An Opportune Time For System Change?

By Ann Pettifor

May 13, 2024

Source: System Change

Images Money - Dollar. Flickr.

As I write, the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) is preparing a ground offensive on Rafah, Palestine . PM Netanyahu has warned for months that such an offensive was imminent. The consensus view was that US pressure was all that held the IDF back from another slaughter of innocents; a battle that would not lead to the release of hostages, and would ultimately strengthen Hamas.

Then a US-sponsored deal – overseen by CIA director William J. Burns – accepted by Hamas, was rejected by Israel.

The consensus view was wrong. Israel, against the apparent advice of the United States president, proceeded defiantly with an attack bound to kill and maim many thousands more innocent civilians, including children and hostages – and to threaten the security of the wider region.

So far, so fairly predictable. Except this – from a professor of American history:

Over the last 130 years there was, and is no situation anywhere in the world where the mighty US of A has not used its leverage “to shape the behaviour of others.”

Israel is ranked way down the global economy in terms of size, population and GDP, and is dependent on the US for military aid. “Shaping its behaviour” should, theoretically, be easier. The country has a population of just 10 million people (not much bigger than the population of London); spends $26bn on the military and has an economy of just half a trillion dollars ($525bn) – according to the World Bank. Contrast that with the US with an annual GDP of $25 trillion and with the world’s highest military expenditure of $916 billion; and a population of 330 million. And to crown its power the US is issuer of the world’s reserve currency: the US dollar.

Yet the Israeli state has succeeded in subordinating the mighty United States of America to its murderous will.

The result is that at a time when the war on Palestine poses a grave threat not only to Palestinians in Gaza and on the West Bank; not only to the security of the Israeli people, but also to the region as a whole

the US has no plans to use its vast leverage ..to deliver even an ounce of peace and justice.

America’s Waning Power – Is It Real?

