AMERIKA

The State of the Left Reflects Our Ambivalence About the State

Heritage Foundation president and key architect of Project 2025 Kevin Roberts recently said, “we are in the process of a second American revolution, which will remain bloodless if the left allows it to be.” We should not mistake the far right for peaceful—but we do need to take these efforts seriously. As Project 2025 shows, the right is indeed plotting a “revolution.” Key to their plans is a strategic focus on seizing control of the state apparatus and using the levers of government to fundamentally transform the United States.

As we fight to defeat the right’s attempted “slow motion coup” over the state apparatus, the left must be as audacious about our own governing agenda, and as strategic in our approach to governance. But this requires leftists to grapple seriously with the question of state power—and unfortunately, many on the left hold confused and contradictory ideas about the state. I should know, because for a long time I did too.

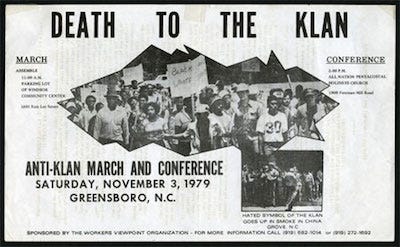

Growing up in my hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina I heard all about the infamous 1979 massacre, when the Ku Klux Klan shot and killed five participants in an anti-klan mobilization organized by the Communist Workers Party/Workers Viewpoint Organization (CWP/WVO). Members of CWP/WVO’s Greensboro chapter lived collectively and operated on the turn-to-industry strategy taken up by many in the New Communist Movement. Their organizing target was the textile industry which had migrated south for a cheaper labor market. Members “salted” by getting jobs at textile mills with the goal of organizing workers there. But plant bosses close to the Klan targeted salts for termination, making it more difficult to effectively organize workplace actions. As a result, CWP/WVO shifted to focus on countering the Klan.

A new local coalition made up of Klansmen and neo-nazis came together, calling itself the United Racist Front (URF). One of their stated goals was to crush CWP/WVO. URF was thoroughly infiltrated by Greensboro police informants as well as FBI and ATF agents who knew of plans to kill specific CWP/WVO members, namely those leading organizing efforts at local textile mills. The two organizations confronted each other at raucous rallies where both came armed.

On the morning of November 3rd, 1979, CWP/WVO members, their families, and community supporters gathered singing in a circle on the front lawn of a housing project for their “Death to the Klan” rally. Police and FBI agents were stationed in unmarked cars up and down the street. A car long caravan of URF members approached the rally. “You wanted the klan, you got em!” a news camera recorded one URF member shouting from an open car window. The caravan stopped. From the lead car, undercover FBI agent George Dorsett fired a pistol in the air. URF members took the signal, calmly exited their cars, and retrieved guns from their trunks. When the shooting was over, five CWP/WVO members were dead and several others wounded. All URF members charged with the murders were acquitted twice, both times by all-white juries.

As a teenager, hearing this story led me toward anarchism. I viewed the state, particularly the repressive apparatus, as the absolute enemy of the people. I got involved with a coalition of anarchists, faith leaders, and community groups which included the Greensboro Black-Brown Unity Coalition, led in-part by former CWP/WVO members, one of whom had lost her husband in the massacre.

The coalition also included the Almighty Latin King and Queen Nation (ALKQN), previously the Latin Kings, a former street gang who put forward a bold new vision for their organization. Renouncing drugs, guns and violence, they became a political force, organizing local gangs together into a peace treaty alliance they referred to as the Paradigm Shift, running for city council, and participating in calls for police reform. The ALKQN’s understanding of itself as a “street organization” aligned with the Black Panther Party’s focus on the lumpenproletariat—specifically, criminal elements. With clear parallels to the Combahee River Collective statement which first defined intersectional feminism politically, they understood the liberation of the most oppressed to be the precondition for all others’ liberation, putting poor Black and Brown workers—formally employed or not—in an objective leadership position.

