Archaeological dig at Tycho Brahe’s island lab reveals some of his alchemical secrets

BY JULIA ROBINSON

Pioneering preservative removal from ancient Greek ship allows accurate dating

There’s more to alchemy than its mystical nature

Colourant chemistry identifies ancient Greek workshop for Tyrian purple

While Brahe published books and articles on his astronomical work, very little is known about his alchemical studies at Uraniborg. ‘The story about Tycho is always written about the astronomy,’ Rasmussen says. ‘And the reason is that he wrote very little about his alchemy – he wanted to keep [it] secret – whereas the astronomy he published books … and that came out to the world, whereas the medicine making did not.’

After his death, Brahe’s palace and observatory on Ven was demolished and the stones reused for new, humbler buildings. However, in 1824, the remains of the observatory were unearthed, along with traces of two ovens from his laboratory. A further archaeological dig in 1988–1990, which concentrated on the garden and surrounding buildings, unearthed fragments of glass and ceramics that may have come from the laboratory.

Source: © Bildagentur/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

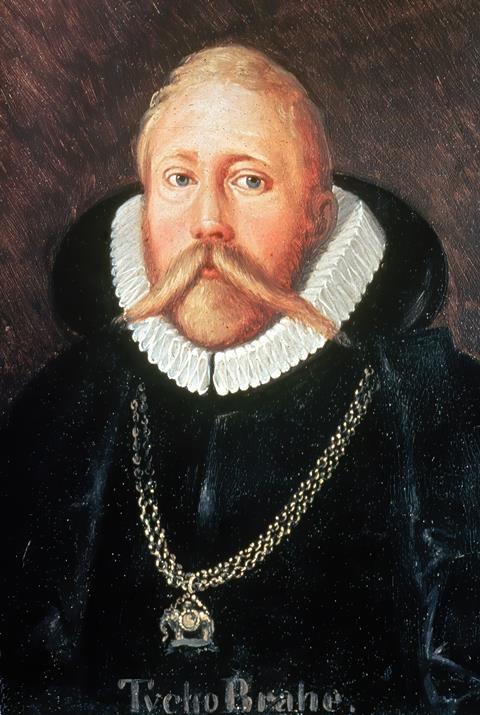

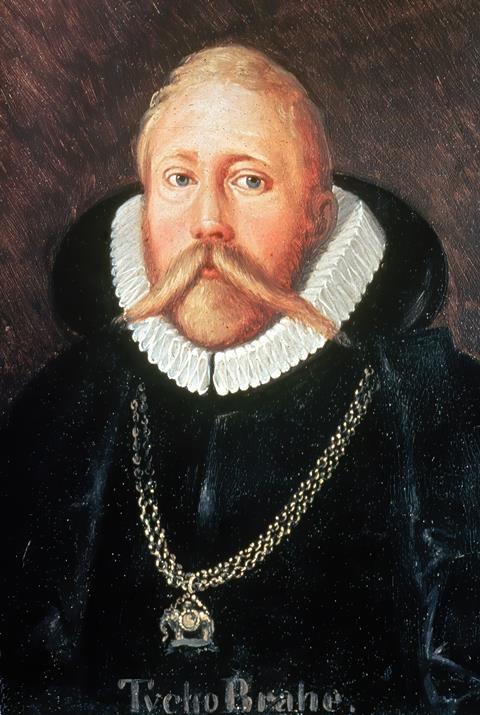

Tycho Brahe is well known as one of the last – and most influential – astronomers working before the advent of the telescope. Far less is known about his alchemical work as he kept a secret

Rasmussen and Poul Grinder-Hansen, a historian at the National Museum of Denmark, were then tasked with convincing the museum in Lund, Sweden, who had possession of hundreds of shards taken from the site, to allow them to carry out analysis on them. ‘They weren’t all too eager to do that,’ says Rasmussen. ‘[But] they gave me five shards.’

Cross sections of the shards were analysed for 31 trace elements with the aim of detecting any traces of the chemical substances on the inside or outside of the shards. ‘[We were] very lucky in the sense that [for] one shard there was nothing on either side of it,’ says Rasmussen. ‘The others, there were different elements that were clearly increased or enriched and so for the first time, we have this light cast into this laboratory.’