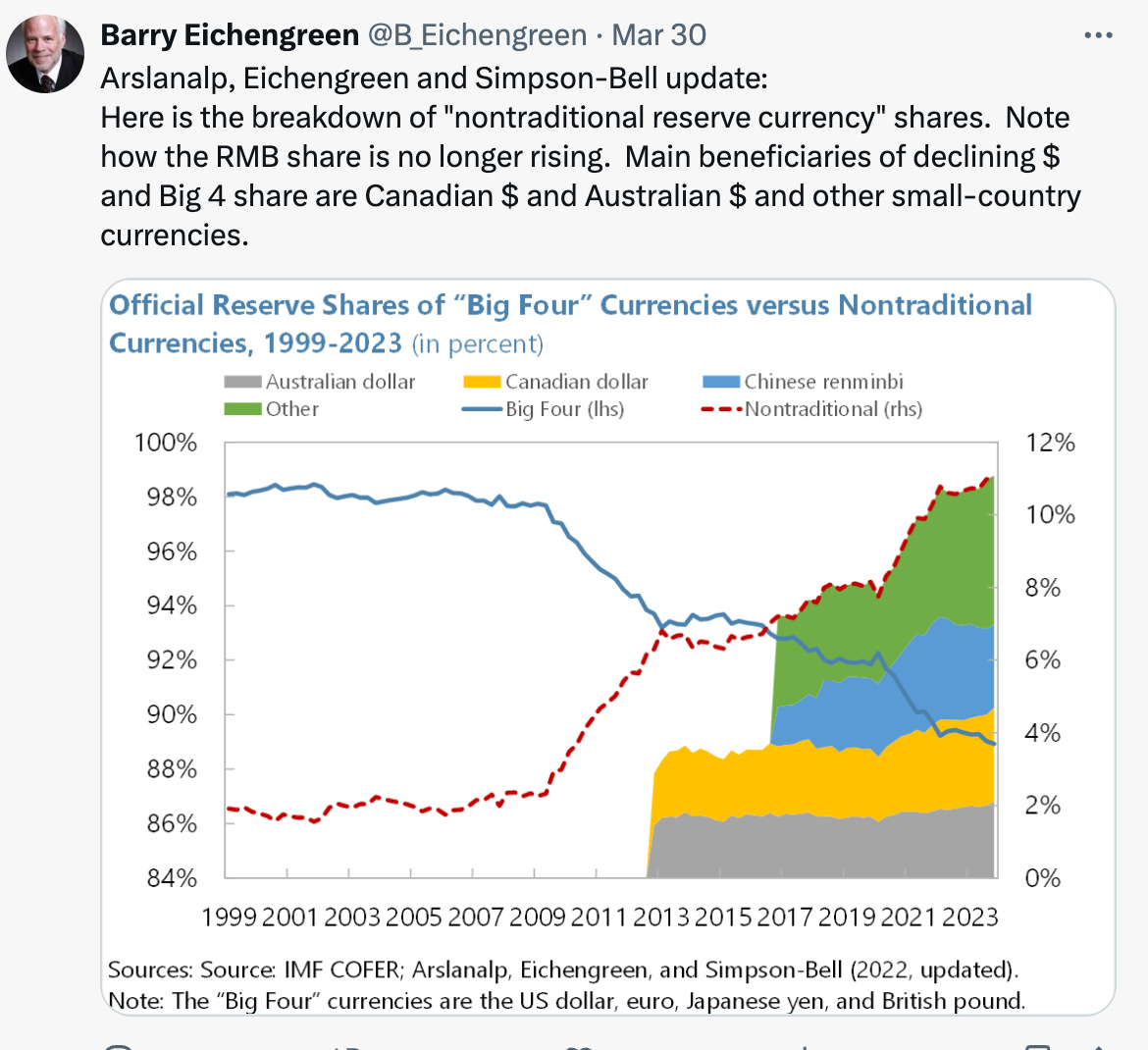

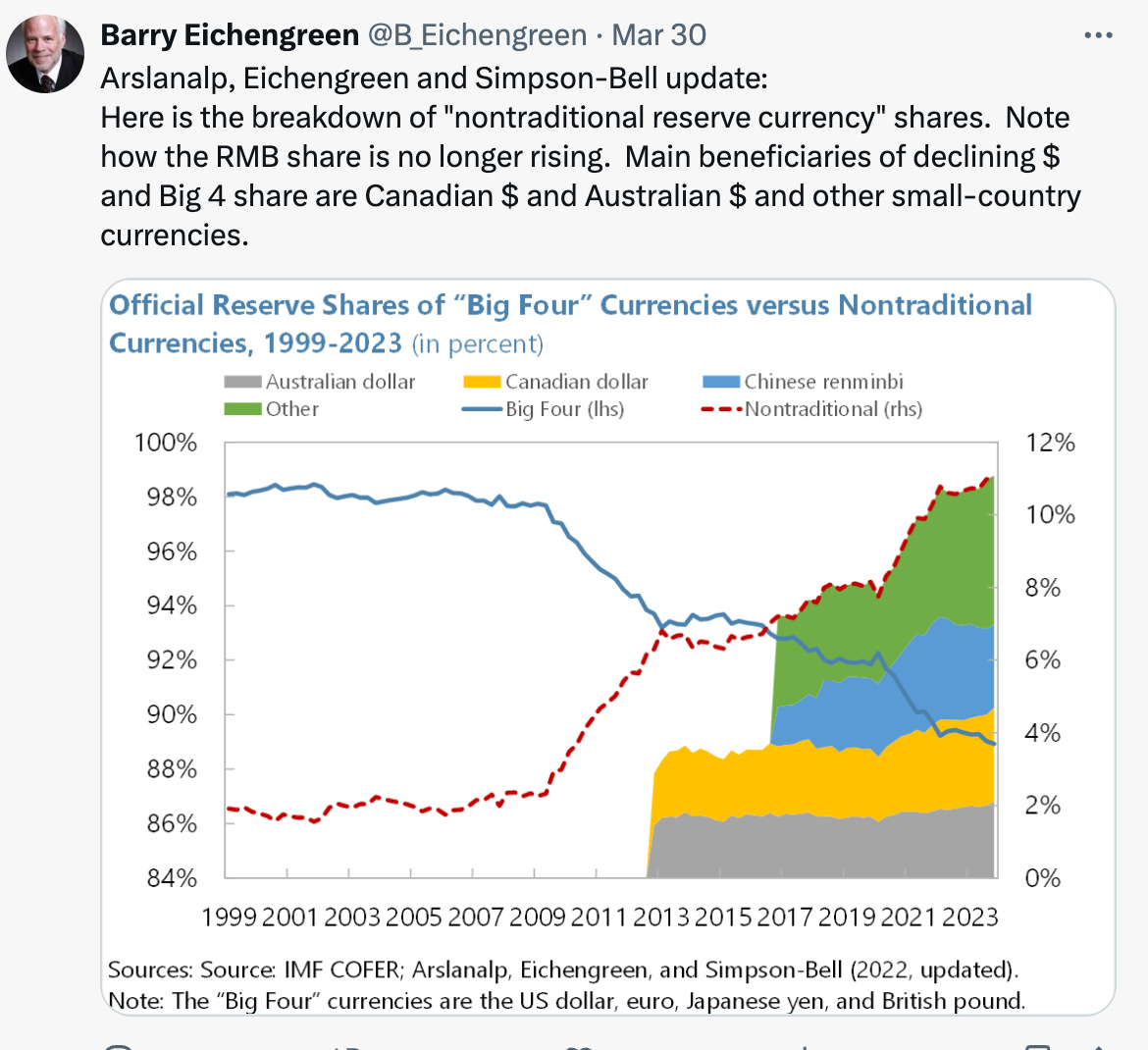

Given these developments, the United States appears weak, even impotent. This has excited talk of American imperial decline, and of the inevitable demise of the world’s reserve currency, the US dollar.

I am frankly, sceptical of such speculation. The US economy and its currency are mighty powerful – and not easily displaced.

Nevertheless it is important to pay attention to these matters, because we are all affected – albeit differentially – by the power of the US economy, and by the strength or weakness of the US dollar and its use in currency and commodity trading.

Poor countries suffer the most. They are victims (and beneficiaries) of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy (interest rates and Quantitative Easing (QE)) and on the strengthening or weakening of the US dollar; a currency in which they are obliged to borrow, and to buy and sell essential commodities (like food, medicines and energy).

Many low and middle-income countries are debating whether the US dollar, and therefore US power over the global economy, can be displaced? And if so, would that mean turning to, and relying on another reserve currency, like the Chinese yuan, or the Russian ruble?

That debate will soon hit the brick wall of realpolitik. Choosing an alternative national currency as the world’s reserve currency would simply mean choosing an alternative hegemon to that of the United States.

Instead of an alternative currency; or even multiple currencies, countries should argue for a change to the international system – and an end to dependence on a single hegemonic currency – and to the chaotic trading arrangements that hurt all countries – including the United States.

Instead countries of the majorityworld should argue for the establishment of a far more neutral and independent International Clearing Union – as a way of settling international payments – along the lines proposed by John Maynard Keynes in 1944.

Because there is so little knowledge or understanding of Keynes’s proposal for a clearing union, what follows will briefly outline the current context of the de-dollarisation debate, and then the principles of Keynes’s Clearing Union and the implications for BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, China, India and South Africa).

This will be followed, a day later, with a post on the special, but urgent case: the need for an African Payments Union.

A gentle warning: its fascinating, but a little bit nerdy.

The context: the market-driven global economy in 2024

Today’s economy can be characterised as one almighty, and badly entangled mess.

