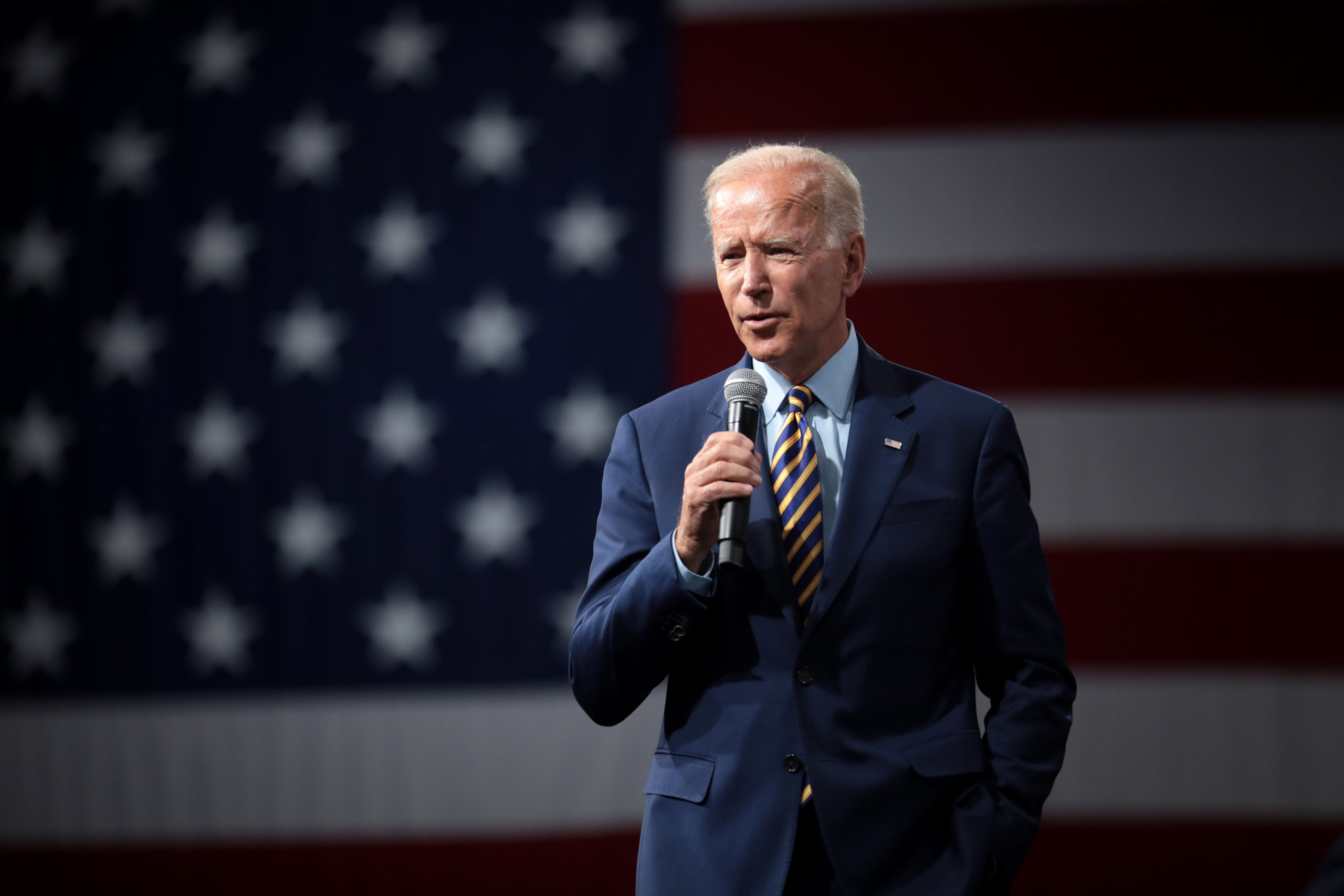

The Biden Administration Just Broke International Law.

Why Doesn’t Anyone Care?

Joe Biden just authorised airstrikes on Syria without congressional approval.

by Aaron Bastani

5 March 2021

In January 2020, Iran’s most powerful general Qassem Soleimani was killed in a US airstrike along with four members of Iraq’s Popular Mobilisation Forces. Authorised by Donald Trump, the attack took place near Baghdad International Airport, with the US claiming Soleimani was in Iraq to coordinate attacks on US diplomatic and military personnel. Soon afterwards, however, Iraq’s prime minister disclosed that the major general was in fact delivering Iran’s response to a letter Iraq had despatched on behalf of Saudi Arabia.