Source: © Kaare Lund Rasmussen and Poul Grinder‑Hansen 2024

The shards of the alchemical reaction vessels were found to contain a number of elements, including some that were virtually unknown at the time

The researchers found traces of nine chemical elements on the inner and outer surfaces of the fragments – copper, antimony, gold, mercury, nickel, zinc, tin, tungsten and lead.

The presence of copper, antimony, gold and mercury was consistent with previous research suggesting they may have been used in three of Brahe’s medical preparations. One for the prevention and treatment of an epidemic disease or other infectious contagion, a second for the treatment of epileptic diseases and a third for diseases affecting the skin and blood, such as scabies, chronic venereal diseases and elephantiasis.

‘Copper, antimony, gold and mercury were known to be used in the recipes,’ says Rasmussen. ‘But the other ones, nickel, zinc, tin, tungsten and lead, they were not mentioned anywhere. So, something else must have happened in the alchemy lab … but tungsten, that is really, really hard, because that was hardly invented [at that time].’

The researchers speculate that a tungsten-containing mineral may have been used in the laboratory because of mistaken identification or its chemical composition being unknown.

Umberto Veronesi, an archaeologist and heritage scientist based in Lisbon, Portugal, says what he found ‘particularly interesting and exciting’ about the study was that it was talking about a ‘very high profile person’ – which he says is ‘a rare occurrence’ in archaeology. ‘The beauty of archaeology is that it very often speaks to us about anonymous people – especially when it comes to this kind of scientific laboratories … we don’t really know the names and the interests of the people who are working there, they are usually quite anonymous,’ he adds. ‘That’s the big contribution of this paper, because it is like an open window, a very rare opportunity to look into what a very important person in the history of science was doing.’

Veronesi says that, having worked with similar materials before, he wasn’t surprised by the identified elements as they were consistent with someone interested in alchemy.

‘What’s important is that they found certain elements on the surfaces, especially the inner surfaces of these vessels, and that these are related to operations that could be metallurgical operations, but they equally could be medical operations,’ he says.

He adds that it would have been useful for the researchers to discuss in more detail the findings of their analysis that did not have a clear explanation.

‘They mentioned that there are some elements, like copper, like zinc, which cannot be matched to Brahe’s recipes and that’s exactly where I would have tried to dig a little more – it could tell us something, for example that Tycho Brahe was also working with copper alloys for whatever purpose, or sometimes they were trying to make alloys in order to understand how single elements and single metals work when, when treated in specific ways.’

References

K L Rasmussen and P Grinder-Hansen. Herit. Sci., 2024, DOI: 10.1186/s40494-024-01301-6

Julia Robinson

Julia joined the Chemistry World team as Science correspondent in May 2023. She previously spent eight years leading the clinical and science content at The Pharmaceutical Journal, the official journal of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, a membership body for pharmacists.View full profile

BY JULIA ROBINSON

26 JULY 2024

Analysis of glass and ceramic shards retrieved from an archaeological excavation in Sweden could reveal new insights into alchemical experiments carried out by the Renaissance astronomer, Tycho Brahe. The researchers found traces of nine chemical elements on the inner and outer surfaces of the fragments including copper, gold, zinc and tungsten.

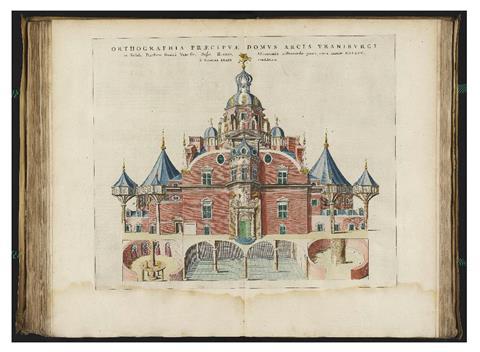

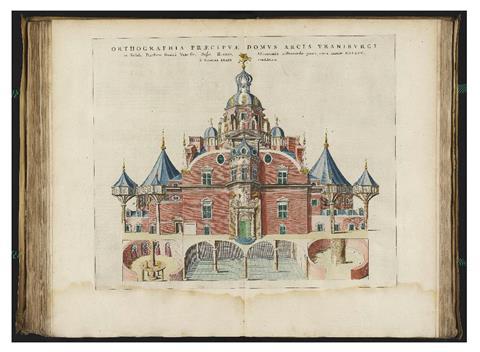

Brahe, who lived between 1546 and 1601, is well-known as an astronomer, but he also had a less well-documented interest in alchemy. In 1576, King Frederik II of Denmark offered Brahe the island of Ven as a lifelong fief, saying he wanted to support Brahe’s work. Brahe accepted and between 1576 and 1580 he erected Uraniborg, a unique combination of palace, observatory and alchemical laboratory