Comparable perhaps to the mess that is the world’s dirty, carbonised atmosphere.

This mess is due to a) the absence of effective state management of the international financial (and eco) system; b) the mobility and volatility of speculative capital; c) leading to obscene levels of inequality – both within and between countries; and d) by trade and capital account imbalances – a consequence of financial and trade deregulation, over-production and under consumption – all leading to trade wars.

Since early in the 1960s when Wall St financiers began to dismantle the Bretton Woods architecture in earnest, management of trade, currency, commodity and money markets was gradually wrenched away from states.

That transfer from public (democratic) authority to private authority over the world economy, has immense implications for states wishing to tackle e.g. inequality; unemployment; public services, but also climate and ecosystem breakdown.

The de-dollarisation debate

This is the chaotic market-driven context in which a range of alternatives to dollar dominance are currently debated by countries of the global majority.

The angry de-dollarisation debate is prompted in part by the freezing of half of Russia’s central bank gold and foreign exchange reserves first by Europe, and then the United states in March 2022. It was coupled with the decision to disconnect Russian banks from the Belgium-based Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

Two years later at a special sitting on Saturday, 20 April, 2024, the US Congress passed a foreign aid package that would permit the Biden administration to confiscate $6 billion of Russian assets in US banks and transfer the proceeds to Ukraine.

The law contains policy provisions under which (i) the statute of limitations for US sanctions violations would be doubled; (ii) frozen Russian state-owned assets could be seized and used to support Ukraine, (iii) additional sanctions would be imposed on Russia, Iran, and Hamas; and (iv) data brokers would be prohibited from transferring personally identifiable sensitive data of US individuals to foreign adversaries.

The confiscation of state assets is an extraordinary development for a capitalist economy that regards property rights as almost sacred; and that promotes a ‘rules-based international order.’

The majority world’s angry response

Angry Chinese, African and Latin American leaders responded quickly. If the United States can seize Russia’s assets held in their trust at e.g. the Federal Reserve or the ECB, they asked, what stops the US from seizing the assets of any other state they disapproved of?

