WASHINGTON DC (Kurdistan 24) – Following the US assassination of ISIS’s latest leader in a pre-dawn raid in Syria on Feb. 3, the White House issued a statement later that morning in the name of President Joe Biden, announcing that US forces had killed him.

“We have taken off the battlefield Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi,” it said, ponderously citing three Arabic names.

The latter two names—Hashimi and Qurayshi—are significant. They resonate in the history of Islam and have much meaning for pious Muslims.

The Prophet Mohammed came from the Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe. No figure is more revered among Muslims, while a caliph properly comes from the family of the Prophet.

Yet neither of those two names are in the name of the dead ISIS leader. Rather, they are part of an alias that he adopted, meant to elevate his status among Muslims.

So why should US officials use an alias that ISIS invented? Doesn’t that reinforce ISIS’s narrative: a) this is a struggle about religion and b) ISIS’s goal is to promote a purer form of Islam?

There is an alternative explanation for ISIS’s violence. It is more credible, more informed, and better: this violence is, at its core, a struggle over power and resources. Islam is used as a cover and recruiting device for what is essentially a political conflict.

There is, however, a “stifling group-think to the contrary,” as Col. Norvell De Atkine (US Army, Retired), who long taught Middle Eastern political-military affairs to Special Forces at Fort Bragg, complained to Kurdistan 24.

“People don’t consider the possibility that a lot of what we call ‘Islamic’ terrorism is really about things like power, status, resources,” he said.

“Of course, I wouldn’t know, if they just don’t understand so much about the Middle East, or if they’re going along with the conventional wisdom, because that’s easiest, promotes their careers, etc.,” De Atkine continued. “Or, maybe, it’s some of both.”

The US has Two Different Ways of Dealing with Domestic and “Islamic” Terrorism

The US deals with domestic terrorism—which it generally understands—quite differently from Middle Eastern terrorism, which it does not.

The real name of the deceased ISIS leader was Amir Mohammed Sa’id Abd al-Rahman al-Mawla—as the US officially started in 2019, when it offered a $5 million reward for information about him.

Amir was his given name. He was the son of Mohammed, grandson of Sa’id, great-grandson of Abd al-Rahman, from the Mawla tribe.

Following a domestic attack, US officials make a conscious effort to avoid glamorizing those responsible. Thus, following a shooting in 2019 that killed 12 people in Virginia, authorities, quite deliberately, avoided mentioning the shooter’s name, as The New York Times explained in a report titled, “‘I Will Not Say His Name’: Police Try to End Notoriety of Gunmen on Mass Shootings.”

The idea is to avoid creating a hero for disturbed and violent individuals, who might imitate him, thinking they could also achieve a twisted kind of glory.

When it comes to “Islamic” terrorism, however, the US—officials, as well as media—do the reverse. They embrace the terrorists’ narrative and glamorize key figures.

Mawla’s name is very ordinary. Nothing suggests a special status in Islam—including a family link to the religion’s most revered figure. To use the Qurayshi/Hashimi alias to describe him is to buy into ISIS’ narrative.

What is ISIS?

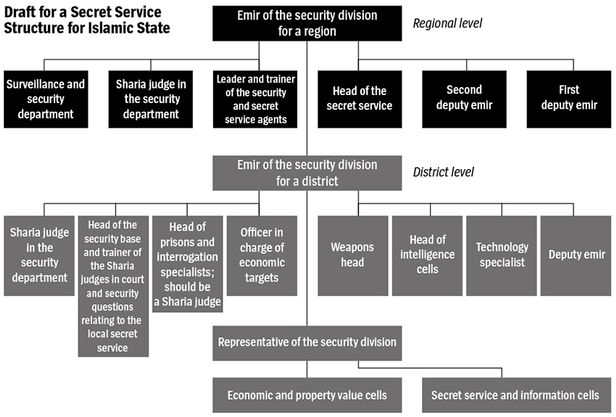

The highly-regarded German news magazine, Der Spiegel, provided the best, most authoritative account of ISIS. Entitled “Secret Files Reveal the Structure of Islamic State,” the report, based on captured documents, is a leak from German intelligence.

