(RNS) — The renowned New Testament scholar and former dean of Duke Divinity School described his most recent book as an act of repentance for the way his work had been used to harm LGBTQ people and to divide Christians.

Richard Hays. (Photo courtesy of Duke)

Bob Smietana

January 4, 2025

(RNS) — Richard Hays, a renowned New Testament scholar and former dean of Duke Divinity School known for his influential books on Christian ethics and his change of mind about same-sex marriage, died Friday (Jan. 3) at his home in Nashville, Tennessee, from pancreatic cancer. Hays was 76.

“He was surrounded by his books, overseen by photos of his parents and wide family, and with Christmas music from Kings College Cambridge playing softly in the background,” his wife, Judy, wrote on CaringBridge.org, in announcing his death.

A former English teacher and pastor, Hays was a graduate of Yale University and Yale Divinity School and earned his doctorate from Emory University in 1981. He then returned to teach New Testament at Yale from 1981 to 1991 and then at Duke Divinity School until his retirement in 2018.

For much of his career, he was perhaps best known for his 1996 book, “The Moral Vision of the New Testament,” in which he argued that same-sex relationships were “one among many tragic signs that we are a broken people, alienated from God’s loving purpose.” His well-respected scholarly work was cited by Christian leaders who viewed same-sex relationships as sinful and who opposed LGBTQ affirmation in churches.

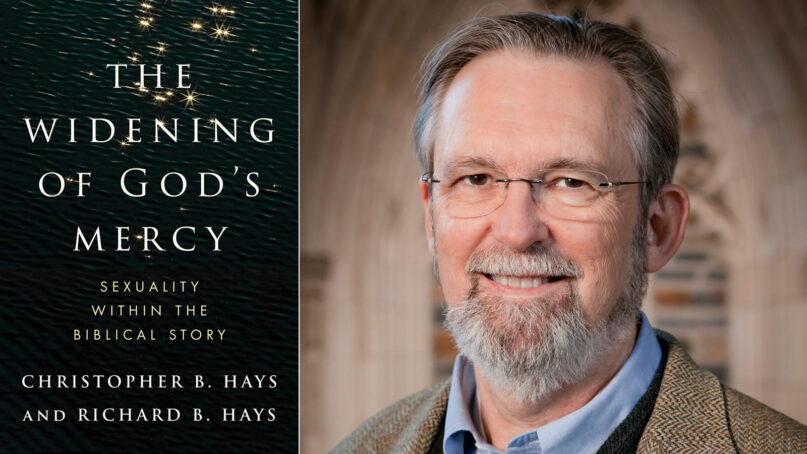

This past year, Hays publicly changed his mind — in what he described as an act of repentance for the way his work had been used to harm LGBTQ people and to divide Christians — in a new book, “The Widening of God’s Mercy: Sexuality Within the Biblical Story,” co-authored with his son, Christopher Hays, an old Testament scholar.

RELATED: Richard Hays and the lost art of repentance

In the book’s introduction, Richard Hays recounts how his brother initially balked at attending their mother’s funeral, because her church, where the service would be held, affirmed same-sex relationships. That prompted him to reflect on the place of LGBTQ Christians in the church.

“The Widening of God’s Mercy: Sexuality Within the Biblical Story” and co-author Richard Hays. (Photo courtesy of Duke)

In the years since 1996, Hays had been rethinking his interpretation of the biblical texts barring same-sex relations because of his experience of teaching gay students in seminary and seeing the faithful service of gay Christians in local churches, he told Pete Wehner in a New York Times interview last year.

That included Hays’ own congregation, where “I saw church members who were not theological students or anything like that but who were exercising roles of gracious and meaningful leadership,” he told Wehner.

Hays was also concerned about what he called “smug hostility” among more conservative Christians toward LGBTQ church members, something he felt in part responsible for and something he hoped to make amends for.

