The Religious Composition of the World’s Migrants

Christians are the largest migrant group, but Jews are most likely to have migrated

Migration has grown steadily in recent decades. Today, more than 280 million people, or 3.6% of the world’s population, are international migrants – meaning they live outside their country of birth.

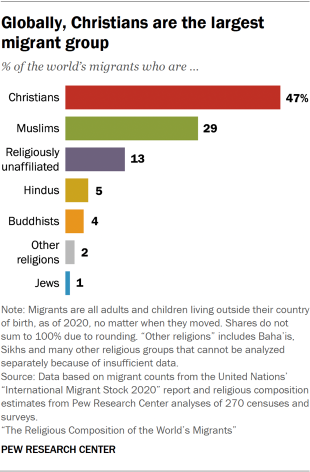

Christians made up an estimated 47% of all people living outside their country of birth as of 2020, the latest year for which global figures are available, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of United Nations data and 270 censuses and surveys.

Muslims accounted for 29% of all living migrants, followed by Hindus (5%), Buddhists (4%) and Jews (1%).

The religiously unaffiliated – i.e., those who say they have no religion, or who identify as atheist or agnostic – represented 13% of all the people who have left their country of birth and are now living elsewhere.1

Over the past three decades, the total number – or stock – of people living as international migrants has increased by 83%, outpacing global population growth of 47%.

This report focuses on stocks rather than flows of migrants. We are counting all adults and children who now live outside their countries of birth, no matter when they left.

We are not trying to estimate how many move in a single year.

While the religious makeup of migration flows can change drastically from year to year – due to wars, economic crises and natural disasters – the total stock of migrants changes more slowly, reflecting patterns that have accumulated over time.

The religious makeup of all international migrants has remained relatively stable since 1990.

Our analysis finds:

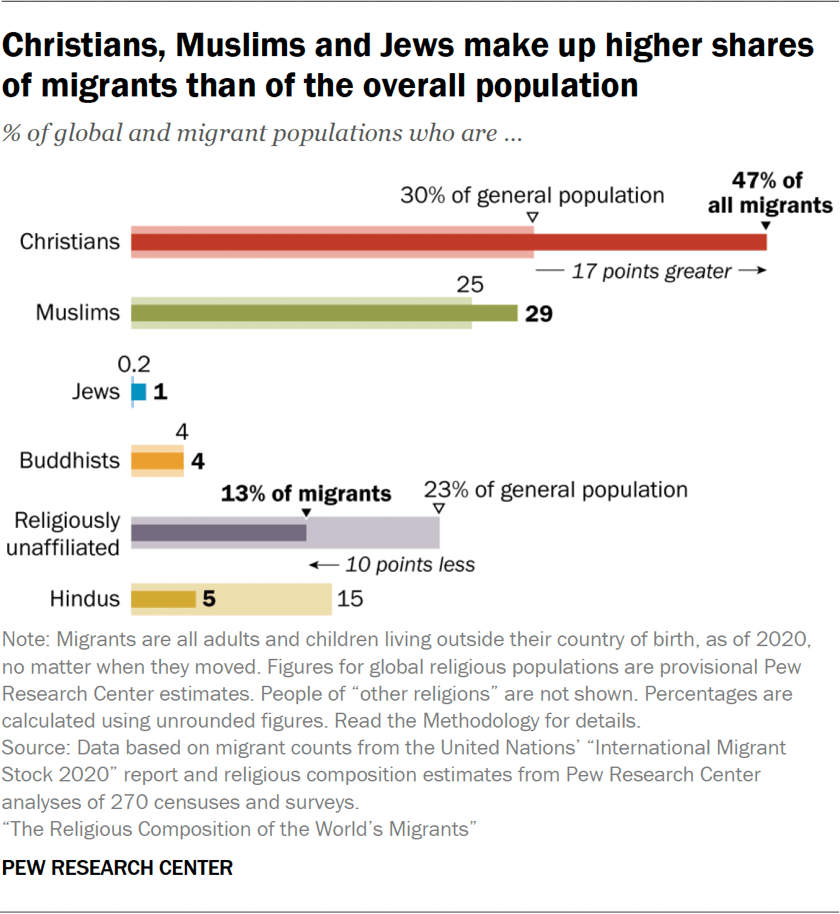

- Christians make up a much larger share of migrants (47%) than they do of the world’s population (30%). Mexico is the most common origin country for Christian migrants, and the United States is their most common destination.

