By Yu Ning

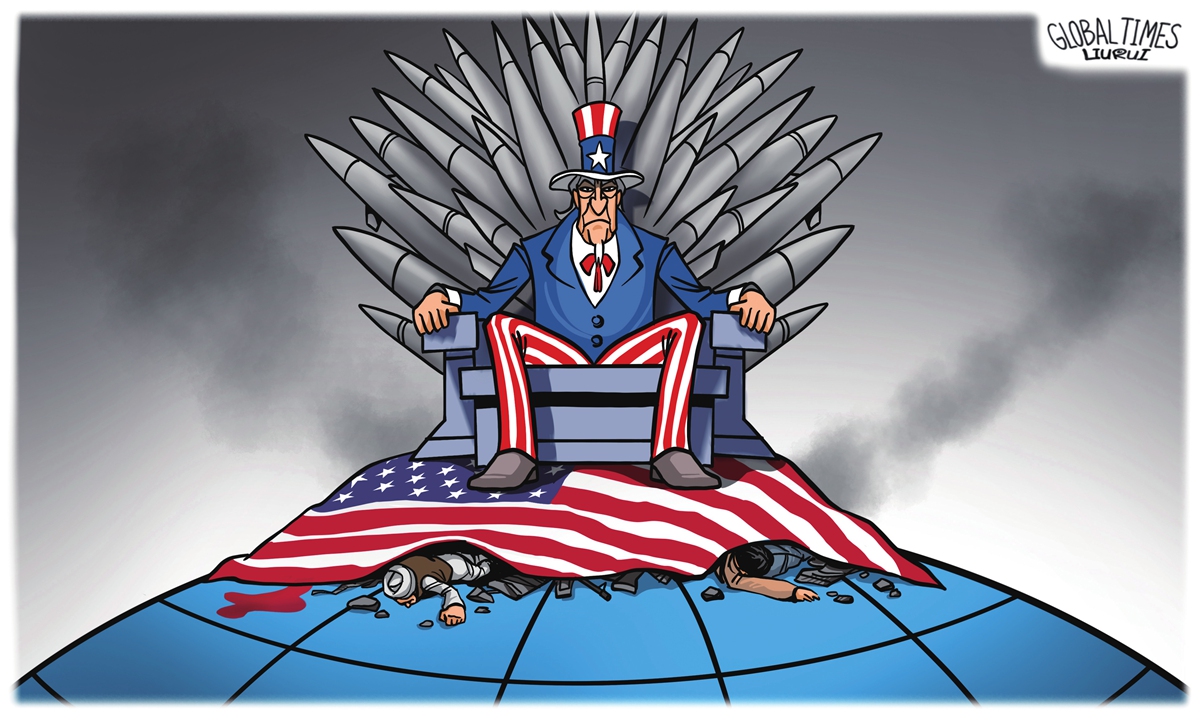

House of Hegemony Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The US, the culprit of the Ukraine crisis, has long created crises and took advantage of others' misfortune to maintain its hegemony. It hopes to use the Ukraine crisis, which has lasted for over a month, to drag Russia down, reap economic and political benefits, and prevent Europe from pursuing strategic autonomy, so as to consolidate the US hegemony. But with the discussion of the far-reaching impact of this crisis going deeper, it's increasingly believed the Russia-Ukraine conflicts actually serve as a catalyst for the burial of American hegemony.

Fareed Zakaria, a CNN host, wrote in Washington Post in March that the Russia-Ukraine war "marks the beginning of a post-America era," meaning "the Pax Americana of the past three decades is over." His argument holds water. Signs are plenty, from leaders of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who have depended on Washington for their security for decades, declining to arrange calls with US President Joe Biden, to India, a key partner that the US seeks to woo, refusing to follow the US' lead in condemning and sanctioning Russia despite repeated warnings from Washington.

Not one bloc or the other

The US is seeking to establish an anti-Russia coalition, however, it only has temporarily unified its traditional allies such as the European countries, Japan and Australia by constantly shaping the "Russia threat" and hyping the slogan of "democracy vs authoritarianism." "It does not look like the circle will grow bigger," said Oleg Ivanov, deputy head of the International and National Security Department, Diplomatic Academy, Moscow.

