By Paul Wallis

October 23, 2024

DIGITAL JOURNAL

President Joe Biden's administration is banning new drilling over 40 percent of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, a region important for polar bears - Copyright POLAR BEARS INTERNATIONAL/AFP/File Steven C. AMSTRUP

The last time the Gulf Stream went on holiday during the Ice Age, North America and northern Europe went under about a mile of ice. What is now Britain became uninhabitable even for Ice Age hunters for a while.

That’s the scenario for 2025 and beyond if the Gulf Stream goes.

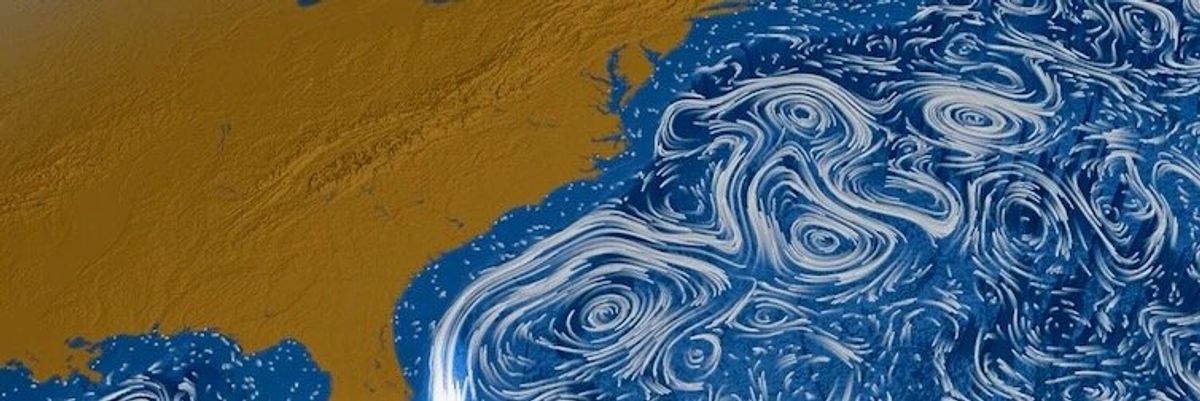

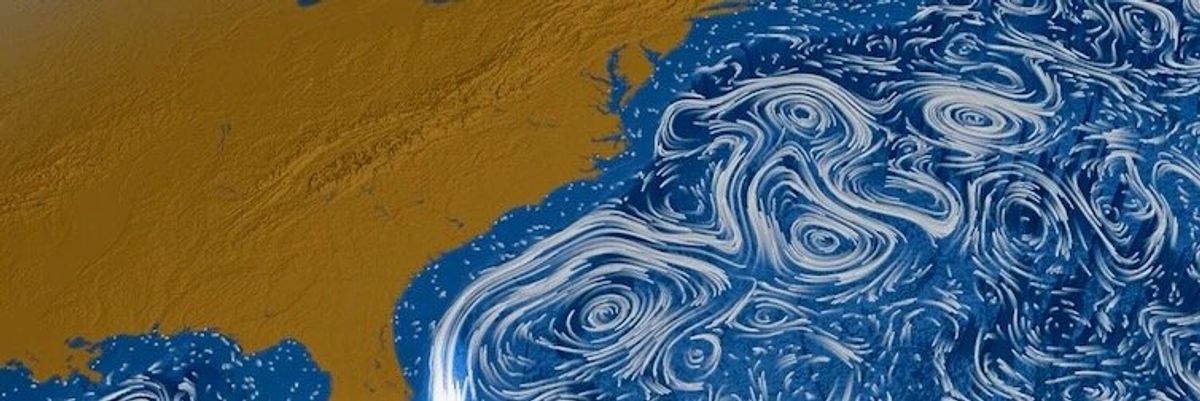

Here you’ll find images and thermal mapping of the Gulf Stream collapse. You’ll note that some of these images are quite old. The data isn’t new or even particularly unusual. It’s just gruesome.

The idea that it could happen almost immediately is very new. It’s also a major professional scientific commitment that’s unusual given the state of the human race at the moment.

Climate scientists are typically wary of anything that could be called “alarmist”, with good reason. The most important of those reasons is peer review, not unqualified babble from PR firms. Off-the-wall predictions can get buried and careers destroyed in seconds by peer review. That’s not happening this time.

No less than 44 top scientists are calling for urgent action. In the current political global stupor, that’s asking a lot. It’s also taking a very high profile on a politically contentious issue. Thankless isn’t the word, but they’ve made their statements.

