War Cuts the Heart Out of Humankind

Photo by mohammed al bardawil

In the apartment of my friends in Baghdad (Iraq), they tell me about how each of them had been impacted by the ugliness of the 2003 U.S.-imposed illegal war on their country. Yusuf and Anisa are both members of the Federation of Journalists of Iraq and both have experience as “stringers” for Western media companies that came to Baghdad amid the war. When I first went to their apartment for dinner in the well-positioned Waziriyah neighborhood, I was struck by the fact that Anisa—whom I had known as a secular person—wore a veil on her face. “I wear this scarf,” Anisa said to me later in the evening, “to hide the scar on my jaw and neck, the scar made by a bullet wound from a U.S. soldier who panicked after an IED [improvised explosive device] went off beside his patrol.”

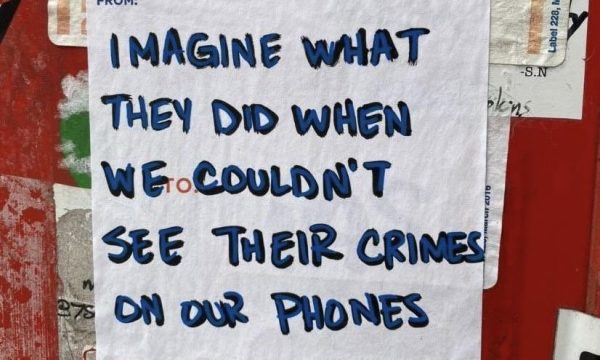

Earlier in the day, Yusuf had taken me around New Baghdad City, where in 2007 an Apache helicopter had killed almost twenty civilians and injured two children. Among the dead were two journalists who worked for Reuters, Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen. “This is where they were killed,” Yusuf tells me as he points to the square. “And this is where Saleh [Matasher Tomal] parked his minivan to rescue Saeed, who had not yet died. And this is where the Apache shot at the minivan, grievously injuring Saleh’s children, Sajad and Duah.” I was interested in this place because the entire incident was captured on film by the U.S. military and released by Wikileaks as “Collateral Murder.” Julian Assange is in prison largely because he led the team that released this video (he has now received the right to challenge in a UK court his extradition to the United States). The video presented direct evidence of a horrific war crime.

“No one in our neighborhood has been untouched by the violence. We are a society that has been traumatized,” Anisa said to me in the evening. “Take my neighbor for instance. She lost her mother in a bombing and her husband is blind because of another bombing.” The stories fill my notebook. They are endless. Every society that has experienced the kind of warfare faced by the Iraqis, and now by the Palestinians, is deeply scarred. It is hard to recover from such violence.

My Poisoned Land

I am walking near the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Vietnam. My friends who are showing me the area point to the fields that surround it and say that this land has been so poisoned by the United States dropping Agent Orange that they do not think food can be produced here for generations. The U.S. dropped at least 74 million liters of chemicals, mostly Agent Orange, on Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, with the focus for many years being this supply line that ran from the north to the south. The spray of these chemicals struck the bodies of at least five million Vietnamese and mutilated the land.

A Vietnamese journalist Trân Tô Nga published Ma terre empoisonnée (My poisoned land) in 2016 as a way to call attention to the atrocity that has continued to impact Vietnam over four decades after the U.S. lost the war. In her book, Trân Tô Nga describes how as a journalist in 1966 she was sprayed by a U.S. Air Force Fairchild C-123 with a strange chemical. She wiped it off and went ahead through the jungle, inhaling the poisons dropped from the sky. When her daughter was born two years later, she died in infancy from the impact of Agent Orange on Trân Tô Nga. “The people from that village over there,” my guides tell me, naming the village, “birth children with severe defects generation after generation.”

Gaza

These memories come back in the context of Gaza. The focus is often on the dead and of the destruction of the landscape. But there are other enduring parts of modern warfare that are hard to calculate. There is the immense sound of war, the noise of bombardment and of cries, the noises that go deep into the consciousness of young children and mark them for their entire lives. There are children in Gaza, for example, who were born in 2006 and are now eighteen, who have seen wars at their birth in 2006, then in 2008-09, 2012, 2014, 2021, and now, 2023-24. The gaps between these major bombardments have been punctuated by smaller bombardments, as noisy and as deadly.