At the time, leading Democrats criticised Trump for authorising the strike. Joe Biden accused the president of having “tossed a stick of dynamite into a tinderbox”, leaving the region “on the brink of a major conflict”. Elizabeth Warren, meanwhile, said Trump risked escalating tensions with Iran, while Pete Buttigieg declared there were “serious questions about how this decision was made”. Nancy Pelosi echoed such sentiments, saying the president was wrong to authorise the attack without first consulting Congress.

Yet last week, after president Biden approved his first military action, leading Democrats appeared by and large unconcerned. This is especially notable given that Biden, like Trump, authorised the action without congressional approval.

What was the Biden administration’s motivation here? Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby claimed the strikes, which were aimed at “infrastructure utilised by Iranian-backed militant groups in eastern Syria” in response to attacks against US and coalition personnel in Iraq, were intended to punish the militias – but not escalate tensions with Iran. A separate official attempted to justify the action by claiming it may have killed only a “handful” of people, while the targeted “compound” was also, according to the US, previously used by Isis.

Independent sources, however, now put the death toll from the strike at at least 22. Moreover, given those militias now subject to US bombing helped defeat Isis, a perennial question re-emerges: whose side is the US on in Syria? And what does it actually want from its westernmost ‘forever war’ in Asia?

Questionable grounds are accompanied by dubious legality, with the White House claiming the strikes were an act of “self defence”. In so doing, it cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which states nothing “shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations.”

But what they neglected to mention were the words that come after this: “…until the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security”. Given the attack wasn’t on American soil – and the US had adequate time to work with the Security Council to punish Iran through diplomacy – the attacks had no legal basis. “They are citing the correct sources of law,” a leading scholar in the field told Vox, but “are wildly misinterpreting them.”

What’s more, if Iran is the target of Washington’s ire, then what is the basis for strikes in a neighbouring state? Assad is a brutal dictator. But Syria is a sovereign country.

Before you call me an apologist for the Syrian president, these were in fact the words of Jen Psaki in 2017 after Trump authorised a similar attack without congressional approval, when Psaki was a political contributor for CNN. In her new job as White House press secretary, however, she doesn’t pose such questions, but rather deflects them. Such hypocrisy also applies to vice president Kamala Harris, who tweeted in 2018 that she was “deeply concerned about the legal rationale” for strikes in Syria. Similar comments in recent days, unsurprisingly, have not been forthcoming.

Even more galling than the double standard from senior Democrats – from Psaki and Harris to Pelosi and Buttigieg – is how behaviour reminiscent of Trump is actually celebrated by some of his biggest critics. “So different having military action under Biden,” tweeted Amy Suskind, who worked on Wall Street for two decades before rising to prominence opposing the former president. “No middle school level threats on Twitter”. One reply to that tweet read: “Such a quiet attack. No drama, no TV coverage of bombs hitting targets…what a difference!” This was in response to seven 500-pound bombs and significant loss of life.

The idea that US drone strikes in Syria constitute “self-defence” would be funny were it not so serious. The strikes were undertaken, after all, in response to events in Iraq – a country whose elected government requested the withdrawal of US forces a year ago. There is a term for when a foreign power remains in a country despite being asked to leave by its legitimate government: it’s a military occupation. Appeals to “self-defence” are doubly strange when one considers that the city of Erbil is 6,000 miles away from Washington, while Iran, which has denied any involvement in the attack, shares a land and sea border with 11 countries that are home to US military bases.

Despite having denied involvement in the Erbil attack, Kata’ib Hezbollah, one of the groups targeted, was allied with the US air force in 2015 during the capture of Tikrit. As with Soleimani, their reward for helping neutralise the world’s most dangerous terrorist organisation was for the US to then turn on them. As late as last year, the Washington Post described the organisation as “part of Iraq’s conventional security forces since helping Iraqi and coalition forces defeat the Islamic State”. Six months on, they are a foe whose deaths are an afterthought.

Rather than self-defence, the truth is that the targeting of militias in Syria – in response to events in Iraq – was done to avoid inflaming a volatile situation in the latter, with the US military already asked to leave. As with the execution of Soleimani, the Pentagon would not disclose the threat US forces faced in either country, saying instead the attack was to deter future Iranian assaults on Americans – although not a single Iranian national was among the 22 dead in Syria. Last week showed that for Biden, like Trump, making a political statement matters more than any loss of life or international law.

Murdering people in the name of ‘deterrence’ isn’t just immoral, but illegal too – and if those who criticised Donald Trump as commander-in-chief wish to enjoy a shred of credibility, they should say as much. As one tweet put it: “We got an airstrike before we got a stimulus check.” Continuing America’s forever wars isn’t just ethically disastrous – it may also allow a Republican back into the White House in 2024.

Aaron Bastani is a Novara Media contributing editor and co-founder.