- Muslims account for a slightly larger share of migrants (29%) than of the world’s population (25%). Syria is the most common origin country for Muslim migrants, and Muslims often move to places in the Middle East-North Africa region, like Saudi Arabia.

- People without a religion make up a smaller percentage of migrants (13%) than of the global population (23%).2 China is the most common origin country for religiously unaffiliated migrants, and the U.S. is their most common destination.

- Hindus are starkly underrepresented among international migrants (5%) compared with their share of the global population (15%). India is both the most common country of origin and the top destination for Hindu migrants.

- Buddhists make up 4% of the world’s population and 4% of its international migrants. Myanmar (also called Burma) is the most common origin country for Buddhist migrants, while Thailand is their most common destination.

- Jews form a much larger share of migrants (1%) than of the world’s population (0.2%). Israel is the most frequent origin country among Jewish migrants and also their top destination.

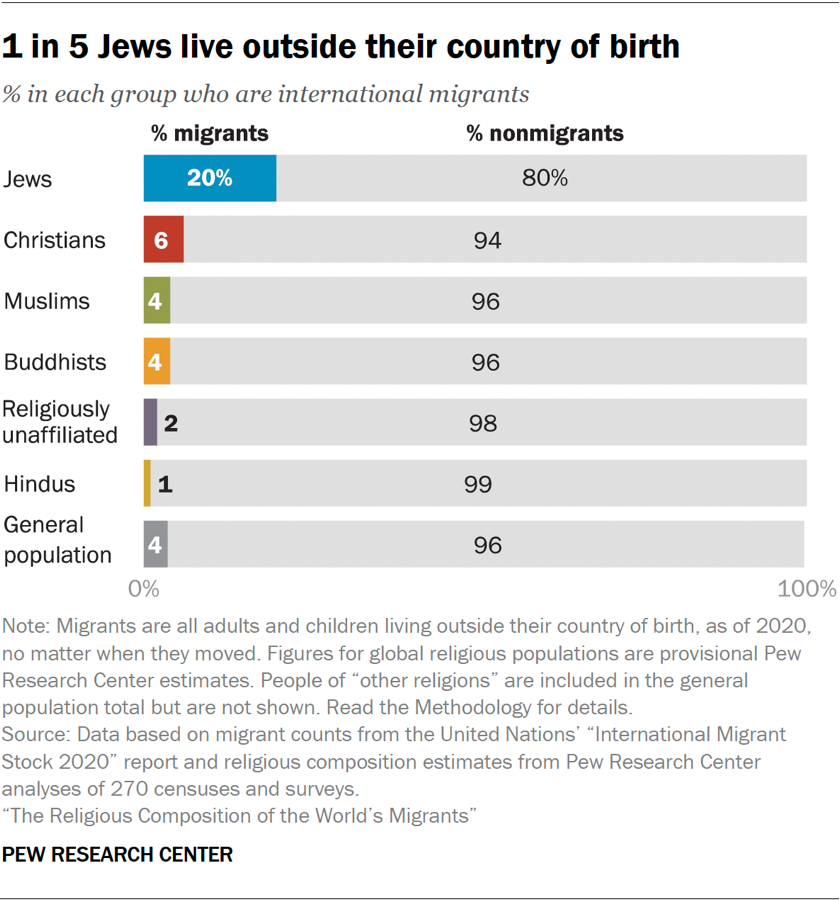

- Of the major religious groups, Jews are by far the likeliest to have migrated. One-in-five Jews reside outside of their country of birth, compared with smaller shares of Christians (6%), Muslims (4%), Hindus (1%), Buddhists (4%) and the religiously unaffiliated (2%).