ISIS was established in Syria in 2012, a year after the civil war there began, as Der Spiegel explained. Samir Abd Muhammad al-Khilifawi, a “former colonel in the intelligence service of Saddam Hussein’s air defense forces,” was the brains behind it.

Known as “Hajji Bakr,” Khilifawi laid out a detailed plan for taking over swathes of Syria and Iraq by combining Saddam’s system of control through an intelligence state, with an appeal to religion.

“The nucleus of this godly state,” Der Spiegel wrote, “would be the demonic clockwork of a cell and commando structure designed to spread fear.”

Khilifawi and his closest colleagues, also former Iraqi intelligence officers, chose as “caliph,” an Iraqi, with a religious education: Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai, who used the alias, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

“They reasoned” that as “an educated cleric,” Samarrai “would give the group a religious face,” Der Spiegel said.

Samarrai was a figurehead. Like Mawla, who came from the Tal Afar area, Samarrai also came from northern Iraq: from Samarra, as his name suggests.

Both men were detained by US forces during the war in Iraq, formally known as Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and they were subsequently released.

Samarrai was captured in Feb. 2004, eleven months after OIF began. But US forces decided that he was not a significant figure and released him in late 2004.

Mawla was detained by US forces in Jan. 2008, following military operations in Mosul. CENTCOM described him as the deputy leader of Al Qaida in Iraq (AQI.) As long as US forces remained in Iraq, Mawla remained in detention. When they left in Dec. 2011, they turned Mawla over to the Baghdad government—which subsequently released him.

In 2013, Samarrai became the face of ISIS, as Der Spiegel explained. In 2019, he was killed in a US raid in Syria’s Idlib Province. Mawla replaced him and, similarly, died in a US raid in Idlib Province two weeks ago.

ISIS Predecessors

ISIS emerged out of AQI, as the State Department has explained. AQI was supposedly headed by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, a Jordanian, whose real name was Ahmad Fadil al-Nazal al-Khalayleh.

Some senior US officials recognized long ago that AQI was essentially the former Iraqi regime fighting to regain the status and power it lost with OIF. But their view never became the majority view.

“Almost no one says the real problem is that Saddam never surrendered. And even though he was captured, his people never surrendered,” Paul Wolfowitz, Deputy Secretary of Defense, told The Atlantic Monthly in Oct. 2004, part of a series of exchanges published in 2005, as “The Exit Interviews,” after Wolfowitz left the Pentagon to become head of the World Bank.

Saddam’s “organization is still operating as though they have a chance to win,” Wolfowitz continued, “and they’re allied with people who want to help them win—by which I mean the jihadis on the one side and the Syrian Baathists on the other.”

A few months later, in early 2005, a prominent Iraqi politician visited Washington. Speaking at a small dinner that included figures from the Pentagon and Vice-President’s office, as well as two major Washington think-tanks, the Iraqi made a similar point.

Neocons: Outsize, Outlandish Expectations about OIF

Virtually everyone at the dinner (although not this reporter) believed the US could transform the Middle East through democracy. Some 17 years later, that sounds ridiculous—and it was.

That view was based on a misreading of the collapse of the Soviet Union, and with it, the collapse of communism. The neocons saw it as an end to Russian authoritarianism, as well as the end of conflict between the two superpowers, as embodied in Frank Fukuyama’s book, “The End of History.”

Of course, as the Ukraine crisis shows, no such transformation occurred.

Read More: US warns of possible Russian attack on Ukraine next week, as European diplomacy proves fruitless

They followed that flawed assumption with a second flawed assumption: merely removing bad regimes would produce good ones.

No less a figure than US President George W. Bush was persuaded of this view, which was embodied in his Jan. 20, 2005, second inaugural address.

“It is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in the world,” Bush affirmed.

Peggy Noonan was a speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan, who did a lot to precipitate the collapse of the Soviet Union. Yet Noonan wrote a blistering commentary on Bush’s speech—which she called “mission inebriation.”

“Tyranny is a very bad thing and quite wicked, but one doesn’t expect we’re going to eradicate it any time soon,” she wrote. “This is not heaven, it’s earth.”

Indeed, one US official at the dinner would, two years later, tell this reporter, “I didn’t pay attention to what you said, because I thought we were going to do it all”—i.e., transform the Middle East through democracy.

