Where the Pandemic Leaves the Climate Movement

Anneleen Kenis

Manuel Arias-Maldonado

Paolo Cossarini

Susan Baker

GREEN TRANSITION

21 AUGUST 2020

As the entire globe is in the middle of an unprecedented pandemic, with great economic, social, and environmental consequences, it is worth recalling mass mobilisations like Extinction Rebellion and Fridays For Future which took the global scene in spring 2019. A year on, it is time to examine their claims and impact on public awareness of the climate emergency as well as current political discourse and policymaking. Paolo Cossarini spoke with three scholars from different European countries who highlight fundamental themes these movements helped bring to the fore. What emerges is a nuanced theoretical and practical debate about citizens’ mobilisation, green transition, and the prospects of climate action.

Paolo Cossarini: A year ago, Extinction Rebellion (XR) shut down London’s streets, as did Fridays for Future (FFF) in cities across the globe, making headlines worldwide. In 2020, streets have been shut down once more to prevent a health crisis. One year on, how have these movements shifted the debate on climate change?

Manuel Arias-Maldonado: In my view, these movements have not been as important as the increase in extreme weather events that have shaken public opinions in the last years, creating a feeling of urgency the movements themselves can profit from. It is the sense that something is palpably changing that propels public awareness. Protest movements are relevant, among young people especially, but they would be helpless in the absence of such material conditions which are, admittedly, as much objective as they are mediated by mass media.

Susan Baker: The climate movement is positive. However, the emphasis on “listen to science” is potentially problematic in that it fails to grasp that science does not reveal the truth but aspects of what is known. Climate science is narrow: it defines the issue in the language and framework of the natural sciences, ignoring the main causes of and solutions to climate change which lie in the social world in general, and in our economic model in particular. Neither of these groups have a critical grasp of the fundamental causes of climate change.

the emphasis on “listen to science” is potentially problematic in that it fails to grasp that science does not reveal the truth but aspects of what is known.

While XR and FFF have promoted public awareness, both are very moderate voices and have, consequently, shrunk the space for radical ones. On climate action, their focus on transition favours technocratic responses as opposed to radical transformation. It is therefore likely that transition management (transition to low carbon futures that allows for business as usual), as opposed to transformation, will take centre stage in climate action.

Where do you think the Covid-19 pandemic leaves the climate movement?

Anneleen Kenis: XR and FFF are remarkably absent in the current crisis though they seem to be slowly becoming more active again. The coronavirus pandemic might give the feeling that there are more important things to focus on now, but nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, the Covid-19 crisis is instructive because it has unveiled how societies deal with emergencies, the place of science in the public debate, and human-nature relationships. Furthermore, the pandemic could nudge us in the direction of a radically different, much more sustainable society, but it could also lead us to a society characterised by authoritarian control, moralisation, and securitisation.

the Covid-19 crisis is instructive because it has unveiled how societies deal with emergencies, the place of science in the public debate, and human-nature relationships.

There is no neutral answer to the coronavirus crisis, just as there is no neutral answer to climate change. What’s more, the pandemic continues to raise crucial questions: who will foot the bill? Will large economic sectors like the airline industry be saved with taxpayers’ money? What conditions will these sectors have to meet? Will generating even more profit and growth be an indispensable mission? Will the coronavirus-induced economic crisis be used to demarcate certain sectors as crucial and others as not? Will we invest in healthcare and public schooling instead of (polluting) companies?

Manuel Arias-Maldonado: Nobody knows. There are reasons to think that climate action may be encouraged after the pandemic – or even during the pandemic if it doesn’t end soon – as well as to fear that the return to normality will prioritise economic growth over sustainability concerns or climate mitigation. Mobilising the public all depends on how people will feel after this is over.

In the meantime, it may be possible to seize temporary feelings to rally support for climate-friendly coronavirus response legislation as a way to ensure a cleaner exit from the crisis. The climate movement can play a role in this mobilisation process by framing the pandemic as the first true catastrophe of the Anthropocene. However, this card should not be overplayed since the link is not always clear. Alternatively, the pandemic can be portrayed as an expression of careless modernity, one that does not take into account, for example, food security. This depiction brings globalisation and the call to make it more sustainable centre stage.

Susan Baker: It is clear that government-imposed restrictions on social gatherings have impacted the activities of climate activist groups. So far, FFF has stopped their street presence and XR have ceased their highly visible forms of public protest. They nevertheless continued their activism online throughout the lockdown. These groups relied heavily on civil protest to raise public awareness, believing that this would force governments and other key stakeholders to act. It is harder to credit posting a selfie with a placard during lockdown with the same impact. Digital activism can be easily dismissed as an individualised activity while the marches that took place in the streets, often noisily, can hardly be written off.

In the public arena, there is a danger that the voices that speak for nature and that seek climate action will once again become marginalised. There continues to be a great deal of attention paid to how to manage the pandemic, as we would expect. At the same time, there is a lack of discussion on the underlying causes – which lie in the destruction of ecosystems for trafficking of species – and how the problem will be addressed at source.

Despite these challenges, the quietening of our streets and the cleaning of our air during lockdowns have allowed people to see and hear nature again. Here lies the hope that people can carry this experience forward to form a new political consciousness about the environmentally destructive nature of our economic activities and the possibility of an alternative future.

Do you think an overhaul of the relationship between our economic systems and the environment is possible in the current moment? How can we make a green transition attractive to the economic and political forces desperately trying to stay afloat and return to business as usual?

Anneleen Kenis: I would start by questioning this question: do we really have to make sustainability attractive to economic forces and industry? Or should we rather put economic forces and industry under pressure to change? The environmental movement has bought too much into the idea that we can get everyone on board if we come up with an “attractive” vision. It reinforces the idea that we can save the world with technofixes, that nothing really has to change, and that air transport does not have to be fundamentally questioned after all. We need to apply pressure now that it is possible. Or refuse to rescue them: we should simply say “no” and take proper measures to ensure that future companies do not have all the tax and other advantages that the aviation sector has.

While a certain level of “greening” the capitalist economy is possible (capitalists can make money selling solar panels just as they make money selling coal or oil), there is a fundamental clash. This clash has several aspects and dimensions, but the huge cleavage is between pursuing economic growth and reducing pressure on the ecosystems we are fundamentally a part of.

Manuel Arias-Maldonado: Before the pandemic, I would have answered that winning the support of economic and political forces is possible by making a green transition both unnegotiable and profitable. The transition could be framed as something unavoidable but a possible source of innovation and value.

Now, the world has stopped for some time and I think that public perception will be impacted for two reasons. Firstly, the dangers associated with the Anthropocene have been highlighted. Secondly, lockdowns have shown that life can be better: cleaner, healthier, slower.

There is no one way to stop climate change but several.

Additionally, the economic situation may provide governments with the opportunity to foster new energy technologies, thus giving some unexpected momentum to the green transition. Emmanuel Macron has hinted that polluted air will not be tolerated anymore. Well, this is the time to start.

There is no one way to stop climate change but several. Some are more capitalist-friendly – by way of technological innovation and productivity and efficiency gains – while others are more community-based and depend on reducing the size of the economy.

Susan Baker: At present, there is a dynamic interplay between pressure for change and the return to old ways. Climate change has shown that it is no longer possible to see our economic activity in isolation from its ecological and social consequences. This realisation calls upon us to question equating human progress with the domination of nature.

Economic actors need to take responsibility for their actions. It is not a question of “making it attractive to them”. Attractive, in the traditional economic sense, means that the activity can be the source of profits. This model that allows some in society to generate excessive wealth at the cost of others, including nature, needs to change. We must change what is produced, how it is produced, evaluate who benefits, and at what cost. It would be a moral hazard to make a green transition attractive when what we need is a green transformation of society.

We must change what is produced, how it is produced, evaluate who benefits, and at what cost.

Do you think that there’s the potential for a paradigm shift away from an economy based on growth? What about the balance between collective and individual action?

Anneleen Kenis: There are many consumer goods with huge ecological costs for which it cannot be sincerely argued that they are essential to lead a healthy and comfortable life. The global fashion industry contributes more to climate change than shipping and aviation together. This is no surprise considering that, in the UK for instance, 300 000 items of clothes are thrown away every year [read more on the impacts of fast fashion]. A first step to promoting degrowth is banning advertisement. People are told on an almost continuous basis that they need all this stuff.

Everyone who has the capacity to make personal changes should consider doing so. However, as Giorgos Kallis argues, it is much easier, much more motivating, and more impactful to do so collectively [read about Kallis’ insights on limits and autonomy]. I decided 10 years ago not to fly anymore, but what difference does it make? If we were to make a similar commitment collectively, the impact could be huge.

Manuel Arias-Maldonado: There is no consensus on degrowth as the way to go in terms of building a particular kind of society. It would be an accepted model if it was the only way to prevent planetary collapse – which it is not. There are alternative ways to promote decarbonisation and sustainability and governments should focus on those. What’s more, economic growth still matters as a way of producing welfare and wellbeing. Degrowth must, therefore, be defended as a morally valuable choice. If it were to persuade a majority, it would be the blueprint for a new way of living.