Then there is the dust. Modern construction uses a range of toxic materials. Indeed, in 1982, the World Health Organization recognized a phenomenon called “sick building syndrome,” which is when a person falls ill due to the toxic material used to construct modern buildings. Imagine that a 2,000-pound MK84 bomb lands on a building and imagine the toxic dust that flies about and lingers both in the air and on the ground. This is precisely what the children of Gaza are now breathing as the Israelis drop hundreds of these deadly bombs on residential neighborhoods. There is now over 37 million tons of debris in Gaza, large sections of it filled with toxic substances.

Every war zone remains dangerous years after ceasefires. In the case of this war on Gaza, even a cessation of hostilities will not end the violence. In early November 2023, Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor estimated that the Israelis had dropped 25,000 tons of explosives on Gaza, which is the equivalent of two nuclear bombs (although, as they pointed out, Hiroshima sits on 900 square meters of land, whereas Gaza’s total square meters are 360). By the end of April 2024, Israel had dropped over 75,000 tons of bombs on Gaza, which would be the equivalent of six nuclear bombs. The United Nations estimates that it would take 14 years to clear the unexploded ordnance in Gaza. That means until 2038 people will be dying due to this Israeli bombardment.

On the mantle of the modest living room in the apartment of Anisa and Yusuf, there is a small Palestinian flag. Next to it is a small piece of shrapnel that struck and destroyed Yusuf’s left eye. There is nothing else on the mantle.

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Constant Killing: The Pentagon’s .00035% Problem

Yes, the number of deaths in Gaza in the last seven months is staggering. At least, 35,000 Gazans have reportedly perished, including significant numbers of children (and that’s without even counting the possibly 10,000 unidentified bodies still buried under the rubble that now litters that 25-mile-long stretch of land). But shocking as that might be (and it is shocking!), it begins to look almost modest when compared to the numbers of civilians slaughtered in America’s never-ending Global War on Terror that began in the wake of the 9/11 attacks and, as Nick Turse has reported in his coverage of Africa, never really ended.

In fact, the invaluable Costs of War project put the direct civilian death toll in those wars at 186,694 to 210,038 in Iraq, 46,319 in Afghanistan, 24,099 in Pakistan, and 12,690 in Yemen, among other places. And don’t forget, as that project also reports, that there could have been an estimated 3.6 to 3.8 million (yes, million!) “indirect deaths” resulting from the devastation caused by those wars, which lasted endless years – 20 alone for the Afghan one – in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Today, Nick Turse reports on how the Pentagon has largely avoided significant responsibility for civilian deaths from its never-ending air wars, not to speak of failing to compensate the innocent victims of those strikes. The civilian death toll in this country’s twenty-first-century conflicts is, in fact, a subject he’s long focused on at TomDispatch in a devastating fashion. In 2007, he was already reporting on how the U.S. military was quite literally discussing “hunting” the “enemy.” (“From the commander-in-chief to low-ranking snipers, a language of dehumanization that includes the idea of hunting humans as if they were animals has crept into our world – unnoticed and unnoted in the mainstream media.”) And when it comes to the subject of killing civilians without any significant acknowledgment or ever having to say you’re sorry, he’s never stopped. ~ Tom Engelhardt

Constant Killing: Despite Blood on Its Hands, The Pentagon Once Again Fails to Make Amends

by Nick Turse

There are constants in this world – occurrences you can count on. Sunrises and sunsets. The tides. That, day by day, people will be born and others will die.

Some of them will die in peace, but others, of course, in violence and agony.

For hundreds of years, the U.S. military has been killing people. It’s been a constant of our history. Another constant has been American military personnel killing civilians, whether Native Americans, Filipinos, Nicaraguans, Haitians, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians, Afghans, Iraqis, Syrians, Yemenis, and on and on. And there’s something else that’s gone along with those killings: a lack of accountability for them.

