which a total of 12 civilians were killed (five men, one woman, and six children), and 15 more injured. Through a combination of negligence and disregard for the law, the US-trained ANDSF frequently launched mortar attacks that hit homes and killed civilians in hiding.

The fighting in Kunduz city was especially fierce in June 2021. In the suburb of Zakhail, government forces launched mortars into densely populated neighbourhoods. Meanwhile, Taliban forces gained ground, using schools and mosques to launch attacks, and demanding food from families trapped in their homes.

On 22 June 2021, one man was killed and two people were injured during a mortar attack in Zakhail. The ANDSF most likely launched the mortar from the First Police District, approximately 2.5 kilometres from the scene of the explosion. The man killed was Abdul Razaq, 20, who was recently engaged to be married. Fragments from the mortar tore open his head and stomach.

Later the same day in the same neighbourhood, one child was killed and two more were injured when a mortar – again most likely launched by the ANDSF – hit a home where a family was in hiding. A metal fragment hit Manizha, a 12-year-old girl, in the spine, paralyzing and eventually killing her.

One man said the Taliban often forewarned families about combat, but they had received no similar communication from the government. He said: “The Taliban…say, ‘We will be fighting tonight’, and the people who can afford to leave do – but the poor people stay because they will starve if they leave. But there is no use of asking the government, when we know they are going to do nothing.”

The use of mortars, whose use in populated areas is inherently indiscriminate, can constitute a war crime.

Reparations and accountability

Multiple family members of victims of military actions told Amnesty International they did not receive sufficient, if any, reparations from the government.

One man, whose family home was destroyed in an air strike, said: “No one from the government came afterwards. We went to the district and told them what happened. No one came to us. They said, ‘This is not good. It should not have happened. We share your pain’. But nothing happened.”

The Taliban, United States military, and Afghan security forces were all responsible for attacks that resulted in extensive civilian suffering before the country’s government collapsed earlier this year, Amnesty International said in a new report today.

The report, No Escape: War Crimes and Civilian Harm During The Fall Of Afghanistan To The Taliban, documents torture, extrajudicial executions and killings by the Taliban during the final stages of the conflict in Afghanistan, as well as civilian casualties during a series of ground and air operations by the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) and US military forces.

Homes, hospitals, schools and shops were turned into crime scenes as people were repeatedly killed and injuredAgnès Callamard, Amnesty International Secretary General

“The months before the government collapse in Kabul were marked by repeated war crimes and relentless bloodshed committed by the Taliban, as well as deaths caused by Afghan and US forces,” said Agnès Callamard, Amnesty International’s Secretary General.

“Our new evidence shows that, far from the seamless transition of power that the Taliban claimed happened, the people of Afghanistan have once again paid with their lives.

“Homes, hospitals, schools and shops were turned into crime scenes as people were repeatedly killed and injured. The people of Afghanistan have suffered for too long, and victims must have access to justice and receive reparations.

“The International Criminal Court must reverse its misguided decision to deprioritize investigations into US and Afghan military operations, and instead follow the evidence on all possible war crimes, no matter where it leads.”

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan reported that 1,659 civilians were killed and another 3,524 injured in the first six months of 2021, an increase of 47% from the prior year.

Taliban atrocities

As they seized control of districts across Afghanistan in July and August 2021, members of the Taliban tortured and killed ethnic and religious minorities, former ANDSF soldiers, and those perceived as government sympathizers in reprisal attacks.

On 6 September 2021, Taliban forces attacked Bazarak town in Panjshir province. After a brief battle, approximately 20 men were captured by Taliban fighters and detained for two days, at times jailed in a pigeon coop. They were tortured, denied food, water and medical assistance, and repeatedly threatened with execution.

One of the men captured by the Taliban said: “[The] Talib had taken a knife… he was saying he wanted to behead the wounded… because they are infidels and Jews.”

Another man added: “They kept us underground. When we were asking for medical treatment of the wounded, the Taliban were saying, ‘Let them die’… There was no food and water, and no support to the wounded. They had brutal relations with us. When we were asking for water, they were saying, ‘Die of thirst’.” Torture and cruel and inhuman treatment of captives constitute war crimes.

Later the same day, the Taliban also attacked the nearby village of Urmaz, where they conducted door-to-door searches to identify people suspected of working for the former government. The fighters extrajudicially executed at least six civilian men within 24 hours, mainly by gunshots to the head, chest or heart. Such killings constitute war crimes. Eyewitnesses said that while some of the men had previously served in the ANSDF, none were in government security forces or taking part in hostilities in any way at the time of execution.

The report also documents reprisal attacks and executions of people affiliated with the former government in Spin Boldak. Amnesty International previously documented Taliban massacres of ethnic Hazaras in Ghazni and Daykundi provinces.