As I see it, relying on such collective sacrifice is utterly unrealistic. Nevertheless, people should be made aware of the fact that human habitation of the planet depends on the planet’s conditions, which in turn depend on how people behave. This understanding could bring our planetary impact into focus and potentially lead to better policy and technological innovation.

Susan Baker: The growth-oriented model of development pursued by Western industrial societies cannot be carried into the future, either in its present forms or at its present pace, as evidenced by climate change. We cannot have continuous growth in a system characterised by resource limits and planetary boundaries. Climate change has been caused by a growth-orientated model, achieved through ever-increasing levels of consumption. This artificially stimulated consumption brings untold wealth for the few and impoverishment for the many. Many now also reject the idea that consumption is the most important contributor to human welfare. This new value is not compatible with capitalism. Degrowth is no longer a radical alternative, but a necessity.

We cannot have continuous growth in a system characterised by resource limits and planetary boundaries.

A healthy society and the wellbeing of its members rests on acts of services and the sense of community rather than on consumption. Adopting this model requires changing our values so that one’s social standing is not determined by what they consume and put on display, but by how they engage in society to protect the interests of others, including those of other life forms, in ways that promote justice and equity.

While personal change is important, structural factors can make them unsustainable. To move to a new model of economy and society, everyday actions would need to be accompanied by structural changes. As we rethink, for example, the way we travel, our food and energy consumption, the structures underlying these – trade, financial, food systems and our economic system overall – must be transformed as well.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

A God of Time and Space: New Perspectives

on Bob Dylan and Religion

Volume editor: Robert W. Kvalvaag, Geir Winje

Chapter authors: Reidar Aasgaard, Erling Aadland, Pål Ketil Botvar, Gisle Selnes, Anders Thyrring Andersen, Petter Fiskum Myhr

Synopsis

This book is a collection of essays on Bob Dylan and religion. The eight scientific essays present new perspectives on the subject, aiming to elucidate the role played by religion in Bob Dylan’s artistic output and in the reception history of some of his songs.

Few would dispute the fact that religion or religious traditions and the use of religious imagery have always played an important role in Dylan’s artistry. Scholars agree that the term “religion” is ambiguous and not easy to define, and a critical attitude to the whole concept of religion is traceable in Dylan’s lyrics. However, in several interviews Dylan has also revealed a positive attitude towards religion, and explained that the source of his religiosity is in the music and in old, traditional songs.

DOWNLOAD FULL PDF

on Bob Dylan and Religion

Volume editor: Robert W. Kvalvaag, Geir Winje

Chapter authors: Reidar Aasgaard, Erling Aadland, Pål Ketil Botvar, Gisle Selnes, Anders Thyrring Andersen, Petter Fiskum Myhr

Synopsis

This book is a collection of essays on Bob Dylan and religion. The eight scientific essays present new perspectives on the subject, aiming to elucidate the role played by religion in Bob Dylan’s artistic output and in the reception history of some of his songs.

Few would dispute the fact that religion or religious traditions and the use of religious imagery have always played an important role in Dylan’s artistry. Scholars agree that the term “religion” is ambiguous and not easy to define, and a critical attitude to the whole concept of religion is traceable in Dylan’s lyrics. However, in several interviews Dylan has also revealed a positive attitude towards religion, and explained that the source of his religiosity is in the music and in old, traditional songs.

DOWNLOAD FULL PDF

https://press.nordicopenaccess.no/index.php/noasp/catalog/book/74

CHAPTERS (PDF TO DOWNLOAD)

Introduction: Bob Dylan and Religion: New Perspectives from the North Country

Robert W. Kvalvaag, Geir Winje

Chapter 1: "Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)": A Window into Bob Dylan's Existential and Religious World

Reidar Aasgaard

Chapter 2: "The Titanic sails at dawn": Bob Dylan, "Tempest", and the Apocalyptic Imagination

Robert W. Kvalvaag

Chapter 3: Against Liberals: Multi-layered and Multi-directed Invocation in Bob Dylan's Christian Songs

Erling Aadland

Chapter 4: When the Wind is the Answer. The Use of Bob Dylan Songs in Worship Services in Protestant Churches

Pål Ketil Botvar

Chapter 5: The Visual Dylan: Religious Art, Social Semiotics and Album Covers

Geir Winje

Chapter 6: Bob Dylan's Conversions: The "Gospel Years" as Symptom and Transition

Gisle Selnes

Chapter 7: Hard Rain: The End of Times and Christian Modernism in the work of Bob Dylan

Anders Thyrring Andersen

Chapter 8: Bob Dylan's Ten Commandments – a Method for Personal Transformation

Petter Fiskum Myhr

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

Robert W. Kvalvaag

Robert W. Kvalvaag is professor at Oslo Metropolitan University, where he teaches religious studies at the Faculty of Teacher Education and International Studies. He has published three books (in Norwegian): From Moses to Marley, The divine I, and The Eleventh Commandment: Religion and Rock and Roll. Together with Pål Ketil Botvar and Reidar Aasgaard he also edited and contributed to Bob Dylan: The Man, the Myth and the Music. The writer of numerous articles on religion and popular culture published in anthologies and journals, his output has included works on Dylan’s use of the Bible in the early songs, and a study of the influence of Hal Lindsey on Dylan’s oeuvre in the so-called Gospel period.

Geir Winje

Geir Winje is professor in the science of religion. He works at the University of South-Eastern Norway, mostly with teacher education on different levels. He does research and publishes on three main fields: didactics of religion, art and religion, and modernity and religion. Some central books: Felles, grunnleggende verdier? Menneskerettigheter og religionspluralisme i skolen (Common, basic values? Human Rights and religious pluralism in school, 2017), Guddommelig skjønnhet. Kunst i religionene (Divine Beauty. Art in the Religions, 2nd ed. 2012), Hekser og healere. Religion og spiritualitet i det moderne (Whitches and Healers. Religion and Spirituality in Modernity, 2007).

Reidar Aasgaard

Reidar Aasgaard is Professor of Intellectual History at the Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas (IFIKK), University of Oslo. He has published books and articles in English and Norwegian on the history of childhood, the New Testament, Late Antiquity, and early Christian apocrypha. He has worked as a Bible translator and translated classical texts from Greek and Latin into Norwegian. Aasgaard has also edited a volume on Bob Dylan in Norwegian (with Botvar and Kvalvaag) and since 2011 has been responsible for a popular lecture series on Dylan at History of Ideas.

Erling Aadland

Erling Aadland has published a number of books on poetry and literary theory, among them books about Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. Latest monograph: The world of Literature, an Examination of Literature’s Antinomies, Vidarforlaget: Oslo, 2019. Book about Dylan: "And the Moon Is High", Attempting to Read Bob Dylan, Ariadne: Bergen, 1998. A number of essays on Dylan, including: “Work, Performance and Performancework”, Bøygen 2/2007; “We are not there (1967)”, Agora 1–2/2007; “One Big Prison Yard”, on (in)justice in some Dylan-songs”, Bøygen 3/2008; “Dylan and Love”, in: Bob Dylan, mannen, myten og musikken, Dreyer: Oslo, 2011; “He Got the Skills and He Got the Guts, Bob Dylan’s Alternating Interaction with the Blues”, Agora 1–2/2013.

Pål Ketil Botvar

Pål Ketil Botvar gained his PhD in political science from the University of Oslo, 2009. He is professor in sociology of religion at the faculty of humanities and education, University of Agder, Norway. Botvar has been co-editor on Bob Dylan – mannen, myten og musikken (The man, the myth and the music), together with R. Aasgaard and R. W. Kvalvaag. He has also written two articles about Bob Dylan: «Med Bob Dylan som liturg», 2013 ("Bob Dylan as Officiant"), and "With God on Our Side. Bob Dylan i norsk kirkeliv", 2013 ("With God on Our Side. Bob Dylan in Norwegian church life").

Gisle Selnes

Gisle Selnes is professor in Comparative literature at the University of Bergen, Norway, where he also directs the Research group for Radical Philosophy and literature (RFL). Selnes has written numerous articles on literary, philosophical, cultural and historical issues, ranging from colonial Latin American writings to Lacanian psychoanalysis. His books include Det fjerde kontinentet. Essays om America og andre fremmede fenomener (The Fourth Continent. Essays on America and Others Strange Phenomena, 2010), on the topic of discovery, critical theory and the origins of the essay as a genre; an annotated translation of César Vallejo’s Trilce; and the voluminous Den store sangen. Kapitler av en bok om Bob Dylan (The Everlasting Song. Chapters from a Book on Bob Dylan, 2016). In addition, Selnes has published a number of popular essays on Dylan in the press and lectured widely on Dylan’s poetics of song lyrics to an academic as well as to a more general audience.

Anders Thyrring Andersen

Anders Thyrring Andersen is Master of Arts, Comparative Literature, parish priest at Vor Frue Kirke in Aarhus, Denmark. Publications on Bob Dylan: Hvor dejlige havfruer svømmer. Om Bob Dylans digtning, Syddansk Universitetsforlag 2013; “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”, Geni og apostel. Litteratur og teologi, Anis 2006; “En fortjent Nobelpris”, Studenterkredsen no. 1, January 2019; a number of newspaper articles and appearances on National Public Radio. Has written a lot about the relationship between literature and Christianity, among other titles Polspænding. Forførelse og dialog hos Martin A. Hansen, Gyldendal 2011, and At forføre til tavshed. Søren Kierkegaard præsenteret, Dansklærerforeningen 2002. Recipient of Blicherprisen 2009 and Martin A. Hansen Prisen 2011.