“The present book is, for me, an effort to offer contrition and to set the record straight on where I now stand. … I am deeply sorry,” he told RNS in 2024. “The present book can’t undo past damage, but I pray that it may be of some help.”

The new book, which argues God has changed his mind about same-sex relationships and other boundaries that keep some people outside his grace, was seen as a betrayal by conservatives who agreed with his former book, with some going as far as to call it heretical. But Hays told National Public Radio that he was at peace with his change of mind, though he knew it would cause controversy.

“So there’s a sense in which I’m eating some of my own words, and I’m concerned that it will perhaps burn some bridges and break some relationships that I’ve cherished,” he told NPR. “But as I age, I wanted my final word on the subject to be out there. And so there it is.”

Hays was initially diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in July 2015 and at the time had been given a dire prognosis, with his doctor telling him he might be dead by Christmas of that year. But surgery and chemotherapy put his cancer into remission until 2022, when it returned. Despite more treatment, the cancer had spread to his lungs by the summer of 2023 and eventually he went into hospice care.

This past fall, he wrote a health update asking for prayer, knowing the cancer would likely soon take his life, and sharing how his faith was shaping his approach to life in his dying days.

“Over these past nine years, Judy and I have become practiced in looking death in the face,” he wrote. “We continue to trust that we are in the hands of a merciful God who loves us. And we continue to anticipate the power of the resurrection. It’s a hard thing to know with some certainty that I will not be here to watch my grandchildren grow up. But as in years before, we remain grateful for each new day in which we can join the Psalmist in proclaiming: ‘This is the day that the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it.’”

Hays is survived by his wife, Judy, and children Christopher and Sarah.

According to an update posted on CaringBridge, Hays will be interred in Oklahoma City, with services to follow at a later date at McKendree United Methodist Church in Nashville and at Duke.

Opinion

In Richard Hays, a rare combination of confidence and contrition

(RNS) — All of this full and good life was funded by an unapologetic conviction about the mercy of God at work in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Richard Hays. (Photo courtesy of Duke)

Beverly Gaventa

January 5, 2025

(RNS) — Professor Richard Hays, a Scripture scholar of vast influence, both through his scholarship and through his leadership in theological education, died on Friday, Jan. 3, the result of a long journey with pancreatic cancer and the end of a remarkable life.

When New Testament specialists refer to the scholarship of Richard Hays, we are apt to resort to shorthand expressions. “Narrative substructure,” “subjective genitive” and “echoes of Scripture” are three that come immediately to mind, and rightly so, as Richard’s publications on these topics set waves of research in motion. But Richard was more than a set of propositions in need of defense. His work was enriching because it was itself enriched by the English language he so cherished. His early devotion to poetry paid off, not because he raided Harold Bloom, but because he read Milton and Yeats and Arnold and Eliot. Every word mattered, whether it was an ancient word or a modern one, and that made Richard’s own words more powerful.

Richard pursued his work with a confidence that manifested itself in his early willingness to take on scholarly positions that were generally thought to be “settled.” We were at a Columbia Seminar dinner together sometime in the early 1980s — well before even his dissertation had been published — when he instigated a heated discussion about the “faith of Christ” among senior scholars at the table. Neither on that evening nor later did I sense Richard was being provocative just to be provocative; he did it out of genuine conviction for the topic at hand.

That confidence was coupled, even mellowed, by a well-honed willingness to hear and respond to criticism. When “The Moral Vision of the New Testament” was still in draft form, he hosted a small conference at Duke, inviting numerous colleagues to interact with its chapters. Richard gracefully endured several days of critique — some of it quite forceful — in the interest of improving his work. Some years later, after the publication of “Seeking the Identity of Jesus” — a book we edited together through the auspices of the Center of Theological Inquiry in Princeton — Tom Wright issued a stinging critique of the volume in a book review panel at a national meeting. True to his own character, although Richard was dismayed by the critique and disagreed with it, he maintained his respect and deep affection for Tom.

