Jamaica and its people bear the scars of Europe’s royalty. Talk of ‘research’ into its atrocities is cheap

Carolyn Cooper

3 May 2023

People shopping at Coronation Market in downtown Kingston, Jamaica,

in 2019. The market is the oldest and largest in the Caribbean |

Bloomberg/Getty

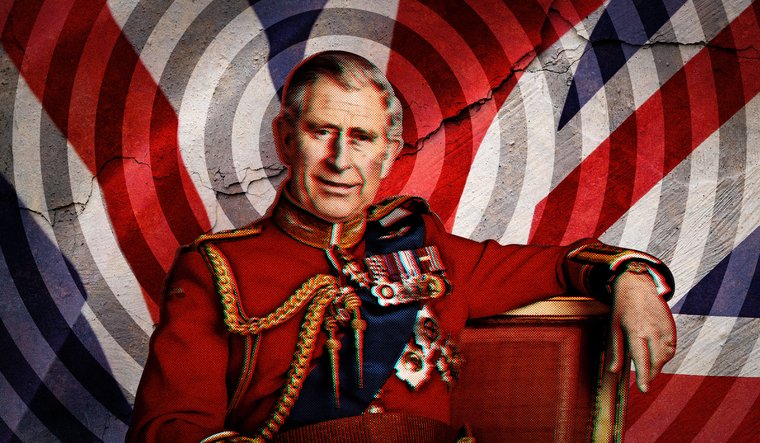

Hardcore royalists in Jamaica will be up by 1.30am on Saturday to watch live coverage of the prolonged build-up to the coronation of King Charles III.