As Robert Greene of the Carnegie Endowment Fund reports, South Africa’s President Ramaphosa expressed concern that

global financial and payment systems are increasingly being used as instruments of geopolitical contestation.

At the April 2023 BRICS summit, where Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were invited to join the bloc, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva asked (to thunderous applause):

“Why can’t we do trade based on our own currencies? Who was it that decided that the dollar was the currency after the disappearance of the gold standard?”

BRICS finance ministers and central bankers were tasked by the 2023 BRICs summit to report back the following year on the question of local currencies’ use and payments infrastructure, according to Reuters. Later, in November 2023, a Leading Chinese Communist Party (CCP) political journal stated that recent U.S. monetary policy choices created a “dollar tide” that

seizes the wealth of other countries and forces developing countries to bear the huge economic losses and financial risks brought about by the hegemony of the dollar.

As a result of these concerns China’s renminbi is increasingly used for cross-border payments – even while such payments are limited relative to the U.S. dollar. It’s use in China’s cross-border transactions grew from around 20 per cent to approximately 50 percent between 2016 and 2022, according to Bloomberg. Russia’s finance minister explained to the TASS news agency on 19 September, 2023 that 70 percent of China-Russia trade was settled in renminbi during the first three quarters of 2023. In May 2023, Russian authorities were reportedly considering using the renminbi to facilitate trade with Iran. In the meantime, it is reported that the Russian central bank is encouraging countries in the use of its alternative to SWIFT for transmitting financial messages: SPFS.

The alternative: An International Clearing Union: what is it?

An International Clearing Union (ICU) would end dependence on any one currency; and would manage the payments part of the world’s trading system.

Here’s how to think about it.

A Clearing Union system is comparable to the domestic, commercial banking system which, with the help of the central bank, manages payments between buyers and sellers undertaking business transactions and borrowing or paying for those via a bank. The difference is that the buyers and sellers in the ICU would be nations, channelling the cross-border transactions of their citizens – individuals and corporations.

To understand the management of a clearing union, think of the central bank’s role within a commercial banking system. As we borrow, deposit, or withdraw money from banks, bankers are required to ‘balance their books’. on a daily basis. (Managing stocks and flows of money in and out of banks, is hard, and often not profitable.)

Central bank reserves can’t be used outside of the banking system. The central bank dispenses or absorbs these reserves to keep the whole commercial, licensed banking system stable as it manages thousands of transactions every day.

Of course its much more complicated than that – time and interest rates play a big part – but you get the big picture.

In just the same way an international institution – say the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, the Big Daddy of central banks) – based in Basel, Switzerland, could play the role of ‘central banker’ or supervising authority to nations trading with each other. Trade will be undertaken in their own currencies and the foreign exchange arrangements settled by the supervising authority, if it is the BIS.The authority’s actions would be transparent; and would keep tabs on surpluses and deficits within the trading system. It would do so in the neutral way a central bank treats the commercial banks within its domain. Keynes envisioned that such a neutral institution would have an apolitical structure – which is what central banks are supposed to have. Unlike the IMF – which has a highly politicised board of management – central banks do not discriminate against debtor banks within its system; or force only debtor banks to restore balance and make the necessary adjustment. It treats both debtor and creditor banks the same. After all, imbalances are inevitable, and central to the very nature of the banking business. Nor do central banks consciously set economic terms and conditions that would harm the economic stability of the banks within its care, as the IMF does.

Jane D’Arista – an expert on the ICU, expanded on these points in a book I edited in 2003: The Real World Economic Outlook. She explained that

…..an importer in country A would pay for machinery from country B by writing a check on his bank account in his own currency. The seller in country B would deposit the check in his bank and receive credit in his own currency at the current rate of exchange between the two currencies. This would be possible because of the existence of an international clearing process that would route the check from the commercial bank to the central bank in country B and from there to the international clearing agency (ICA).

At the end of the day, the ICA would net all checks exchanged between two countries and pay the difference by debiting or crediting their reserve accounts.

The process is simple but it does imply certain rules. It would require that all commercial banks receiving foreign payments exchange them for domestic currency deposits with their central banks. The central banks, in turn, would be required to deposit all foreign payments with the ICA. The result would be that all international reserves would be held by the ICA and that the process of debiting and crediting payments against countries’ reserve accounts would provide the means for determining changes in exchange rates. As in national systems where the level of required reserves is determined at weekly or bi-weekly intervals, such a structure would greatly reduce the exchange rate volatility that currently plagues the system.

An ICUwould not need a common currency to function, or if it did, that currency would only be used within and between members of the clearing union itself.

