“I like the things you post on Facebook,” my Grandpa told me on a phone call a few weeks ago.

“I just hate the stuff people comment—it makes me lose hope in people.”

My Grandpa’s not the type to doom-scroll Twitter. But he does check in on my social accounts from time to time. Back in 2017, when I was running for Governor, he came across a Facebook post—with 1700 shares—claiming I was a part of a global Muslim conspiracy to take over America. The kicker? That post was shared by the dude who played Hercules on TV back in the 90s, Kevin Sorbo. Until then, Grandpa and I had both been fans.

The kind of hateful disinformation—as vile as it is violent—bubbled over in real life on January 6th at our nation’s Capitol, but it has been seething online for years. The nature of social media makes us believe that the hatred it fuels is far more common than it really is—even as it grows and amplifies it. Given the impact it's had on our politics and our public health through the course of this pandemic, it’s time to do something about it.

A Selection Bias Amplification Machine.

“Selection bias” is one of the most important sources of error in epidemiology. It’s what happens when the people you include in a study aren’t representative of the population you are studying because of the way participants became a part of your study. Your study sample becomes enriched for some critical feature as a function of how it was generated. For example, if you wanted to study the relationship between car ownership and daily exercise in the United States, and you only included people who live in New York City, you might get a biased perspective. People in New York benefit from access to incredible public transit in the form of a subway system, while things like the cost of parking, terrible traffic, and the general hassle of owning a car in the city make car ownership prohibitive. That particular relationship between New York City and car ownership biases whatever inference you wanted to make in your study and leaves you with erroneous conclusions.

Social media is a public opinion selection bias amplification machine. The only people who usually comment are the folks who have something specific to say—good or bad, but usually bad. And because social media algorithms usually enrich content with the most reactions, and the most extreme comments usually get the most reactions, social media feeds you vitriol. You might think this is a design flaw. Nope: algorithmic sorting is a design feature. After all, social media companies want you to respond—so they send you the things that people like you were most likely to have responded to, good, bad, or ugly. That might be a cute cat video. Or it might be a rant from a far-right social media troll who makes you want to puke. Nausea, too, is a reaction.

Why do they do this? Because you’re not the customer they want to keep happy. You’re the product. The customer is the advertiser to which Facebook et al. are trying to sell your eyeball time (for a great book on the evolution of this business model, check out Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism). And eliciting a reaction is a sure-fire way to keep your eyeballs on the feed—so their real customers can sell you something.

The emergent phenomenon is that we’re left feeling like the world is a scary, hateful, angry place full of people who say mean things to each other. Don’t get me wrong, the world has many of those people—but the ones who don’t hate each other, aren’t angry, and don’t want you to go to hell? They’re probably not commenting. And if they are, you’re probably not seeing it. Their mundane, even-keeled responses don’t get shuttled to the top of your newsfeed.

From Discomfort to Disinformation.

Social media’s business model tends, by its very nature, to veer from truth. Remember, social media companies make money keeping you glued to your feed. And disinformation is a great way to generate reactions. In fact, a team at MIT set out to measure just how much faster disinformation spreads online. Six times faster, they found.

From a given social media corporation’s perspective, if reactions are what drive attention on social media, then why tether content to the truth at all? Social media companies have had almost no real incentive to monitor their sites for disinformation. So they simply haven’t. Through the 2020 election cycle, Facebook’s policy was to allow campaigns to publish ads without any truth verification whatsoever. Mark Zuckerberg said, “people should be able to judge for themselves the character of politicians.”

To demonstrate the absurdity of this, Elizabeth Warren’s campaign ran intentionally false facebook ads during the 2020 Presidential primary claiming that Mark Zuckerberg was intentionally backing the re-election of Donald Trump. This after the Trump campaign ran false ads about then-candidate Joe Biden.

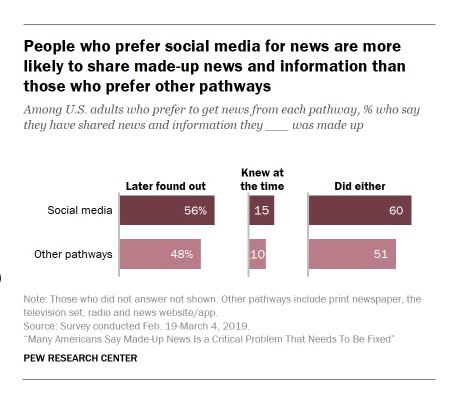

Zuckerberg’s claims demonstrate that he may be the victim of his own selection bias amplification machine. He’s someone who’s feed is probably populated with center-left content and who, by dint of his socioeconomic position probably consumes far more media outside social media that acts as a check on what he might see on his own platform. To him, the lies politicians tell on social media are self-evidently false—a comment on their poor character. But for the folks most likely to get their news on the platform, who may not have the same tools to discern fact from fiction, who’ve been fed the same lies for years—the folks most likely to vote for Trump—his lies become their truth. Facebook’s own algorithm made it so. A Pew Research study found that people who are more likely to get their news on social media are more likely to push disinformation as well. It’s a self-accelerating feedback loop.