The nascent coalition organized a caravan of their own up to Washington D.C., where ALKQN, NAACP, NOI and other organizations presented a formal civil rights complaint to the Department of Justice detailing abuses by Greensboro Police, including internal surveillance of Black officers. Three months later, federal agents kicked in the doors of leading ALKQN members early on a cold December morning and dragged their families outside after using stun grenades and wielding assault rifles.

The 13 ALKQN members arrested were charged under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), essentially a prosecutor playbook for going after criminal enterprises like the mob. Jorge Cornell, one of those charged, told me during a jail visit, “if we’re a criminal enterprise, then we’re the poorest criminal enterprise there’s ever been.” Even those critical of the ALKQN understood this to be a politically motivated attack, though some white progressives were uneasy. The parallels were not lost on surviving former CWP/WVO members who took on leadership roles in the ALKQN Legal Defense Coalition.

My role was small. I took kids to softball practice whose parents were now locked up. I sat in court hearings and took rigorous notes. I visited our ALKQN comrades in jail. Ultimately, I saw good people found guilty of a crime they didn’t commit and sentenced to decades in prison.

I was 17 by the time the yearlong ordeal reached its tragic conclusion. The experience only deepened my anarchism. In 2012, I drove down in a smaller caravan to Atlanta for a “fuck the police march” organized by a contingent of ‘insurrectionary anarchists’. Halfway through the march, police attacked. I saw a person carrying the lead banner take a punch to the jaw before entering into a scuffle with the cops. Before I knew what was happening, I received a kick to the chest that knocked me from the middle of the street onto the sidewalk. When I looked up, I saw one of the marchers being choked out by a cop, so I ran over and tried to intervene. From there I was tackled to the ground and my head slammed into the asphalt. I spent the night in jail with one of those arrested and was given a sentence of community service.

These types of experiences hardened my opposition to the state. But coming of age in the heyday of neoliberalism, it wasn’t only anarchist activists who felt deeply skeptical about government. In the aftermath of the Reagan Revolution, social services were gutted and civil rights protections hollowed out, while the repressive components of the state were further weaponized through mass incarceration and criminalization. For many Black, Brown, queer, trans, poor and working class people, “government” came to mean an inadequate and dysfunctional welfare state, along with an all-too-functional police and prison system.

Small wonder that many of us came to think of the state extremely negatively—ironically, one of the very aims of the architects of neoliberalism. Indeed, the Reagan “Revolution” was more accurately a counter-revolution to beat back the limited but significant bulkheads that organized movements of people of color, women and the multiracial working class had won inside the state across the twentieth century. Getting people like me to hate the government was precisely one of its aims.

It took me years of study, struggle and organizing before I realized that the state is not a monolith. Gradually, I came to see it differently—understanding the state, not as our enemy, but rather as one of the things we struggle with our enemies over. In other words, the state should itself be viewed as a terrain of struggle inside which competing factions and blocs of classes vie for power. The balance of power within the state reflects that of the broader society, but also dramatically shapes and impacts it, as different forces use the tools of interconnected state apparatuses to advance or impede their various interests.

The Right has long understood this. Just look at the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025. They plan to fire 50,000 civil servants and replace them with right-wing apparatchiks, strengthen those components of the state already under their control, and weaken or dismantle those aspects (like the Department of Education) that they view as inimically hostile to their interests. Correctly, they understand that the state is not a static entity but a site of contestation, one that can be transformed to advance their aims and interests—or ours.

Many on the Left, however, still hold confused and contradictory ideas about the state. Some imagine “changing the world without taking power,” while others misinterpret the lessons of past revolutions to fantasize about armed struggle against the US government. Meanwhile, factions within DSA argue over whether to prioritize workplace organizing or electoral engagement—a false dichotomy that positions the state as something outside of or opposed to the class struggle, rather than a crucial terrain in and through which struggle plays out.

