Ancient ‘smellscapes’ are wafting out of artifacts and old texts

ID’ing odor molecules and brewing Cleopatra’s perfume are part of new research on past scents

The spectrum of smells in ancient societies, and their possible cultural meanings, are being explored by scientists who study odor molecules, old documents and other archaeological finds. Here, a carved relief of an ancient Egyptian queen smelling a lotus flower represents the fragrant world that pharaohs and their families inhabited.

ALAIN GUILLEUX/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

By Bruce BowerScience News

LONG READ

Ramses VI faced a smelly challenge when he became Egypt’s king in 1145 B.C. The new pharaoh’s first job was to rid the land of the stench of fish and birds, denizens of the Nile Delta’s fetid swamps.

That, at any rate, was the instruction in a hymn written to Ramses VI upon his ascension to the throne. Some smells, it seems, were considered far worse than others in the land of the pharaohs.

Surviving written accounts indicate that, perhaps unsurprisingly, residents of ancient Egyptian cities encountered a wide array of nice and nasty odors. Depending on the neighborhood, citizens inhaled smells of sweat, disease, cooking meat, incense, trees and flowers. Egypt’s hot weather heightened demand for perfumed oils and ointments that cloaked bodies in pleasant smells.

“The written sources demonstrate that ancient Egyptians lived in a rich olfactory world,” says Egyptologist Dora Goldsmith of Freie Universität Berlin. A full grasp of ancient Egyptian culture requires a comprehensive examination of how pharaohs and their subjects made sense of their lives through smell, she contends. No such study has been conducted.

Archaeologists have traditionally studied visible objects. Investigations have reconstructed what ancient buildings looked like based on excavated remains and determined how people lived by analyzing their tools, personal ornaments and other tangible finds.

Rare projects have re-created what people may have heard thousands of years ago at sites such as Stonehenge (SN: 8/31/20). Piecing together, much less re-creating, the olfactory landscapes, or smellscapes, of long-ago places has attracted even less scholarly curiosity. Ancient cities in Egypt and elsewhere have been presented as “colorful and monumental, but odorless and sterile,” Goldsmith says.

Changes are in the air, though. Some archaeologists are sniffing out odor molecules from artifacts found at dig sites and held in museums. Others are poring over ancient texts for references to perfume recipes, and have even cooked up a scent much like one presumably favored by Cleopatra. In studying and reviving scents of the past, these researchers aim to understand how ancient people experienced, and interpreted, their worlds through smell.

Molecular odors

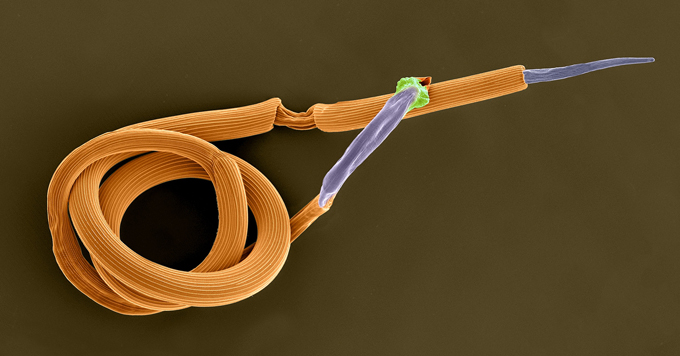

A growing array of biomolecular techniques is enabling the identification of molecules from ancient aromatic substances preserved in cooking pots and other containers, in debris from city garbage pits, in tartar caked on human teeth and even in mummified remains.

Take the humble incense burner, for instance. Finding an ancient incense burner indicates only that a substance of some kind was burned. Unraveling the molecular makeup of residue clinging to such a find “can determine what exactly was burned and reconstruct whether it was the scent of frankincense, myrrh, scented woods or blends of different aromatics,” says archaeologist Barbara Huber.

That sort of detective work is exactly what Huber, of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, and her colleagues did in research on the walled oasis settlement of Tayma in what’s now Saudi Arabia.

Researchers generally assume that Tayma was a pit stop on an ancient network of trade routes, known as the Incense Route, that carried frankincense and myrrh from southern Arabia to Mediterranean destinations around 2,300 to 1,900 years ago. Frankincense and myrrh are both spicy-smelling resins extracted from shrubs and trees that grow on the Arabian Peninsula and in northeastern Africa and India. But Tayma was more than just a refueling oasis for trade caravans.