How religion is connected with migration

People move internationally for many reasons, such as to find jobs, get an education or join family members. But religion and migration are often closely connected.

Many migrants have moved to escape religious persecution or to live among people who hold similar religious beliefs. Often people move and take their religion with them, contributing to gradual changes in their new country’s religious makeup. Sometimes, though, migrants shed the religion they grew up with and adopt their new host country’s majority religion, some other religion or no religion.3

While the migration patterns of religious groups differ, the groups in this analysis also have a lot in common. For example, migrants frequently go to countries where their religious identity is already prevalent: Many Muslims have moved to Saudi Arabia, while Jews have gravitated toward Israel. Christians and religiously unaffiliated migrants have the same top three destination countries: the U.S., Germany and Russia.

And, regardless of their religion, migrants often move from relatively poor or dangerous places to countries where they hope to find prosperity and safety.

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center analysis of international migrants around the world. The study is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which seeks to understand global religious change and its impact on societies.

The rest of this report contains chapters on:

- Chapter 1: Migrants living in each region

- Chapter 2: Global migration change, 1990-2020

- Chapter 3: Christian migrants around the world

- Chapter 4: Muslim migrants around the world

- Chapter 5: Religiously unaffiliated migrants around the world

- Chapter 6: Hindu migrants around the world

- Chapter 7: Buddhist migrants around the world

- Chapter 8: Jewish migrants around the world

- Geographic spotlights: A closer look at Europe, GCC countries, India and the United States

Migration since 2020

This report relies on UN estimates of stocks of international migrants around the world for 1990, 2020 and every five-year interval between.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic severely restricted travel, causing a precipitous drop in migration. But movement has picked up since, and there have been some sharp shifts in migration flow patterns. For example, emigration from Ukraine has surged due to its war with Russia.

Even though this report does not include very recent migration, we do not expect that recent events have had much impact on the religious composition of migrants overall. Even large flows of people leaving a country become part of much larger stocks of migrants who have already left, and the characteristics of these stocks tend to change very slowly.

Religious composition of the world’s migrants, 1990-2020

This interactive table shows the estimated religious breakdown of immigrants to, and emigrants from, countries and regions of the world. Click the “Living in” button to see how many immigrants have moved into each country and remain there. Click the “Born in” button to see how many emigrants have moved away from each country and are living elsewhere.

You also can choose between counts and percentages (estimated number vs. % of all migrants). And you can toggle between decades to see how much change has occurred over time.

For an explanation of key findings and the methods we used to generate these estimates, read “The Religious Composition of the World’s Migrants.”

Pew Research Center also has estimated the religious composition of each country’s overall population.

- An additional 2% of global migrants belong to “other religions,” an umbrella category that includes Baha’is, Daoists (also spelled Taoists), Jains, Shintoists, Sikhs and adherents of many other religions. This report does not analyze those groups separately because in many countries, censuses and surveys do not provide sufficiently detailed data about them.↩

- This report presents interim estimates of the overall population in each religious group (including migrants and nonmigrants) using data from three Pew Research Center studies: “The Future of World Religions” (projections of religious composition to the year 2020 published in 2015), “Modeling the Future of Religion in America” (2022) and “Measuring Religion in China” (2023). In the future, the Center will produce new estimates of the overall size of religious groups in 2020, based on data sources that have become available in recent years. Read the Methodology for details.↩

- We have limited data on global patterns of religious switching after migration. Some studies have found evidence of considerable switching among migrants from China, who may join new religious communities as part of the process of integrating into their new home countries. Read, for example, Skirbekk, Vergard, Éric Caron Malenfant, Stuart Basten and Marcin Stonawski. 2012. “The religious composition of the Chinese diaspora, focusing on Canada.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Also refer to Yang, Fenggang. 1999. “Chinese Christians in America: Conversion, assimilation, and adhesive identities.”↩

No comments:

Post a Comment