Uraniborg

Source: © Kaare Lund Rasmussen and Poul Grinder‑Hansen 2024

Brahe has his own observatory and lab built on an island in what is now Sweden after he found favour with the Danish king

‘It was like the Cern of the day,’ says Kaare Lund Rasmussen, professor emeritus in the department of physics, chemistry and pharmacy at the University of South Denmark, and one of the researchers leading the study.

Related stories

Analysis of glass and ceramic shards retrieved from an archaeological excavation in Sweden could reveal new insights into alchemical experiments carried out by the Renaissance astronomer, Tycho Brahe. The researchers found traces of nine chemical elements on the inner and outer surfaces of the fragments including copper, gold, zinc and tungsten.

Brahe, who lived between 1546 and 1601, is well-known as an astronomer, but he also had a less well-documented interest in alchemy. In 1576, King Frederik II of Denmark offered Brahe the island of Ven as a lifelong fief, saying he wanted to support Brahe’s work. Brahe accepted and between 1576 and 1580 he erected Uraniborg, a unique combination of palace, observatory and alchemical laboratory

Uraniborg

Source: © Kaare Lund Rasmussen and Poul Grinder‑Hansen 2024

Brahe has his own observatory and lab built on an island in what is now Sweden after he found favour with the Danish king

‘It was like the Cern of the day,’ says Kaare Lund Rasmussen, professor emeritus in the department of physics, chemistry and pharmacy at the University of South Denmark, and one of the researchers leading the study.

Related stories

Pioneering preservative removal from ancient Greek ship allows accurate dating

There’s more to alchemy than its mystical nature

Colourant chemistry identifies ancient Greek workshop for Tyrian purple

While Brahe published books and articles on his astronomical work, very little is known about his alchemical studies at Uraniborg. ‘The story about Tycho is always written about the astronomy,’ Rasmussen says. ‘And the reason is that he wrote very little about his alchemy – he wanted to keep [it] secret – whereas the astronomy he published books … and that came out to the world, whereas the medicine making did not.’

After his death, Brahe’s palace and observatory on Ven was demolished and the stones reused for new, humbler buildings. However, in 1824, the remains of the observatory were unearthed, along with traces of two ovens from his laboratory. A further archaeological dig in 1988–1990, which concentrated on the garden and surrounding buildings, unearthed fragments of glass and ceramics that may have come from the laboratory.

Source: © Bildagentur/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Tycho Brahe is well known as one of the last – and most influential – astronomers working before the advent of the telescope. Far less is known about his alchemical work as he kept a secret

Rasmussen and Poul Grinder-Hansen, a historian at the National Museum of Denmark, were then tasked with convincing the museum in Lund, Sweden, who had possession of hundreds of shards taken from the site, to allow them to carry out analysis on them. ‘They weren’t all too eager to do that,’ says Rasmussen. ‘[But] they gave me five shards.’

Cross sections of the shards were analysed for 31 trace elements with the aim of detecting any traces of the chemical substances on the inside or outside of the shards. ‘[We were] very lucky in the sense that [for] one shard there was nothing on either side of it,’ says Rasmussen. ‘The others, there were different elements that were clearly increased or enriched and so for the first time, we have this light cast into this laboratory.’

Source: © Kaare Lund Rasmussen and Poul Grinder‑Hansen 2024

The shards of the alchemical reaction vessels were found to contain a number of elements, including some that were virtually unknown at the time

The researchers found traces of nine chemical elements on the inner and outer surfaces of the fragments – copper, antimony, gold, mercury, nickel, zinc, tin, tungsten and lead.