The importance of balancing the international trading system

By keeping accounts of payments in and out of the ICU and clearing transactions between trading nations, the ICU could help ensure member nations don’t build up deficits (overdrafts) but also surpluses – and that they always pay their dues.

Both trading debtors and creditors would be penalised – with higher rates of interest on outstanding payments, or on surpluses. That is because, in macroeconomic terms, one country’s trade surplus is another’s trade deficit. It may seem counter-intuitive, but trade surpluses are as harmful to international trade stability as deficits.

The policies that help build up trade surpluses are known as ‘beggar thy neighbour’ policies – where one country solves its domestic economic problems by dumping (sic) on another. And so, within a clearing union, both debtor (deficit) and creditor (surplus) countries would have to adjust, to restore balance to the world’s trading system. Trade surplus countries (like China, Kuwait or Germany) would do this by buying more from trade deficit countries (like the US, the United Kingdom or South Africa) to help restore stability to the international system as a whole.

Today the international trading system is neither supervised nor managed. Instead there are vast imbalances between surplus and deficit countries, and these in turn are the result of a) imbalances in the domestic economy and b) a cause of trade wars. (That is why Klein and Pettis’s book title: Trade Wars are Class Wars – is so pertinent.)

Surely such ‘system change’ is pie-in-the-sky?

Now many have argued that to replace the US dollar’s reserve status with an international clearing union would be nigh impossible. But we disagree. The ‘we’ referred to here includes two brilliant Italian economists, Massimo Amato and Luca Fantacci and myself. Back in 2019 we wrote in Open Democracy about an important precedent: an inter-national clearing union that had worked most successfully in recent history: the European Payments Union (EPU) of the 1950s. Amato and Fantacci explain how – in contrast to the Marshall Plan – the EPA had been successful in restoring economic health to a devastated, post-war Europe.

The European Payments Union (EPU) was established between 1950 and 1958.

The EPU made it possible for each country to finance its current account deficits without relying on the vagaries of capital liquidity provided by international financial markets, by providing a ‘clearing centre’. The country’s position was recorded as a net position in relation to the clearing centre itself, and thus as a multilateral position in relation to all the other countries.

A quota was set for each country corresponding to 15% of its trade with the other countries in the Union. Credit and debit balances could not exceed the respective quotas. The system therefore set a limit on the accumulation of debts or deficits with the clearing centre, and provided debtors with an incentive to converge towards equilibrium with their trading partners. The EPU also exerted strong pressure on creditor countries which, like Germany and Holland today, failed to raise imports and cut their surpluses.

The result was an extraordinary, export-driven expansion in production, in Germany and Italy in particular, and the liberalisation of trade not only within the EU, but also well beyond.

But what was most extraordinary was that this expansion of trade came along with rising employment and welfare in each partner country: the EPU was a part of a superstructure that provided countries with more autonomy to foster an economy led by domestic demand.

In other words: the Marshall Plan merely provided liquidity – i.e. cash – which at a time of European economic devastation was largely used by Europeans to buy American goods. That suited Americans very well, and allowed the country to maintain high levels of wartime production. However, it did not help Europe recover production, employment and income at home. The EPA by contrast, provided European countries with the kind of ‘overdrafts’ that permitted them to begin investing, producing and trading their own goods and services – which in turn generated employment and income – at home.

Unfortunately the system was dismantled by the ideology of ‘free markets’ and untrammelled capital flows…the very system that has bestowed today’s chaotic, divisive and unbalanced global economy on us all.

Which way forward?

Given all of the above, how could interim changes to the monetary system, along the lines proposed by Keynes, be made to ease global trade tensions? And how could such changes strengthen the position of today’s BRICs and other low-income countries vis a vis the rest of the world?

The answer I would contend could lie in by making a start to changes in regional trading arrangements on continents like that of Africa and Latin America: arrangements modelled on the European Payments Union of 1950 and discussed by Amato and Fantacci in their book: The End of Finance.

I propose that change could begin with an African Payments Union

Images Money - Dollar. Flickr.

As I write, the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) is preparing a ground offensive on Rafah, Palestine . PM Netanyahu has warned for months that such an offensive was imminent. The consensus view was that US pressure was all that held the IDF back from another slaughter of innocents; a battle that would not lead to the release of hostages, and would ultimately strengthen Hamas.

Then a US-sponsored deal – overseen by CIA director William J. Burns – accepted by Hamas, was rejected by Israel.

The consensus view was wrong. Israel, against the apparent advice of the United States president, proceeded defiantly with an attack bound to kill and maim many thousands more innocent civilians, including children and hostages – and to threaten the security of the wider region.

