Reading ‘Iranian Love Stories’ as a New Wave of Young Women Fights Back in Iran

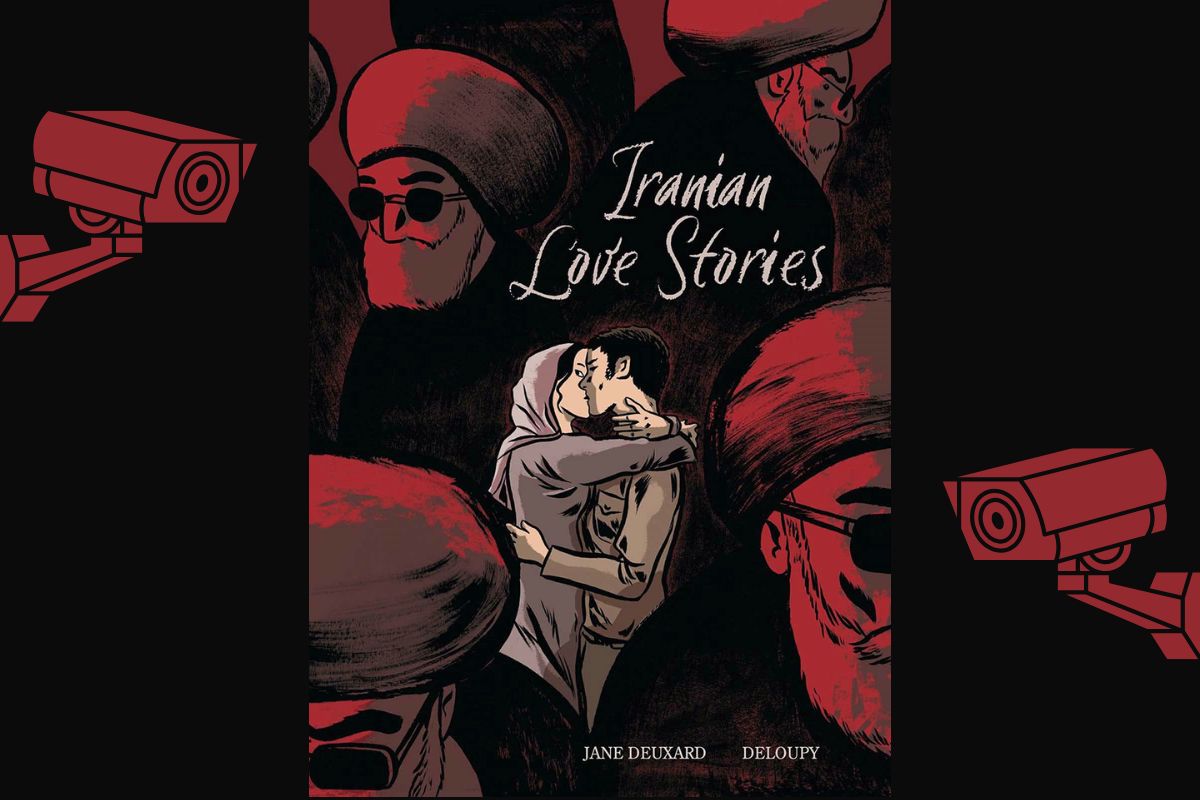

On the final The Mary Sue Book Club entry of 2021, I recommended a translated graphic novel by a French duo that goes by the pseudonyms Jane Deusart and the artist known professionally as Deloupy, entitled Iranian Love Stories. (The name “Jane Deusart” is a shared pseudonym between the two journalists and kept a secret to protect the people they spoke to.) This series of interviews in graphic novel form features vignettes of people aged 20 to 30 speaking on love, freedom, and politics (both intimately and more broadly) in Iran

Despite it appearing like this has nothing to do with the ongoing protest following the death of Mahsa Amini (22), there’s a lot in common, and this book lays the background as to why Gen Z is leading the current fight.)

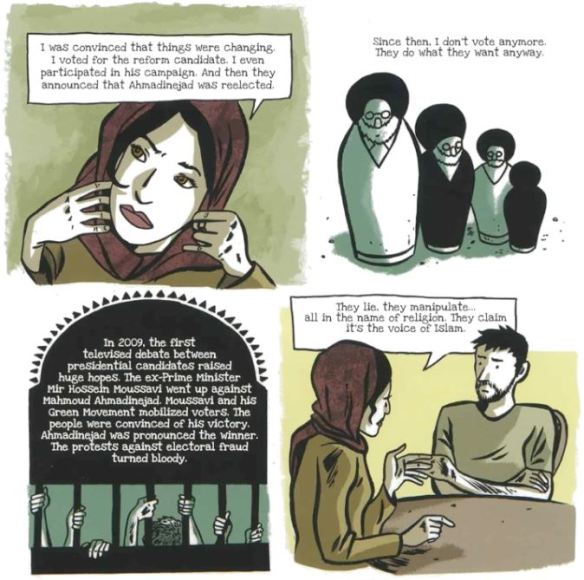

The journalists didn’t just speak to young people because they have less to lose and everything to gain from their stories being told. These Iranians speaking to the journalists (whose voices are mostly limited to a transition spread between chapters) were teenagers during the Green Movement in 2009. The crackdown and deaths color how they navigate contemporary Iran and their limited pushback against authority, even within their own family (who they put at risk by demonstrating in public or even interviewing for this book.)

