by Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian, Christelle Langley, Emmanuel A Stamatakis, and Lennart Spindler, The Conversation

August 15, 2021

in Cognitive Science

Consciousness is arguably the most important scientific topic there is. Without consciousness, there would after all be no science. But while we all know what it is like to be conscious – meaning that we have personal awareness and respond to the world around us – it has turned out to be near impossible to explain exactly how it arises from the hardware of the brain. This is dubbed the “hard” problem of consciousness.

Solving the hard problem is a matter of great scientific curiosity. But so far, we haven’t even solved the “easy” problems of explaining which brain systems give rise to conscious experiences in general – in humans or other animals. This is of huge clinical importance. Disorders of consciousness are a common consequence of severe brain injury and include comas and vegetative states. And we all experience temporary loss of awareness when under anaesthesia during an operation.

In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, we have now shown that conscious brain activity seems to be linked to the brain’s “pleasure chemical”, dopamine.

The fact that the neural mechanisms that underpin consciousness disorders are difficult to characterise makes these conditions hard to diagnose and treat. Brain-imaging has established that a network of interconnected brain regions, known as the default mode network, is involved in self-awareness. This network has also been shown to be impaired in anaesthesia and after brain damage that causes disorders of consciousness. Importantly, it seems to be crucial to conscious experience.

Some patients, however, may seem to be unconscious when they in fact are not. In a landmark study in 2006, a team of researchers showed that a 23-year old woman, who suffered severe brain trauma and was thought to be in a vegetative state following a traffic accident, had signs of awareness. The patient was asked to imagine playing tennis during a brain scan (fMRI)) and the scientists saw that regions of the brain involved in motor processes activated in response.

Similarly, when she was asked to imagine walking through the rooms of her home, regions of the brain involved in spatial navigation, such as the posterior parietal cortex, became active. The pattern of activation that she showed was similar to that of healthy people, and she was deemed to have awareness even though that wasn’t noticeable in classical clinical assessment (not involving brain scans).

Other research has found similar effects in other vegetative state patients. This year, a group of scientists, writing in the journal Brain, warned that one in five patients in vegetative states may in fact be conscious enough to follow commands during brain scans – though there is no consensus on this.

The brain chemical involved in consciousness

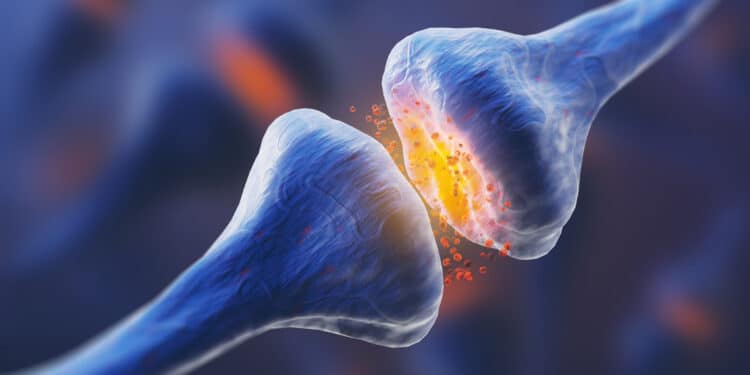

So how do we help these people? The brain is more than just a congregation of different areas. Brain cells also rely on a number of chemicals to communicate with other cells – enabling a number of brain functions. Before our study, there was already some evidence that dopamine, well known for its role in reward, also plays a role in disorders of consciousness.

For example, one study showed that dopamine release in the brain is impaired in minimally conscious patients. Moreover, a number of small-scale studies have shown that patients’ consciousness can improve by giving them drugs that act through dopamine.

The dopamine source in the brain is called the ventral tegmental area (VTA). It is from this region that dopamine is released to most areas in the cortex. In our recent study, we showed that the function of this source of the brain’s dopamine is impaired in patients with disorders of consciousness and also in healthy people after the administration of an anaesthetic.

In healthy people, we found that VTA function was restored after withdrawal of sedation. And people with reduced consciousness who improved over time also regained some of their VTA function. In addition, the dysfunction in dopamine was linked with a dysfunction in the default mode network, which we already know is key in consciousness. This suggests that dopamine may really have a central role in maintaining our consciousness.

The study, carried out in the Division of Anaesthesia at the University of Cambridge, also shows that the use of current and future drugs, which act on dopamine, should help improve our understanding of anaesthesia. Surprisingly, although anaesthesia with ether was first used in surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1846, the specific processes as to how general anaesthetics act at multiple sites to produce anaesthetic action remain a mystery.

But the most exciting aspect of this research is ultimately that it gives hope for better treatments of consciousness disorders, using drugs that act on dopamine.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.