It’s reached the point where even the pessimists are worried. The question of a collapse of the Gulf Stream, which circulates warm water through the Atlantic, isn’t actually new. Now they’re saying it could happen as soon as next year. The Gulf Stream and its wider framework, called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), look pretty grim.

Well, could it happen?

Maybe.

In recent years, the Gulf Stream has been looking more like a scrambled egg driving without a GPS. The thermodynamics of the northern Atlantic Ocean are complex and massive.

This is where warm southerly currents bump into the Arctic currents and the temperature differences cause major clashes seasonally. Hurricanes are the common events around this time of year.

What happens if the Gulf Stream stops isn’t under any sort of debate. The North freezes. Prehistory is unequivocal about that issue. A shutdown of the Gulf Stream is far more drastic and supposedly could last for centuries.

NOTE: There is still an “if and when” to this scenario.

The problem is that it’s looking far more likely. It has happened before. Greenland was ice-free in prehistory and then froze over. This is how.

The theory is that warming and cooling happen alternately and sometimes suddenly. There’s a reverse cycle to any climate cycle. The current situation is hardly encouraging in that regard. It means freezing or boiling at the extremes of temperature ranges.

Polar phenomena can also push the buttons for climate. The jet streams sometimes look more like pretzels than their usual patterns. If you remember the big ice storms of recent years, they’re a major factor. Add to that an “attempted Ice Age” due to the Gulf Stream going on leave, and you can see that extreme weather is not at all out of the ballpark.

Odd as it is for human reality to get any media coverage at all, this is big enough to rattle even the most apathetic media. It seems that even the Saints of Sycophancy pay attention to Ice Ages. Particularly if it could happen almost tomorrow.

Perhaps they’ll even grow vocabularies and spines and walk erect one day. Can’t wait to see the chat shows when that happens.

The bottom line here has nothing to do with selective ignorance, for a change. Anybody who’s ever used a coloring book or a crayon should be able to see the big thermal variations over time.

This is not an academic exercise.

___________________________________________________________

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this Op-Ed are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Digital Journal or its members.

'Serious risk' of vital ocean current collapse by 2100, warn scientists

Olivia Rosane

Olivia Rosane

, Common Dreams

October 25, 2024

Ocean currents are shown in the North Atlantic. (Image: NOAA)

A group of 44 climate scientists from 15 different countries warn there is a "serious risk" that soaring global temperatures will trigger the "catastrophic" collapse of a crucial system of ocean currents—and possibly sooner than established estimates considered likely.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, moves warm water up from the tropics to the North Atlantic, where it sinks and cools before returning south. It is, as letter signatory and oceanographer Stefan Rahmstorf toldThe Guardian, "one of our planet's largest heat transport systems." If it collapsed, it could lower temperatures in some parts of Europe by up to 30°C.

That's why the scientists sent a letter to the Council of Nordic Ministers over the weekend urging them to take action to understand and prevent a potential collapse.

"A string of scientific studies in the past few years suggests that this risk has so far been greatly underestimated," the scientists wrote. "Such an ocean circulation change would have devastating and irreversible impacts especially for Nordic countries, but also for other parts of the world."

In the letter, the scientists detailed some of the potential "catastrophic" impacts of such a collapse, including "major cooling" in northern Europe, extreme weather, and changes that would "potentially threaten the viability of agriculture in northwestern Europe."

One study cited in the letter shows that London could cool by 10°C and Bergen, Norway by 15°C.

"If Britain and Ireland become like northern Norway, (that) has tremendous consequences. Our finding is that this is not a low probability," Peter Ditlevsen, a University of Copenhagen professor who signed the letter, toldReuters. "This is not something you easily adapt to."

Globally, the scientists said, the end of AMOC could cause the ocean to absorb less carbon dioxide, thereby increasing its presence in the atmosphere. It could also further augment sea-level rise along the U.S. Atlantic coast and alter tropical rainfall patterns.

The most recent synthesis report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expressed "medium confidence" that the current would not cease functioning before 2100. Since its publication in March 2023, however, a rash of studies have come out upping the risk.

"Given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimize this risk."

A Nature Communications study, also published last year, looked at 150 years of temperature data and determined with 95% confidence that AMOC would collapse between 2025 and 2095 if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise as currently predicted.

Another, published in Science Advances in February, concluded that AMOC was currently "on route to tipping."

