UK

Tory Shadow Attorney General and peer takes job representing sanctioned Russian oligarch

DECEMBER 30, 2O25

By the Ukraine Solidarity Campaign

The Ukraine Solidarity Campaign condemns the revelation that Lord Wolfson KC, a senior Conservative peer and Shadow Attorney General, is now representing sanctioned Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich in his appeal over billions in frozen assets.

This revelation comes as Ukrainians are being killed daily by Russia’s war of aggression, with no right of appeal against bombardment, occupation, torture, or the mass abduction of children.

Yet a billionaire oligarch long linked to the Kremlin’s system of power is afforded every legal avenue to protect his fortune.

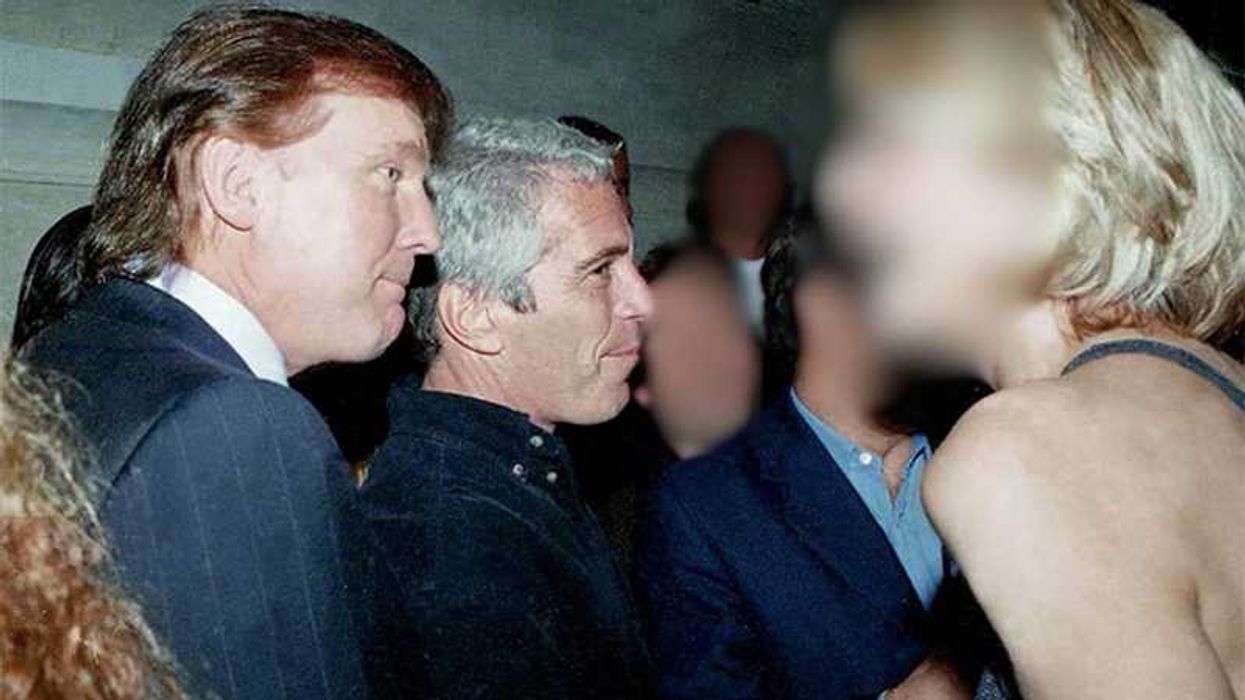

Abramovich has assembled a heavyweight multinational legal team — including Eric Herschmann, a former senior adviser to Donald Trump — to challenge the freezing of more than £5.3 billion in assets. This raises profound questions about the Conservative Party and its long‑standing entanglement with Russian wealth.

For years, the Conservatives buried the Russia Report, accepted donations linked to oligarch networks, and delayed meaningful sanctions after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014. Now, while posturing as defenders of national security, a member of their own Shadow Cabinet is representing a sanctioned oligarch in a case that directly affects Ukraine’s ability to receive urgently needed funds.

This is not an isolated incident — it reflects a wider political drift. As the Ukraine Solidarity Campaign has warned, a Trump–Putin axis is reshaping global politics, empowering authoritarian forces. The new US National Security Strategy signals a strategic shift toward accommodation with Russia and alignment with the populist far‑right in Europe.