More than about love

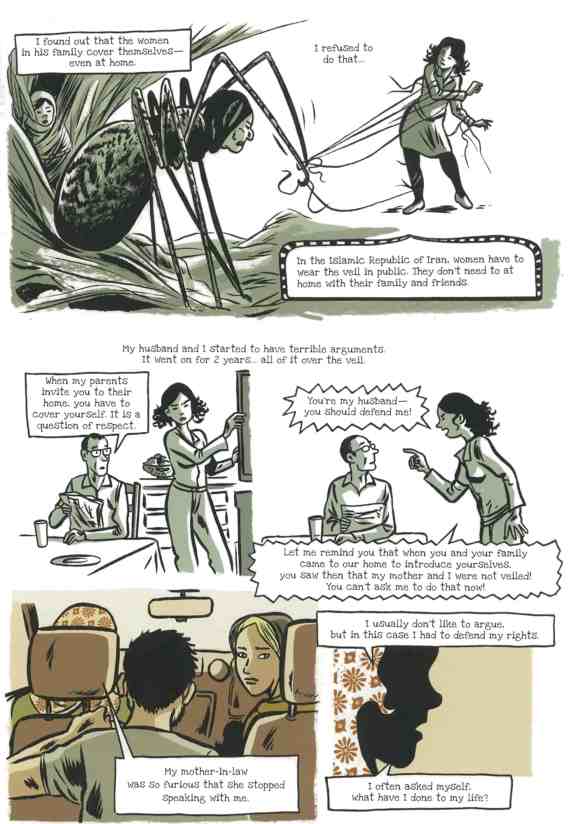

A significant portion of the book discusses actual love and relationships. Most of the romantic relationships (like the first section about Mila) involve secrecy, as getting found out before marriage can result in terrible consequences, especially for women. However, others include familial concerns. One man has dreamed of leaving and working abroad, but even if he could get out, he fears the state and morality police punishing his mother for his actions.

There’s also a story of a couple not quite being in sync because they didn’t get to know each other fully before moving in—thanks to strict laws in Iran. Even in their own homes, there is a division between politics and freedom.

Despite the title and focus of the novel, many of the Iranians interviewed don’t want love alone or, really, at all. They want choice, freedom, and hope. This is not dissimilar to the Green Movement or even the ongoing protest in Iran right now, in which the freedom for women to express themselves is the rallying cry, but is really the tipping point. Several of them, like 20-year-old Saviosh, have done everything “right” as far as going to college, etc., but cannot find work, and the U.S. sanctions at the time squeeze the economy.

Speaking of the economy, not everyone spoken to was wholly upset with the status quo. Because of extreme circumstances, one woman was allowed to leave the country regularly and made bank smuggling over goods. Another pair of women, Kimia and Zeinab, gawked at the idea of working and called American women’s wants misguided, as they felt a semblance of freedom in not wholly participating in public life. With all three of these women, despite general contentment, they did wish for more, but not enough to disrupt their chance of survival. Everyone finds small and large ways of rebelling.

The Green Movement

I’ve talked a lot about The Green Revolution without actually saying what it is. It began as a protest following the reelection of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. It’s widely considered the first social media resistance as it was largely organized online. The Arab Spring (proper) wouldn’t begin until 2011 or later, across the Arab region. Please note that most Iranians are Persian and speak Farsi (not Arabic), but are considered a part of the Arab or SWANA (South West Asia & North Africa) region.

Anyways, not to downplay the action in 2018, outside of the revolution that led Iran to become a semi-independent state, the most impactful protest in recent history is the Iranian Revolution (1979) and the Green Movement. Hundreds of people died in the 2009 protests, people disappeared, and cameras went up everywhere. In Iranian Love Stories, Vahid (26) meets the journalists at the largest cemetery in Iran and tells them, after the events of 2009 and the crackdowns after, he has nothing to lose.

As stated earlier, it’s not just love that guides these people or a single candidate running on reform that influences these young Iranians. They face jail time, public harassment, torture, and execution (regardless of age) for disobeying laws or being suspected of being under “Western” influence. The year before the election, 130 children were sentenced to death or were already awaiting execution. Iran’s government is set up as a theocratic democracy, so people can vote (including women), but a top religious leader can veto laws passed. Also, extremists have their own party in the Iranian government

Amplifying the voices of the current moment

Spurred by the death of Amini, this current moment is both very similar to The Green Movement and yet very different—even more so if justice is brought to the Iranians. Similarly, it is starting with a single grievance but is symbolic of larger issues. Also, like before, this is a protest growing through social media, especially TikTok, and the most vocal are teenagers and preteens.

However, unlike the initial spread mostly staying within Iran, these are spreading across the world. Anyone half paying attention is seeing the siege of college campuses by the morality police and the community gathering as women cut their hair and burn their compulsory hijabs. Also, still early into the protest, people are not demoralized and pessimistic about the idea of change like most of the people spoken to in the novel. Many current protesters and activists are asking for international attention.

Amini’s death so young and as a part of an ethnic minority group (her family is Kurdish) has created solidarity among them. This is under-discussed and reported on in the U.S. because of the way we tend to flatten people we deem so different from us, but this is still important.

Correction 10/24/2022: Initially, I wrote both Jane Deusart and Deloupy were pseudonyms. While Deusart is a secret name for the two journalists, Deloupy is the illustrator’s last name and the one he goes by professionally. This book featured two writers (journalists), and one artist.

(featured image: Graphic Mundi)