I experienced that commitment to friendship myself, as Richard and I navigated our own disagreements. Conversations around several topics, most notably human sexuality and abortion, found us on opposite sides, and awkwardly so at times. Yet I never considered that Richard might see these as friendship-terminating moments, and I trust he never experienced anxiety over that possibility. To be sure, we both lived with privileges that allowed us to maintain the friendship, but I think something other than privilege was at work. We had been given to each other as friends, and that gift was not to be questioned or cast aside.

In the final years of his life, Richard demonstrated in a public way that confidence about one’s work needs to be coupled with the ability to change one’s mind. When he and his son, Christopher B. Hays, published “The Widening of God’s Mercy” in 2024, Richard made public what many of us knew, namely, that he had changed his mind about the interpretation of Scripture and the question of same-sex relations. Richard was aware that his earlier position, argued in “Moral Vision,” had contributed to a hardening of the categories in some church circles, and he wanted very much to give public voice both to his change of mind and to his change of heart. It is a testimony to the divine mercy of the title of that book that it was published before Richard’s death.

RELATED: Richard Hays and the lost art of repentance

The intensity that characterized Richard’s work also characterized his support of students and friends. I can recall warm introductions to Love Sechrest, Ross Wagner and Brittany Wilson, among others — students Richard wanted to bring to the attention of his own scholarly friends — friendships he hoped to generate. And I am deeply grateful for his support in times of personal crisis, to say nothing of his encouragement of my own work. During one season when both of us were in Princeton, we met several times to work through a translation of Romans. Those conversations were rich and precious, even if we did try the patience of restaurant staff who needed us to move along.

Such intensity can come at the expense of family, and Richard was painfully aware that his own family sometimes paid a steep price for his vocation. He acknowledged that price explicitly in the preface to “Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels,” which is dedicated to his wife, Judy. In many conversations over the years, however, he always reported on Judy’s work with pride and genuine interest. And no conversation was complete until we had shared reports on our children and, with time, the grandchildren. Unquestionably, Richard loved and was loved in a way that sustained him and allowed all of them to flourish.

All of this full and good life was funded by an unapologetic conviction about the mercy of God at work in the gospel of Jesus Christ. While Richard held that there was value in historical critical investigation, it was not for him a mere parlor game but part and parcel of a quest to understand what God has done in the world and to find our place in that story. It surprised me not at all to find that his own last message on his CaringBridge site came from Romans 14:

Richard knew who his Lord was, and he knew what his own vocation was. The church and the academy have been the beneficiaries of that life.

(Beverly Roberts Gaventa is Helen H.P. Manson Professor of New Testament Emerita at Princeton Theological Seminary and Distinguished Professor of New Testament (retired) at Baylor University. Her most recent book is “Romans: A Commentary” (WJK, 2024). The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

In Richard Hays, a rare combination of confidence and contrition

(RNS) — All of this full and good life was funded by an unapologetic conviction about the mercy of God at work in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Richard Hays. (Photo courtesy of Duke)

Beverly Gaventa

January 5, 2025

(RNS) — Professor Richard Hays, a Scripture scholar of vast influence, both through his scholarship and through his leadership in theological education, died on Friday, Jan. 3, the result of a long journey with pancreatic cancer and the end of a remarkable life.

When New Testament specialists refer to the scholarship of Richard Hays, we are apt to resort to shorthand expressions. “Narrative substructure,” “subjective genitive” and “echoes of Scripture” are three that come immediately to mind, and rightly so, as Richard’s publications on these topics set waves of research in motion. But Richard was more than a set of propositions in need of defense. His work was enriching because it was itself enriched by the English language he so cherished. His early devotion to poetry paid off, not because he raided Harold Bloom, but because he read Milton and Yeats and Arnold and Eliot. Every word mattered, whether it was an ancient word or a modern one, and that made Richard’s own words more powerful.

