The Thin Gray Line

THE JOURNALIST EYAL PRESS HAS LONG BEEN FASCINATED by the vagaries of conscience. Why do some people speak out against misconduct while others stay silent? What price does such bravery exact? What distinguishes a genuine act of moral courage from a self-interested attempt to keep one’s hands clean?

In Beautiful Souls, a tour de force of reportage from 2012, Press investigated the stories of “nonconformists” who chose to break rank when faced with grave wrongdoing. His subjects included those who helped Jewish refugees escape from Nazi Germany, rescued Croats from their Serbian tormentors, and blew the whistle on abuse at Guantánamo—often at great personal risk.

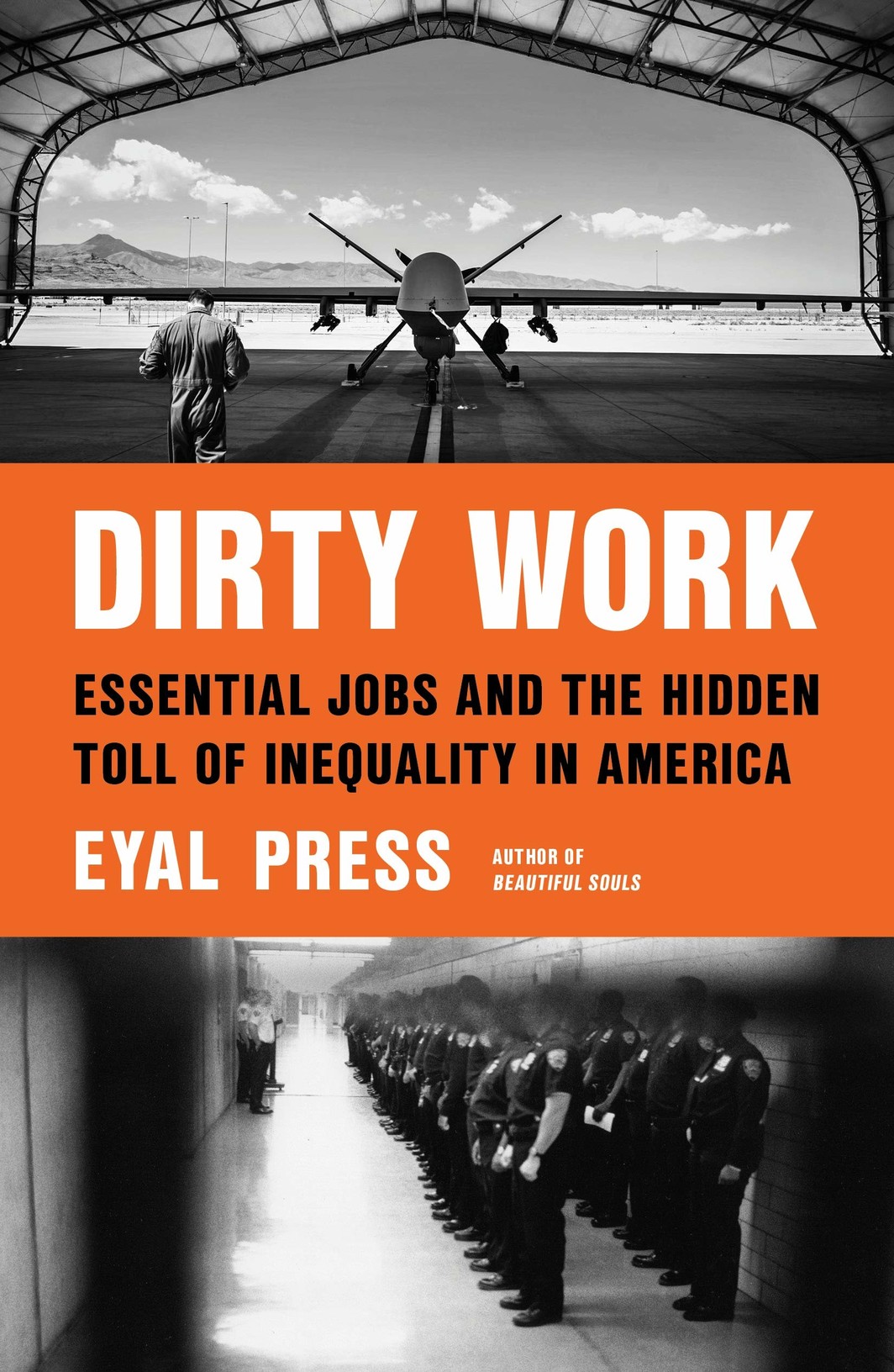

At first glance, the individuals featured in his latest book, Dirty Work, seem to belong to the opposite end of the moral spectrum. They are the prison guards and Border Patrol agents, the drone operators and slaughterhouse employees who don’t speak up about the abuses endemic to their workplaces. They hold jobs that few children want to have when they grow up and that most adults prefer not to think about. On the rare occasions when their labor receives public scrutiny, it tends to evoke discomfort, even disgust.

Through a series of intimate case studies, Press asks readers to reconsider the stark divisions that separate those who perform some of the most ethically compromising jobs in America from everyone else. “Like so much else in a society that has grown more and more unequal,” he writes, “the burden of dirtying one’s hands—and the benefit of having a clean conscience—are increasingly functions of privilege: of the capacity to distance oneself from the isolated places where dirty work is performed while leaving the sordid details to others.” This distance is not just a matter of physical barriers—the walls, fences, and concertina wire that cordon off these isolated places—but of ideological filters, which shut out “uncomfortable realizations about the things we are unwilling to countenance.”

What are we unwilling to countenance? Press, a muckracker with the sensibility of a moral philosopher, suggests that these industries depend on our complicity more than we’d like to admit. Dirty work is usually thought of as a thankless or unpleasant task, but Press uses the term to refer to something more specific: jobs that cause harm—both to others and to the workers themselves—and that come with “an unconscious mandate” from people who reap their benefits, however indirectly. His definition draws on the work of the sociologist Everett Hughes, who, in his 1962 essay “Good People and Dirty Work,” argued that the Nazis were not acting solely on behalf of the Führer: they were also “agents” of ordinary Germans who tacitly condoned a radical solution to the Jewish problem. Although conditions in Nazi Germany were a world apart from those in the United States, Hughes hoped that his essay would provoke his fellow Americans to examine the consequences of the oppressive actions performed in their name.

