Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

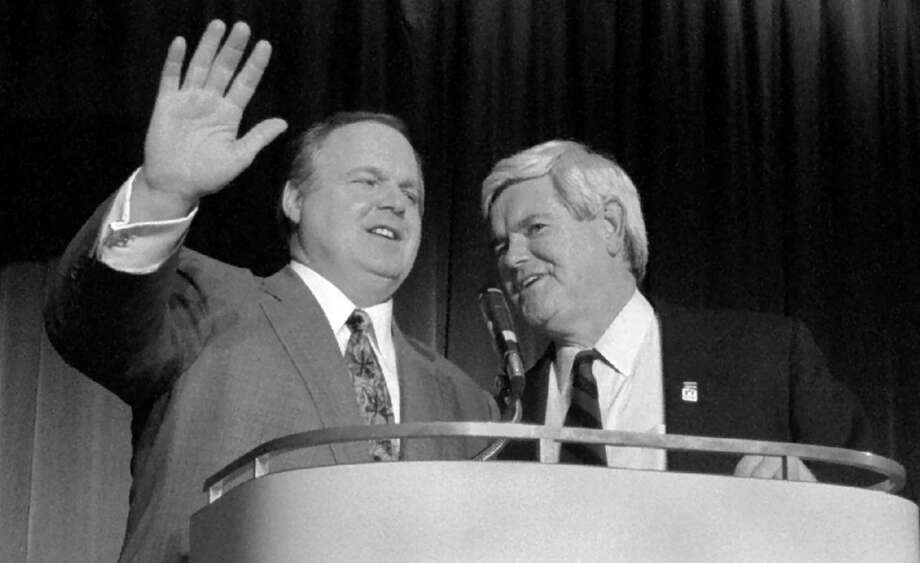

Rush Limbaugh’s death represents a moment for reflection on the state of American politics. Limbaugh amassed a fortune of more than $600 million over 32 years in the talk radio business, in the process building up more than 15 million regular listeners. It was no exaggeration when CNN referred to him as a “pioneer of AM talk-radio.” He made possible the rise of propagandistic partisan media, demonstrating that this format could be incredibly profitable for news channels looking for low-budget programming filled by pundits who tell audiences what they want to hear, while strengthening their prior beliefs and values.

Reflecting on Limbaugh’s legacy, The New York Times described the “rightwing” “megastar” by his “slashing, divisive style of mockery and grievance,” which “reshaped American conservatism.” CNN remembered him as a “conservative media icon who for decades used his perch as the king of talk-radio to shape the politics of both the Republican Party and nation.” MSNBC reported that Limbaugh was a “powerful and controversial voice in American politics” who was known for pushing a “conservative slant.”

One might have plausibly characterized Limbaugh as a conservative in the 1990s and 2000s, despite his conspiratorial paranoia against the Bill Clinton administration, and his long history of sexist and racist rants. But for those following his career over the last decade, it should be clear that Limbaugh had crossed over from conservative to neofascist in his politics. The racist and conspiratorial “birther” nonsense Limbaugh trafficked in during the late 2000s and early 2010s, his reference to liberal activist Sandra Fluke as a “slut” and a “prostitute,” his labeling of feminists as “Feminazis,” and his incessant race-baiting by trafficking in anti-black stereotypes and rhetoric, all reinforced his profile as a rightwing ideologue who had long straddled the line between conservative and far-right reactionary. But during the Trump years and in the run-up to them, Limbaugh’s politics became noticeably more extreme, as the Republican Party itself moved further and further toward embracing neofascistic politics.

This piece is not devoted to the “greatest hits” of Rush Limbaugh cliches that have gotten so much attention among critics. Rather, I review the most extreme of Limbaugh’s comments in recent years that have consistently been swept under the rug in mainstream academic, journalistic, and Democratic discourse. The simple reason for why you probably haven’t heard most of these statements is because they reveal Limbaugh’s politics to be neofascistic, and referring to a powerful pundit like Limbaugh in those terms simply will not do in polite society. In a country that has long convinced itself, in Sinclair Lewis’s famous words, that “It Can’t Happen Here,” American political culture simply won’t allow for the possibility that the U.S. has become neofascistic in its politics.

To be clear, when I talk about “neofascism,” I’m referring to a school of thought established by social scientists and journalists recognizing that, while the exact features of classical Italian and German fascism are not going to repeat themselves in future settings, we may observe enough of an overlap between the features of classical fascist regimes and current political contexts to speak of an updated, contemporary version of (neo)fascistic politics. More specifically, I am referring to a constellation of traits that relate to neofascistic politics, including the embrace of white supremacy, the rampant trafficking in conspiratorialism fueled by the cult of personality of a demagogic leader, support for paramilitarism and the romanticization of eliminationist rhetoric and violence against alleged enemies of The Leader, efforts to idealize and impose one-party rule, and Orwellian efforts to gaslight political critics by inverting reality and trafficking in blatant propaganda. I explore each of these traits, related to Limbaugh, below.