Beyond the algorithm, there’s something else about social media that makes it such a cesspool of disinformation: social platforms create a natural space for concentrating all of our misinformation. In their book LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media, Peter Singer and Emerson Booking quote Colonel Robert Bateman: “Once, every village had an idiot. It took the internet to bring them all together.”

Think of the anti-vaxx movement. Thirty years ago an anti-vaccine parent would discover vaccine misinformation individually and maybe share it with their social circle. Today, they can share that misinformation with hundreds of thousands of like-minded, misinformed parents in an echo-chamber—confirming their beliefs through their own selection bias. The anti-vaccine movement, by the way, has been linked to outbreaks of measles, which the United States once eradicated, all across the country.

Disinformation is Deadly.

Americans have suffered the COVID-19 pandemic worse than any other high-income country in the world. Though we account for 4% of the global population, we are 20% of global cases. Why? Because we’ve failed to do even the most basic things to address this pandemic. Intentionally obstructive disinformation campaigns have undermined public trust in basic public health.

Social media disinformation campaigns turned wearing a face mask—the simplest way to protect yourself, your family and your community—into some kind of referendum on our belief in liberty. Simple lockdowns to prevent mass spread were meme-ified into a bold-faced assault on business. Science itself became a public opinion contest—people believing that they could and should force the FDA to approve the use of Hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 by sheer force of Twitter trend, rather than sound scientific testing—which it subsequently failed.

Social media companies have been complicit in the spread of this disinformation on their platforms. The global non-profit organization Avaaz audited medical misinformation on Facebook. They found that by August of 2020, misinformation had accumulated 3.8 billion (with a B!) views on Facebook—and only 16% of that clear misinformation was labeled with a warning. Fact checkers had failed 84% of the time. The misinformation was allowed to stay up.

As we watched armed insurrectionists storm the Capitol on January 6th, many wondered how it could have come to this. To be honest, given my experiences with rightwing online abuse from folks like bootleg Hercules, I’m impressed that we’ve staved this off so long.

Though Donald Trump—a narcissistic former reality TV star—was uniquely suited to exploit social media’s unique capacity to compound and multiply demagoguery, he was aided and abetted by social media platforms the entire way. It’s hard to imagine the idea of a Donald Trump presidency before the internet era.

Facebook, in particular, has emerged as an echo-chamber of the right (and wrong). Throughout the 2020 campaign, for example, the top ten most engaged posts on Facebook were routinely filled by far right personalities like Dan Bongino, Franklin Graham, and Candace Owens. Why? Because rightwing propaganda gets clicks. And clicks sell ads.

Long before that, he learned how to use his @realdonaldtrump Twitter handle to foment conspiracy theories to force Americans to take sides—the truth vs. Trump. Don’t forget his birther conspiracy that President Obama was allegedly born outside the US. All of it exploited the worst characteristics of social media’s business model to foment conflict and build notoriety.

And though, at the bitter end, he was deplatformed by the very platforms that created him, it was, by then, too late. The obvious question being, why did it take so long? Well, it's like the plot of one of those heist movies where one partner in the heist turns on the other just as the cops close in on them both. He was deplatformed the day after the Georgia Senate run-off elections were called for Senators Warnock and Ossoff—with Democrats threatening action on Big Tech. The platforms didn’t do it because it was the right thing to do—but because they knew it was either him or them. Big Tech was playing for a plea bargain. Make no mistake, though, both were in on it the entire time. The damage Donald Trump has done to our politics is immeasurable—but he didn’t do it alone. At each step, he played social media against American democracy. We all lost.

Disarming Disinformation.

If we’re serious about protecting our democracy—and our public health—we need to regulate social media and curb the power Big Tech corporations have been able to acquire over our economy and our public discourse (we need to break them up, too, because they are some of the worst monopolists in the world right now—but that’s a different conversation for a different day).

Relying on social media companies to police themselves—as much as they want us to—clearly doesn’t work. The growing call for some kind of editorial responsibility-taking over the past decade has been met with the anemic responses we’ve seen through the current moment. In fact, after de-platforming Trump, Facebook is now considering whether or not to give him back his account—effectively handing him back the keys to the semi-truck he just crashed into American Democracy.

And sure, all of us should always be thinking about how to improve our internet hygiene so we don’t inadvertently share misinformation (yes, I’ve accidentally done it too). But these kinds of end user campaigns—I’m imagining Nancy Reagan telling us to “just say no” to sharing viral fake news posts—don’t work on a mass scale, either.

We need legislative action that forces social media companies to either rethink their business model or bars them from exploiting tactics that spread disinformation online in pursuing that business model.

Promisingly, social media regulation is a bipartisan issue. It's something both parties agree we should do...but for entirely opposite reasons. So less promisingly, there’s little agreement on what should actually be done.