To be sure, Press’s subjects aren’t Nazis and they’re rarely ideologues. Many of them fall into their particular professions out of economic necessity rather than some deep-seated hatred or prejudice. Prisons, slaughterhouses, drone bases, mines, and oil rigs often function as “zoned-off worlds,” Press writes, segregated from “polite society” by class, race, and geography, and shrouded by secrecy laws. The result is a disparity that economists find hard to quantify and that therefore often goes unnamed: a profound “moral inequality” by which privileged Americans outsource compromising tasks to those with fewer choices and opportunities. One’s own sense of ethical purity stems from an ignorance of what goes on in these spaces: it’s easier for a carnivore to enjoy his burger if he doesn’t know about the suffering of either the cow or the undocumented worker who slaughtered the animal.

At a distance, it’s easy to mistake the soldier for the war machine in which he’s merely a cog. But “pinning the blame for dirty work solely on the people tasked with carrying it out,” Press argues, can obscure the power dynamics that determine who can afford to appear more virtuous. As the disillusioned journalist-narrator of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American puts it, “Perhaps to the soldier the civilian is the man who employs him to kill, who includes the guilt of murder in the pay-envelope and escapes responsibility.”

These concerns are not theoretical for Press. In the late 1990s, his father, Shalom Press, an obstetrician in Buffalo, New York, continued to provide abortions even after his colleague Dr. Barnett Slepian was assassinated by a “pro-life” terrorist. In his first book, Absolute Convictions, Press tried to understand why Shalom persisted while others in his field, cowed by a widespread campaign of intimidation, gave up. Although he clearly admires his father’s resolve—he has, after all, spent his own career chronicling the injustices brought to light by advocates and whistleblowers—his account is not without ambivalence. “The murder of Dr. Slepian touched on a division within my family about where to draw the line between high-minded principles and the bare necessity of surviving in the world,” he writes. “Now that the abstract had turned personal, and the protagonist in the story was not a human rights activist in some remote country but my own father, what I wanted was for him to relax his standards—even as I knew that he would not.”