There are already signs that AMOC has begun to stall over the last six to seven decades, Rahmstorf told The Guardian, such as the cold blob in the North Atlantic that is defying global warming trends. The water in North Atlantic is also becoming less salty due to meltwater from the Greenland ice sheets and increased precipitation due to climate change. Less salty water is lighter and does not sink, interrupting the process that makes AMOC flow.

"It is an amplifying feedback: As AMOC gets weaker, the subpolar oceans gets less salty, and as the oceans gets less salty then AMOC gets weaker," Rahmstorf explained. "At a certain point this becomes a vicious circle which continues by itself until AMOC has died, even if we stop pushing the system with further emissions."

"The big unknown here—the billion-dollar question—is how far away this tipping point is," Rahmstorf said.

The scientists acknowledged that the chance of the AMOC tipping "remains highly uncertain."

They continued:

The purpose of this letter is to draw attention to the fact that only 'medium confidence' in the AMOC not collapsing is not reassuring, and clearly leaves open the possibility of an AMOC collapse during this century. And there is even greater likelihood that a collapse is triggered this century but only fully plays out in the next.

Given the increasing evidence for a higher risk of an AMOC collapse, we believe it is of critical importance that Arctic tipping point risks, in particular the AMOC risk, are taken seriously in governance and policy. Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimize this risk.

To respond to this threat, the scientists urged the council—a group that includes Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Åland—to launch a study of the risk posed to these countries by an AMOC collapse and to take measures to counter that risk.

"This could involve leveraging the strong international standing of the Nordic countries to increase pressure for greater urgency and priority in the global effort to reduce emissions as quickly as possible, in order to stay close to the 1.5°C target set by the Paris agreement," they wrote.

Johan Rockström, a letter signatory who leads the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, wrote on social media that global politics, "particularly in [the] Nordic region, can no longer exclude [the] risk of AMOC collapse."

And there is one way that political leaders can stave off such a collapse, as well as other climate tipping points, according to Rahmstorf.

"This is all driven mainly by fossil fuel emissions and also deforestation, so both must be stopped," he told The Guardian. "We must stick to the Paris agreement and limit global heating as close to 1.5°C as possible."

October 25, 2024

Ocean currents are shown in the North Atlantic. (Image: NOAA)

A group of 44 climate scientists from 15 different countries warn there is a "serious risk" that soaring global temperatures will trigger the "catastrophic" collapse of a crucial system of ocean currents—and possibly sooner than established estimates considered likely.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, moves warm water up from the tropics to the North Atlantic, where it sinks and cools before returning south. It is, as letter signatory and oceanographer Stefan Rahmstorf toldThe Guardian, "one of our planet's largest heat transport systems." If it collapsed, it could lower temperatures in some parts of Europe by up to 30°C.

That's why the scientists sent a letter to the Council of Nordic Ministers over the weekend urging them to take action to understand and prevent a potential collapse.

"A string of scientific studies in the past few years suggests that this risk has so far been greatly underestimated," the scientists wrote. "Such an ocean circulation change would have devastating and irreversible impacts especially for Nordic countries, but also for other parts of the world."

In the letter, the scientists detailed some of the potential "catastrophic" impacts of such a collapse, including "major cooling" in northern Europe, extreme weather, and changes that would "potentially threaten the viability of agriculture in northwestern Europe."

One study cited in the letter shows that London could cool by 10°C and Bergen, Norway by 15°C.

"If Britain and Ireland become like northern Norway, (that) has tremendous consequences. Our finding is that this is not a low probability," Peter Ditlevsen, a University of Copenhagen professor who signed the letter, toldReuters. "This is not something you easily adapt to."

Globally, the scientists said, the end of AMOC could cause the ocean to absorb less carbon dioxide, thereby increasing its presence in the atmosphere. It could also further augment sea-level rise along the U.S. Atlantic coast and alter tropical rainfall patterns.

The most recent synthesis report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expressed "medium confidence" that the current would not cease functioning before 2100. Since its publication in March 2023, however, a rash of studies have come out upping the risk.

"Given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimize this risk."

A Nature Communications study, also published last year, looked at 150 years of temperature data and determined with 95% confidence that AMOC would collapse between 2025 and 2095 if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise as currently predicted.

Another, published in Science Advances in February, concluded that AMOC was currently "on route to tipping."

There are already signs that AMOC has begun to stall over the last six to seven decades, Rahmstorf told The Guardian, such as the cold blob in the North Atlantic that is defying global warming trends. The water in North Atlantic is also becoming less salty due to meltwater from the Greenland ice sheets and increased precipitation due to climate change. Less salty water is lighter and does not sink, interrupting the process that makes AMOC flow.