So far, so fairly predictable. Except this – from a professor of American history:

Over the last 130 years there was, and is no situation anywhere in the world where the mighty US of A has not used its leverage “to shape the behaviour of others.”

Israel is ranked way down the global economy in terms of size, population and GDP, and is dependent on the US for military aid. “Shaping its behaviour” should, theoretically, be easier. The country has a population of just 10 million people (not much bigger than the population of London); spends $26bn on the military and has an economy of just half a trillion dollars ($525bn) – according to the World Bank. Contrast that with the US with an annual GDP of $25 trillion and with the world’s highest military expenditure of $916 billion; and a population of 330 million. And to crown its power the US is issuer of the world’s reserve currency: the US dollar.

Yet the Israeli state has succeeded in subordinating the mighty United States of America to its murderous will.

The result is that at a time when the war on Palestine poses a grave threat not only to Palestinians in Gaza and on the West Bank; not only to the security of the Israeli people, but also to the region as a whole

the US has no plans to use its vast leverage ..to deliver even an ounce of peace and justice.

America’s Waning Power – Is It Real?

Given these developments, the United States appears weak, even impotent. This has excited talk of American imperial decline, and of the inevitable demise of the world’s reserve currency, the US dollar.

I am frankly, sceptical of such speculation. The US economy and its currency are mighty powerful – and not easily displaced.

Nevertheless it is important to pay attention to these matters, because we are all affected – albeit differentially – by the power of the US economy, and by the strength or weakness of the US dollar and its use in currency and commodity trading.

Poor countries suffer the most. They are victims (and beneficiaries) of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy (interest rates and Quantitative Easing (QE)) and on the strengthening or weakening of the US dollar; a currency in which they are obliged to borrow, and to buy and sell essential commodities (like food, medicines and energy).

Many low and middle-income countries are debating whether the US dollar, and therefore US power over the global economy, can be displaced? And if so, would that mean turning to, and relying on another reserve currency, like the Chinese yuan, or the Russian ruble?

That debate will soon hit the brick wall of realpolitik. Choosing an alternative national currency as the world’s reserve currency would simply mean choosing an alternative hegemon to that of the United States.

Instead of an alternative currency; or even multiple currencies, countries should argue for a change to the international system – and an end to dependence on a single hegemonic currency – and to the chaotic trading arrangements that hurt all countries – including the United States.

Instead countries of the majorityworld should argue for the establishment of a far more neutral and independent International Clearing Union – as a way of settling international payments – along the lines proposed by John Maynard Keynes in 1944.

Because there is so little knowledge or understanding of Keynes’s proposal for a clearing union, what follows will briefly outline the current context of the de-dollarisation debate, and then the principles of Keynes’s Clearing Union and the implications for BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, China, India and South Africa).

This will be followed, a day later, with a post on the special, but urgent case: the need for an African Payments Union.

A gentle warning: its fascinating, but a little bit nerdy.

The context: the market-driven global economy in 2024

Today’s economy can be characterised as one almighty, and badly entangled mess.

Comparable perhaps to the mess that is the world’s dirty, carbonised atmosphere.

This mess is due to a) the absence of effective state management of the international financial (and eco) system; b) the mobility and volatility of speculative capital; c) leading to obscene levels of inequality – both within and between countries; and d) by trade and capital account imbalances – a consequence of financial and trade deregulation, over-production and under consumption – all leading to trade wars.

Since early in the 1960s when Wall St financiers began to dismantle the Bretton Woods architecture in earnest, management of trade, currency, commodity and money markets was gradually wrenched away from states.

That transfer from public (democratic) authority to private authority over the world economy, has immense implications for states wishing to tackle e.g. inequality; unemployment; public services, but also climate and ecosystem breakdown.

The de-dollarisation debate

This is the chaotic market-driven context in which a range of alternatives to dollar dominance are currently debated by countries of the global majority.

The angry de-dollarisation debate is prompted in part by the freezing of half of Russia’s central bank gold and foreign exchange reserves first by Europe, and then the United states in March 2022. It was coupled with the decision to disconnect Russian banks from the Belgium-based Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

Two years later at a special sitting on Saturday, 20 April, 2024, the US Congress passed a foreign aid package that would permit the Biden administration to confiscate $6 billion of Russian assets in US banks and transfer the proceeds to Ukraine.

The law contains policy provisions under which (i) the statute of limitations for US sanctions violations would be doubled; (ii) frozen Russian state-owned assets could be seized and used to support Ukraine, (iii) additional sanctions would be imposed on Russia, Iran, and Hamas; and (iv) data brokers would be prohibited from transferring personally identifiable sensitive data of US individuals to foreign adversaries.