White Supremacy

Limbaugh’s bigotry never fit the conventional mold of white supremacists donning Klan robes or goosestepping Nazis shouting “Sieg Heil” to The Fuhrer. Modern white supremacy is much more subtle than that; its advocates have spent years – decades really – mainstreaming their hate rhetoric to a popular audience, while denying that they are trafficking in neofascistic themes. Limbaugh pioneered this form of white supremacist hate, although the primary target wasn’t black Americans, but Muslims and undocumented immigrants.

Limbaugh’s Islamophobia was unrelenting. He referred to Muslims in blanket negative terms, including:

1) The position that Muslims are unintelligent and incapable of serious intellectual accomplishments, reflected in Limbaugh’s comparison between “the number of Muslims who have been Nobel prize winners to the number of Jews who have been Nobel prize winners,” which he declared no “contest.” Limbaugh was clear that he believed “Muslim contributions to science and math are myths.”

2) The belief that Muslims are contemptuous of democracy, via Limbaugh’s claim that “there is not a Muslim nation democratic in the way we are anywhere in the world,” and by his dismissal of the 2011 democratic Egyptian uprising as a phony revolution pursued under the “guise” of democracy.

3) The contention that Muslims represent a fifth column in their alleged efforts to take over American politics, evidenced by his wild conspiratorial fearmongering – which was rejected as “dangerous” by Congressional Republican leadership – about the Muslim Brotherhood taking over the State Department through the “presence of Huma Abedin,” one of “Hillary Clinton’s top-level aides,” who Limbaugh described as “so close to the powers that be.” Abedin’s position concerned Limbaugh because, as he explained, “Human’s mother is best friends with the wife of the new Muslim Brotherhood President of Egypt.”

4) The myth that the public was in “panic” that “Obama is a Muslim,” with Limbaugh’s Islamophobia buttressed by references to the President as “Imam Hussein Obama,” and his claim that the President was a “defender of Islam,” and dead-set on “constantly denigrating Christians.” Limbaugh characterized Muslims as a foreign, exotic other, via his denigration of Obama for claiming Muslims are “a part of the fabric of America,” to which Limbaugh responded that he “didn’t know that.”

5) The position that Muslims represent a terrorist threat to the nation, via Limbaugh’s objection to distinguishing between “Islamic extremism” and “all of Muslims,” and his contention that “in a more sensible time,” “we did not say ‘German Nazis’ – we said ‘Germans’ or ‘Nazis’ and put the burden on non-Nazi Germans, rather than on ourselves, to separate themselves from the aggressors.”

Limbaugh’s white supremacy extended to his attacks on undocumented immigrants. Drawing on classic fascist themes out of Hitler’s Third Reich, Limbaugh referred to Latin American immigrants as an “invasive species,” comparing them to “mollusks,” while depicting them as an “invasion force” that “contributes to the overall deterioration of the culture of this society.” Limbaugh lamented that “we have now imported the third world,” and “they have not assimilated.” He warned that, due to undocumented immigrants, “we are at the forefront of a dissolution of a nation” – facing the “breakdown of organized society.” Perhaps not-so-subtly drawing parallels to Nazi-era propaganda and the purity of the nation and its racial and ethnic identity, Limbaugh warned about unauthorized immigration that “the objective is to dilute and eventually eliminate or erase what is known as the distinct or unique American culture…this is why people call this an invasion.” And Limbaugh recycled Nazi propaganda depicting Jews as an infection when he wonderedaloud about the “dangers of catching diseases when you sleep with illegal aliens.” When taken together, these comments reveal that Limbaugh was a shrewd operator. He was a bigot, consistently smuggling white supremacist themes into his programs, while being careful to avoid recognizing what he was doing, and counting on his listeners’ ignorance to obscure his recycling of Nazi-style white supremacist propaganda.

Conspiracy Theories and the Cult of Personality

Limbaugh made sure his political fortunes were inseparably linked to Donald Trump’s. This was abundantly clear in his conspiratorial rhetoric. He took as articles of faith the former President’s baseless “election fraud” propaganda, coupled with other wild conjecture about Democratic plots to take down Trump. Limbaugh speculated that the Democratic Party was attempting to infect Trump with Covid-19, that “radical leftists” and “the Democratic Party” had engaged in a “fraud” to “beat Trump” via “ballot harvesting” and other election scams in battleground states; that the Covid-19 lockdown represented an effort “to take down the U.S. economy” by imposing “globalism and world government”; that the official Covid-19 death counts were inflated due to “fake causes” listed “on death certificates” and the “staged overrunning of hospitals”; and that newly reported Covid-19 cases were “being reported in states that Trump needs to win,” implying that these cases were part of a coordinated Democratic effort to undermine the former President’s candidacy. None of these assertions were accurate. But fascists aren’t exactly known for embracing leaders who rationally engage in empirical evidence.