The GOP thinks that social media should be regulated because it censors free speech on the internet. Indeed, Senator Josh Hawley, who’s actions directly contributed to the Capitol insurrection riots, has a forthcoming book about this called “The Tyranny of Big Tech,” which Simon & Schuster dropped after the riots. It’s since been picked up by Regnery Publishing— joining other titles such as “Civil War 2.0” by Dinesh D’Souza, a Trumpist zealot of ill repute.

Hawley and friends argue that social media moderation, including the harmful disinformation that tends to flourish on the right—or deplatforming a repeat offender like Trump—violates the freedom of speech. Now I’m no first amendment expert, but freedom of speech is one of these concepts that’s afforded a way broader public interpretation than is actually warranted by the law. You can’t scream “fire!” in a crowded theatre—the rush of people to the exits could be deadly. That endangerment through speech isn’t protected. Just like, say, spreading disinformation in the middle of the worst pandemic in over a century.

There’s another point, too. The first amendment protects your freedom of speech from infraction by the state. But social media corporations aren’t the state. These are private companies that don’t owe you a thing. The New York Times doesn’t have a public responsibility to publish whatever you or I send them. Simon & Schuster doesn’t have to publish your book if you’re an neo-fascist insurrectionist (although Josh Hawley thinks they do). And neither Facebook nor Twitter have any obligation to share what we type into the little box.

Now you may argue that no private company should have that much power to shape and censor the public discourse. And with that I’d agree with you. Regardless whether deplatforming Donald Trump, for example, was the right thing to do (and yes, it was the right thing to do), the fact that Twitter had the power to take the favorite megaphone from a sitting President in the first place is rather astounding. But solving that problem is another issue entirely—one of power and monopoly, not one of freedom of speech.

This contention is basically where we find the conversation about one of the principle approaches to regulating social media: repealing Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, the legal statute protecting social media platforms from liability for the material shared on their sites. This became a near obsession for Trump in his last days in office—which is ironic because it seems he doesn’t know how 230 works. Proponents of repealing 230 argue that the legal liability to which social media giants would be exposed would compel far stricter moderation—which of course wouldn’t benefit an arch-disinformer like Trump. But opponents of repealing 230 call it one of the most important tools to protecting free speech on the Internet. Yet as we discussed, private companies are under no obligation to publish anything—and even free speech is necessarily limited when it comes to protecting the public’s health.

Some proposals stop short of completely repealing 230, but seek to limit what it protects. Some propose “carving out” particular categories of online content. For example, in 2018, Trump signed into law a pair of bills known as FOSTA-SESTA (Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act [FOSTA] and Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act [SESTA]) that carved out a Section 230 exception for civil and criminal charges of sex trafficking or facilitating prostitution—now making social media companies liable for this kind of content. Future legislation could expand these kinds of carve outs to other types of content. One bipartisan proposal that’s gotten a fair bit of attention from Senators Brian Schatz and John Thune is the PACT Act, which would repeal 230 protections for content deemed illegal by a court, force platforms to specify their process for identifying and eliminating prohibited content, empower federal and state enforcement agencies, force them to be very clear about their terms of service and enforce them, and be transparent about their moderation.

Section 230-based regulations strike at the heart of the disincentive that these companies have to moderate disinformation by making them liable for it. Another approach might be to regulate the tactics internet companies can use on their platforms. Bot amplification and algorithmic sorting are two obvious places to start. Though regulating tactics like these wouldn’t force social media corporations to take disinformation off their sites, they could go a long way in reducing how fast and far they spread. They’d make our social media environment a little bit more like our real environment rather than amplifying only the most provocative material that polarizes our worldviews. They also side-step the dubious, bad-faith free speech arguments. After all, even if an expansive interpretation of the first amendment might justify you saying what you want on a private platform, it doesn’t entitle you to a microphone in the form of millions of fake accounts that echo it for you. We regulate sale of certain products in the name of the public welfare all the time. In that view, corporations shouldn’t be able to create spaces that look like the information-equivalent of a hall of mirrors, taking your ideas and throwing them back at you in warped ways to get a reaction—all to sell you something.

Will it happen? My guess is that social media reform is, in fact, on the horizon. When coupled with antitrust policies to curb the monopoly power of major tech industry players, I think it will open the door to a flurry of new platforms in the coming few years. In the past two weeks alone, I’ve joined two new social media platforms—Telepath and Clubhouse—each trying to offer a user experience that solves for the worst things about larger competitors like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. But the advent of Parler and Gab catering directly to the online right specifically trying to escape moderation along with the massive swing of users to encrypted texting platforms like Telegram suggests that we’re likely going to see polarization by platform. Rather than disinformation making the rounds on a few large platforms everyone uses, we’re probably going to see people who want to consume and share that kind of thing escaping to platforms that resist any effort to moderate it.

That may, in fact, be a good thing. There’s good evidence to suggest that disinformation and algorithmic sorting suck users into the abyss—so decanting the most aggressive disinformers into their own networks may insulate those who are susceptible from the poison.

Alright, now that that’s through—mind giving this a share? I know, I know. But seriously, will you?