Even when leftists concede that the state may play a useful role, many of us view the repressive state apparatus, in particular, only as an enemy rather than as a site of struggle. Understandably. The military has historically been a tool of imperialism abroad and for crushing dissent at home. But military personnel themselves are public sector workers with a long history of organized resistance. The military has also been decisive in enforcing mass movement demands during this country’s two most progressive periods:

- After defeating the Confederate States of America, Union troops enforced martial law over and against the will of southern planter elites. This was done to the extent that formerly enslaved Black and poor white workers briefly shared an economic interest with northern capitalists in overthrowing the rule of enslavers in the U.S. South. In that brief time, backed by the military, southern workers replaced the planter aristocracy as executor of the state.

- In the Second Reconstruction of the 1950s and 1960s, mass nonviolent direct action led to large-scale tangible victories for Black Americans and other oppressed groups, leading to overall economic gains for the multi-racial working class. Yet while these victories were won with little to no use of arms, their final success still hinged on military support. In 1957, the National Guard was used to enact the desegregation of Little Rock High School and other public institutions across the south. The two biggest concessions won during that period, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, were both enforced by U.S. troops.

![District of Columbia. Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln [Between 1863 and 1866]. District of Columbia. Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln [Between 1863 and 1866].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F642a53e4-adc8-49fc-8b4e-14a9cc47a9cb_1180x842.jpeg)

The masses in the United States don’t need a violent insurrection to win governing power. While some groups like the Black Liberation Army, United Freedom Front, and Weather Underground attempted armed struggle towards the tail end of the Second Reconstruction, these efforts won no demands and alienated most of the masses. Instead mass nonviolent direct action, like strikes and civil disobedience, can be directly traced to large-scale tangible victories in the contemporary United States.

But if we are serious about shifting wealth and power to the many from the few, we must be prepared to defend against the inevitable pushback from deeply entrenched and powerful interests. In other words, power can be won with little to no use of arms and final success may still rely on winning military support.

This means we must be willing to contest within and for control over all aspects of the state apparatus, even or especially those we want to fundamentally transform—and ultimately abolish through the advancement of class struggle under socialism toward a fully classless society. In other words, we cannot replace a monolithic view of the state as “bad” with a reductive attempt to separate the state into “good” and “bad” parts. Instead, we must understand that struggle occurs within and over all components of the state apparatuses—governing, administrative, ideological, and, yes, repressive. If we are serious about changing the state, we must be willing to grapple with the contradictions that come with fighting for power within and over all of it.

In Greensboro, the ALKQN comrades understood this long before I did—running for city council and filing complaints with the Department of Justice, even as they faced targeting by local police and repression by federal agents. Like them, we must treat the state as a contradictory terrain of contestation, with all the complexity that entails.

Today, activists and organizers in Greensboro carry on the legacy of such complex struggles against, within, and for the state. This past June, the “Keep Gate City Housed” campaign won over $1.5 million in rental assistance while fundamentally shifting the narrative about the role of local government in preventing homelessness. Meanwhile, new independent political organizations like Guilford For All connect these issue fights with an electoral strategy to change who holds the power of elected office. And through affiliation with the statewide Carolina Federation, they are working to bridge these local issue and electoral campaigns with a statewide strategy to fundamentally shift governing power at the state level.

This is an uphill battle because, while the left has long been ambivalent about the state, the right has pursued a clear-eyed governing power strategy for the past 40+ years. Project 2025 is both the culmination of these power-building efforts and an attempt to use their accumulated power to replace a faltering neoliberalism with something fundamentally, frighteningly worse. Today, we face the crucial task of blocking this right-wing coup while gradually building up left alternatives.

To do so, we must understand that the state is not some static entity opposed to or outside the masses and mass struggle. Rather, the state is all around us. It is a site of mass struggle.

Zara J. is a Greensboro-born labor movement activist and Liberation Road member with an organizing background in health care and the public sector.

No comments:

Post a Comment