The presence of copper, antimony, gold and mercury was consistent with previous research suggesting they may have been used in three of Brahe’s medical preparations. One for the prevention and treatment of an epidemic disease or other infectious contagion, a second for the treatment of epileptic diseases and a third for diseases affecting the skin and blood, such as scabies, chronic venereal diseases and elephantiasis.

‘Copper, antimony, gold and mercury were known to be used in the recipes,’ says Rasmussen. ‘But the other ones, nickel, zinc, tin, tungsten and lead, they were not mentioned anywhere. So, something else must have happened in the alchemy lab … but tungsten, that is really, really hard, because that was hardly invented [at that time].’

The researchers speculate that a tungsten-containing mineral may have been used in the laboratory because of mistaken identification or its chemical composition being unknown.

Umberto Veronesi, an archaeologist and heritage scientist based in Lisbon, Portugal, says what he found ‘particularly interesting and exciting’ about the study was that it was talking about a ‘very high profile person’ – which he says is ‘a rare occurrence’ in archaeology. ‘The beauty of archaeology is that it very often speaks to us about anonymous people – especially when it comes to this kind of scientific laboratories … we don’t really know the names and the interests of the people who are working there, they are usually quite anonymous,’ he adds. ‘That’s the big contribution of this paper, because it is like an open window, a very rare opportunity to look into what a very important person in the history of science was doing.’

Veronesi says that, having worked with similar materials before, he wasn’t surprised by the identified elements as they were consistent with someone interested in alchemy.

‘What’s important is that they found certain elements on the surfaces, especially the inner surfaces of these vessels, and that these are related to operations that could be metallurgical operations, but they equally could be medical operations,’ he says.

He adds that it would have been useful for the researchers to discuss in more detail the findings of their analysis that did not have a clear explanation.

‘They mentioned that there are some elements, like copper, like zinc, which cannot be matched to Brahe’s recipes and that’s exactly where I would have tried to dig a little more – it could tell us something, for example that Tycho Brahe was also working with copper alloys for whatever purpose, or sometimes they were trying to make alloys in order to understand how single elements and single metals work when, when treated in specific ways.’

References

K L Rasmussen and P Grinder-Hansen. Herit. Sci., 2024, DOI: 10.1186/s40494-024-01301-6

Julia Robinson

Julia joined the Chemistry World team as Science correspondent in May 2023. She previously spent eight years leading the clinical and science content at The Pharmaceutical Journal, the official journal of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, a membership body for pharmacists.View full profile

Date: July 25, 2024

Source: University of Southern Denmark

Summary:

Danish Tycho Brahe was most famous for his contributions to astronomy. However, he also had a well-equipped alchemical laboratory where he produced secret medicines for Europe's elite.

FULL STORY

In the Middle Ages, alchemists were notoriously secretive and didn't share their knowledge with others. Danish Tycho Brahe was no exception. Consequently, we don't know precisely what he did in the alchemical laboratory located beneath his combined residence and observatory, Uraniborg, on the now Swedish island of Ven.

Only a few of his alchemical recipes have survived, and today, there are very few remnants of his laboratory. Uraniborg was demolished after his death in 1601, and the building materials were scattered for reuse.

However, during an excavation in 1988-1990, some pottery and glass shards were found in Uraniborg's old garden. These shards were believed to originate from the basement's alchemical laboratory. Five of these shards -- four glass and one ceramic -- have now undergone chemical analyses to determine which elements the original glass and ceramic containers came into contact with.

The chemical analyses were conducted by Professor Emeritus and expert in archaeometry, Kaare Lund Rasmussen from the Department of Physics, Chemistry, and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark. Senior researcher and museum curator Poul Grinder-Hansen from the National Museum of Denmark oversaw the insertion of the analyses into historical context.

Enriched levels of trace elements were found on four of them, while one glass shard showed no specific enrichments. The study has been published in the journal Heritage Science.

"Most intriguing are the elements found in higher concentrations than expected -- indicating enrichment and providing insight into the substances used in Tycho Brahe's alchemical laboratory," said Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

The enriched elements are nickel, copper, zinc, tin, antimony, tungsten, gold, mercury, and lead, and they have been found on either the inside or outside of the shards.