The desert outpost’s residents purchased aromatic plants for their own uses during much of the settlement’s history, a team led by Huber found. Chemical and molecular analyses of charred resins identified frankincense in cube-shaped incense burners previously unearthed in Tayma’s residential quarter, myrrh in cone-shaped incense burners that had been placed in graves outside the town wall, and an aromatic substance from Mediterranean mastic trees in small goblets used as incense burners in a large public building.

Fragrances of various kinds that must have had special meanings permeated a range of daily activities at ancient Tayma, Huber’s group reported in 2018 in Munich at the 11th International Conference on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East.

In a more recent study, published March 28 in Nature Human Behavior, Huber and her colleagues outlined ways to detect chemical and genetic traces of ancient scents.

Incense burners found at an Arabian Peninsula settlement called Tayma, represented by this cone-shaped artifact, contain clues to a range of fragrances used in daily activities roughly 2,000 years ago.A.D. RIDDLE/BIBLEPLACES.COM

Other researchers have gone searching for molecular scent clues in previously excavated pottery. Analytical chemist Jacopo La Nasa of the University of Pisa in Italy and his colleagues used a portable version of a mass spectrometer to study 46 vessels, jars, cups and lumps of organic material.

These artifacts were found more than a century ago in the underground tomb of Kha and his wife Merit, prominent nonroyals who lived during Egypt’s 18th dynasty from about 1450 B.C. to 1400 B.C. The spectrometer can detect the signature chemical makeup of invisible gases emitted during the decay of different fragrant plants and other substances that had been placed inside vessels.

Analyses of residue from inside seven open vessels and of one lump of unidentified organic material detected oil or fat, beeswax or both, the scientists report in the May Journal of Archaeological Science. One open vessel yielded possible chemical markers of dried fish and of a possible aromatic resin that could not be specified. The remaining containers were sealed and had to stay that way due to museum policy. Measurements taken in the necks of those vessels also picked up signs of oils or fats and beeswax in some cases. Evidence of a barley flour appeared in one vessel’s neck.

Museum-based studies such as La Nasa’s have great potential to unlock ancient scents. But that’s true only if researchers can open sealed vessels and, with a bit of luck, find enough surviving chemical components of whatever was inside to identify the substance, Goldsmith says.

Luck did not favor La Nasa’s group, she says. “Their analyses did not detect any [specific] scents.”

Oils, fats and beeswax in the seven open vessels could only have constituted neutral-smelling base ingredients for ancient Egyptian perfumes and ointments, Goldsmith says. Starting with mixtures of those substances, Egyptian perfume makers added a host of fragrant ingredients that included myrrh, resin and bark from styrax and pine trees, juniper berries, frankincense and nut grass. The heating of these concoctions produced strongly scented ointments.

Re-creating Cleopatra’s perfume

A tradition of fragrant remedies and perfumes began as the first Egyptian royal dynasties assumed power around 5,100 years ago, Goldsmith’s research suggests. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic and cursive documents describe recipes for several perfumes. But precise ingredients and preparation methods remain unknown.

That didn’t stop Goldsmith and historian of Greco-Roman philosophy and science Sean Coughlin of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague from trying to re-create a celebrated Egyptian fragrance known as the Mendesian perfume. Cleopatra, a perfume devotee during her reign as queen from 51 B.C. to 30 B.C., may have doused herself with this scented potion. The perfume took its name from the city where it was made, Mendes.

Excavations conducted since 2009 at Thmouis, a city founded as an extension of Mendes, have uncovered the roughly 2,300-year-old remains of what was probably a fragrance factory, including kilns and clay perfume containers (SN: 11/27/19). Archaeologist Robert Littman of the University of Hawaii at Manoa and anthropological archaeologist Jay Silverstein of the University of Tyumen in Russia, who direct the Thmouis dig, asked Goldsmith and Coughlin to try to crack the Mendesian perfume code by consulting ancient writings.

After experimenting with ingredients that included desert date oil, myrrh, cinnamon and pine resin, Goldsmith and Coughlin produced a scent that they suspect approximates what Cleopatra probably wore. It’s a strong but pleasant, long-lasting blend of spiciness and sweetness, they say.