Petter Fiskum Myhr

Petter Fiskum Myhr gained his cand. philol. in literature from the University of Bergen. He has worked as a journalist and editor for the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. He was the first director of Rockheim, the national museum for popular music in Norway. Since 2013 he has been the director for Trondheim International Olavsfest. Petter Fiskum Myhr has written and contributed to several books about Bob Dylan, among them: Bob Dylan – jeg er en annen, Oslo: Historie og Kultur 2011, Bob Dylan. Mannen, myten og musikken. Oslo: Dreyer Forlag, 2011 and Bob Dylan Leksikon. Oslo: Historie & Kultur, 2012.

CHAPTERS (PDF TO DOWNLOAD)

Introduction: Bob Dylan and Religion: New Perspectives from the North Country

Robert W. Kvalvaag, Geir Winje

Chapter 1: "Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)": A Window into Bob Dylan's Existential and Religious World

Reidar Aasgaard

Chapter 2: "The Titanic sails at dawn": Bob Dylan, "Tempest", and the Apocalyptic Imagination

Robert W. Kvalvaag

Chapter 3: Against Liberals: Multi-layered and Multi-directed Invocation in Bob Dylan's Christian Songs

Erling Aadland

Chapter 4: When the Wind is the Answer. The Use of Bob Dylan Songs in Worship Services in Protestant Churches

Pål Ketil Botvar

Chapter 5: The Visual Dylan: Religious Art, Social Semiotics and Album Covers

Geir Winje

Chapter 6: Bob Dylan's Conversions: The "Gospel Years" as Symptom and Transition

Gisle Selnes

Chapter 7: Hard Rain: The End of Times and Christian Modernism in the work of Bob Dylan

Anders Thyrring Andersen

Chapter 8: Bob Dylan's Ten Commandments – a Method for Personal Transformation

Petter Fiskum Myhr

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

Robert W. Kvalvaag

Robert W. Kvalvaag is professor at Oslo Metropolitan University, where he teaches religious studies at the Faculty of Teacher Education and International Studies. He has published three books (in Norwegian): From Moses to Marley, The divine I, and The Eleventh Commandment: Religion and Rock and Roll. Together with Pål Ketil Botvar and Reidar Aasgaard he also edited and contributed to Bob Dylan: The Man, the Myth and the Music. The writer of numerous articles on religion and popular culture published in anthologies and journals, his output has included works on Dylan’s use of the Bible in the early songs, and a study of the influence of Hal Lindsey on Dylan’s oeuvre in the so-called Gospel period.

Geir Winje

Geir Winje is professor in the science of religion. He works at the University of South-Eastern Norway, mostly with teacher education on different levels. He does research and publishes on three main fields: didactics of religion, art and religion, and modernity and religion. Some central books: Felles, grunnleggende verdier? Menneskerettigheter og religionspluralisme i skolen (Common, basic values? Human Rights and religious pluralism in school, 2017), Guddommelig skjønnhet. Kunst i religionene (Divine Beauty. Art in the Religions, 2nd ed. 2012), Hekser og healere. Religion og spiritualitet i det moderne (Whitches and Healers. Religion and Spirituality in Modernity, 2007).

Reidar Aasgaard

Reidar Aasgaard is Professor of Intellectual History at the Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas (IFIKK), University of Oslo. He has published books and articles in English and Norwegian on the history of childhood, the New Testament, Late Antiquity, and early Christian apocrypha. He has worked as a Bible translator and translated classical texts from Greek and Latin into Norwegian. Aasgaard has also edited a volume on Bob Dylan in Norwegian (with Botvar and Kvalvaag) and since 2011 has been responsible for a popular lecture series on Dylan at History of Ideas.

Erling Aadland

Erling Aadland has published a number of books on poetry and literary theory, among them books about Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. Latest monograph: The world of Literature, an Examination of Literature’s Antinomies, Vidarforlaget: Oslo, 2019. Book about Dylan: "And the Moon Is High", Attempting to Read Bob Dylan, Ariadne: Bergen, 1998. A number of essays on Dylan, including: “Work, Performance and Performancework”, Bøygen 2/2007; “We are not there (1967)”, Agora 1–2/2007; “One Big Prison Yard”, on (in)justice in some Dylan-songs”, Bøygen 3/2008; “Dylan and Love”, in: Bob Dylan, mannen, myten og musikken, Dreyer: Oslo, 2011; “He Got the Skills and He Got the Guts, Bob Dylan’s Alternating Interaction with the Blues”, Agora 1–2/2013.

Pål Ketil Botvar

Pål Ketil Botvar gained his PhD in political science from the University of Oslo, 2009. He is professor in sociology of religion at the faculty of humanities and education, University of Agder, Norway. Botvar has been co-editor on Bob Dylan – mannen, myten og musikken (The man, the myth and the music), together with R. Aasgaard and R. W. Kvalvaag. He has also written two articles about Bob Dylan: «Med Bob Dylan som liturg», 2013 ("Bob Dylan as Officiant"), and "With God on Our Side. Bob Dylan i norsk kirkeliv", 2013 ("With God on Our Side. Bob Dylan in Norwegian church life").

Gisle Selnes

Gisle Selnes is professor in Comparative literature at the University of Bergen, Norway, where he also directs the Research group for Radical Philosophy and literature (RFL). Selnes has written numerous articles on literary, philosophical, cultural and historical issues, ranging from colonial Latin American writings to Lacanian psychoanalysis. His books include Det fjerde kontinentet. Essays om America og andre fremmede fenomener (The Fourth Continent. Essays on America and Others Strange Phenomena, 2010), on the topic of discovery, critical theory and the origins of the essay as a genre; an annotated translation of César Vallejo’s Trilce; and the voluminous Den store sangen. Kapitler av en bok om Bob Dylan (The Everlasting Song. Chapters from a Book on Bob Dylan, 2016). In addition, Selnes has published a number of popular essays on Dylan in the press and lectured widely on Dylan’s poetics of song lyrics to an academic as well as to a more general audience.

Anders Thyrring Andersen

Anders Thyrring Andersen is Master of Arts, Comparative Literature, parish priest at Vor Frue Kirke in Aarhus, Denmark. Publications on Bob Dylan: Hvor dejlige havfruer svømmer. Om Bob Dylans digtning, Syddansk Universitetsforlag 2013; “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”, Geni og apostel. Litteratur og teologi, Anis 2006; “En fortjent Nobelpris”, Studenterkredsen no. 1, January 2019; a number of newspaper articles and appearances on National Public Radio. Has written a lot about the relationship between literature and Christianity, among other titles Polspænding. Forførelse og dialog hos Martin A. Hansen, Gyldendal 2011, and At forføre til tavshed. Søren Kierkegaard præsenteret, Dansklærerforeningen 2002. Recipient of Blicherprisen 2009 and Martin A. Hansen Prisen 2011.

Petter Fiskum Myhr

Petter Fiskum Myhr gained his cand. philol. in literature from the University of Bergen. He has worked as a journalist and editor for the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. He was the first director of Rockheim, the national museum for popular music in Norway. Since 2013 he has been the director for Trondheim International Olavsfest. Petter Fiskum Myhr has written and contributed to several books about Bob Dylan, among them: Bob Dylan – jeg er en annen, Oslo: Historie og Kultur 2011, Bob Dylan. Mannen, myten og musikken. Oslo: Dreyer Forlag, 2011 and Bob Dylan Leksikon. Oslo: Historie & Kultur, 2012.

The long, harsh Fimbul winter is not a myth

Probably half of Norway and Sweden’s population died. Researchers now know more and more about the catastrophic year of 536.