Dirty Work marks Press’s latest journey between the kingdoms of courage and complicity. Unlike the “beautiful souls” who populate his first two books, dirty workers don’t make trouble when asked to see or do unconscionable things. That’s not necessarily because they endorse the status quo. Press’s subjects are painfully conflicted, which is part of the reason they’re willing to talk to him. Some are so troubled by their résumés that they describe the experience of opening up to a journalist as a kind of catharsis.

Take the case of Harriet Krzykowski, who in 2010 started work as a mental-health counselor at a prison in Florida. Early on, one of the incarcerated men told her that the correctional officers were starving the inmates, and not long after, she noticed other cruelties: guards taunted the men, denied them recreational privileges, and locked them in solitary confinement. When Krzykowski raised some of these issues with her superiors, security retaliated by leaving her unattended.

Two years into the job, Krzykowski learned that guards had locked a man who suffered from severe schizophrenia in a shower stall and aimed “a stream of scalding water at him.” He was not the first person to be given the “shower treatment,” only the first one to die from it. One of Krzykowski’s colleagues filed a complaint about the abuses and was later fired on the pretext of taking long lunch breaks. He was a bachelor from a wealthy family, whereas Krzykowski, a parent to young children who lacked financial security, kept quiet because she didn’t feel like she could afford to speak out.

But Krzykowski’s decision to hold on to her paycheck had its own unanticipated costs. She grew depressed and lost her appetite; her hair fell out, leaving bald patches she had to cover with scarves and wigs. Like some of the other workers Press interviews, Krzykowski was haunted by the horrifying things she witnessed but failed to prevent and was eventually diagnosed with PTSD. One former drone operator tells Press that he has a recurring dream in which he’s made to sit in a chair and rewatch the acts of violence he’s committed.

The sociologist Kelsey Kauffman has argued that the cruel logic of the prison system dehumanizes not just inmates but also the guards, whom she refers to as “the other prisoners.” Although Krzykowski felt trapped by her circumstances, she was aware that she was not an actual prisoner. The fact that she was always free to have made different choices, Press notes, heightened her sense of complicity and self-reproach. “What prompted Harriet Krzykowski to fall silent was, ultimately, that she didn’t want to antagonize security or lose her job,” he writes. “These were good reasons, but were they good enough? She wasn’t sure, which was why she kept wondering whether she was a victim of the system or a perpetrator.”

Primo Levi has written that the retrospective misgivings of oppressors are “not enough to enroll them among the victims.” But Levi also suggested that we might do well to temper our judgments of low-ranking employees in abusive systems. Press heeds Levi’s call to enter this “gray zone,” asking that we encounter his subjects with “an awareness of how susceptible we all are to collaborating with power” and “an appreciation of the circumstances that lead relatively powerless people to be pushed into such roles.”

A lesser journalist might have asked his readers to exchange their self-righteous outrage at these workers for an equally impersonal compassion. Press urges us to do something more demanding: bear witness to the complicated lives of dirty workers within the complicated systems over which they have little control.

It’s hard to read Press’s book without feeling that some of the moral opprobrium attached to dirty work should be redistributed upward—toward the CEOs and public officials who currently profit from it most. How would our society change if Wall Street bankers who sell junk loans and programmers who build surveillance software weren’t reflexively celebrated for their accomplishments—and if the rest of us began to assume our own share of the moral burden?

Some trauma experts have attempted to address the distress afflicting ex-soldiers by helping them to understand that a far broader circle of agents bears responsibility for their conduct. In Pennsylvania, one psychologist hosted weekly meetings for veterans to talk among themselves. This group therapy culminated in a public ceremony where community members linked arms around the service members who had shared their stories and delivered to them a message of reconciliation. The message, which Press suggests could be offered to a wider array of dirty workers, goes like this: “We sent you into harm’s way. We put you into situations where atrocities were possible. We share responsibility with you: for all that you have seen; for all that you have done; for all that you have failed to do.”

Ava Kofman is a reporter at ProPublica.

No comments:

Post a Comment