The dinner’s host, a senior advisor to the Bush administration, would later complain to this reporter that his critics complained he had been frivolous about war. Unfortunately, they were right.

There are well-established principles about war-fighting—including “know the enemy.” But they were ignored while the counsel of sycophants was embraced.

More Accounts: Baathists behind “Islamic” Insurgency

At that dinner, the Iraqi politician complained the US had the relationship between terrorist states and terrorist groups “backwards.” Saddam’s regime was behind the insurgency, he said. Members of the deposed regime recognized that Iraqis had come to despise the Ba’ath party, so they adopted Islamic slogans and an Islamic appearance.

He was speaking about AQI, but a decade later, senior Kurdish officials described ISIS similarly.

The late Najmaldin Karim served as Governor of Kirkuk Province through most of the fight against ISIS. He spoke with Kurdistan 24 in late 2018 and was careful to limit his remarks to what he knew well: Kirkuk Province.

ISIS was “all local people,” Karim explained. “Peshmerga fought [ISIS] bravely, and hundreds of them were killed.”

“We have their pictures, their DNA,” he continued. “They’re all from the area.” They just grew beards, put on a dishdasha, and shouted Islamic slogans.

This reporter was earlier a cultural advisor to the US military in Afghanistan. In 2011, as I arrived, two men who had worked together over the previous year—a US Marine and British intelligence officer—briefed me, describing the enemy as “the losers in post 9/11 Afghanistan.”

That is very similar to Karim’s description of ISIS: the insurgent violence is driven by those who have lost power, status, and privilege.

In Afghanistan, I developed a good, working relationship with the officer who headed my unit. The army had difficulty understanding the population, and the contractors it employed were not much better.

Subsequently, this officer thought to establish a company to do that job, and I was to be his lead analyst. But a problem emerged: I said that ISIS was basically the former Iraqi regime with an Islamic cover. He strongly believed that was wrong.

So he arranged a meeting with the resident Middle East scholar at his base. The expert repeated the party line: ISIS was a religious movement, driven by an extremist ideology. But the expert’s knowledge was not greater than mine, and he was unconvincing.

In the end, this officer decided to re-enlist, rather than start a new business, and he deployed to Iraq to fight ISIS. When he returned, he said that I was right. He even suggested we write a book together.

A Better Way to Counter ISIS

One of the easiest ways to undermine and discredit ISIS is to describe it for what it is: a terrorist organization, established by the former Iraqi regime, which is using Islam to regain power—just as Der Spiegel explained.

In 2005, this reporter wrote a history of al-Qaida for the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment (ONA) and then briefed Pentagon officials, including the head of SOLIC (Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict.)

Afterward, he asked an unusual question: How much of the appeal of al-Qaida and similar organizations involves the frustrations of young men in traditional, conservative societies?

Subsequently, this reporter visited Iraq to work on another ONA project. Baghdad was dangerous, and I stayed in a compound, closed off to outsiders. We regularly took our meals in the house of a businessman living in the compound, a Sunni Arab from Anbar Province.

He had sent his 18-year old son to Egypt for safety, but the son was visiting his father over the summer. One day, only the son and I were present as lunch began, and he said something quite annoying.

He told me that although Osama bin Ladin and others like him did many bad things, they also did some good things—such as fight people like Saddam Hussein.

Why say something like that? He didn’t speak English, and I wondered if this was his first opportunity to cock a snook at a Western woman.

I replied that if it weren’t for the likes of Saddam Hussein, bin Ladin and those like him, couldn’t do what they did.

Shortly thereafter, his father appeared, and I recounted the conversation. He responded, “Oh, I quite agree with you.”

The father, of course, was concerned that his son would say anything positive, in any way, about the jihadis.

So I decided to see what the father’s response would be to the question from the head of SOLIC and asked what he thought about it.

“I quite agree,” the father responded. Then turning to his son, he said, “Wasn’t it a good idea, when I took you to see a prostitute, for your sixteenth birthday?”

The father certainly knew how to deal with his son.

The young man turned red as a beet, and we never again heard of the virtues of Osama bin Ladin et. al.