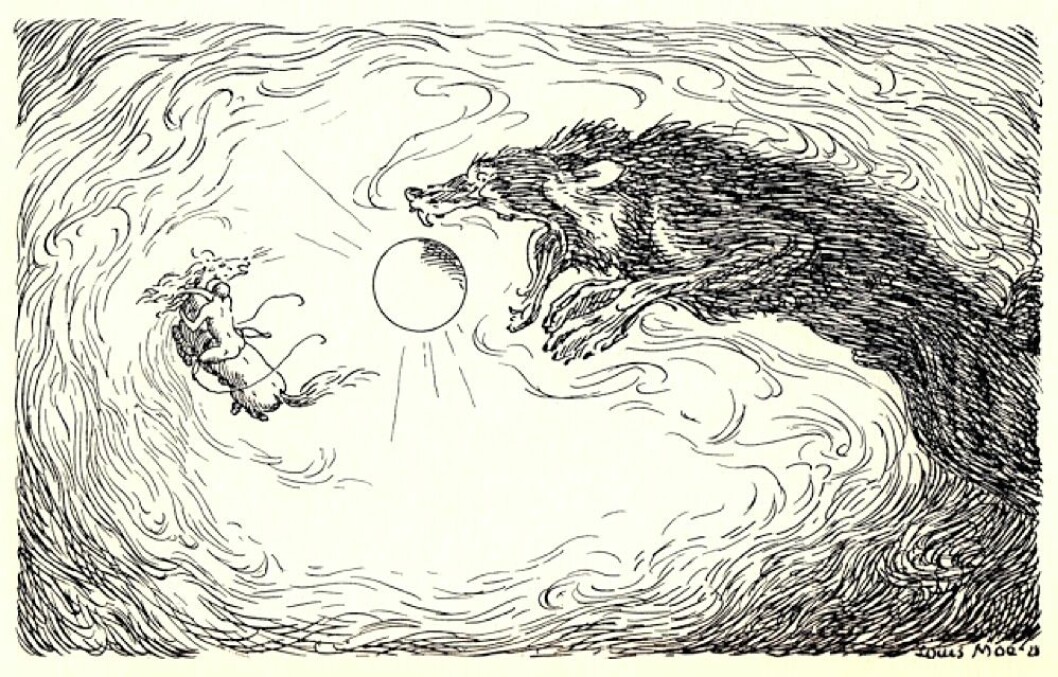

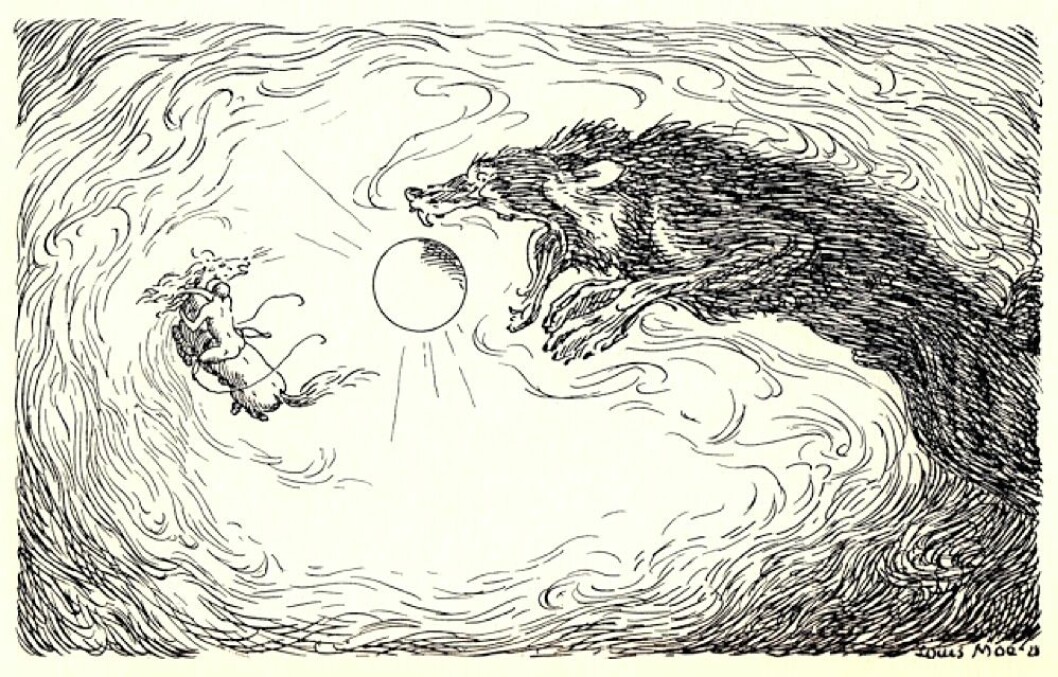

The Fenris wolf swallows the sun. The climate disaster that began the year 536 was surely the most dramatic cooling of the Earth that humans, animals and plants have experienced in the last two thousand years. It was likely due to two large volcanic explosions, which every few years sent huge amounts of fine dust high into the atmosphere. There was dust for several years. The sun disappeared. This became another story in the imagination and myths of men. (Drawing: Louis Moe)

NASA and a Swedish archaeologist

The new hunt for the Fimbul winter began with the US space agency NASA, in 1983.

“The winter called the Fimbul winter is coming. Snow flies from everywhere. There are strong, cold and sharp winds. No living thing enjoys the sun. There are three such winters — without summers in between,” Snorre writes in his book Edda. The Fimbul winter (fimbulvetr) was a warning that Ragnarok, the end of the world, was coming. Many have wondered if the myth of the Fimbul winter could be based on something that really happened. Now scientists know that this is the case.

Several years with no summer

The Fimbul winter then, meant several years in succession without a summer — which would have consequences about which we can only speculate for people who lived in the far north 1500 years ago.

Gräslund was also the first to estimate that the population of Sweden was halved in the 500s.

In the early years, many did not believe Gräslund's hypothesis.

In 2007 he publishes the article “Fimbulvintern, Ragnarök och klimatkrisen år 536–537 e. Kr.” (Fimbulvintern, Ragnarök and the climate crisis in the year 536–537 AD) in the Swedish journal Saga och sed.

After that, researchers began their hunt for the Fimbul winter in earnest.

Natural scientists and archaeologists make discoveries

In recent years, many discoveries have been made that clearly suggest that Bo Gräslund is right.

In Norway, pollen has been found deep in several bogs, evidence of a dramatic event that clearly changed the cultural landscape for a long time afterwards.

Tree rings from old trees provide another important clue.

Now that archaeologists know what to look for, these scientists are also finding more and more clues in their material. Today, archaeologists see that something dramatic happened to the farmsteads in Norway and Sweden 1500 years ago.

People moved. Or they disappeared. There are almost no grave finds from this period. Fine jewellery was no longer made. Beautiful pottery traditions in western Norway ceased.

Life seems miserable.

Also, more gold was sacrificed to the gods.

People left the mountains

Per Sjögren works as a paleoecologist at the Tromsø University Museum. He specializes in looking for clues about life from the past.

It was during his work on a major research project that examined changes in the Norwegian mountain cultural landscape that Sjögren and colleagues came on the trail of the Fimbul winter in Norway.

In pollen samples taken from boggy soil in the mountains, they saw clear traces of a dramatic climate event 1500 years ago.

“We found the first traces of the Fimbul winter in northern Norway. Eventually we found the same thing in southern Norway,” Sjögren says.

“We see that the landscape has grown back. That people and animals must have left the cultural landscapes they had used in the mountains,” he says.

Who left Storesætra in Stryn?

Kari Loe Hjelle is professor of natural history at the University of Bergen. She is interested in what pollen and other evidence from the past can tell us about people's lives — at a time when there are no written sources about life in Norway.

Hjelle describes a diagram that was created by paleoecologists when they examined the amounts of grass and tree pollen deep in the soil at Storesætra in Stryn. This was a sæter, or summer farm, just below Jostedalsbreen, in an area that people have used since the Stone Age.

The diagram clearly shows how people used this landscape between year 0 and year 500. The pollen record shows lots of grass and smaller trees.

Then something happens in the 500s. Grass pollen decreases dramatically. The trees were coming back.

Coal dust is another indication that people are using a landscape. This also disappears from Storesætra in Stryn in the 500s.

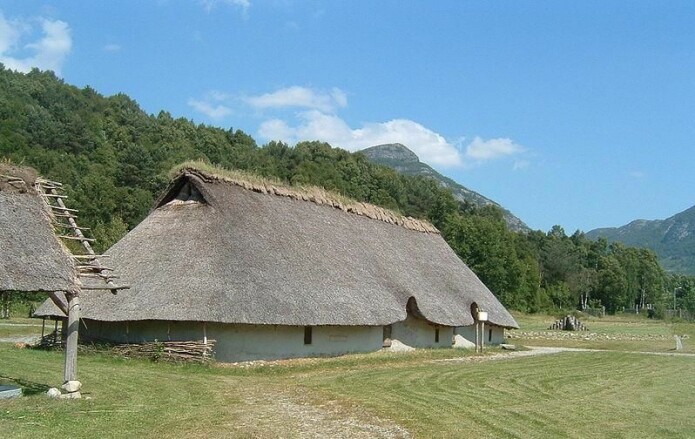

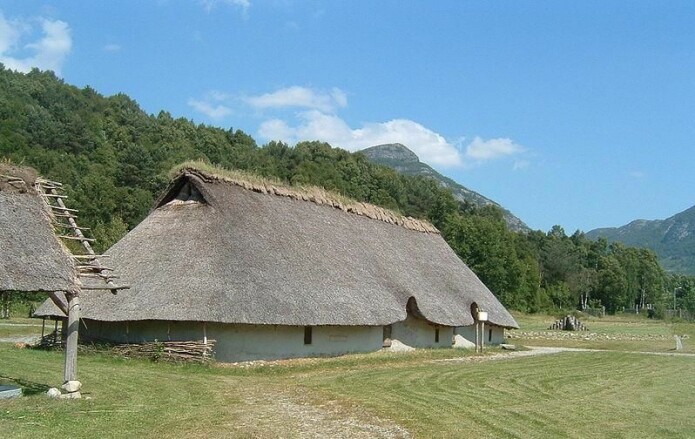

Storesætra in Stryn (Sogn og Fjordane) as it looks today. People have been using this landscape ever since the Stone Age. The pollen samples were taken from the hill in the middle of the summer farm.

