The country’s health minister says deportation flights are driving up coronavirus cases after a flight had 75% test positive

THE GUARDIAN Staff and agencies in Guatemala City Wed 15 Apr 2020

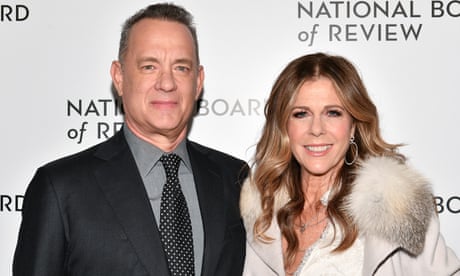

An immigration official in Guatemala oversees the arrival of migrants deported from the US. Photograph: Johan Ordóñez/AFP via Getty Images

US deportation flights to Guatemala are driving up the country’s Covid-19 caseload, according to the country’s health minister, who said that on one flight about 75% of the deportees tested positive for the virus.

Hugo Monroy said that the United States had become the “Wuhan of the Americas” referring to the Chinese province where the pandemic began.

“We must not stigmatize, but I have to speak clearly. The arrival of deportees who have tested positive has really increased the number of [coronavirus] cases,” he said on Tuesday.

US migrant deportations risk spreading coronavirus to Central America

“There are really flights where the deportees arrive … with fever – and they get on the planes that way,” said Monroy on Tuesday. “We automatically evaluate them here and test them and many of them have come back positive.”

Later, the presidential spokesman, Carlos Sandoval, told reporters that Monroy was referring to a March flight on which “between 50% and 75% [of the passengers] during all their time in isolation and quarantine have come back positive”.

Before Tuesday, Guatemala had reported only three positive infections among deportees flown back by the United States.

Joaquín Samayoa, spokesman for the foreign affairs ministry, confirmed a fourth positive case for a migrant who arrived on a flight on Monday. At least three of the migrants who arrived Monday were taken directly to a hospital for Covid-19 testing.

It remained unclear why before Tuesday the government had only reported three deportees who tested positive and how many more would have been among the high percentage who tested positive onboard that March flight.

Guatemala again began receiving deportation flights from the United States on Monday after a one-week pause prompted by three deportees testing positive for Covid-19.

The Guatemalan government had asked the United States to not send more than 25 deportees per flight, to give them health examinations before departure and to certify that they were not infected.

However, the flights resumed on Monday with 76 migrants onboard the first and 106 on the second. Guatemala’s foreign ministry did not immediately clarify why the US had not complied with its requirements, but the flights came on the same day that the US state department announced that aid would continue to Guatemala and the other Northern Triangle countries.

One of Monday’s flights also included 16 unaccompanied minors, according to the Guatemalan Immigration Institute.

Since January, the US has deported nearly 12,000 Guatemalans, including more than 1,200 children.

US deportation flights to Guatemala are driving up the country’s Covid-19 caseload, according to the country’s health minister, who said that on one flight about 75% of the deportees tested positive for the virus.

Hugo Monroy said that the United States had become the “Wuhan of the Americas” referring to the Chinese province where the pandemic began.

“We must not stigmatize, but I have to speak clearly. The arrival of deportees who have tested positive has really increased the number of [coronavirus] cases,” he said on Tuesday.

US migrant deportations risk spreading coronavirus to Central America

“There are really flights where the deportees arrive … with fever – and they get on the planes that way,” said Monroy on Tuesday. “We automatically evaluate them here and test them and many of them have come back positive.”

Later, the presidential spokesman, Carlos Sandoval, told reporters that Monroy was referring to a March flight on which “between 50% and 75% [of the passengers] during all their time in isolation and quarantine have come back positive”.

Before Tuesday, Guatemala had reported only three positive infections among deportees flown back by the United States.

Joaquín Samayoa, spokesman for the foreign affairs ministry, confirmed a fourth positive case for a migrant who arrived on a flight on Monday. At least three of the migrants who arrived Monday were taken directly to a hospital for Covid-19 testing.

It remained unclear why before Tuesday the government had only reported three deportees who tested positive and how many more would have been among the high percentage who tested positive onboard that March flight.

Guatemala again began receiving deportation flights from the United States on Monday after a one-week pause prompted by three deportees testing positive for Covid-19.

The Guatemalan government had asked the United States to not send more than 25 deportees per flight, to give them health examinations before departure and to certify that they were not infected.

However, the flights resumed on Monday with 76 migrants onboard the first and 106 on the second. Guatemala’s foreign ministry did not immediately clarify why the US had not complied with its requirements, but the flights came on the same day that the US state department announced that aid would continue to Guatemala and the other Northern Triangle countries.

One of Monday’s flights also included 16 unaccompanied minors, according to the Guatemalan Immigration Institute.

Since January, the US has deported nearly 12,000 Guatemalans, including more than 1,200 children.