Ingredients of a re-creation of an ancient fragrance called the Mendesian perfume consist of pine resin, cinnamon cassia, true cinnamon, myrrh and moringa oil (shown from left to right). Cleopatra herself may have worn the ancient scent.

Ingredients of a re-creation of an ancient fragrance called the Mendesian perfume consist of pine resin, cinnamon cassia, true cinnamon, myrrh and moringa oil (shown from left to right). Cleopatra herself may have worn the ancient scent.D. GOLDSMITH AND S. COUGHLIN

A description of the Thmouis discoveries and efforts to revive the Mendesian scent — dubbed Eau de Cleopatra by the researchers — appeared in the Sept. 2021 Near Eastern Archaeology.

Goldsmith has re-created several more ancient Egyptian perfumes from written recipes for fragrances that were used in everyday life, for temple rituals and in the mummification process.

Ancient smellscapes

Odor molecules unearthed in archaeological digs and reconstituted perfumes from the past, however, offer only a partial view of the scents of thousands of years ago. To get a more complete picture of an ancient city’s or town’s range of smells — its smellscape — some archaeologists are combing ancient written texts for references to smell.

That’s what Goldsmith did to come up with what she thinks is a smellscape typical of ancient Egyptian cities. Here’s what a “smellwalk” through one of these cities would entail, she says.

In the royal palace, for instance, the perfumed smell of rulers and their family members would have overpowered that of court officials and servants. That would perhaps have denoted special ties to the gods among those in charge, Goldsmith wrote in a chapter of The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East, published in September of 2021.

Smells of aromatic substances ignited in incense burners (such as the one held here by the pharaoh Ramses II in a temple wall carving at the Karnak Temple Complex near Luxor, Egypt) held deep meaning for ancient Egyptians, researchers say.

PRISMA ARCHIVO/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

In temples, priests anointed images of gods with what was called the 10 sacred oils. Though their ingredients are mostly unknown, each substance apparently had its own pleasing scent and ritual function. Temples mixed smells of perfumes, flowers and incense with roasted meat. Written sources describe the smell of fatty meat being grilled as especially pleasing and a sign of peace as well as authority over enemies.

In other parts of an ancient Egyptian city, Goldsmith says, scribal students lived in a special building where they learned Egyptian script. Achieving such knowledge required total devotion and the avoidance of perfume or other pleasant scents. One ancient source described aspiring scribes as “stinking bulls.” That name speaks, and reeks, for itself.

Meanwhile, in workshops, sandal-makers mixing tan to soften hides and smiths making metal weapons at the mouths of furnaces probably developed their own distinctive, foul smells, Goldsmith says.

Stinky odors get far fewer mentions than sweet aromas in many of the written accounts from ancient Egypt that Goldsmith reviewed. Goats and other domestic animals, butchered carcasses, open latrines and garbage in the streets, for example, get no mention in these surviving texts.

An awareness that such texts may represent only an elite perspective — and thus not reveal the entire smellscape of the time or how it was perceived by everyday folks — is crucial when compiling the scents of ancient history, Goldsmith says.

Cultured noses

Once researchers come up with a reasonable reconstruction of an ancient city’s smellscape, the challenge shifts to figuring out how the ancients interpreted those smells.

Scent is a powerful part of the human experience. Today, scientists know that smells, which humans might discriminate surprisingly well, can instantly trigger memories of past experiences (SN: 3/20/14). And social and ritual meanings also get attached to specific odors — there’s nothing like the smell of freshly mown grass and grilled hot dogs to evoke memories of summer days at the ballpark.

People in modern settings probably perceive the same smells as nice or nasty as folks in ancient Egypt or other past societies did, says psychologist Asifa Majid of the University of Oxford. In line with that possibility, members of nine non-Western cultures, including hunter-gatherers in Thailand and farming villagers in highland Ecuador, closely agreed with Western city dwellers when ranking the pleasantness of 10 odors, Majid and her colleagues report April 4 in Current Biology.

Smells of vanilla, citrus and floral sweetness — dispensed by pen-sized devices — got high marks. Odors of rancid oiliness and a fermented scent like that of ripe cheese or human sweat evoked frequent “yech” responses.