Massive devastation of farms in Norway

Frode Iversen is Professor of Archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo.

“From the 1960s, it has been known among archaeologists in Norway that there was a massive devastation of farms in Norway from the mid-500s. This is a known phenomenon, especially in Rogaland County,” he says.

But why were the farms ruined and abandoned?

It has been speculated that the Justinian plague that struck the world at that time also came all the way to Norway.

“There was a lot of attention to this among Norwegian archaeologists decades ago. Since then, we haven’t thought about it much, until it again became topical because of Bo Gräslund’s new theory on the Fimbul winter,” he says.

Frode Iversen is an archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, and is one of the researchers who has been most interested in the theory of the Fimbul winter in Norway. (Photo: UiO)

“We see a very sharp decline in activity in Norway in the 500s,” Iversen says.

Nearly 90 per cent fewer discoveries

Morten Vetrhus wrote his master’s thesis at the University of Bergen on what happened during the transition from the Migration Period to Merovingian Period — in other words, before and after about 550.

He reports a sharp decline in the number of sites where archaeologists found something interesting. The decline in discovery sites was as much as 70 per cent.

Even greater was the decline in the number of archaeological finds in Rogaland from the Migration Period to the Merovingian Period. This decline was 87 per cent.

This despite the fact that the Merovingian Period lasted a hundred years longer than the Migration Period. Even in a fertile area like Jæren, parts of the landscape was completely emptied of people.

“This is a very strong decline. What happened to these people? Why do we stop finding evidence of them?” Iversen asks.

Smaller farms abandoned

Climate or plague?

Iversen now wonders if it was the climate disaster alone that destroyed the population.

Or was it — as more and more scientists are tending to believe— a combination of climate and a serious epidemic?

The Justinian plague hit Southern Europe in the year 541.

There’s no evidence that it also reached all the way to the Nordic countries. But researchers who have opened graves have recently been able to establish that the plague came to Germany. That makes it not unlikely that it also hit Norway.

The bacterium from the 500s — Yersina pestis — is the same that hit Europe during the Black Death in the 1300s.

In the vast city of Constantinople, it is estimated that about 40 per cent of the inhabitants died during the Justinian plague in the years 541 and 542.

The Justinian plague in northern Norway?

One of the world's foremost research communities on plague is found today at the University of Oslo under the leadership of Professor Nils Christian Stenseth.

Researchers there have determined that the plague bacterium must have been imported into Europe time and again. They also see that climate has a lot to do with the development of plagues. As the climate became colder, the rats died. Then the fleas that carried the plague shifted to people.

"If we are going to find traces of plague on people from as far back as the 500s, my tip is that we investigate skeletons in northern Norway," Iversen said.

The climate is cooler in northern Norway and skeletons are better preserved. In addition, some bone remnants in northern Norway are found in calcareous shell sand.

Iversen warns that scientists will need a lot of luck to find plague bacteria in people who lived 1500 years ago.

The entire Norrland depopulated

To find more pieces of the puzzle surrounding the Fimbul winter, we now travel to Sweden.

In recent years, several researchers have taken an interest in what Swedish scientists now commonly call "the incident in 536".

Now that Swedish archaeologists know what to look for from this time period, they, like their Norwegian counterparts, they find evidence of the disaster.

Archaeologists see that a large number of Swedish farms were abandoned in the mid-500s. Large areas where animals had grazed are being repopulated by trees — just like in Norway.

The northern part of Sweden — Norrland — may have been completely depopulated.

Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist is both a historian and climate scientist at Stockholm University. He is particularly interested in the volcanic explosions he believes must have taken place in the years 536 and 540. Ljungqvist has recently published a popular science book on how people through history have been affected by the climate. (Photo: Private)

Half of Swedish farms abandoned

Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist is both a historian and climate scientist at Stockholm University.

“It is now clear from Swedish archaeological research that perhaps as much as 50 per cent of the population disappeared from Mälardalen, Öland and Gotland. Almost half of all buildings were abandoned,” he says.

Climate scientists believe there must have been a huge volcanic eruption in the year 536.

“It probably happened somewhere in the non-tropical part of the northern hemisphere. The outbreak caused large quantities of aerosols (tiny particles) to be sent high into the atmosphere,” he said.

This was followed by an even bigger volcanic disaster in the year 540.

“This must have happened somewhere near the Equator. Maybe it was El Chichón volcano in southern Mexico,” he said.

The tiny particles from the two volcanic eruptions remained in the atmosphere for several years, leading to strong cooling in the northern hemisphere. Ljungqvist points out that there are now a number of studies of annual rings in old trees that confirm this.

He points out that the cumulative effect of two huge volcanic eruptions in the years 536 and 540 was what made this cooling quite exceptional and very long lasting.

“Today we know that this is probably the most severe cooling the Earth has experienced in more than 2000 years,” says Ljungqvist.

Frost in trees in the middle of summer

It was so cold that frost formed inside trees in the middle of summer.

Traces of this have been found in Russia, among other places. It is very rare for trees to freeze internally during the summer.

“The cooling may have been 3-4 degrees on average in the summer of 536 and somewhat less the years that followed. About the same time, the cooling resumed in the year 540. It may not sound like much. But the cold was hardly spread evenly throughout the summer. Certain periods in the summer were probably extra cold, while other parts of the summer probably had normal temperatures,” Ljungqvist says.

Another issue was the low sunlight. Sunlight was unable to penetrate the ash layer in the atmosphere. Without sunlight, plants failed. People were not able to grow food. They couldn’t grow hay for their animals.

Ljungqvist notes that the cold summers after 536 in some places seem to have experienced heavy rainfall.

Grain matured, but rotted.

Then came the plague

There are no written sources from the Nordic countries from as early as the 500s.

In Constantinople, the historian Prokopios writes of a constant solar eclipse.

From Ireland there are depictions of famine.

From China there are written sources that speak of snow in the middle of summer.

Then — in the year 541 — the Justinian plague comes to Europe.

“In southern Europe we know this plague epidemic was as brutal as the Black Death 800 years later. There is a lot of evidence that the plague in the 500s also reached Northern Europe, although we do not have written sources that describe it,” says Ljungqvist.

In 2013, German scientists were able to confirm that three people buried in today's Germany were infected by the pest bacterium Yersina pestis during this period.

If the plague reached north of the Alps, Ljungqvist considers it likely that it also reached Scandinavia.

“Together, the dramatic cooling of the climate and the Justinian plague may have created a disaster for people that was even greater than the Black Death,” Ljungqvist thinks. He has published a popular science book in Sweden, Klimatet och männskan under 12000 år, (Climate and Man over 12,000 Years).

Ljungqvist also co-authored a research article in 2016 in the journal Nature Geoscience. Here the researchers used the name Late Antique Little Ice Age to describe the period from 536 to 660.

A dramatic transition

In Norway, the centuries before the year 550 are called the Migration Period. The time after 550 and up to the year 800 is called the Merovingian Period. Then comes the Viking Age.

The transition from the Migration Period to the Merovingian Period around the year 550 also marks the transition from the older Iron Age to the younger Iron Age.

The catastrophe thus occurred in the transition between the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period, and in the transition from older to younger Iron Age.

This is transition where researchers — as you probably already have understood —have suspected for some time that something dramatic must have happened.

Now we know what this dramatic happening was.

A typical Scandinavian gold braided bracteate with a figure of a horse and reverse swastika at the bottom. The runes on the bracteate say Alu. The bracteate is from the time around to the climate disaster. The swastika is an ancient symbol in many cultures, including in Scandinavia. This bracteate was found in Sweden.

The graves that disappeared

Here are some other indications from Norway of the disaster from 1500 years ago:

In Norway, the number of burial finds at the beginning of the Merovingian Period falls by at least 90 per cent, compared with the number of finds from the Migration Period. To repeat: This was the time before and after the disaster.

This change could certainly be due to new burial customs. But an equally likely cause is the combined effect of the volcanic eruptions in 536 and 540, and the Justinian plague.

In Denmark, archaeologist Morten Axboe found that large quantities of gold and other precious metal jewellery were sacrificed right after the climate shock.

Axboe's theory is that these sacrifices were actions of desperate people. They sought to mollify higher powers and asked them to bring the sun back into the sky.

A strangely quiet time

An article about the Merovingian Period (550-800) on Norgeshistorie.no is entitled “Hundre års tystnad,” which translates as “A hundred years of silence.”

Per Ditlof Fredriksen is an associate professor at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo and authored the article.

Fredriksen calls the first part of this historical period a strangely quiet time in Norway. Like Iversen at the Museum of Cultural History, he points out that from the years 550 to 650 there are very few archaeological finds in Norway.

It’s not just that people stop building houses and burying their dead.

It also looks like people are forgetting how to make important tools. Tools they definitely needed.

It is only beginning around the year 650 that archaeologists see that human life in Norway was once again beginning to return to normal. But then much of the technology was new. A lot of knowledge had obviously disappeared. For example, people started making iron in a whole new way.

In Rogaland and the surrounding areas, until the disaster 1500 years ago, there were many skilled goldsmiths.

