Migrant workers have endured exploitative, even deadly, conditions as Qatar prepared for the World Cup. The ‘beautiful game’ has blood on its hands

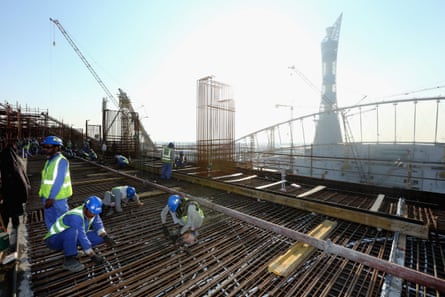

Construction workers at Lusail Stadium during a media tour in Doha,

Qatar, 20 December 2019. Photograph: Ali Haider/EPA

Guardian

Tue 15 Nov 2022

On a corner of my desk stands a giant stack of external hard drives. They hold the story, gigabyte after gigabyte, of almost a decade of reporting on the lives of Nepal’s migrant workers in the World Cup host nation, Qatar.

On one, I recently found a photo from July 2013 of Tilak Bishwakarma holding a picture of his son Ganesh. When he left his home for Qatar, Ganesh was a teenager hoping to earn some money to support his impoverished family. Two months later his body was brought home in a coffin.

I opened another photo, showing a tattered piece of paper, listing the names of 22 other Nepali workers who died in Qatar that July. Beside each name is written the cause of death: electrocution, falls, road traffic accident. On 17 July came Ganesh’s name. Cause of death: cardiac arrest.

Ganesh’s short life formed part of a major investigation into the treatment of Qatar’s vast low-wage migrant workforce (almost 90% of the country’s population comprises migrant workers). It revealed an appalling catalogue of abuses – overcrowded, filthy accommodation, passport confiscation and non-payment of wages – which in some cases may have amounted to forced labour, a modern form of slavery.

When the Guardian published its exclusive story in September 2013 after I saw the coffins of Nepali workers returning home from the Gulf, it made headlines around the world. Football was literally coming down to a matter of life and death. There was something deeply offensive about the exploitation of some of the world’s poorest people in the name of a festival of sport.

Fifa immediately said it was “very concerned”, though clearly not concerned enough to have done its own due diligence. The next day Qatar’s World Cup organisers sent a letter to the game’s governing body assuring it that they viewed the Guardian’s findings with the “utmost seriousness”. Attached to the letter was a one-page “Workers’ Charter” setting out, in skeletal form, their commitment to workers’ rights.

On one, I recently found a photo from July 2013 of Tilak Bishwakarma holding a picture of his son Ganesh. When he left his home for Qatar, Ganesh was a teenager hoping to earn some money to support his impoverished family. Two months later his body was brought home in a coffin.

I opened another photo, showing a tattered piece of paper, listing the names of 22 other Nepali workers who died in Qatar that July. Beside each name is written the cause of death: electrocution, falls, road traffic accident. On 17 July came Ganesh’s name. Cause of death: cardiac arrest.

Ganesh’s short life formed part of a major investigation into the treatment of Qatar’s vast low-wage migrant workforce (almost 90% of the country’s population comprises migrant workers). It revealed an appalling catalogue of abuses – overcrowded, filthy accommodation, passport confiscation and non-payment of wages – which in some cases may have amounted to forced labour, a modern form of slavery.

When the Guardian published its exclusive story in September 2013 after I saw the coffins of Nepali workers returning home from the Gulf, it made headlines around the world. Football was literally coming down to a matter of life and death. There was something deeply offensive about the exploitation of some of the world’s poorest people in the name of a festival of sport.

Fifa immediately said it was “very concerned”, though clearly not concerned enough to have done its own due diligence. The next day Qatar’s World Cup organisers sent a letter to the game’s governing body assuring it that they viewed the Guardian’s findings with the “utmost seriousness”. Attached to the letter was a one-page “Workers’ Charter” setting out, in skeletal form, their commitment to workers’ rights.

A demonstrator holds a placard critical of Qatar’s policies regarding the working conditions of migrant workers before a friendly between Scotland and Qatar in Edinburgh. Photograph: Andy Buchanan/AFP/Getty Images

For the next nine years, that commitment would be relentlessly tested and challenged by the Guardian’s reporting. (If you value our dogged pursuit of justice, safety and fairness, please consider supporting our journalism today.)

We exposed how workers from North Korea were building a tower block – now a luxury hotel booked up by football fans – under conditions likely to constitute slave labour.

We documented the poverty wages being paid to the men constructing the new stadiums. In 2014 one told us he was earning overtime pay the equivalent of 45 pence an hour. Four years later another said his basic wage worked out at 60 pence an hour – 10,000 times less than the reported earnings of Lionel Messi.

We revealed that thousands of south Asian workers had died in Qatar in the decade after it won the right to host the World Cup, many from sudden and unexplained causes. The Qatari authorities have done little to investigate these deaths and countless families of the deceased have not received compensation from their employers.