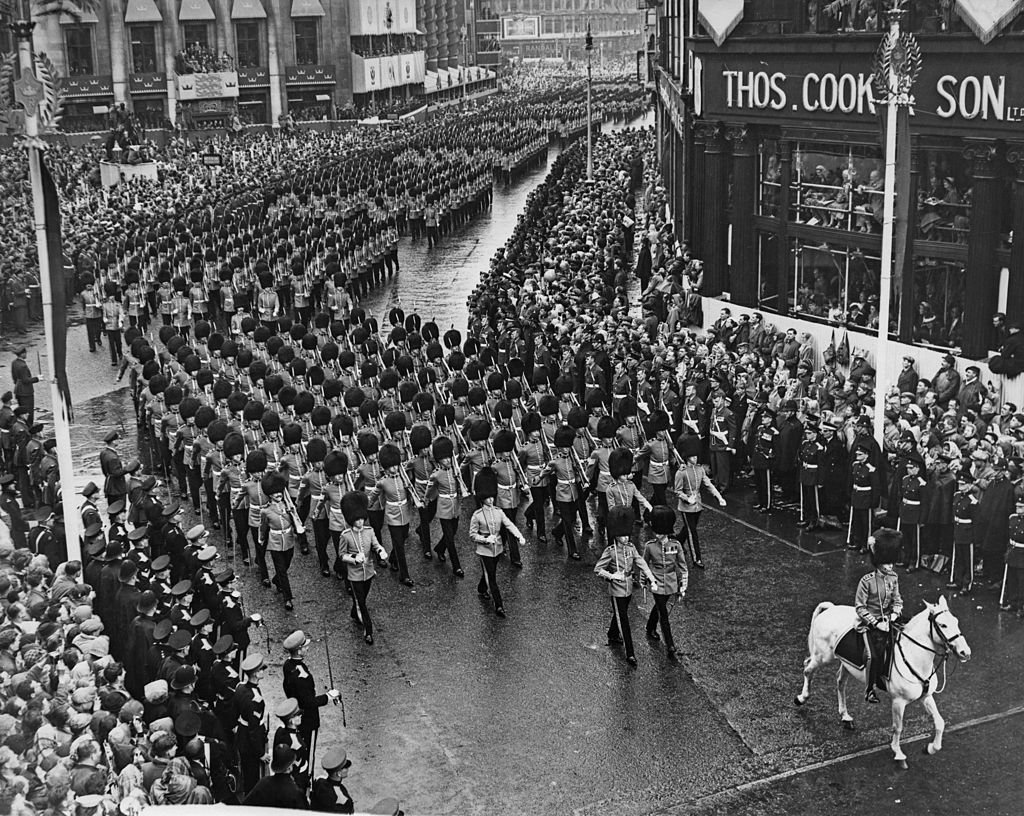

Two hours and 45 minutes later, it will be time for the main event. Royalists will revel in all of the pomp and ceremony. They will be dazzled by the regalia: the silver maces carried before the king; the Sword of State; the Sword of Temporal Justice; the Sword of Spiritual Justice; the Sword of Mercy; the Sovereign’s Ring made of a sapphire with a ruby cross set in diamonds; and the golden sceptres.

Most of all, the crowns! The St Edward’s, for the king, with its solid gold frame, decorated with rubies, amethysts, sapphires, garnet, topazes and tourmalines; and the resplendent Crown of Queen Mary, for the Queen Consort, blinging with the infamous Kohinoor diamond. Mined in India, the precious stone was presented to Queen Victoria in 1850 by the deputy chair of the East India Company. Blinkered royalists will not be at all troubled by unsettling questions about how the monarchy accumulated the gross wealth that will be so conspicuously displayed at the coronation.

For most Jamaicans, Saturday will be just another market day. In downtown Kingston, some shoppers will go to the Coronation Market, named in honour of Queen Victoria. The market is popularly known as ‘Curry’. This familiarising diminutive completely erases the monarchal origins of the name. Then there’s the Jubilee Market, again named for Queen Victoria. In addition, there are the sidewalk markets on East and West Queen Streets, Princess Street and King Street. The streets of the city of Kingston have been branded with the stigmata of royalty, just as the bodies of enslaved Africans were disfigured with the beastly stamp of ‘ownership’ administered by savage Europeans!

Centuries of atrocities

As Jamaica slowly engages in the process of becoming a republic, the British monarchy is being held to account for centuries of atrocities. The research has been done and the evidence is indisputable: successive kings and queens of England were engaged in the trafficking of enslaved Africans for 270 years.

In 2004, historian Nick Hazlewood’s eye-opening book ‘The Queen’s Slave Trader: John Hawkyns, Elizabeth I, and the Trafficking in Human Souls’ was published. Hazlewood painstakingly documented the role of the ‘Virgin Queen’ in the brutalisation of enslaved Africans. Elizabeth I entered into a heinous contract with the notorious pirate John Hawkins. She supplied a royal ship to transport human cargo in exchange for a share of the profit from the gruesome trade.

Almost two decades after Hazlewood’s book, Britain’s The Guardian newspaper published a report headlined ‘King Charles signals first explicit support for research into monarchy’s slavery ties’. According to a Buckingham Palace spokesperson quoted in the article: “Historic Royal Palaces is a partner in an independent research project, which began in October last year, that is exploring, among other issues, the links between the British monarchy and the transatlantic slave trade during the late 17th and 18th centuries.”

This “independent research project” comes rather late in the day. According to The Guardian, it is titled ‘Royal Enterprise: Reconsidering the Crown’s Engagement in Britain’s Emerging Empire, 1660-1775’ by Camilla De Koning, a PhD candidate at the University of Manchester. What is there to reconsider? The case is closed. One of the deadly enterprises in which the Crown was engaged was human trafficking. This ‘engagement’ cannot be reconceptualised in any other terms than as a classic manifestation of royal entitlement to brutality.

Bloomberg/Getty

Hardcore royalists in Jamaica will be up by 1.30am on Saturday to watch live coverage of the prolonged build-up to the coronation of King Charles III.

Two hours and 45 minutes later, it will be time for the main event. Royalists will revel in all of the pomp and ceremony. They will be dazzled by the regalia: the silver maces carried before the king; the Sword of State; the Sword of Temporal Justice; the Sword of Spiritual Justice; the Sword of Mercy; the Sovereign’s Ring made of a sapphire with a ruby cross set in diamonds; and the golden sceptres.