Conspiratorial Eliminationism

Closely overlapping with Limbaugh’s white supremacy was his conspiratorial eliminationism, which focused on black Americans and the Democratic Party. During the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Limbaugh demonized people of color, stoking fear via his talk about “saving America from a race war that the Democrats are out there actively trying to promote…they want chaos, they want this constant us-versus-them aspect of daily life.” In contrast, Limbaugh claimed, Trump was “making it clear that he’s interested in people who are constructive, productive, generally happy. He’s not interested in parasites, the generally miserable.” The “parasites” reference was another example of Trump’s eliminationist rhetoric, echoing Nazi propaganda, but directed against the Republican Party’s political enemies. Limbaugh was equally vicious in his targeting of Black Lives Matter, which he classified as “Marxist” and a “full-fledged anti-American organization.” Limbaugh’s eliminationism also extended to LGBTQ activists, which he condemned for working with the “deep state” to impose a “30 years” long “cultural rot” in America. “What a cesspool the Democrat Party has turned the country into, what a cesspool American morality has become, what a cesspool the American left is turning our culture into,” Limbaugh lamented, as the country “descend[s]” into “a filthy gutter” politics dominated by “transgenders” and “gay people” fighting for, and winning equal rights. Such incendiary rhetoric was clearly intended to reinforce the belief in listeners’ minds that the U.S. was divided between two peoples – the hard working and the virtuous on the one hand, and the morally depraved and the rotten on the other. This language mirrored Nazi propaganda, which pitted notions of an impure minority against the lost purity and greatness of the nation’s past.

Eliminationism and Paramilitarism in Pursuit of One-Party Rule

Limbaugh was pining for civil war well before the events of January 6th at the U.S. Capitol building. He spoke romantically about rightwing paramilitary-style activists, referencing Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter by name in mid-2020, wondering: “Well, where are all the people with guns to ‘push back’ against the left? They’re [the left] threatening to beat you upside the head and do whatever other kind of physical damage to you they can.” Limbaugh called on “armed right-wingers” to “push back against the Democrats, against the left, against the media…who’s got all the guns in this country? We’ve got all the guns,” but the right was “not pushing back. If there’s no pushback and if the pushback isn’t seen, then people are going to get dispirited and think nobody cares about this assault on the country.”

Limbaugh eventually got what he wanted, as neofascist Trump supporters stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6thseeking to overturn certification of Democratic President-elect Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 election. At the time, Limbaugh announced that “I actually think that we’re trending toward secession…there cannot be a peaceful coexistence” with “two completely different theories of life, theories of government” which he claimed divided American politics between left and right, and between Democrats and Republicans. Reinforcing this position, Limbaugh romanticized the Capitol insurrectionists, which he likened to Revolutionary War era rebels and patriots: “We’re supposed to be horrified by the protesters…There’s a lot of people out there calling for the end of violence…lot of conservatives, social media, who say that any violence or aggression at all is unacceptable regardless of the circumstances. I am glad Sam Adams, Thomas Paine, the actual tea party guys, the men at Lexington and Concord, didn’t feel that way.” Such statements made clear Limbaugh’s support for paramilitary efforts to impose one-party rule by overturning the 2020 election.

Gaslighting the Public on Neofascism

With such an egregious record of trafficking in, and embracing neofascistic political rhetoric, the rational observer should be asking a simple question: how did Limbaugh get away with it without being run out of the “conservative” media? One answer is that rightwing pundits have become expert gas lighters, smuggling in white supremacist and neofascistic rhetoric into their programs, while consistently stopping short of admitting this is what they’re doing. They rely on the staggering historical ignorance of their audiences, whom they correctly believe know little about classical fascism, and will not notice that they’re smuggling into programs extremist discourse, even as their followers come to embrace neofascistic political ideology.

A second way they get away with it is because the right projects their own neofascistic politics onto critics in Orwellian ways that seek to erase or invert reality. Limbaugh was only one of many pundits, including Mark Levin, Glenn Greenwald, and Tucker Carlson, who claim that white supremacy and paramilitarism on the right do not exist, or that they are being promoted instead by the Democrats and their supporters. Limbaugh echoed this position, maintainingthat “white supremacy or white privilege is a construct of today’s Democratic Party,” and that they “are such a small number – you could put them in a phone booth.” Such a position, of course, is absurd considering that the former President and rightwing media spent years normalizing white supremacist and neofascistic political ideology, to the point where one in ten Americans and a third of Republicans say it is acceptable to hold neo-Nazi views, a third of the country engages in some form of Holocaust-denial, and a third agree that the U.S. should “protect and preserve its White European heritage.”

The United States has entered a crisis moment, fueled by the ascendance of rightwing extremism. The realities of neofascistic politics are being swept under the rug because it simply “won’t do” to admit that large numbers of Americans have embraced the ideology of hate. There is little hope of moving forward and beating back this extremism until Americans are honest about how pervasive the problem has become. “Conservative” media venues have been empowering and enriching the merchants of hate for years. We should remember this toxic history when we reflect on the legacy of Rush Limbaugh and his impact on American values and discourse.