Arms Makers Target Kids to Boost Sales

Originally published by Truthout.

In August, authorities in Hondo, Texas, revoked a permit for an NRA-affiliated group to hold its fundraiser on city property. The event featured a raffle for an AR-15, the same assault rifle that slaughtered 21 people in nearby Uvalde last May. At a city council meeting, families of the victims read the names of the slain, cradled their portraits, and denounced the arms lobby’s audacity. “It is a slap in the face to all of Uvalde,” explained Jazmin Cazares, who lost a sister in the massacre.

As gun ownership in the U.S. declines, arms makers have embraced the youth market to avoid industry contraction. Trade magazines such as Junior Shooters openly market rifles to children. And a recent lawsuit revealed that Remington sales tactics target minors.

The confrontation between Uvalde families and the NRA highlights the polarizing strategy and political heft of arms makers. Yet it also reveals their irreducibly economic interests. Although the industry claims to defend the Constitution and individual liberty, it has spawned a gun violence epidemic by liberalizing markets and aggressively pursuing profits.

The Political Turn

For half a century, arms makers have mobilized to destroy barriers to the industry’s growth and profits. Indeed, the modern gun lobby coalesced in response to mounting pressure for gun control.

In 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated President John F. Kennedy with a Mannlicher-Carcano, a surplus rifle that he purchased through the NRA’s American Rifleman magazine. Three years later, a sniper at the University of Texas at Austin killed 14 people, further fueling calls for reform and inspiring Peter Bogdanovich to film his classic thriller, Targets.

After shooters felled Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Gun Control Act (1968), imposing regulations on mail order purchases and prohibiting those with felony convictions, drug users and people with intellectual disabilities from buying arms.

Its passage triggered fierce industry resistance. In reaction, arms makers converted their economic clout into political power by wading into the nascent culture wars. They turned guns into potent symbols of American masculinity, grassroots democracy and rugged individualism by evoking the mythos of the frontier and feeding nostalgia for an imagined past of consensus, tradition and harmony.

By the late 1970s Harlon Carter led the NRA, while pioneering the brand of reactionary populism that Donald Trump later adopted. In particular, he employed the coded rhetoric of “law and order” to talk about race and promote arms sales in the same breath. Before joining border patrol, Carter murdered a Latino boy in Texas, brutally enforcing the color line.

Under his leadership, the industry propounded an “individual rights” interpretation of the Second Amendment, claiming that the Constitution enshrined the right of all citizens to own guns—a novel argument that held little water in legal circles.

Populist Gunslingers

In 1980, the NRA entered the electoral fray by endorsing Ronald Reagan for president. The decision had layers of symbolism; Reagan was a former actor who previously starred in the very Westerns that gave American gun culture much of its ideological content and allure.

Over the next two decades, the NRA became the vanguard of the New Right, as conservatives waged cultural warfare, mobilizing voters over topics such as gun control, abortion and gay marriage. To maintain popular militancy, the lobby fostered a sense of permanent crisis. NRA ads were shrill, featuring headlines like “How Much Tape Is Too Much When He Threatens to Kill You?”

Privately, officials bragged that they “pour gasoline on the fire.”

But their words have sown firestorms. In the spring of 1995, Vice President Wayne LaPierre claimed that “jack-booted Government thugs” are poised to “take away our constitutional rights, break in our doors, seize our guns, destroy our property and even injure and kill us.” Shortly afterward, the veteran NRA member Timothy McVeigh bombed a federal building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. McVeigh believed the government conspired to confiscate his guns.

The NRA navigated the fallout by naming Charlton Heston president. Under Heston, membership soared to 4 million, and the organization helped elect George W. Bush in 2000 by a razor-thin margin. The election instilled fear of the NRA among Democrats, who remained silent on gun control for the next decade.

Best known for starring in The Ten Commandments, Heston perfectly fused religious zeal with nationalist conviction. To the NRA faithful, he was an American Moses. He represented the endangered America that heartland conservatives saw in themselves; the leader guiding the remnant of the nation that remaine —like ancient Israel—exiles in their own country, while clinging to the Second Amendment as sacred scripture.

Indeed, Heston depicted gun owners as a threatened minority. “I remember when European Jews feared to admit their faith. The Nazis forced them to wear yellow stars as identity badges. So,” Heston asked, “what color star will they pin on gun owners’ chests?”

Industry Capture

Under his leadership, the lobby launched a legislative offensive. In 2003, the NRA guided passage of the Tiahrt Amendment, which inhibits the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives from publicly identifying crime weapons and sharing evidence with law enforcement. The next year, corporate pressure blocked renewal of the assault rifle ban. Then in 2005, the industry rammed the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA) through Congress, shielding companies from lawsuits when crimes involve their guns.