The full scale of the killings nationwide still remains unknown, as the Taliban cut mobile phone service, or severely restricted internet access, in many rural areas.

Civilian casualties from US and Afghan air strikes

The report documents four air strikes - three most likely carried out by US forces, and one by the Afghan Air Force - in recent years. The strikes killed a total of 28 civilians (15 men, five women, and eight children), and injured another six.

The strikes generally resulted in civilian deaths because the US dropped explosive weapons in densely populated areas. Amnesty International has previously documented similar impacts of explosive weapons in numerous other conflicts, and supports a political declaration to curb their use.

The second bomb killed my mother, my uncle, my aunt, and my sisterA nine-year-old child

On 9 November 2020, an air strike most likely carried out by US forces killed five civilians – including a three-month-old girl – and wounded six at a family home in the Mulla Ghulam neighbourhood of Khanabad city, in Kunduz province.

A nine-year-old child who was injured in the attack said: “I was sleeping when the first bomb hit… They were telling us to hide somewhere in case the second bomb happened. My father said I had to find my younger brother. The second bomb killed my mother, my uncle, my aunt, and my sister.”

Such strikes form a pattern of civilian harm that continued until the last moments of the conflict, when a US drone strike killed 10 people, including seven children, in Kabul on 29 August 2021. The US military later admitted that those killed were civilians.

Civilians killed in ground combat

The report documents eight cases during ground combat in which a total of 12 civilians were killed (five men, one woman, and six children), and 15 more injured. Through a combination of negligence and disregard for the law, the US-trained ANDSF frequently launched mortar attacks that hit homes and killed civilians in hiding.

The fighting in Kunduz city was especially fierce in June 2021. In the suburb of Zakhail, government forces launched mortars into densely populated neighbourhoods. Meanwhile, Taliban forces gained ground, using schools and mosques to launch attacks, and demanding food from families trapped in their homes.

On 22 June 2021, one man was killed and two people were injured during a mortar attack in Zakhail. The ANDSF most likely launched the mortar from the First Police District, approximately 2.5 kilometres from the scene of the explosion. The man killed was Abdul Razaq, 20, who was recently engaged to be married. Fragments from the mortar tore open his head and stomach.

Later the same day in the same neighbourhood, one child was killed and two more were injured when a mortar – again most likely launched by the ANDSF – hit a home where a family was in hiding. A metal fragment hit Manizha, a 12-year-old girl, in the spine, paralyzing and eventually killing her.

One man said the Taliban often forewarned families about combat, but they had received no similar communication from the government. He said: “The Taliban…say, ‘We will be fighting tonight’, and the people who can afford to leave do – but the poor people stay because they will starve if they leave. But there is no use of asking the government, when we know they are going to do nothing.”

The use of mortars, whose use in populated areas is inherently indiscriminate, can constitute a war crime.

Reparations and accountability

Multiple family members of victims of military actions told Amnesty International they did not receive sufficient, if any, reparations from the government.

One man, whose family home was destroyed in an air strike, said: “No one from the government came afterwards. We went to the district and told them what happened. No one came to us. They said, ‘This is not good. It should not have happened. We share your pain’. But nothing happened.”

The Taliban authorities now have the same legal obligation to provide reparations as the former governmentAgnès Callamard

Amnesty International is calling on the Taliban and the US government to fulfil their international obligations, and establish clear and robust mechanisms for civilians to request reparations for harm sustained during the conflict.

“The Taliban authorities now have the same legal obligation to provide reparations as the former government, and must address all issues of civilian harm seriously,” said Agnès Callamard.

“Victims and their families must receive reparations, and all those suspected of responsibility must be held to account in fair trials before ordinary civilian courts and without recourse to the death penalty.”

Methodology

Amnesty International conducted on-the-ground research in Kabul from 1-15 August 2021, and completed remote phone interviews with victims and witnesses via secure video and voice calls from August to November 2021.

Amnesty International conducted face-to-face interviews in Kabul with 65 people, and remote interviews through encrypted mobile apps with an additional 36 people, from a total of 10 provinces.

The organization’s Crisis Evidence Lab also reviewed satellite imagery, videos and photographs, medical and ballistics information, and interviewed relevant experts where necessary.