The confiscation of state assets is an extraordinary development for a capitalist economy that regards property rights as almost sacred; and that promotes a ‘rules-based international order.’

The majority world’s angry response

Angry Chinese, African and Latin American leaders responded quickly. If the United States can seize Russia’s assets held in their trust at e.g. the Federal Reserve or the ECB, they asked, what stops the US from seizing the assets of any other state they disapproved of?

As Robert Greene of the Carnegie Endowment Fund reports, South Africa’s President Ramaphosa expressed concern that

global financial and payment systems are increasingly being used as instruments of geopolitical contestation.

At the April 2023 BRICS summit, where Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were invited to join the bloc, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva asked (to thunderous applause):

“Why can’t we do trade based on our own currencies? Who was it that decided that the dollar was the currency after the disappearance of the gold standard?”

BRICS finance ministers and central bankers were tasked by the 2023 BRICs summit to report back the following year on the question of local currencies’ use and payments infrastructure, according to Reuters. Later, in November 2023, a Leading Chinese Communist Party (CCP) political journal stated that recent U.S. monetary policy choices created a “dollar tide” that

seizes the wealth of other countries and forces developing countries to bear the huge economic losses and financial risks brought about by the hegemony of the dollar.

As a result of these concerns China’s renminbi is increasingly used for cross-border payments – even while such payments are limited relative to the U.S. dollar. It’s use in China’s cross-border transactions grew from around 20 per cent to approximately 50 percent between 2016 and 2022, according to Bloomberg. Russia’s finance minister explained to the TASS news agency on 19 September, 2023 that 70 percent of China-Russia trade was settled in renminbi during the first three quarters of 2023. In May 2023, Russian authorities were reportedly considering using the renminbi to facilitate trade with Iran. In the meantime, it is reported that the Russian central bank is encouraging countries in the use of its alternative to SWIFT for transmitting financial messages: SPFS.

The alternative: An International Clearing Union: what is it?

An International Clearing Union (ICU) would end dependence on any one currency; and would manage the payments part of the world’s trading system.

Here’s how to think about it.

A Clearing Union system is comparable to the domestic, commercial banking system which, with the help of the central bank, manages payments between buyers and sellers undertaking business transactions and borrowing or paying for those via a bank. The difference is that the buyers and sellers in the ICU would be nations, channelling the cross-border transactions of their citizens – individuals and corporations.

To understand the management of a clearing union, think of the central bank’s role within a commercial banking system. As we borrow, deposit, or withdraw money from banks, bankers are required to ‘balance their books’. on a daily basis. (Managing stocks and flows of money in and out of banks, is hard, and often not profitable.)

Central bank reserves can’t be used outside of the banking system. The central bank dispenses or absorbs these reserves to keep the whole commercial, licensed banking system stable as it manages thousands of transactions every day.

Of course its much more complicated than that – time and interest rates play a big part – but you get the big picture.

In just the same way an international institution – say the Bank for International Settlements (BIS, the Big Daddy of central banks) – based in Basel, Switzerland, could play the role of ‘central banker’ or supervising authority to nations trading with each other. Trade will be undertaken in their own currencies and the foreign exchange arrangements settled by the supervising authority, if it is the BIS.The authority’s actions would be transparent; and would keep tabs on surpluses and deficits within the trading system. It would do so in the neutral way a central bank treats the commercial banks within its domain. Keynes envisioned that such a neutral institution would have an apolitical structure – which is what central banks are supposed to have. Unlike the IMF – which has a highly politicised board of management – central banks do not discriminate against debtor banks within its system; or force only debtor banks to restore balance and make the necessary adjustment. It treats both debtor and creditor banks the same. After all, imbalances are inevitable, and central to the very nature of the banking business. Nor do central banks consciously set economic terms and conditions that would harm the economic stability of the banks within its care, as the IMF does.

Jane D’Arista – an expert on the ICU, expanded on these points in a book I edited in 2003: The Real World Economic Outlook. She explained that

…..an importer in country A would pay for machinery from country B by writing a check on his bank account in his own currency. The seller in country B would deposit the check in his bank and receive credit in his own currency at the current rate of exchange between the two currencies. This would be possible because of the existence of an international clearing process that would route the check from the commercial bank to the central bank in country B and from there to the international clearing agency (ICA).

At the end of the day, the ICA would net all checks exchanged between two countries and pay the difference by debiting or crediting their reserve accounts.