Ultimately, the industry’s biggest victory occurred in 2008, when the Supreme Court accepted its ample reading of the Second Amendment in D.C. v. Heller. Its fingerprints were all over the ruling. The case’s mastermind, Robert Levy, was a fellow at the Cato Institute, a conservative think tank co-founded by Charles Koch of the Koch brothers. And only months before the ruling, Charles Koch hosted Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas at his personal retreat.

Arms makers had already embedded Scalia in their camp. In 2007, the World Forum on the Future of Sport Shooting Activities (WFSA), an international offshoot of the NRA, awarded him its “Sport Shooting Ambassador Award” — turning him into an honorary lobbyist. His majority opinion in Heller heavily cited scholarship that the NRA funded.

Meanwhile, the industry invested in lobbying. Between 2005 and April 2011, “corporate partners” contributed between $14.7 and $38.9 million to the NRA. While publicly denying the nonprofit received industry funds, LaPierre informed executives that it was “geared toward your company’s corporate interests.” Beretta, Glock, Ruger, and other firms generously contributed to its coffers. CEO James Debney of Smith & Wesson explained that the NRA is “our voice.”

Targeting Children

Yet gradually, a trail of mass shootings shifted public opinion and drained the industry’s legitimacy. In 2012, the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting in Newtown Connecticut became one of the deadliest in U.S. history, while gripping the community with muted symbolism: The sleepy town was the headquarters of the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF)—the official industry lobby. A future NRA director, Joshua Powell, recalls preparing for combat. As “the bodies… were still bleeding,” Powell admits, he and his colleagues “quickly moved into fighting mode…. The adrenaline and seductive intensity of the fight was palpable. It was all I could focus on.”

Powell describes the immediate and growling response of Ackerman-McQueen, the NRA’s publicity firm: “We’re not giving a fucking inch.” Under its guidance, Vice President LaPierre assured the country, “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

Yet the massacre was a turning point, galvanizing a movement for gun control, fracturing faith in the industry line, and driving a wedge between cautious Democrats and the NRA. By then, the effects of gun violence were graphically clear. Between Columbine in 1999 and 2021, over 240,000 students were on campuses during shootings. In the 2017-2018 school year alone, at least 4.1 million children—and possibly up to 10 percent of the country’s student body—participated in lockdowns. Across the nation, kids scribbled out wills and texted loved ones goodbye.

Incredibly, Thompson/Center Arms had previously debuted a tiny gun for six-year-olds.

To temper public anger after Sandy Hook, the NRA promoted its Eddie Eagle program, which teaches children proper gun etiquette. The American Academy of Pediatrics concluded that it was ineffectual. Still, the NRA hired education specialist Lisa Monroe of Oklahoma University to revamp it in 2015. She only learned afterward that the industry proposed it as an alternative to child access laws. “If they had,” Monroe stressed, “I wouldn’t have anything to do with it.”

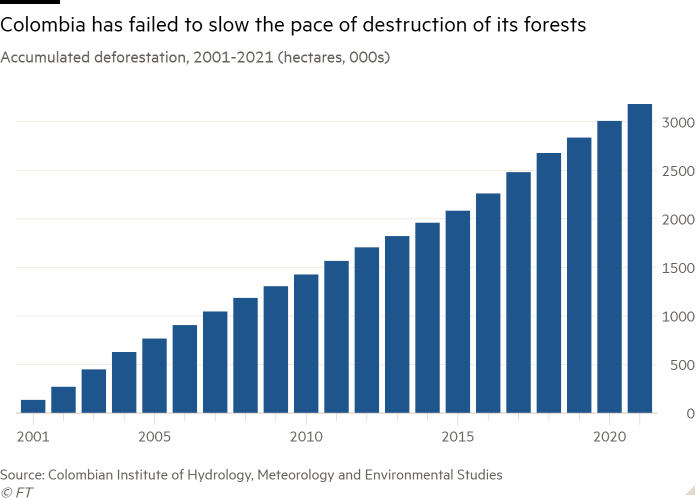

Founder Shannon Watts of Moms Demand Action asserts that Eddie Eagle is “a propaganda tool, similar to Joe Camel in marketing cigarettes to kids.” Her critique is painfully plausible. In recent decades, gun ownership has fallen drastically in the United States. While claiming to promote child safety, companies aggressively market to young customers, in order to ensure the social reproduction of the industry and its political base.

“What market isn’t tied to juniors?” Junior Shooters stressed the year of Sandy Hook. The NSSF and NRA sponsor the magazine, which targets children and features advertisements for assault rifles. One sponsor, Bushmaster Firearms, produced the AR-15 that tore apart Newtown; the title of one article was “Why I Love Bushmaster AR-15s… You Should, Too.”

Incredibly, Thompson/Center Arms had previously debuted a tiny gun for six-year-olds. Marlin appealed to children with a real-life “Marlin Man” (again the Joe Camel comparison beckons), while introducing a new rifle line. “These rifles are not just sized for kids,” the company boasted, “they’re completely designed for kids.”