Most of them are not surprising for an alchemist's laboratory. Gold and mercury were -- at least among the upper echelons of society -- commonly known and used against a wide range of diseases.

"But tungsten is very mysterious. Tungsten had not even been described at that time, so what should we infer from its presence on a shard from Tycho Brahe's alchemy workshop?," said Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Tungsten was first described and produced in pure form more than 180 years later by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Tungsten occurs naturally in certain minerals, and perhaps the element found its way to Tycho Brahe's laboratory through one of these minerals. In the laboratory, the mineral might have undergone some processing that separated the tungsten, without Tycho Brahe ever realizing it.

However, there is also another possibility that Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen emphasizes has no evidence whatsoever -- but which could be plausible.

Already in the first half of the 1500s, the German mineralogist Georgius Agricola described something strange in tin ore from Saxony, which caused problems when he tried to smelt tin. Agricola called this strange substance in the tin ore "Wolfram" (German for Wolf's froth, later renamed to tungsten in English).

"Maybe Tycho Brahe had heard about this and thus knew of tungsten's existence. But this is not something we know or can say based on the analyses I have done. It is merely a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples," said Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Tycho Brahe belonged to the branch of alchemists who, inspired by the German physician Paracelsus, tried to develop medicine for various diseases of the time: plague, syphilis, leprosy, fever, stomach aches, etc. But he distanced himself from the branch that tried to create gold from less valuable minerals and metals.

In line with the other medical alchemists of the time, he kept his recipes close to his chest and shared them only with a few selected individuals, such as his patron, Emperor Rudolph II, who allegedly received Tycho Brahe's prescriptions for plague medicine.

We know that Tycho Brahe's plague medicine was complicated to produce. It contained theriac, which was one of the standard remedies for almost everything at the time and could have up to 60 ingredients, including snake flesh and opium. It also contained copper or iron vitriol (sulphates), various oils, and herbs.

After various filtrations and distillations, the first of Brahe's three recipes against plague was obtained. This could be made even more potent by adding tinctures of, for example, coral, sapphires, hyacinths, or potable gold.

"It may seem strange that Tycho Brahe was involved in both astronomy and alchemy, but when one understands his worldview, it makes sense. He believed that there were obvious connections between the heavenly bodies, earthly substances, and the body's organs. Thus, the Sun, gold, and the heart were connected, and the same applied to the Moon, silver, and the brain; Jupiter, tin, and the liver; Venus, copper, and the kidneys; Saturn, lead, and the spleen; Mars, iron, and the gallbladder; and Mercury, mercury, and the lungs. Minerals and gemstones could also be linked to this system, so emeralds, for example, belonged to Mercury," explained Poul Grinder-Hansen.

Kaare Lund Rasmussen has previously analyzed hair and bones from Tycho Brahe and found, among other elements, gold. This could indicate that Tycho Brahe himself had taken medicine that contained potable gold.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Southern Denmark. Original written by Birgitte Svennevig. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Poul Grinder-Hansen. Chemical analysis of fragments of glass and ceramic ware from Tycho Brahe’s laboratory at Uraniborg on the island of Ven (Sweden). Heritage Science, 2024; 12 (1) DOI: 10.1186/s40494-024-01301-6

Cite This Page:MLA

APA

Chicago

University of Southern Denmark. "Chemical analyses find hidden elements from renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe's alchemy laboratory." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 25 July 2024. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/07/240725154836.htm>.

FULL STORY

In the Middle Ages, alchemists were notoriously secretive and didn't share their knowledge with others. Danish Tycho Brahe was no exception. Consequently, we don't know precisely what he did in the alchemical laboratory located beneath his combined residence and observatory, Uraniborg, on the now Swedish island of Ven.

Only a few of his alchemical recipes have survived, and today, there are very few remnants of his laboratory. Uraniborg was demolished after his death in 1601, and the building materials were scattered for reuse.

However, during an excavation in 1988-1990, some pottery and glass shards were found in Uraniborg's old garden. These shards were believed to originate from the basement's alchemical laboratory. Five of these shards -- four glass and one ceramic -- have now undergone chemical analyses to determine which elements the original glass and ceramic containers came into contact with.