Most of all, the crowns! The St Edward’s, for the king, with its solid gold frame, decorated with rubies, amethysts, sapphires, garnet, topazes and tourmalines; and the resplendent Crown of Queen Mary, for the Queen Consort, blinging with the infamous Kohinoor diamond. Mined in India, the precious stone was presented to Queen Victoria in 1850 by the deputy chair of the East India Company. Blinkered royalists will not be at all troubled by unsettling questions about how the monarchy accumulated the gross wealth that will be so conspicuously displayed at the coronation.

For most Jamaicans, Saturday will be just another market day. In downtown Kingston, some shoppers will go to the Coronation Market, named in honour of Queen Victoria. The market is popularly known as ‘Curry’. This familiarising diminutive completely erases the monarchal origins of the name. Then there’s the Jubilee Market, again named for Queen Victoria. In addition, there are the sidewalk markets on East and West Queen Streets, Princess Street and King Street. The streets of the city of Kingston have been branded with the stigmata of royalty, just as the bodies of enslaved Africans were disfigured with the beastly stamp of ‘ownership’ administered by savage Europeans!

Centuries of atrocities

As Jamaica slowly engages in the process of becoming a republic, the British monarchy is being held to account for centuries of atrocities. The research has been done and the evidence is indisputable: successive kings and queens of England were engaged in the trafficking of enslaved Africans for 270 years.

In 2004, historian Nick Hazlewood’s eye-opening book ‘The Queen’s Slave Trader: John Hawkyns, Elizabeth I, and the Trafficking in Human Souls’ was published. Hazlewood painstakingly documented the role of the ‘Virgin Queen’ in the brutalisation of enslaved Africans. Elizabeth I entered into a heinous contract with the notorious pirate John Hawkins. She supplied a royal ship to transport human cargo in exchange for a share of the profit from the gruesome trade.

Almost two decades after Hazlewood’s book, Britain’s The Guardian newspaper published a report headlined ‘King Charles signals first explicit support for research into monarchy’s slavery ties’. According to a Buckingham Palace spokesperson quoted in the article: “Historic Royal Palaces is a partner in an independent research project, which began in October last year, that is exploring, among other issues, the links between the British monarchy and the transatlantic slave trade during the late 17th and 18th centuries.”

This “independent research project” comes rather late in the day. According to The Guardian, it is titled ‘Royal Enterprise: Reconsidering the Crown’s Engagement in Britain’s Emerging Empire, 1660-1775’ by Camilla De Koning, a PhD candidate at the University of Manchester. What is there to reconsider? The case is closed. One of the deadly enterprises in which the Crown was engaged was human trafficking. This ‘engagement’ cannot be reconceptualised in any other terms than as a classic manifestation of royal entitlement to brutality.

Rhetoric of sorrow

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) has outlined a ten-point plan for reparatory justice. First, there must be a full formal apology. Next, the right of descendants of enslaved Africans to be repatriated must be acknowledged and enabled through all legal and diplomatic channels. Repatriation has long been the cry of Rastafari in Jamaica and the diaspora. A development programme for indigenous Caribbean people must be implemented.

Cultural institutions must be established to educate Caribbean citizens about crimes against humanity. In addition, the public health crisis that has its roots in the poor diet of enslaved Africans must be addressed. Illiteracy must be eradicated and African knowledge systems – such as the Creole languages, like Jamaican, created by Africans in the diaspora – valorised. Rehabilitation for the psychological trauma inflicted upon African people and their descendents must be undertaken. Technology transfer, reversing some of Europe’s systematic exclusion of the Caribbean from global industrialisation, must be prioritised. Debt cancellation must be recognised as an essential element of reparatory justice.

King Charles’ “explicit support” for research on “the links between the British monarchy and the transatlantic slave trade” may prove to be just as flaccid as his repeated declaration of “profound sorrow” for the trafficking in Africans that was enabled by the monarchy. Talk is, indeed, very cheap. Further research is nothing but impotent deferral of vigorous action. King Charles must translate the rhetoric of sorrow into the truly meaningful language of immediate reparations.