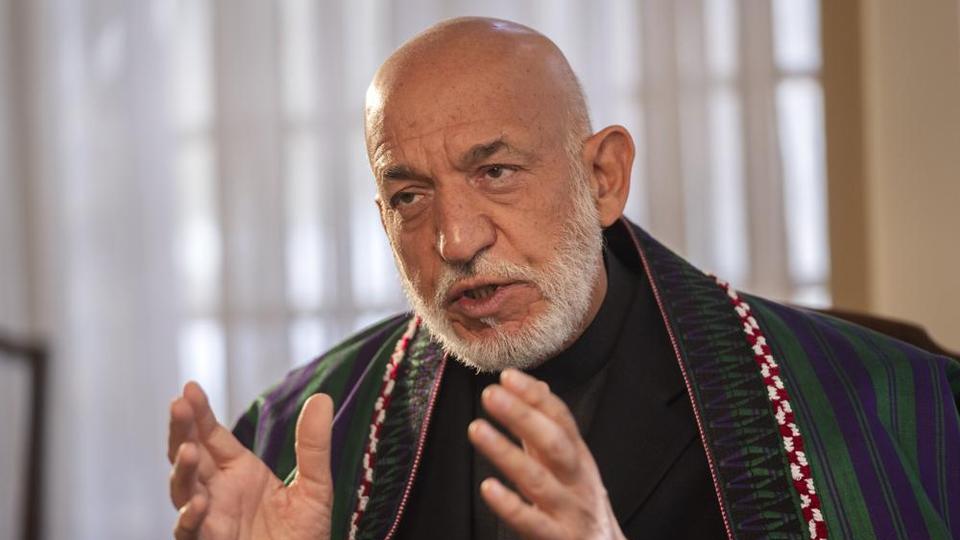

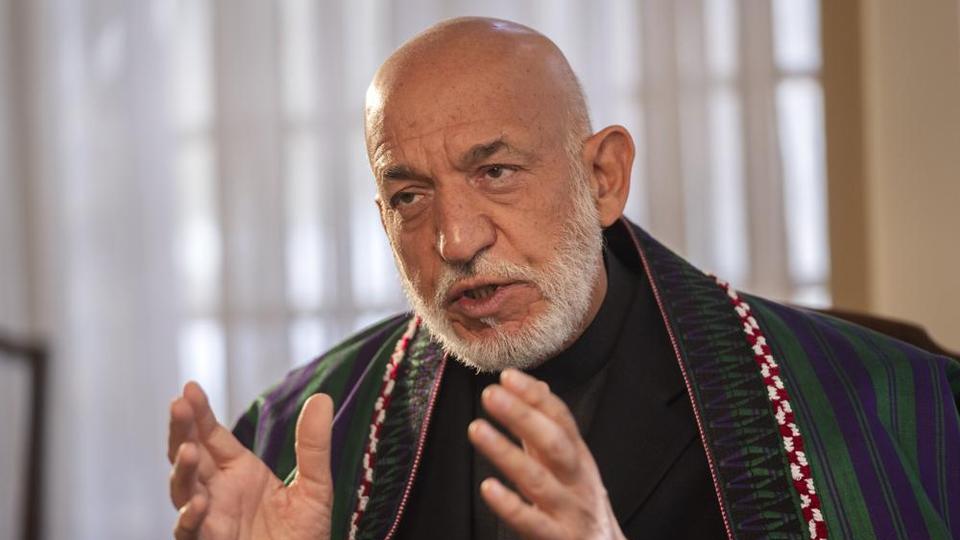

Karzai 'invited' Afghan Taliban to Kabul after Ghani fled in secret

Ex-Afghan leader Hamid Karzai says he invited the Taliban insurgents into the capital Kabul on August 15 so that "the city doesn't fall into chaos," following a covert departure of Ashraf Ghani and his team from the country.

Ghani scuttled peaceful transition

Karzai said that Ghani's flight scuttled a last-minute push by himself, the government's chief negotiator Abdullah Abdullah and the Taliban leadership in Doha that would have seen the Taliban enter the capital as part of a negotiated agreement.

The countdown to a possible deal began on August 14, the day before the Taliban came to power.

Karzai and Abdullah met Ghani, and they agreed that they would leave for Doha the next day with a list of 15 others to negotiate a power-sharing agreement.

The Taliban were already on the outskirts of Kabul, but Karzai said the leadership in Qatar promised the Taliban will remain outside the city until the deal was struck.

Early on the morning of August 15, Karzai said, he waited to draw up the list. The capital was fidgety, on edge. Rumors were swirling about a Taliban takeover. Karzai called Doha. He was told the Taliban would not enter the city.

At noon, the Taliban called to say that "the government should stay in its positions and should not move that they have no intention to (go) into the city," Karzai said.

"I and others spoke to various officials and assurances were given to us that, yes, that was the case, that the Americans and the government forces were holding firm to the places (and) that Kabul would not fall."

By about 2:45 pm, though, it became apparent Ghani had fled the city. Karzai said he called the defence minister, called the interior minister, searched for the Kabul police chief but everyone was gone.