The involvement of a former Trump adviser in Abramovich’s legal defence underscores this trend. It also raises serious questions about the Conservative Party under Kemi Badenoch’s leadership.

It is difficult to believe that a Shadow Cabinet member would take on such a case without the knowledge or approval of the party leadership. Are we seeing early indications that, ahead of any Trump–Putin attempt to impose an unjust peace on Ukraine, the Conservatives are preparing to return to ‘business as usual’ with Russia? Is this laying the groundwork for a future alignment with Nigel Farage by normalising troubling attitudes of Reform UK toward Russia?

The situation surrounding Abramovich’s assets is emblematic of a broader failure. While Ukraine continues to resist invasion under extraordinary pressure, the UK has yet to transfer frozen Russian assets to Ukraine. Meanwhile, oligarchs continue to exploit the UK legal system to delay accountability.

The Ukraine Solidarity Campaign therefore calls for:

1. Full transparency

on why a Shadow Cabinet member is representing a sanctioned oligarch.

2. Immediate action by the UK Labour government

to ensure that all frozen Russian assets — including the proceeds of the Chelsea sale — are transferred to Ukraine as a matter of urgency.

3. Implementation of the Russia Report

and a complete break with oligarchic influence. The UK must confront the networks that enabled Russian wealth to embed itself in British political and financial life.

4. Emergency legislation

to prevent the Russian state and sanctioned individuals from exploiting the UK legal system to delay accountability. The rights of victims of Russian aggression must come before the privileges of oligarchs.

The European labour movement must resist attempts to impose an unjust peace on Ukraine and must campaign for the urgent provision of increased military, economic, and humanitarian support – funded by frozen Russian assets.

The Ukraine Solidarity Campaign stands firmly with the Ukrainian people. We declare: Occupation is not peace. With or without a deal manufactured by Putin and Trump, we will continue to campaign for Russian troops out and for a free and united Ukraine — free from oligarchs and occupiers.

Labour justice minister puts pressure on Tories over shadow attorney general representing Russian oligarch

Parliamentary under-secretary of state at the Ministry of Justice, Jake Richards MP has written to Kemi Badenoch expressing concern regarding a conflict of interest over the court case of former Chelsea football club owner, Roman Abramovich.

This is due to Badenoch’s Shadow Attorney General, and senior Conservative peer, Lord Wolfson KC, being part of Mr Abramovich’s legal team in his appeal over £2.5 billion in frozen assets from his sale of Chelsea FC. The government wishes to distribute this money once claimed to support the people of Ukraine following continued Russian aggression.

In a letter to the opposition leader, posted to his X account on 29 December, Richards points out that Shadow Attorney General is a “crucial role in formulating Conservative Party policy”. He then states that as “a paid representative of Mr. Abramovich, he has a financial interest in the question of whether and when Mr Abramovich’s assets are transferred to benefit the people of Ukraine”.

READ MORE: ‘Carol of the Bells: Christmas, Ukraine’s resistance and the fight for freedom’

Richards goes on to ask four important questions of the Conservative leader in his letter.

Firstly, whether the Conservative Party agrees with the government position that the £2.5 billion should be transferred to benefit the people of Ukraine without delay?

Secondly, what role Lord Wolfson specifically played in formulating Conservative policy on this matter, did he declare an interest during any such discussions or recuse himself from such discussions?

Richards then asks specifically of Badenoch, When or if Lord Wolfson informed her about the role he was playing in this court case.

Finally he asked what her position is in regard to a Shadow Cabinet member having “a financial interest in a case that has direct bearing on the Government, and therefore Opposition, policy?”

The justice minister concludes his letter by asking that if Wolfson is to continue to represent Mr Abramovich, he should not do so whilst serving in the Shadow Cabinet, leaving both the shadow minister and the leader of the opposition with a decision to make.

The letter was posted to his Richards’ X account and he also reposted from @LabourPress who call this matter “indefensible” stating, “Lord Wolfson can either be Shadow Attorney General or Roman Abramovich’s lawyer. He can’t be both.”

How Badenoch and the Conservative Party choose to respond remains to be seen.

.JPG)