Both they and their craft disappeared.

The same thing happened to the many talented potters who had lived in western Norway before the Merovingian Period, from Jæren in the south to Sogn in the north.

It would take another thousand years before equally fine pottery was made in Norway.

Which volcanoes were they?

The clearest indications that there were two different volcanic eruptions in succession that created the Fimbul winter are from ice cores obtained from inland ice sheets on Greenland.

Some researchers have suggested the Ilopango volcano in El Salvador as the cause of the first disaster in 536. Another alternative is Krakatau in Indonesia.

Instead, Ljungqvist thinks El Chichón in southern Mexico was the most likely cause, based on what researchers know today.

In 1982 it turned out that El Chichón is still a deadly volcano. An eruption at that time cost 2000 people their lives. Prior to this, the volcano had not erupted since 1360 and people were not prepared for the sleeping giant to wake up.

There’s little doubt that aerosols released by volcanoes into the atmosphere can affect the Earth's climate today.

The higher in the atmosphere the aerosols reach, the longer the effect will last. What is probably decisive is whether the aerosols reach the stratosphere, or altitudes over 10,000 metres — which is the altitude where most of the air traffic is.

Huge volcanic eruptions are not uncommon

The United Nations Climate Panel (IPCC) wrote in a report from 2013 on how climate change over the last 2000 years may have been affected by volcanoes. Much of the knowledge researchers today have about the effects of volcanic eruptions back in time comes from ice cores gleaned from Greenland and Antarctica.

The researchers behind the IPCC report found that there have only been two or three hundred years since the Viking Age without very large volcanic eruptions that have affected the climate significantly.

The fact that the whole of the last century — the 20th century — was without gigantic volcanic eruptions may have helped make this be something that few of us imagine could happen again.

But it will certainly happen again.

Giant volcanic eruptions that affect the climate over a long period are actually not very rare.

It’s common for the climate and temperature of the Earth to be affected for one to three years after a huge volcanic eruption, depending on the number of aerosols that reach far into the atmosphere.

If several such gigantic volcanic eruptions were to occur in succession — as they probably did in years 536 and 540 — the impact on the climate would be even greater.

If this happens again, there are a lot more people on Earth who will need food.

On the other hand, society is much better prepared for this kind of disaster. We can transport food and mostly everything else we need over long distances. The people who lived in cold Norway 1500 years ago couldn’t do this. They were completely dependent on the food they grew and the animals they raised themselves.

The year 1816 is also called "The Year Without Summer". The reason was the Indonesian volcano Tambora, which during an eruption spewed huge amounts of dust into the atmosphere. In Western Europe and eastern North America, this caused the sunlight to disappear, temperatures became colder and crops failed. The Nordic region was not hit as hard. (Photo: Jialiang Gao / Wikimedia Commons)

1816 was "The Year Without Summer"

The year 1816 has become known as "The Year Without Summer".

It was an unusually cold year in Western Europe and the eastern part of North America. There was also an unusual amount of rain. In the spring after — in 1817 —grain prices in parts of Europe doubled.

The main cause of the unusually cold summer of 1816 was the explosion of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia. But in the years before the Tambora eruption, there had been four other major volcanic eruptions, all of which had spewed a lot of dust into the atmosphere.

The natural disaster in 1816 was hardly of the same magnitude as the disaster of 536. It was nevertheless severe.

It is therefore worth noting that the consequences were not at all the same. Two hundred years ago, the world was becoming modern.

In 1816 there was extensive international trade. Ships could carry a lot of food. People in distress could go to America, and many left. Several countries had a kind of social welfare system in place that could help the very poor. National health care systems and most people had become much better at preventing plague epidemics.

If we are again struck by a disaster like the one that happened in the 500s, we would be much better equipped to face it.

A lot of scientific articles will be written about what happened. Many will write books. Millions will tweet or post on Facebook.

Many of us nevertheless still believe in myths.

But we are unlikely to ever experience a Fimbul winter again.

———

Probably half of Norway and Sweden’s population died. Researchers now know more and more about the catastrophic year of 536.

The Fenris wolf swallows the sun. The climate disaster that began the year 536 was surely the most dramatic cooling of the Earth that humans, animals and plants have experienced in the last two thousand years. It was likely due to two large volcanic explosions, which every few years sent huge amounts of fine dust high into the atmosphere. There was dust for several years. The sun disappeared. This became another story in the imagination and myths of men. (Drawing: Louis Moe)

Nancy Bazilchuk ENGLISH VERSION

https://sciencenorway.no/

Tuesday 24. december 2019 -

"First came the Fimbul winter that lasted three years. This was a warning of the coming of Ragnarok, when everything living on Earth came to an end. "

This is how the story of the long harsh winter, called the Fimbul winter in Norwegian, begins, both in Norse mythology and in the Finnish national work of epic poetry, the Kalevala.

But why are stories that warn of a frozen end-time found in Nordic mythologies?

In recent years, researchers in Norway and Sweden have found increasingly clear evidence of a disaster that struck the planet 1500 years ago.

The disaster must have hit Norwegians and Swedes extremely hard — as hard as the Black Death. The same may have happened in the Baltics, Poland and northern Germany.

The moss scientist’s theory

In 1910, the Swedish geographer and reseacher of moss Rutger Sernander first launched the theory that the Fimbul winter may have been a real event in the Nordic countries. His hypothesis was that this was due to a climate disaster between 2000 and 2500 years ago.

For a few years, people listened to Sernander and his ideas. Then came the doubt, because archaeologists couldn’t find traces of such an ancient disaster.

We now know however, that a climate disaster struck the world — and especially the Nordic countries — just 1500 years ago.

And we know that it may have been followed by another disaster. Which might have been just as big.

Tuesday 24. december 2019 -

"First came the Fimbul winter that lasted three years. This was a warning of the coming of Ragnarok, when everything living on Earth came to an end. "

This is how the story of the long harsh winter, called the Fimbul winter in Norwegian, begins, both in Norse mythology and in the Finnish national work of epic poetry, the Kalevala.

But why are stories that warn of a frozen end-time found in Nordic mythologies?

In recent years, researchers in Norway and Sweden have found increasingly clear evidence of a disaster that struck the planet 1500 years ago.

The disaster must have hit Norwegians and Swedes extremely hard — as hard as the Black Death. The same may have happened in the Baltics, Poland and northern Germany.

The moss scientist’s theory

In 1910, the Swedish geographer and reseacher of moss Rutger Sernander first launched the theory that the Fimbul winter may have been a real event in the Nordic countries. His hypothesis was that this was due to a climate disaster between 2000 and 2500 years ago.

For a few years, people listened to Sernander and his ideas. Then came the doubt, because archaeologists couldn’t find traces of such an ancient disaster.

We now know however, that a climate disaster struck the world — and especially the Nordic countries — just 1500 years ago.

And we know that it may have been followed by another disaster. Which might have been just as big.

NASA and a Swedish archaeologist

The new hunt for the Fimbul winter began with the US space agency NASA, in 1983.

“The winter called the Fimbul winter is coming. Snow flies from everywhere. There are strong, cold and sharp winds. No living thing enjoys the sun. There are three such winters — without summers in between,” Snorre writes in his book Edda. The Fimbul winter (fimbulvetr) was a warning that Ragnarok, the end of the world, was coming. Many have wondered if the myth of the Fimbul winter could be based on something that really happened. Now scientists know that this is the case.

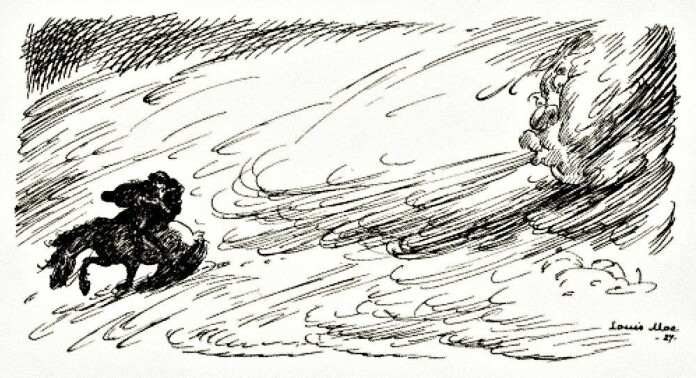

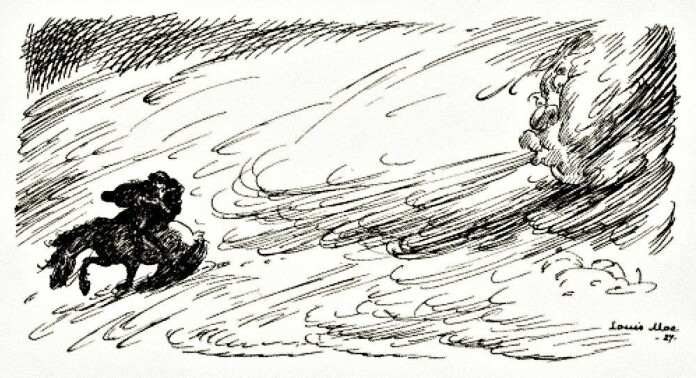

(The picture of the Fimbul winter was drawn by Louis Moe in 1929.)