Richard pursued his work with a confidence that manifested itself in his early willingness to take on scholarly positions that were generally thought to be “settled.” We were at a Columbia Seminar dinner together sometime in the early 1980s — well before even his dissertation had been published — when he instigated a heated discussion about the “faith of Christ” among senior scholars at the table. Neither on that evening nor later did I sense Richard was being provocative just to be provocative; he did it out of genuine conviction for the topic at hand.

That confidence was coupled, even mellowed, by a well-honed willingness to hear and respond to criticism. When “The Moral Vision of the New Testament” was still in draft form, he hosted a small conference at Duke, inviting numerous colleagues to interact with its chapters. Richard gracefully endured several days of critique — some of it quite forceful — in the interest of improving his work. Some years later, after the publication of “Seeking the Identity of Jesus” — a book we edited together through the auspices of the Center of Theological Inquiry in Princeton — Tom Wright issued a stinging critique of the volume in a book review panel at a national meeting. True to his own character, although Richard was dismayed by the critique and disagreed with it, he maintained his respect and deep affection for Tom.

I experienced that commitment to friendship myself, as Richard and I navigated our own disagreements. Conversations around several topics, most notably human sexuality and abortion, found us on opposite sides, and awkwardly so at times. Yet I never considered that Richard might see these as friendship-terminating moments, and I trust he never experienced anxiety over that possibility. To be sure, we both lived with privileges that allowed us to maintain the friendship, but I think something other than privilege was at work. We had been given to each other as friends, and that gift was not to be questioned or cast aside.

In the final years of his life, Richard demonstrated in a public way that confidence about one’s work needs to be coupled with the ability to change one’s mind. When he and his son, Christopher B. Hays, published “The Widening of God’s Mercy” in 2024, Richard made public what many of us knew, namely, that he had changed his mind about the interpretation of Scripture and the question of same-sex relations. Richard was aware that his earlier position, argued in “Moral Vision,” had contributed to a hardening of the categories in some church circles, and he wanted very much to give public voice both to his change of mind and to his change of heart. It is a testimony to the divine mercy of the title of that book that it was published before Richard’s death.

RELATED: Richard Hays and the lost art of repentance

The intensity that characterized Richard’s work also characterized his support of students and friends. I can recall warm introductions to Love Sechrest, Ross Wagner and Brittany Wilson, among others — students Richard wanted to bring to the attention of his own scholarly friends — friendships he hoped to generate. And I am deeply grateful for his support in times of personal crisis, to say nothing of his encouragement of my own work. During one season when both of us were in Princeton, we met several times to work through a translation of Romans. Those conversations were rich and precious, even if we did try the patience of restaurant staff who needed us to move along.

Such intensity can come at the expense of family, and Richard was painfully aware that his own family sometimes paid a steep price for his vocation. He acknowledged that price explicitly in the preface to “Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels,” which is dedicated to his wife, Judy. In many conversations over the years, however, he always reported on Judy’s work with pride and genuine interest. And no conversation was complete until we had shared reports on our children and, with time, the grandchildren. Unquestionably, Richard loved and was loved in a way that sustained him and allowed all of them to flourish.

All of this full and good life was funded by an unapologetic conviction about the mercy of God at work in the gospel of Jesus Christ. While Richard held that there was value in historical critical investigation, it was not for him a mere parlor game but part and parcel of a quest to understand what God has done in the world and to find our place in that story. It surprised me not at all to find that his own last message on his CaringBridge site came from Romans 14:

We do not live to ourselves, and we do not die to ourselves.If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord;So then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s.

Richard knew who his Lord was, and he knew what his own vocation was. The church and the academy have been the beneficiaries of that life.

(Beverly Roberts Gaventa is Helen H.P. Manson Professor of New Testament Emerita at Princeton Theological Seminary and Distinguished Professor of New Testament (retired) at Baylor University. Her most recent book is “Romans: A Commentary” (WJK, 2024). The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

No comments:

Post a Comment