Leading firms, such as Smith & Wesson and Beretta even offer “youth model” assault rifles, favoring plastic components that minimize recoil and flashy colors that attract children. And while making customers, they spread gun culture. Advertising imbues the weapons with emotional heft, fostering the fanatical attachment and easy access to arms that shooters from Columbine to Newtown have made notorious.

Simply put, children with assault rifles are not an anomaly. Rather, they embody two main industry trends. For decades, firms have both expanded and militarized the civilian market. In a country already saturated with guns, companies boost lethality to artificially stoke demand and attract new customers—including children. Firms rely on their orders to achieve economies of scale for military-grade weapons. And perversely, they sell arms to law enforcement to enhance their appeal in the larger and more profitable civilian market.

Globalizing the Second Amendment

Most media coverage focuses on domestic shootings, but the gun violence epidemic bleeds across borders. Beyond children, the industry vigorously pursues foreign clients. Under Secretary of State John Bolton and NRA officials led the U.S. delegation to the UN talks that culminated in the Arms Trade Treaty (2013), opposing any attempt to restrict arms flows. Later, Bolton himself became an NRA director and oversaw an export boom as national security advisor.

Industry officials even pursued the Russian market. In 2015, the NRA funded a trip to Russia for its directors, who illegally exploited it to pursue business deals and meet officials on the U.S. Treasury’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list.

Future NRA president Peter Brownell emphasized that he came seeking “an import or export opportunity.” Russian liaisons assured him that the trip “would DEFINITELY be profitable.” Afterward, a congressional investigation concluded that Russia manipulated the NRA to penetrate conservative circles and conduct espionage.

Yet the industry’s shadow hangs heaviest south of the border. Approximately 70 percent of gun crimes in Mexico involve U.S. arms, which flow in an iron torrent over the Rio Grande. Even European firms like Glock and Beretta exploit U.S. law to circumvent export controls in their own countries and inundate the region with bullets. When the U.S. assault weapons ban elapsed in 2004, homicide rates in Mexico skyrocketed. That year, only one-fourth of homicides involved a gun; by 2019, the figure was 72 percent.

As cartels and authorities pursued a relentless arms race, Mexico’s homicide rate topped 164,000 people in seven years. In 2014, U.S. guns notoriously facilitated the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa, who were about to commemorate the Tlatelolco Massacre—another atrocity involving U.S. arms.

Still, the industry blocked reform. The NRA announced a “battle” to guarantee legislators “do not use Mexico as an excuse to sacrifice our Second Amendment rights.” That fight is ongoing. Last year, Mexico sued 11 arms firms in federal court in Boston, claiming they knowingly fuel the violence.

In sum, the industry has fostered violence in the Americas, where six countries alone accounted for over half the globe’s gun-related deaths in 2018. Yet while dismantling barriers to accumulation, the NRA’s conservative base constructs border walls for the very refugees fleeing the bloodshed.

Value in Motion

In 2018, a teenager at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida followed a worn-out script, slaughtering 17 people with an AR-15. But common sense had evolved, and the country was in a boiling mood. The next month, students in 90 percent of voting districts protested arms violence. Gun control activists outspent the industry for the first time that year in elections.

By then, the organization was in shambles, facing bankruptcy, sex scandals and corruption charges. Powell admits that the “waste and dysfunction” was “staggering.” Despite the organization’s nonprofit status, directors practiced nepotism, siphoned funds and funneled contracts to friends. A former senior IRS official called its case “extraordinary”—“one of the broadest arrays of likely transgressions that I’ve ever seen.”

The disgraceful saga reached its climax on January 6, 2021, as protesters converged on the Capitol to contest the presidential election and reinstall Donald Trump, who received massive industry donations. Days before, LaPierre warned about “armed government agents storming your house,” while exhorting conservatives to “STOP GUN CONFISCATION.” In response, gun rights activists invaded the Capitol, including Richard Barnett, who seized House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office, and William Calhoun, who declared he would sling “enough hot lead” to stack bodies “like cordwood.”

Since then, the January 6 coup and an interminable string of mass shootings has electrified demands for reform. This summer, President Joe Biden signed a bill that bolsters background checks, mental health care and school security. And a judge ruled that a lawsuit against the NRA for violations of its nonprofit status can continue.

Yet the industry’s political base remains powerful, and the race for accumulation persists. For if the subtext of gun rights includes white nationalism and virulent anti-statism, it also includes profit. From the industry’s standpoint, shattering bullets are simply value in motion. In many ways, this history is a withering commentary on the corrosive power of capitalism; the mirror of a society where child sacrifice is tribute to the Second Amendment, and the Second Amendment protects corporate profit. As the U.S. further polarizes, the gun debate illuminates dividing lines with fire and lead.

The author would like to thank Sarah Priscilla Lee of the Learning Sciences Program at Northwestern University for reviewing this article.

Copyright, Truthout.org