At this time, two NASA scientists, Richard Stothers and Michael Rampino, published a scientific overview of known volcanic eruptions back in time. Much of their work was based on ice cores taken from ancient inland glacier ice on Greenland.

Archaeologists read the article. They understood that something very dramatic may have happened in the year 536.

Central to the new hunt for the Fimbul winter was Bo Gräslund, now a retired professor of archaeology at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Gräslund was first to suggest that the Fimbul winter was a real event, and that it took place in the years after 536. He also pointed out that the 13th century Icelandic historian Snorre in his book Edda was not only concerned that it was very cold and the winters were snowy — Snorre was also concerned because there were no summers for several years in a row.

Bo Gräslund is professor emeritus in archaeology at Uppsala University in Sweden. He was the first to suggest that the Fimbul winter may have been a climate disaster in the 500s. (Image from YouTube)

At this time, two NASA scientists, Richard Stothers and Michael Rampino, published a scientific overview of known volcanic eruptions back in time. Much of their work was based on ice cores taken from ancient inland glacier ice on Greenland.

Archaeologists read the article. They understood that something very dramatic may have happened in the year 536.

Central to the new hunt for the Fimbul winter was Bo Gräslund, now a retired professor of archaeology at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Gräslund was first to suggest that the Fimbul winter was a real event, and that it took place in the years after 536. He also pointed out that the 13th century Icelandic historian Snorre in his book Edda was not only concerned that it was very cold and the winters were snowy — Snorre was also concerned because there were no summers for several years in a row.

Bo Gräslund is professor emeritus in archaeology at Uppsala University in Sweden. He was the first to suggest that the Fimbul winter may have been a climate disaster in the 500s. (Image from YouTube)

Several years with no summer

The Fimbul winter then, meant several years in succession without a summer — which would have consequences about which we can only speculate for people who lived in the far north 1500 years ago.

Gräslund was also the first to estimate that the population of Sweden was halved in the 500s.

In the early years, many did not believe Gräslund's hypothesis.

In 2007 he publishes the article “Fimbulvintern, Ragnarök och klimatkrisen år 536–537 e. Kr.” (Fimbulvintern, Ragnarök and the climate crisis in the year 536–537 AD) in the Swedish journal Saga och sed.

After that, researchers began their hunt for the Fimbul winter in earnest.

Natural scientists and archaeologists make discoveries

In recent years, many discoveries have been made that clearly suggest that Bo Gräslund is right.

In Norway, pollen has been found deep in several bogs, evidence of a dramatic event that clearly changed the cultural landscape for a long time afterwards.

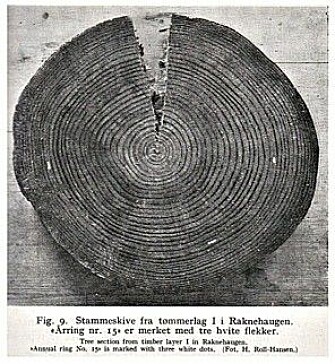

Tree rings from old trees provide another important clue.

Now that archaeologists know what to look for, these scientists are also finding more and more clues in their material. Today, archaeologists see that something dramatic happened to the farmsteads in Norway and Sweden 1500 years ago.

People moved. Or they disappeared. There are almost no grave finds from this period. Fine jewellery was no longer made. Beautiful pottery traditions in western Norway ceased.

Life seems miserable.

Also, more gold was sacrificed to the gods.

People left the mountains

Per Sjögren works as a paleoecologist at the Tromsø University Museum. He specializes in looking for clues about life from the past.

It was during his work on a major research project that examined changes in the Norwegian mountain cultural landscape that Sjögren and colleagues came on the trail of the Fimbul winter in Norway.

In pollen samples taken from boggy soil in the mountains, they saw clear traces of a dramatic climate event 1500 years ago.

“We found the first traces of the Fimbul winter in northern Norway. Eventually we found the same thing in southern Norway,” Sjögren says.

“We see that the landscape has grown back. That people and animals must have left the cultural landscapes they had used in the mountains,” he says.

Who left Storesætra in Stryn?

Kari Loe Hjelle is professor of natural history at the University of Bergen. She is interested in what pollen and other evidence from the past can tell us about people's lives — at a time when there are no written sources about life in Norway.

Hjelle describes a diagram that was created by paleoecologists when they examined the amounts of grass and tree pollen deep in the soil at Storesætra in Stryn. This was a sæter, or summer farm, just below Jostedalsbreen, in an area that people have used since the Stone Age.

The diagram clearly shows how people used this landscape between year 0 and year 500. The pollen record shows lots of grass and smaller trees.

Then something happens in the 500s. Grass pollen decreases dramatically. The trees were coming back.

Coal dust is another indication that people are using a landscape. This also disappears from Storesætra in Stryn in the 500s.

Storesætra in Stryn (Sogn og Fjordane) as it looks today. People have been using this landscape ever since the Stone Age. The pollen samples were taken from the hill in the middle of the summer farm.

(Photo: Kari Hjelle)

Massive devastation of farms in Norway

Frode Iversen is Professor of Archaeology at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo.

“From the 1960s, it has been known among archaeologists in Norway that there was a massive devastation of farms in Norway from the mid-500s. This is a known phenomenon, especially in Rogaland County,” he says.

But why were the farms ruined and abandoned?

It has been speculated that the Justinian plague that struck the world at that time also came all the way to Norway.

“There was a lot of attention to this among Norwegian archaeologists decades ago. Since then, we haven’t thought about it much, until it again became topical because of Bo Gräslund’s new theory on the Fimbul winter,” he says.

Now Iversen and colleagues have summarized much of what they know about the Fimbul winter in Norway in some of the chapters in their book "The Agrarian Life of the North 2000 BC – AD 1000". It is available (in English) free of charge as a PDF book at Cappelen Damm here.

Frode Iversen is an archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, and is one of the researchers who has been most interested in the theory of the Fimbul winter in Norway. (Photo: UiO)

“We see a very sharp decline in activity in Norway in the 500s,” Iversen says.

Nearly 90 per cent fewer discoveries

Morten Vetrhus wrote his master’s thesis at the University of Bergen on what happened during the transition from the Migration Period to Merovingian Period — in other words, before and after about 550.

He reports a sharp decline in the number of sites where archaeologists found something interesting. The decline in discovery sites was as much as 70 per cent.

Even greater was the decline in the number of archaeological finds in Rogaland from the Migration Period to the Merovingian Period. This decline was 87 per cent.

This despite the fact that the Merovingian Period lasted a hundred years longer than the Migration Period. Even in a fertile area like Jæren, parts of the landscape was completely emptied of people.

“This is a very strong decline. What happened to these people? Why do we stop finding evidence of them?” Iversen asks.

Smaller farms abandoned

The village of Landa in Forsand in Rogaland was continuously settled for more than 2,000 years — both during the Bronze Age and the Iron Age — right up to the time of the disaster in 536. Most people lived here during the Migration Period, just before people disappeared. The Bronze Age house in the picture dates from 1500 years before the disaster. But the building practices did not change much at this time.

(Photo: Hallvard Nygård / Wikimedia Commons)

Iversen believes a strategy people used to face the crisis was to abandon the small and least productive farms. Larger and more centrally located lands were instead divided into smaller production units.

A lack of labour made it difficult to maintain farm operations in Rogaland and likely in the rest of Norway at the levels it had been at before the disaster in the mid-500s.

Iversen also wonders if the mass death caused more land to be available for people who survived. This may explain why archaeologists find traces of agriculture in Norway in the latter part of the 500s that reflects more animal husbandry. This is something similar to what other historians believe happened after the Black Death around 1350.

There are also some examples of new power centres being established in Norway after the disaster.

Raknehaugen in Romerike — the largest burial mound in the Nordic countries — probably reflects this. There were fewer powerful people left in the country, but those who remained might have had greater control and were even more powerful than before the disaster. Archaeologists have found evidence of the same in Sweden.

Iversen believes a strategy people used to face the crisis was to abandon the small and least productive farms. Larger and more centrally located lands were instead divided into smaller production units.

A lack of labour made it difficult to maintain farm operations in Rogaland and likely in the rest of Norway at the levels it had been at before the disaster in the mid-500s.

Iversen also wonders if the mass death caused more land to be available for people who survived. This may explain why archaeologists find traces of agriculture in Norway in the latter part of the 500s that reflects more animal husbandry. This is something similar to what other historians believe happened after the Black Death around 1350.

There are also some examples of new power centres being established in Norway after the disaster.

Raknehaugen in Romerike — the largest burial mound in the Nordic countries — probably reflects this. There were fewer powerful people left in the country, but those who remained might have had greater control and were even more powerful than before the disaster. Archaeologists have found evidence of the same in Sweden.