"There was no official present at all in the capital, no police chief, no corps commander, no other units. They had all left."

READ MORE: 'God will punish them': Afghan victims reject US verdict on Kabul killings

Engagement with Taliban

Karzai said he meets regularly with the Taliban leadership and said the world must engage with them.

"Right now, they need to cooperate with the government in any form they can," said Karzai, who also bemoaned the unchallenged and sometimes wrong international perceptions of the Taliban.

He cited claims that women and girls are not allowed outside their homes or require a male companion.

"That's not true. There are girls on the streets — women by themselves. The situation on the ground in Kabul bears this out."

READ MORE: Caught in cyclical violence: Why Afghanistan's present mirrors its past

Ex-Afghan leader Hamid Karzai says he invited the Taliban insurgents into the capital Kabul on August 15 so that "the city doesn't fall into chaos," following a covert departure of Ashraf Ghani and his team from the country.

Karzai says Ghani's flight scuttled a last-minute push that would have seen the Taliban enter the capital as part of a negotiated deal. (AP)

Former Afghanistan president Hamid Karzai has said the Taliban didn't take the Kabul city on August 15 but they were invited by him to enter the Afghan capital after former president Ashraf Ghani and his team fled the country, creating a security vacuum.

In an Associated Press interview on Wednesday, Karzai offered some of the first insights into the secret and sudden departure of Ghani — and how he came to invite the Taliban into the city "to protect the population so that the country, the city doesn't fall into chaos and the unwanted elements who would probably loot the country, loot shops."

Karzai said when Ghani fled, his security officials also left, adding defence minister Bismillah Khan even asked him if he wanted to leave Kabul when he contacted him to know what remnants of the government still remained.

It turned out there were none, not even the Kabul police chief had remained, Karzai said.

Karzai, who was the country's president for 13 years after the Taliban was first ousted in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, said he refused to leave.

READ MORE:

Former Afghanistan president Hamid Karzai has said the Taliban didn't take the Kabul city on August 15 but they were invited by him to enter the Afghan capital after former president Ashraf Ghani and his team fled the country, creating a security vacuum.

In an Associated Press interview on Wednesday, Karzai offered some of the first insights into the secret and sudden departure of Ghani — and how he came to invite the Taliban into the city "to protect the population so that the country, the city doesn't fall into chaos and the unwanted elements who would probably loot the country, loot shops."

Karzai said when Ghani fled, his security officials also left, adding defence minister Bismillah Khan even asked him if he wanted to leave Kabul when he contacted him to know what remnants of the government still remained.

It turned out there were none, not even the Kabul police chief had remained, Karzai said.

Karzai, who was the country's president for 13 years after the Taliban was first ousted in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, said he refused to leave.

READ MORE:

Ghani scuttled peaceful transition

Karzai said that Ghani's flight scuttled a last-minute push by himself, the government's chief negotiator Abdullah Abdullah and the Taliban leadership in Doha that would have seen the Taliban enter the capital as part of a negotiated agreement.

The countdown to a possible deal began on August 14, the day before the Taliban came to power.

Karzai and Abdullah met Ghani, and they agreed that they would leave for Doha the next day with a list of 15 others to negotiate a power-sharing agreement.

The Taliban were already on the outskirts of Kabul, but Karzai said the leadership in Qatar promised the Taliban will remain outside the city until the deal was struck.

Early on the morning of August 15, Karzai said, he waited to draw up the list. The capital was fidgety, on edge. Rumors were swirling about a Taliban takeover. Karzai called Doha. He was told the Taliban would not enter the city.

At noon, the Taliban called to say that "the government should stay in its positions and should not move that they have no intention to (go) into the city," Karzai said.

"I and others spoke to various officials and assurances were given to us that, yes, that was the case, that the Americans and the government forces were holding firm to the places (and) that Kabul would not fall."

By about 2:45 pm, though, it became apparent Ghani had fled the city. Karzai said he called the defence minister, called the interior minister, searched for the Kabul police chief but everyone was gone.

"There was no official present at all in the capital, no police chief, no corps commander, no other units. They had all left."

READ MORE: 'God will punish them': Afghan victims reject US verdict on Kabul killings

Engagement with Taliban

Karzai said he meets regularly with the Taliban leadership and said the world must engage with them.

"Right now, they need to cooperate with the government in any form they can," said Karzai, who also bemoaned the unchallenged and sometimes wrong international perceptions of the Taliban.

He cited claims that women and girls are not allowed outside their homes or require a male companion.

"That's not true. There are girls on the streets — women by themselves. The situation on the ground in Kabul bears this out."

READ MORE: Caught in cyclical violence: Why Afghanistan's present mirrors its past

No comments:

Post a Comment