For the next nine years, that commitment would be relentlessly tested and challenged by the Guardian’s reporting. (If you value our dogged pursuit of justice, safety and fairness, please consider supporting our journalism today.)

We exposed how workers from North Korea were building a tower block – now a luxury hotel booked up by football fans – under conditions likely to constitute slave labour.

We documented the poverty wages being paid to the men constructing the new stadiums. In 2014 one told us he was earning overtime pay the equivalent of 45 pence an hour. Four years later another said his basic wage worked out at 60 pence an hour – 10,000 times less than the reported earnings of Lionel Messi.

We revealed that thousands of south Asian workers had died in Qatar in the decade after it won the right to host the World Cup, many from sudden and unexplained causes. The Qatari authorities have done little to investigate these deaths and countless families of the deceased have not received compensation from their employers.

Construction workers on Doha’s Khalifa International Stadium in 2015.

Photograph: Warren Little/Getty Images

Last year we found workers employed at opulent Fifa-endorsed hotels trapped by recruitment debts and rogue employers, earning less in a month than the cost of a standard room for a night.

Advertisement

And in September we revealed that some labourers at World Cup stadiums were living in squalid, windowless cabins on the edge of the desert.

Low-wage migrant workers face a cruel choice: stay at home and suffer, or take the risk and go abroad. For some the gamble pays off – money is sent home, houses are rebuilt and children sent to school – but for too many it’s a bet they lose.

Reporting from Qatar is not easy, but the only way to really tell this story is to be on the ground, feel the searing heat, see the overcrowded labour camps and listen. And that’s the hardest part. People are afraid to speak, because however tough their circumstances are, they need the work, so why put that at risk to talk to a journalist?

Before each trip I agree protocols with my editor in the event that I’m detained (as a number of journalists have been). Once in Qatar, I am constantly looking over my shoulder, metaphorically and literally. Interviews take place at night, or parked up on a quiet street or in the back of a nondescript restaurant. But by working independently and undercover we have been able to expose what they hoped to keep hidden.

Last year we found workers employed at opulent Fifa-endorsed hotels trapped by recruitment debts and rogue employers, earning less in a month than the cost of a standard room for a night.

Advertisement

And in September we revealed that some labourers at World Cup stadiums were living in squalid, windowless cabins on the edge of the desert.

Low-wage migrant workers face a cruel choice: stay at home and suffer, or take the risk and go abroad. For some the gamble pays off – money is sent home, houses are rebuilt and children sent to school – but for too many it’s a bet they lose.

Reporting from Qatar is not easy, but the only way to really tell this story is to be on the ground, feel the searing heat, see the overcrowded labour camps and listen. And that’s the hardest part. People are afraid to speak, because however tough their circumstances are, they need the work, so why put that at risk to talk to a journalist?

Before each trip I agree protocols with my editor in the event that I’m detained (as a number of journalists have been). Once in Qatar, I am constantly looking over my shoulder, metaphorically and literally. Interviews take place at night, or parked up on a quiet street or in the back of a nondescript restaurant. But by working independently and undercover we have been able to expose what they hoped to keep hidden.

A room at the camp which houses workers employed at a number

of World Cup stadiums in Qatar.

Photograph: Pete Pattisson/The Guardian

So as the World Cup kicks off, if you value reading about the action in the stadiums, but also about the people who built them, please consider supporting a news organisation determined to expose the truth behind the slick PR of Big Football and the Gulf petrocrats. You can fund our work today, from just £1. If you can, please consider giving a little more each month or year.

It makes a difference. The cumulative pressure of our reporting, alongside the work of human rights groups and trade unions, forced the Qatari authorities to belatedly introduce a number of new laws that have the potential to create real change for low-wage workers.

The abusive kafala system, under which workers cannot change jobs without their employer’s permission, has – on paper – been abolished and a minimum wage has been introduced.

The reforms have neither gone far enough nor been implemented rigorously. But that’s why this work matters. When the Qatari authorities and Fifa make overblown claims about what they have achieved, we will challenge them.

Our reporters know that it’s about so much more than what happens on the pitch.

Support vital, investigative Guardian journalism today.

So as the World Cup kicks off, if you value reading about the action in the stadiums, but also about the people who built them, please consider supporting a news organisation determined to expose the truth behind the slick PR of Big Football and the Gulf petrocrats. You can fund our work today, from just £1. If you can, please consider giving a little more each month or year.

It makes a difference. The cumulative pressure of our reporting, alongside the work of human rights groups and trade unions, forced the Qatari authorities to belatedly introduce a number of new laws that have the potential to create real change for low-wage workers.

The abusive kafala system, under which workers cannot change jobs without their employer’s permission, has – on paper – been abolished and a minimum wage has been introduced.

The reforms have neither gone far enough nor been implemented rigorously. But that’s why this work matters. When the Qatari authorities and Fifa make overblown claims about what they have achieved, we will challenge them.

Our reporters know that it’s about so much more than what happens on the pitch.

Support vital, investigative Guardian journalism today.

No comments:

Post a Comment