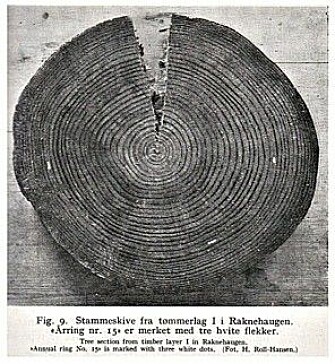

Raknehaugen in Romerike is the largest burial mound in the Nordic region. Inside the mound were logs that were probably cut in the year 551. The white lines show the annual ring from the year 536. Notice how narrow the rings are that extend further out towards the outside of the tree after this date. The photo was taken by researcher H. Roll-Hansen in 1941. Iversen, PhD candidate Josh Bostic and several colleagues have started to study the timber from Raknehaugen again, this time with completely modern methods. They hope to establish what the temperatures were — week by week — in the year 536 and in subsequent years.

Iversen has no doubt that the disaster must also have had a major impact on social structures in Scandinavia.

His theory is that the disaster hit the upper and lower layers of society the hardest.

As a consequence, after the disaster, a "middle class" grew larger. And with this, a society where people were more equal than before.

The art of goldsmithing disappears

Ingunn Røstad, also a researcher at the Museum of Cultural History, has shown that the clothes and jewellery used by the Iron Age people in the 600s and 700s were of simpler quality than from before the early 500s.

“Fine gold and silver jewellery were less common,” says Iversen.

“The jewellery that was made became simpler. It almost looks ‘homemade’.”

Iversen has no doubt that the disaster must also have had a major impact on social structures in Scandinavia.

His theory is that the disaster hit the upper and lower layers of society the hardest.

As a consequence, after the disaster, a "middle class" grew larger. And with this, a society where people were more equal than before.

The art of goldsmithing disappears

Ingunn Røstad, also a researcher at the Museum of Cultural History, has shown that the clothes and jewellery used by the Iron Age people in the 600s and 700s were of simpler quality than from before the early 500s.

“Fine gold and silver jewellery were less common,” says Iversen.

“The jewellery that was made became simpler. It almost looks ‘homemade’.”

Climate or plague?

Iversen now wonders if it was the climate disaster alone that destroyed the population.

Or was it — as more and more scientists are tending to believe— a combination of climate and a serious epidemic?

The Justinian plague hit Southern Europe in the year 541.

There’s no evidence that it also reached all the way to the Nordic countries. But researchers who have opened graves have recently been able to establish that the plague came to Germany. That makes it not unlikely that it also hit Norway.

The bacterium from the 500s — Yersina pestis — is the same that hit Europe during the Black Death in the 1300s.

In the vast city of Constantinople, it is estimated that about 40 per cent of the inhabitants died during the Justinian plague in the years 541 and 542.

The Justinian plague in northern Norway?

One of the world's foremost research communities on plague is found today at the University of Oslo under the leadership of Professor Nils Christian Stenseth.

Researchers there have determined that the plague bacterium must have been imported into Europe time and again. They also see that climate has a lot to do with the development of plagues. As the climate became colder, the rats died. Then the fleas that carried the plague shifted to people.

"If we are going to find traces of plague on people from as far back as the 500s, my tip is that we investigate skeletons in northern Norway," Iversen said.

The climate is cooler in northern Norway and skeletons are better preserved. In addition, some bone remnants in northern Norway are found in calcareous shell sand.

Iversen warns that scientists will need a lot of luck to find plague bacteria in people who lived 1500 years ago.

The entire Norrland depopulated

To find more pieces of the puzzle surrounding the Fimbul winter, we now travel to Sweden.

In recent years, several researchers have taken an interest in what Swedish scientists now commonly call "the incident in 536".

Now that Swedish archaeologists know what to look for from this time period, they, like their Norwegian counterparts, they find evidence of the disaster.

Archaeologists see that a large number of Swedish farms were abandoned in the mid-500s. Large areas where animals had grazed are being repopulated by trees — just like in Norway.

The northern part of Sweden — Norrland — may have been completely depopulated.

Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist is both a historian and climate scientist at Stockholm University. He is particularly interested in the volcanic explosions he believes must have taken place in the years 536 and 540. Ljungqvist has recently published a popular science book on how people through history have been affected by the climate. (Photo: Private)

Half of Swedish farms abandoned

Fredrik Charpentier Ljungqvist is both a historian and climate scientist at Stockholm University.

“It is now clear from Swedish archaeological research that perhaps as much as 50 per cent of the population disappeared from Mälardalen, Öland and Gotland. Almost half of all buildings were abandoned,” he says.

Climate scientists believe there must have been a huge volcanic eruption in the year 536.

“It probably happened somewhere in the non-tropical part of the northern hemisphere. The outbreak caused large quantities of aerosols (tiny particles) to be sent high into the atmosphere,” he said.

This was followed by an even bigger volcanic disaster in the year 540.

“This must have happened somewhere near the Equator. Maybe it was El Chichón volcano in southern Mexico,” he said.

The tiny particles from the two volcanic eruptions remained in the atmosphere for several years, leading to strong cooling in the northern hemisphere. Ljungqvist points out that there are now a number of studies of annual rings in old trees that confirm this.

He points out that the cumulative effect of two huge volcanic eruptions in the years 536 and 540 was what made this cooling quite exceptional and very long lasting.

“Today we know that this is probably the most severe cooling the Earth has experienced in more than 2000 years,” says Ljungqvist.

Frost in trees in the middle of summer

It was so cold that frost formed inside trees in the middle of summer.

Traces of this have been found in Russia, among other places. It is very rare for trees to freeze internally during the summer.

“The cooling may have been 3-4 degrees on average in the summer of 536 and somewhat less the years that followed. About the same time, the cooling resumed in the year 540. It may not sound like much. But the cold was hardly spread evenly throughout the summer. Certain periods in the summer were probably extra cold, while other parts of the summer probably had normal temperatures,” Ljungqvist says.

Another issue was the low sunlight. Sunlight was unable to penetrate the ash layer in the atmosphere. Without sunlight, plants failed. People were not able to grow food. They couldn’t grow hay for their animals.

Ljungqvist notes that the cold summers after 536 in some places seem to have experienced heavy rainfall.

Grain matured, but rotted.

Then came the plague

There are no written sources from the Nordic countries from as early as the 500s.

But in Italy, historian Flavius Cassidorus in 536 reports a sky full of dark clouds and sunlight lasting just a few hours a day.

In Constantinople, the historian Prokopios writes of a constant solar eclipse.

From Ireland there are depictions of famine.

From China there are written sources that speak of snow in the middle of summer.

Then — in the year 541 — the Justinian plague comes to Europe.

“In southern Europe we know this plague epidemic was as brutal as the Black Death 800 years later. There is a lot of evidence that the plague in the 500s also reached Northern Europe, although we do not have written sources that describe it,” says Ljungqvist.

In 2013, German scientists were able to confirm that three people buried in today's Germany were infected by the pest bacterium Yersina pestis during this period.

If the plague reached north of the Alps, Ljungqvist considers it likely that it also reached Scandinavia.

“Together, the dramatic cooling of the climate and the Justinian plague may have created a disaster for people that was even greater than the Black Death,” Ljungqvist thinks. He has published a popular science book in Sweden, Klimatet och männskan under 12000 år, (Climate and Man over 12,000 Years).

Ljungqvist also co-authored a research article in 2016 in the journal Nature Geoscience. Here the researchers used the name Late Antique Little Ice Age to describe the period from 536 to 660.

A dramatic transition

In Norway, the centuries before the year 550 are called the Migration Period. The time after 550 and up to the year 800 is called the Merovingian Period. Then comes the Viking Age.

The transition from the Migration Period to the Merovingian Period around the year 550 also marks the transition from the older Iron Age to the younger Iron Age.

The catastrophe thus occurred in the transition between the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period, and in the transition from older to younger Iron Age.

This is transition where researchers — as you probably already have understood —have suspected for some time that something dramatic must have happened.

Now we know what this dramatic happening was.

A typical Scandinavian gold braided bracteate with a figure of a horse and reverse swastika at the bottom. The runes on the bracteate say Alu. The bracteate is from the time around to the climate disaster. The swastika is an ancient symbol in many cultures, including in Scandinavia. This bracteate was found in Sweden.

(Photo: Sigune / Wikimedia Commons)

The graves that disappeared

Here are some other indications from Norway of the disaster from 1500 years ago:

In Norway, the number of burial finds at the beginning of the Merovingian Period falls by at least 90 per cent, compared with the number of finds from the Migration Period. To repeat: This was the time before and after the disaster.

This change could certainly be due to new burial customs. But an equally likely cause is the combined effect of the volcanic eruptions in 536 and 540, and the Justinian plague.

In Denmark, archaeologist Morten Axboe found that large quantities of gold and other precious metal jewellery were sacrificed right after the climate shock.

Axboe's theory is that these sacrifices were actions of desperate people. They sought to mollify higher powers and asked them to bring the sun back into the sky.

A strangely quiet time

An article about the Merovingian Period (550-800) on Norgeshistorie.no is entitled “Hundre års tystnad,” which translates as “A hundred years of silence.”

Per Ditlof Fredriksen is an associate professor at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo and authored the article.

Fredriksen calls the first part of this historical period a strangely quiet time in Norway. Like Iversen at the Museum of Cultural History, he points out that from the years 550 to 650 there are very few archaeological finds in Norway.

It’s not just that people stop building houses and burying their dead.

It also looks like people are forgetting how to make important tools. Tools they definitely needed.