Over 140 countries of the more than 190 UN member states haven't participated in the sanctions against Russia. The majority of the countries in the world would like to preserve their independence in the policymaking, away from the US and its allies, and to keep away from the US' attempts to pull them into the circle, which indicates that the power and influence of the US are decreasing, Ivanov noted.

Danil Bochkov, an expert at the Russian International Affairs Council, believed that all other states outside of the US' traditional alliances are driven by a broader logic of pursuing self-interest rather than trying to present the competition with Russia as a collision of liberalism with authoritarian leadership. Under globalization, many countries have developed cooperation with Russia either in energy, trade, agriculture, or arms. "They are less willing to risk their own well-being over some murky goals of advocating for global liberalism and democracy which in some cases was also violated by the US' own actions in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria etc.," Bochkov said.

The neutrality most countries and regions maintain undoubtedly has dealt a blow to the US and other Western countries who have been accustomed to deciding what geopolitical stance other countries should take. The US can no longer corral support like it did during and after the Cold War.

A solidarity 'bubble'

When most countries are trying to push for a diplomatic solution and peace, it's the US that, for its selfish interests, constantly adds fuel to the fire for fear that the crisis will come to an end. The US expects the escalating Russia-Ukraine conflicts to make European capital flow into the US, undermine Russia, and make Europe more dependent on the US. In the short term, it seems the Ukraine crisis has united the US and Europe as never before. But is this sustainable?

Shen Yi, a professor at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs of Fudan University, believes the solidarity that the US and European allies are showing now is a bubble. "In the medium and long run, the value and significance of NATO's existence as well as US leadership will face a more substantial test," Shen noted.

"What effect have the Western 'unified' condemnation and sanctions against Russia caused? Has Russia stopped or has Ukraine been saved? Can the European countries afford keeping Russia isolated from the European economic system for a long time? Has Washington taken any substantive actions to help Europe deal with the challenges and threats brought about by the Russia-Ukraine conflicts except making money out of supplying weapons to Ukraine?" Shen asked.

The Ukraine-Russia conflict proves that simply relying on the US, an external power that maximizes its own interests by creating and maintaining certain tensions in the European continent, to protect the security of Europe is not reliable. NATO has become a political tool for the US to control Europe. "The 'brain dead' bloc, in the future, will still face deep-seated structural defects, that is, a NATO that cannot fight. What's the meaning of its existence then?" Shen asked.

Besides, the US' attempt to drag down Russia through economic sanctions won't easily succeed. Because of sanctions, Russia has been going through hard times. However, for the past eight years, Russia has adapted, to a great extent, to them - so they will not ruin the country, according to Ivanov.

As the Russia-Ukraine crisis drags on, the US will fall into a huge strategic dilemma in which it has to deal with China and Russia, two rivals it deems, simultaneously. "The US is unable to win competitions or wars on two major fronts," said Zhang Tengjun, deputy director of the Department for Asia-Pacific Studies at the China Institute of International Studies. He argued the US' current strategy will make the country face a strategic overdraft and further undermine its hegemonic status.

A post-American era

"Russian special military operation speeded up the ending of the US hegemony in the world. Thus, a new era of the multipolar world is getting closer," said Ivanov.

Fyodor Lukyanov, Director of Research at the Valdai International Discussion Club, recently published an article on RT saying that the military operations launched by Putin spelled the end of an epoch in the state of global affairs. Its impact will be felt in the coming years, and Moscow has positioned itself as an "agent of cardinal change for the whole world."

It remains to be seen what fundamental changes and far-reaching impact the Russia-Ukraine crisis will bring. But one certain thing is that with the East rising and the West falling, the existing international order has already started to change. The Russia-Ukraine conflict, in some sense, has accelerated the decline of US hegemony and the evolution of the world pattern, and has subverted the old older. The era in which the US can dictate how global affairs evolve has come to an end. A series of US-dominated institutional arrangements, including the dollar hegemony, are inevitably declining.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn

Gramsci and hegemony

The idea of a ‘third face of power’, or ‘invisible power’ has its roots partly, in Marxist thinking about the pervasive power of ideology, values and beliefs in reproducing class relations and concealing contradictions (Heywood, 1994: 100). Marx recognised that economic exploitation was not the only driver behind capitalism, and that the system was reinforced by a dominance of ruling class ideas and values – leading to Engels’s famous concern that ‘false consciousness’ would keep the working class from recognising and rejecting their oppression (Heywood, 1994: 85).