The chemical analyses were conducted by Professor Emeritus and expert in archaeometry, Kaare Lund Rasmussen from the Department of Physics, Chemistry, and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark. Senior researcher and museum curator Poul Grinder-Hansen from the National Museum of Denmark oversaw the insertion of the analyses into historical context.

Enriched levels of trace elements were found on four of them, while one glass shard showed no specific enrichments. The study has been published in the journal Heritage Science.

"Most intriguing are the elements found in higher concentrations than expected -- indicating enrichment and providing insight into the substances used in Tycho Brahe's alchemical laboratory," said Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

The enriched elements are nickel, copper, zinc, tin, antimony, tungsten, gold, mercury, and lead, and they have been found on either the inside or outside of the shards.

Most of them are not surprising for an alchemist's laboratory. Gold and mercury were -- at least among the upper echelons of society -- commonly known and used against a wide range of diseases.

"But tungsten is very mysterious. Tungsten had not even been described at that time, so what should we infer from its presence on a shard from Tycho Brahe's alchemy workshop?," said Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Tungsten was first described and produced in pure form more than 180 years later by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Tungsten occurs naturally in certain minerals, and perhaps the element found its way to Tycho Brahe's laboratory through one of these minerals. In the laboratory, the mineral might have undergone some processing that separated the tungsten, without Tycho Brahe ever realizing it.

However, there is also another possibility that Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen emphasizes has no evidence whatsoever -- but which could be plausible.

Already in the first half of the 1500s, the German mineralogist Georgius Agricola described something strange in tin ore from Saxony, which caused problems when he tried to smelt tin. Agricola called this strange substance in the tin ore "Wolfram" (German for Wolf's froth, later renamed to tungsten in English).

"Maybe Tycho Brahe had heard about this and thus knew of tungsten's existence. But this is not something we know or can say based on the analyses I have done. It is merely a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples," said Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Tycho Brahe belonged to the branch of alchemists who, inspired by the German physician Paracelsus, tried to develop medicine for various diseases of the time: plague, syphilis, leprosy, fever, stomach aches, etc. But he distanced himself from the branch that tried to create gold from less valuable minerals and metals.

In line with the other medical alchemists of the time, he kept his recipes close to his chest and shared them only with a few selected individuals, such as his patron, Emperor Rudolph II, who allegedly received Tycho Brahe's prescriptions for plague medicine.

We know that Tycho Brahe's plague medicine was complicated to produce. It contained theriac, which was one of the standard remedies for almost everything at the time and could have up to 60 ingredients, including snake flesh and opium. It also contained copper or iron vitriol (sulphates), various oils, and herbs.

After various filtrations and distillations, the first of Brahe's three recipes against plague was obtained. This could be made even more potent by adding tinctures of, for example, coral, sapphires, hyacinths, or potable gold.

"It may seem strange that Tycho Brahe was involved in both astronomy and alchemy, but when one understands his worldview, it makes sense. He believed that there were obvious connections between the heavenly bodies, earthly substances, and the body's organs. Thus, the Sun, gold, and the heart were connected, and the same applied to the Moon, silver, and the brain; Jupiter, tin, and the liver; Venus, copper, and the kidneys; Saturn, lead, and the spleen; Mars, iron, and the gallbladder; and Mercury, mercury, and the lungs. Minerals and gemstones could also be linked to this system, so emeralds, for example, belonged to Mercury," explained Poul Grinder-Hansen.

Kaare Lund Rasmussen has previously analyzed hair and bones from Tycho Brahe and found, among other elements, gold. This could indicate that Tycho Brahe himself had taken medicine that contained potable gold.

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Southern Denmark. Original written by Birgitte Svennevig. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference:Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Poul Grinder-Hansen. Chemical analysis of fragments of glass and ceramic ware from Tycho Brahe’s laboratory at Uraniborg on the island of Ven (Sweden). Heritage Science, 2024; 12 (1) DOI: 10.1186/s40494-024-01301-6

Cite This Page:MLA

APA

Chicago

University of Southern Denmark. "Chemical analyses find hidden elements from renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe's alchemy laboratory." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 25 July 2024. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/07/240725154836.htm>.

No comments:

Post a Comment