A collective “yech” in response to the Nile Delta’s moist, stinky emissions may have inspired the hymn that instructed Ramses VI to rid the land of its swampy fish and fowl smell. But Goldsmith argues that the hymn’s meaning is deeper and hinges on what ancient Egyptians saw as a conflict between sweet and evil smells.

In a 2019 review of texts written during the reigns of various ancient Egyptian kings, Goldsmith was struck by frequent references to this odiferous opposition. She concluded that ancient Egyptians’ largely unexplored views about what exemplified good and bad smells could provide insights into their world view. Researchers have long noted that concepts known as isfet and ma’at helped ancient Egyptians determine what was good or bad in the world. Isfet referred to a natural state of chaos and evil. Ma’at denoted a world of order and justice.

Signature odors were associated with isfet and ma’at, Goldsmith proposed in a chapter in Sounding Sensory Profiles in the Ancient Near East. In Nile societies, the smelly fish and birds best represented isfet’s nasal assault. Fish, in particular, signified not only stench but also the danger of unfamiliar places outside the pharaoh’s command, she concludes. Meanwhile, the ancient documents equated scented ointments and perfumes with the ma’at of civilized, pharaoh-ruled cities, she says.

Thus, an Egyptian pharaoh’s first duty was to erase the social and physical stink of isfet and institute the sweet smell of ma’at, Goldsmith contends. In his welcoming hymn, Ramses VI got a friendly reminder to make Egypt politically strong and olfactorily fresh.

Explicit beliefs connecting isfet with evil smells and ma’at with sweet smells throughout ancient Egyptian history haven’t yet been established but deserve closer scrutiny, says UCLA Egyptologist Robyn Price.

Price thinks that, rather than being fixed, values that were applied to scents fluctuated over time. For instance, some ancient texts describe the “marsh,” where fish and fowl flourished, as a place of divine creation, she says. And documents from southern Egypt often spoke negatively about northern Egyptians, perhaps influencing claims that northern marshes stunk of isfet during periods when the two regions were under separate rule.

So, even if the ancients tagged the same odors as pleasurable or offensive as people do today, culture and context probably profoundly shaped responses to those smells.

Working-class Romans living in Pompeii around 2,000 years ago — before Mount Vesuvius’ catastrophic eruption in A.D. 79 — provide one example. Archaeological evidence and written sources indicate that patrons of small taverns throughout the city were bombarded with strong smells, says archaeologist Erica Rowan of Royal Holloway, University of London. Diners standing or sitting in small rooms and at outdoor counters whiffed smoky, greasy food being cooked, body odors of other customers who had been toiling all day and pungent aromas wafting out of nearby latrines.

The smells and noises that filled Pompeii’s taverns provided a familiar and comforting experience for everyday Romans, who made these establishments successful, Rowan suspects. Excavations have uncovered 158 of these informal eating and drinking spots throughout Pompeii.

Pompeii residents eating at small taverns such as this one around 2,000 years ago may have whiffed a range of nice and nasty odors that the residents experienced as familiar and comforting.

AP PHOTO/GREGORIO BORGIA

Roman cities generally smelled of human waste, decaying animal carcasses, garbage, smoke, incense, cooked meat and boiled cabbage, Classical historian Neville Morley of the University of Exeter in England wrote in 2014 in a chapter of Smell and the Ancient Senses. That potent mix “must have been the smell of home to its inhabitants and perhaps even the smell of civilization,” he concluded.

Ramses VI undoubtedly regarded the perfumed world of his palace as the epitome of civilized life. But at the end of a long day, Egyptian sandal-makers and smiths, like Pompeii’s working stiffs, may well have smelled home as the air of city streets filled their nostrils.

Questions or comments on this article? E-mail us at feedback@sciencenews.org

Editor's Note:

This story was updated May 4, 2022, to note Asifa Majid's new affiliation with the University of Oxford.

A version of this article appears in the June 18, 2022 issue of Science News.

CITATIONS

D. Goldsmith. Smellscapes in ancient Egypt. In K. Neumann and A. Thomason, eds., The Routledge Handbook of the Senses in the Ancient Near East. New York, September 2021.