"It is an amplifying feedback: As AMOC gets weaker, the subpolar oceans gets less salty, and as the oceans gets less salty then AMOC gets weaker," Rahmstorf explained. "At a certain point this becomes a vicious circle which continues by itself until AMOC has died, even if we stop pushing the system with further emissions."

"The big unknown here—the billion-dollar question—is how far away this tipping point is," Rahmstorf said.

The scientists acknowledged that the chance of the AMOC tipping "remains highly uncertain."

They continued:

The purpose of this letter is to draw attention to the fact that only 'medium confidence' in the AMOC not collapsing is not reassuring, and clearly leaves open the possibility of an AMOC collapse during this century. And there is even greater likelihood that a collapse is triggered this century but only fully plays out in the next.

Given the increasing evidence for a higher risk of an AMOC collapse, we believe it is of critical importance that Arctic tipping point risks, in particular the AMOC risk, are taken seriously in governance and policy. Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimize this risk.

To respond to this threat, the scientists urged the council—a group that includes Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Åland—to launch a study of the risk posed to these countries by an AMOC collapse and to take measures to counter that risk.

"This could involve leveraging the strong international standing of the Nordic countries to increase pressure for greater urgency and priority in the global effort to reduce emissions as quickly as possible, in order to stay close to the 1.5°C target set by the Paris agreement," they wrote.

Johan Rockström, a letter signatory who leads the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, wrote on social media that global politics, "particularly in [the] Nordic region, can no longer exclude [the] risk of AMOC collapse."

And there is one way that political leaders can stave off such a collapse, as well as other climate tipping points, according to Rahmstorf.

"This is all driven mainly by fossil fuel emissions and also deforestation, so both must be stopped," he told The Guardian. "We must stick to the Paris agreement and limit global heating as close to 1.5°C as possible."

Dangers of Atlantic Ocean current collapse have been ‘greatly underestimated’, scientists warn

Euronews Green

Thu, October 24, 2024

Dangers of Atlantic Ocean current collapse have been ‘greatly underestimated’, scientists warn

Scientists have warned that the dangers of the collapse of a key Atlantic Ocean current that helps regulate the Earth's climate have been "greatly underestimated".

In an open letter published earlier this week, 44 leading climate scientists from 15 countries said that the collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) would have devastating and irreversible impacts. They write that the risks require urgent action from policymakers.

The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report says there is "medium confidence" that the AMOC will not collapse abruptly by 2100. But the group of experts says this is an underestimate.

"The purpose of this letter is to draw attention to the fact that only 'medium confidence' in the AMOC not collapsing is not reassuring, and clearly leaves open the possibility of an AMOC collapse during this century," they write in the open letter.

Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimise this risk.

"Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimise this risk."

Related

‘Unlimited growth is an illusion’: Scientists urge fossil fuels phase down as Earth at tipping point

COPs are struggling to keep 1.5C alive. Are there better forms of climate diplomacy?

The letter is addressed to the Nordic Council of Ministers, an intergovernmental forum which aims to promote cooperation among the Nordic countries. It urges policymakers to consider the risks posed by an AMOC collapse and put pressure on governments to stay within Paris Agreement targets.

What is the Atlantic Ocean Circulation?

The AMOC is an important system of ocean currents. It transports warm water, carbon and nutrients north via the Atlantic Ocean where the water cools and sinks into the deep.

This helps to distribute energy around the planet, moving heat through the ocean like a conveyor belt and regulating our climate.

Warm water - more salty due to evaporation - flows north on the surface of the ocean keeping Europe milder than it would otherwise be. When this water cools it sinks because its high salinity increases its density. It then flows back to the southern hemisphere along the bottom of the ocean.

But studies of past episodes of dramatic cooling in Europe over the last 100,000 years suggest melting ice sheets could weaken the AMOC due to changes in salinity and temperature.

Fresh water reduces the saltiness - and therefore the density of the water- on the surface of the ocean. This means less of the surface water sinks, potentially slowing the flow of the current.

Are we heading for a catastrophic tipping point?

Some research has suggested that climate change may be slowing the flow of the current. One study from 2023, based on sea surface temperatures, suggested that a complete collapse could happen between 2025 and 2095.

There is huge uncertainty about how, when or even if this ‘tipping point’ could actually happen, however, and modelling the scenario is tricky. Most previous computer simulations that showed a collapse involved adding huge, unrealistic quantities of fresh water all at once.