The process is simple but it does imply certain rules. It would require that all commercial banks receiving foreign payments exchange them for domestic currency deposits with their central banks. The central banks, in turn, would be required to deposit all foreign payments with the ICA. The result would be that all international reserves would be held by the ICA and that the process of debiting and crediting payments against countries’ reserve accounts would provide the means for determining changes in exchange rates. As in national systems where the level of required reserves is determined at weekly or bi-weekly intervals, such a structure would greatly reduce the exchange rate volatility that currently plagues the system.

An ICUwould not need a common currency to function, or if it did, that currency would only be used within and between members of the clearing union itself.

The importance of balancing the international trading system

By keeping accounts of payments in and out of the ICU and clearing transactions between trading nations, the ICU could help ensure member nations don’t build up deficits (overdrafts) but also surpluses – and that they always pay their dues.

Both trading debtors and creditors would be penalised – with higher rates of interest on outstanding payments, or on surpluses. That is because, in macroeconomic terms, one country’s trade surplus is another’s trade deficit. It may seem counter-intuitive, but trade surpluses are as harmful to international trade stability as deficits.

The policies that help build up trade surpluses are known as ‘beggar thy neighbour’ policies – where one country solves its domestic economic problems by dumping (sic) on another. And so, within a clearing union, both debtor (deficit) and creditor (surplus) countries would have to adjust, to restore balance to the world’s trading system. Trade surplus countries (like China, Kuwait or Germany) would do this by buying more from trade deficit countries (like the US, the United Kingdom or South Africa) to help restore stability to the international system as a whole.

Today the international trading system is neither supervised nor managed. Instead there are vast imbalances between surplus and deficit countries, and these in turn are the result of a) imbalances in the domestic economy and b) a cause of trade wars. (That is why Klein and Pettis’s book title: Trade Wars are Class Wars – is so pertinent.)

Surely such ‘system change’ is pie-in-the-sky?

Now many have argued that to replace the US dollar’s reserve status with an international clearing union would be nigh impossible. But we disagree. The ‘we’ referred to here includes two brilliant Italian economists, Massimo Amato and Luca Fantacci and myself. Back in 2019 we wrote in Open Democracy about an important precedent: an inter-national clearing union that had worked most successfully in recent history: the European Payments Union (EPU) of the 1950s. Amato and Fantacci explain how – in contrast to the Marshall Plan – the EPA had been successful in restoring economic health to a devastated, post-war Europe.

The European Payments Union (EPU) was established between 1950 and 1958.

The EPU made it possible for each country to finance its current account deficits without relying on the vagaries of capital liquidity provided by international financial markets, by providing a ‘clearing centre’. The country’s position was recorded as a net position in relation to the clearing centre itself, and thus as a multilateral position in relation to all the other countries.

A quota was set for each country corresponding to 15% of its trade with the other countries in the Union. Credit and debit balances could not exceed the respective quotas. The system therefore set a limit on the accumulation of debts or deficits with the clearing centre, and provided debtors with an incentive to converge towards equilibrium with their trading partners. The EPU also exerted strong pressure on creditor countries which, like Germany and Holland today, failed to raise imports and cut their surpluses.

The result was an extraordinary, export-driven expansion in production, in Germany and Italy in particular, and the liberalisation of trade not only within the EU, but also well beyond.

But what was most extraordinary was that this expansion of trade came along with rising employment and welfare in each partner country: the EPU was a part of a superstructure that provided countries with more autonomy to foster an economy led by domestic demand.

In other words: the Marshall Plan merely provided liquidity – i.e. cash – which at a time of European economic devastation was largely used by Europeans to buy American goods. That suited Americans very well, and allowed the country to maintain high levels of wartime production. However, it did not help Europe recover production, employment and income at home. The EPA by contrast, provided European countries with the kind of ‘overdrafts’ that permitted them to begin investing, producing and trading their own goods and services – which in turn generated employment and income – at home.

Unfortunately the system was dismantled by the ideology of ‘free markets’ and untrammelled capital flows…the very system that has bestowed today’s chaotic, divisive and unbalanced global economy on us all.

Which way forward?

Given all of the above, how could interim changes to the monetary system, along the lines proposed by Keynes, be made to ease global trade tensions? And how could such changes strengthen the position of today’s BRICs and other low-income countries vis a vis the rest of the world?

The answer I would contend could lie in by making a start to changes in regional trading arrangements on continents like that of Africa and Latin America: arrangements modelled on the European Payments Union of 1950 and discussed by Amato and Fantacci in their book: The End of Finance.

I propose that change could begin with an African Payments Union

No comments:

Post a Comment