The idea of a ‘third face of power’, or ‘invisible power’ has its roots partly, in Marxist thinking about the pervasive power of ideology, values and beliefs in reproducing class relations and concealing contradictions (Heywood, 1994: 100). Marx recognised that economic exploitation was not the only driver behind capitalism, and that the system was reinforced by a dominance of ruling class ideas and values – leading to Engels’s famous concern that ‘false consciousness’ would keep the working class from recognising and rejecting their oppression (Heywood, 1994: 85).

False consciousness, in relation to invisible power, is itself a ‘theory of power’ in the Marxist tradition. It is particularly evident in the thinking of Lenin, who ‘argued that the power of ‘bourgeois ideology’ was such that, left to its own devices, the proletariat would only be able to achieve ‘trade union consciousness’, the desire to improve their material conditions but within the capitalist system’ (Heywood 1994: 85). A famous analogy is made to workers accepting crumbs that fall off the table (or indeed are handed out to keep them quiet) rather than claiming a rightful place at the table.

The Italian communist Antonio Gramsci, imprisoned for much of his life by Mussolini, took these idea further in his Prison Notebooks with his widely influential notions of ‘hegemony’ and the ‘manufacture of consent’ (Gramsci 1971). Gramsci saw the capitalist state as being made up of two overlapping spheres, a ‘political society’ (which rules through force) and a ‘civil society’ (which rules through consent). This is a different meaning of civil society from the ‘associational’ view common today, which defines civil society as a ‘sector’ of voluntary organisations and NGOs. Gramsci saw civil society as the public sphere where trade unions and political parties gained concessions from the bourgeois state, and the sphere in which ideas and beliefs were shaped, where bourgeois ‘hegemony’ was reproduced in cultural life through the media, universities and religious institutions to ‘manufacture consent’ and legitimacy (Heywood 1994: 100-101).

The political and practical implications of Gramsci’s ideas were far-reaching because he warned of the limited possibilities of direct revolutionary struggle for control of the means of production; this ‘war of attack’ could only succeed with a prior ‘war of position’ in the form of struggle over ideas and beliefs, to create a new hegemony (Gramsci 1971). This idea of a ‘counter-hegemonic’ struggle – advancing alternatives to dominant ideas of what is normal and legitimate – has had broad appeal in social and political movements. It has also contributed to the idea that ‘knowledge’ is a social construct that serves to legitimate social structures (Heywood 1994: 101).

In practical terms, Gramsci’s insights about how power is constituted in the realm of ideas and knowledge – expressed through consent rather than force – have inspired the use of explicit strategies to contest hegemonic norms of legitimacy. Gramsci’s ideas have influenced popular education practices, including the adult literacy and consciousness-raising methods of Paulo Freire in his Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), liberation theology, methods of participatory action research (PAR), and many approaches to popular media, communication and cultural action.

The idea of power as ‘hegemony’ has also influenced debates about civil society. Critics of the way civil society is narrowly conceived in liberal democratic thought – reduced to an ‘associational’ domain in contrast to the state and market – have used Gramsci’s definition to remind us that civil society can also be a public sphere of political struggle and contestation over ideas and norms. The goal of ‘civil society strengthening’ in development policy can thus be pursued either in a neo-liberal sense of building civic institutions to complement (or hold to account) states and markets, or in a Gramscian sense of building civic capacities to think differently, to challenge assumptions and norms, and to articulate new ideas and visions.

Refernces for futher reading

Freire, Paulo (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York, Herder & Herder.

Gramsci, Antonio (1971) Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci, New York, International Publishers.

Heywood, Andrew (1994) Political Ideas and Concepts: An Introduction, London, Macmillan.

No comments:

Post a Comment