In February this year, scientists from Utrecht University in the Netherlands used a complex climate model to simulate the collapse of the AMOC and discovered that it could be closer than previously thought.

Related

A La Niña event is likely coming to Europe: What does it mean for weather this winter?

‘No to the reservoirs’: Why are locals against this plan to save the drought-hit Panama Canal?

The Dutch team used a supercomputer to carry out the most sophisticated modelling so far to look for warning signs of this tipping point. They added water gradually, finding that a slow decline could eventually lead to a sudden collapse over less than 100 years.

Previously, the paper published in February said, an AMOC tipping point was only a “theoretical concept” and its authors found that the rate at which the tipping of this vital current occurred in their modelling was "surprising".

Large icebergs near the town of Kulusuk, in eastern Greenland. - Felipe Dana/Copyright 2019 The AP. All rights reserved.

But researchers had to run the simulation for more than 2,000 years to get this result and still added significantly more water than is currently entering the ocean as Greenland’s ice sheet melts.

"The research makes a convincing case that the AMOC is approaching a tipping point based on a robust, physically-based early warning indicator," said University of Exeter climate scientist Tim Lenton, who wasn't involved in the research, at the time.

"What it cannot (and does not) say is how close the tipping point is because it shows that there is insufficient data to make a statistically reliable estimate of that."

Lead author of the study, René van Westen also added that there wasn’t enough data to say anything definitive about a potential future AMOC collapse. More research is needed to work out a timeframe - including models that incorporate increasing levels of carbon dioxide and global warming.

“We can only say that we’re heading towards the tipping point and that AMOC tipping is possible.”

We can only say that we’re heading towards the tipping point and that AMOC tipping is possible.

Some of the changes seen in the model before the collapse do, however, correspond with changes we’ve seen in the Atlantic Ocean in recent decades.

“When the AMOC loses stability, as we know from the available reconstructions, it is more likely that abrupt transitions may develop in the future,” van Westen added.

Related

3,000 risk experts and 20,000 citizens name climate change as number one threat facing the world

As England suffers one of its worst ever harvests ever, what could disappear from shop shelves?

Lenton said that we have to "hope for the best but prepare for the worst" by investing in more research to improve the estimate of how close a tipping point is, assess the potential impacts and work out how we can manage and adapt to those impacts.

What would a collapse of the ocean current mean for Europe?

If the AMOC collapses, previous research has shown the resulting climate impacts would be nearly irreversible in human timescales. It would mean severe global climate repercussions, with Europe bearing the brunt of the consequences.

Some parts of Europe could see temperatures plunge by up to 30C. On average, the model shows London cooling by 10C and Bergen by 15C.

The report’s authors say that “no realistic adaptation measures can deal with such rapid temperature changes”.

Temperatures in the southern hemisphere would rise with wet and dry seasons in the Amazon rainforest flipping.

Van Westen also explained earlier this year that it could mean less rainfall and a sea level rise of up to one metre in coastal areas of Europe.

"The overall picture that AMOC collapse would be catastrophic fits with my own group’s recent work showing that it would likely cause a widespread food and water security crisis," according to Lenton.

Euronews Green

Thu, October 24, 2024

Dangers of Atlantic Ocean current collapse have been ‘greatly underestimated’, scientists warn

Scientists have warned that the dangers of the collapse of a key Atlantic Ocean current that helps regulate the Earth's climate have been "greatly underestimated".

In an open letter published earlier this week, 44 leading climate scientists from 15 countries said that the collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) would have devastating and irreversible impacts. They write that the risks require urgent action from policymakers.

The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report says there is "medium confidence" that the AMOC will not collapse abruptly by 2100. But the group of experts says this is an underestimate.

"The purpose of this letter is to draw attention to the fact that only 'medium confidence' in the AMOC not collapsing is not reassuring, and clearly leaves open the possibility of an AMOC collapse during this century," they write in the open letter.

Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimise this risk.

"Even with a medium likelihood of occurrence, given that the outcome would be catastrophic and impacting the entire world for centuries to come, we believe more needs to be done to minimise this risk."

Related

‘Unlimited growth is an illusion’: Scientists urge fossil fuels phase down as Earth at tipping point

COPs are struggling to keep 1.5C alive. Are there better forms of climate diplomacy?

The letter is addressed to the Nordic Council of Ministers, an intergovernmental forum which aims to promote cooperation among the Nordic countries. It urges policymakers to consider the risks posed by an AMOC collapse and put pressure on governments to stay within Paris Agreement targets.