J. La Nasa et al. Archaeology of the invisible: The scent of Kha and Merit. Journal of Archaeological Science. Vol. 141, May 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2022.105577.

A. Arshamian et al. The perception of odor pleasantness is shared across cultures. Current Biology. Published April 4, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.062.

B. Huber et al. How to use modern science to reconstruct ancient scents. Nature Human Behavior. Published March 28, 2022. doi: 10.1038/s41562-022-01325-7.

R.J. Littman et al. Eau de Cleopatra: Mendesian perfume and Tell Timai. Near Eastern Archaeology. Vol. 84, September 2021, p. 216. doi: 10.1086/715345.

E. Rowan. The sensory experiences of food consumption. In R. Skeates and J. Day, eds., The Routledge Handbook of Sensory Archaeology. New York, November 2019.

D. Goldsmith. Fish, fowl and stench in ancient Egypt. In A. Schellenberg and T. Krüger, eds., Sounding Sensory Profiles in the Ancient Near East. SBL Press, 2019.

B. Huber et al. An archaeology of odors: Chemical evidence of ancient aromatics at the oasis of Tayma, NW Arabia. 11th International Conference on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Munich, April 3–7, 2018.

N. Morley. Urban smells and Roman noses. In M. Bradley, ed., Smell and the Ancient Senses. New York, December 2014.

Ingredients of a re-creation of an ancient fragrance called the Mendesian perfume consist of pine resin, cinnamon cassia, true cinnamon, myrrh and moringa oil (shown from left to right). Cleopatra herself may have worn the ancient scent.

Ingredients of a re-creation of an ancient fragrance called the Mendesian perfume consist of pine resin, cinnamon cassia, true cinnamon, myrrh and moringa oil (shown from left to right). Cleopatra herself may have worn the ancient scent.

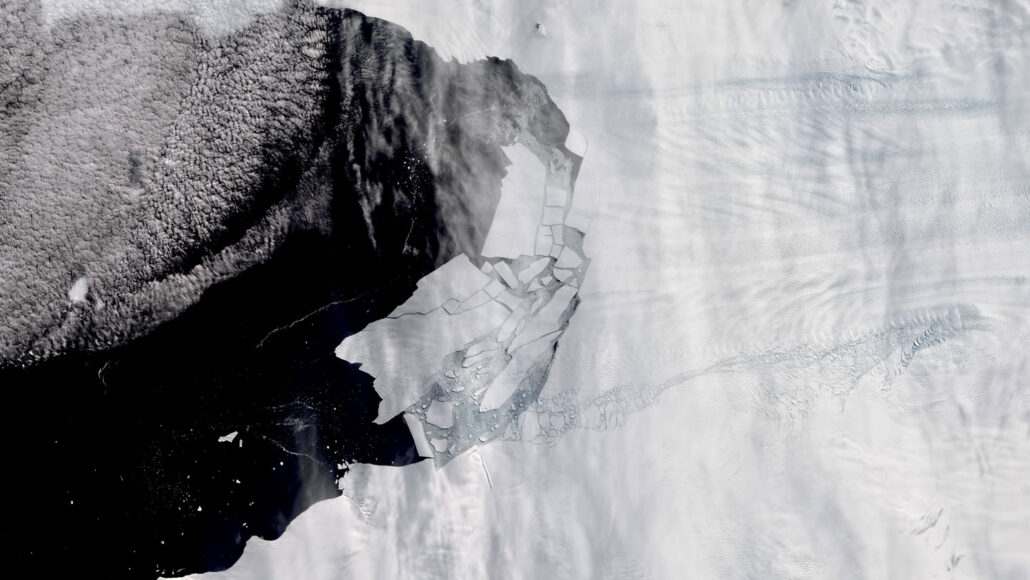

Researchers dated ancient shorelines (seen here as the series of small ridges in the rocky terrain between the foreground boulders and background snow) on islands roughly 100 kilometers from Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in Antarctica to help figure out if the glaciers are in the process of unstable, runaway retreat.

Researchers dated ancient shorelines (seen here as the series of small ridges in the rocky terrain between the foreground boulders and background snow) on islands roughly 100 kilometers from Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in Antarctica to help figure out if the glaciers are in the process of unstable, runaway retreat.