What is the Atlantic Ocean Circulation?

The AMOC is an important system of ocean currents. It transports warm water, carbon and nutrients north via the Atlantic Ocean where the water cools and sinks into the deep.

This helps to distribute energy around the planet, moving heat through the ocean like a conveyor belt and regulating our climate.

Warm water - more salty due to evaporation - flows north on the surface of the ocean keeping Europe milder than it would otherwise be. When this water cools it sinks because its high salinity increases its density. It then flows back to the southern hemisphere along the bottom of the ocean.

But studies of past episodes of dramatic cooling in Europe over the last 100,000 years suggest melting ice sheets could weaken the AMOC due to changes in salinity and temperature.

Fresh water reduces the saltiness - and therefore the density of the water- on the surface of the ocean. This means less of the surface water sinks, potentially slowing the flow of the current.

Are we heading for a catastrophic tipping point?

Some research has suggested that climate change may be slowing the flow of the current. One study from 2023, based on sea surface temperatures, suggested that a complete collapse could happen between 2025 and 2095.

There is huge uncertainty about how, when or even if this ‘tipping point’ could actually happen, however, and modelling the scenario is tricky. Most previous computer simulations that showed a collapse involved adding huge, unrealistic quantities of fresh water all at once.

In February this year, scientists from Utrecht University in the Netherlands used a complex climate model to simulate the collapse of the AMOC and discovered that it could be closer than previously thought.

Related

A La Niña event is likely coming to Europe: What does it mean for weather this winter?

‘No to the reservoirs’: Why are locals against this plan to save the drought-hit Panama Canal?

The Dutch team used a supercomputer to carry out the most sophisticated modelling so far to look for warning signs of this tipping point. They added water gradually, finding that a slow decline could eventually lead to a sudden collapse over less than 100 years.

Previously, the paper published in February said, an AMOC tipping point was only a “theoretical concept” and its authors found that the rate at which the tipping of this vital current occurred in their modelling was "surprising".

Large icebergs near the town of Kulusuk, in eastern Greenland. - Felipe Dana/Copyright 2019 The AP. All rights reserved.

But researchers had to run the simulation for more than 2,000 years to get this result and still added significantly more water than is currently entering the ocean as Greenland’s ice sheet melts.

"The research makes a convincing case that the AMOC is approaching a tipping point based on a robust, physically-based early warning indicator," said University of Exeter climate scientist Tim Lenton, who wasn't involved in the research, at the time.

"What it cannot (and does not) say is how close the tipping point is because it shows that there is insufficient data to make a statistically reliable estimate of that."

Lead author of the study, René van Westen also added that there wasn’t enough data to say anything definitive about a potential future AMOC collapse. More research is needed to work out a timeframe - including models that incorporate increasing levels of carbon dioxide and global warming.

“We can only say that we’re heading towards the tipping point and that AMOC tipping is possible.”

We can only say that we’re heading towards the tipping point and that AMOC tipping is possible.

Some of the changes seen in the model before the collapse do, however, correspond with changes we’ve seen in the Atlantic Ocean in recent decades.

“When the AMOC loses stability, as we know from the available reconstructions, it is more likely that abrupt transitions may develop in the future,” van Westen added.

Related

3,000 risk experts and 20,000 citizens name climate change as number one threat facing the world

As England suffers one of its worst ever harvests ever, what could disappear from shop shelves?

Lenton said that we have to "hope for the best but prepare for the worst" by investing in more research to improve the estimate of how close a tipping point is, assess the potential impacts and work out how we can manage and adapt to those impacts.

What would a collapse of the ocean current mean for Europe?

If the AMOC collapses, previous research has shown the resulting climate impacts would be nearly irreversible in human timescales. It would mean severe global climate repercussions, with Europe bearing the brunt of the consequences.

Some parts of Europe could see temperatures plunge by up to 30C. On average, the model shows London cooling by 10C and Bergen by 15C.

The report’s authors say that “no realistic adaptation measures can deal with such rapid temperature changes”.

Temperatures in the southern hemisphere would rise with wet and dry seasons in the Amazon rainforest flipping.

Van Westen also explained earlier this year that it could mean less rainfall and a sea level rise of up to one metre in coastal areas of Europe.

"The overall picture that AMOC collapse would be catastrophic fits with my own group’s recent work showing that it would likely cause a widespread food and water security crisis," according to Lenton.

No comments:

Post a Comment