Late last month, the Department of Defense (DoD) released its congressionally mandated annual accounting of civilian casualties caused by U.S. military operations globally. The report is due every May 1st and, in the latest case, the Pentagon even beat that deadline by a week. There was only one small problem: it was the 2022 report. You know, the one that was supposed to be made public on May 1, 2023. And not only was that report a year late, but the 2023 edition, due May 1, 2024, has yet to be seen.

Whether that 2023 report, when it finally arrives, will say much of substance is also doubtful. In the 2022 edition, the Pentagon exonerated itself of harming noncombatants. “DoD has assessed that U.S. military operations in 2022 resulted in no civilian casualties,” reads the 12-page document. It follows hundreds of years of silence about, denials of, and willful disregard toward civilians slain purposely or accidentally by the U.S. military and a long history of failures to make amends in the rare cases where the Pentagon has admitted to killing innocents.

Moral Imperatives

“The Department recognizes that our efforts to mitigate and respond to civilian harm respond to both strategic and moral imperatives,” reads the Pentagon’s new 2022 civilian casualty report.

And its latest response to those “moral imperatives” was typical. The Defense Department reported that it had made no ex gratia payments – amends offered to civilians harmed in its operations – during 2022. That follows exactly one payment made in 2021 and zero in 2020.

Whether any payments were made in 2023 is still, of course, a mystery. I asked Lisa Lawrence, the Pentagon spokesperson who handles civilian harm issues, why the 2023 report was late and when to expect it. A return receipt shows that she read my email, but she failed to offer an answer.

Her reaction is typical of the Pentagon on the subject.

A 2020 study of post-9/11 civilian casualty incidents by the Center for Civilians in Conflict and Columbia Law School’s Human Rights Institute found that most went uninvestigated. When they did come under official scrutiny, American military witnesses were interviewed while civilians – victims, survivors, family members – were almost totally ignored, “severely compromising the effectiveness of investigations,” according to that report.

In the wake of such persistent failings, investigative reporters and human rights groups have increasingly documented America’s killing of civilians, its underreporting of noncombatant casualties, and its failures of accountability in Afghanistan, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere.

During the first 20 years of the war on terror, the U.S. conducted more than 91,000 airstrikes across seven major conflict zones and killed up to 48,308 civilians, according to a 2021 analysis by Airwars, a U.K.-based air-strike monitoring group.

Between 2013 and 2020, for example, the U.S. carried out seven separate attacks in Yemen – six drone strikes and one raid – that killed 36 members of the intermarried Al Ameri and Al Taisy families. A quarter of them were children between the ages of three months and 14 years old. The survivors have been waiting for years for an explanation as to why they were repeatedly targeted.

In 2018, Adel Al Manthari, a civil servant in the Yemeni government, and four of his cousins – all civilians – were traveling by truck when an American missile slammed into their vehicle. Three of the men were killed instantly. Another died days later in a local hospital. Al Manthari was critically injured. Complications resulting from his injuries nearly killed him in 2022. He beseeched the U.S. government to dip into the millions of dollars appropriated by Congress to compensate victims of American attacks, but they ignored his pleas. His limbs and life were eventually saved by the kindness of strangers via a crowdsourced GoFundMe campaign.

The same year that Al Manthari was maimed in Yemen, a U.S. drone strike in Somalia killed at least three, and possibly five, civilians, including 22-year-old Luul Dahir Mohamed and her 4-year-old daughter Mariam Shilow Muse. The next year, a U.S. military investigation acknowledged that a woman and child were killed in that attack but concluded that their identities might never be known. Last year, I traveled to Somalia and spoke with their relatives. For six years, the family has tried to contact the American government, including through U.S. Africa Command’s online civilian casualty reporting portal without ever receiving a reply.

In December 2023, following an investigation by The Intercept, two dozen human rights organizations – 14 Somali and 10 international groups – called on Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to compensate Luul and Mariam’s family for their deaths. This year, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Representatives Sara Jacobs (D-Calif.), Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), and Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) have also called on the Defense Department to make amends.

A 2021 investigation by New York Times reporter Azmat Khan revealed that the American air war in Iraq and Syria was marked by flawed intelligence and inaccurate targeting, resulting in the deaths of many innocents. Out of 1,311 military reports analyzed by Khan, only one cited a “possible violation” of the rules of engagement. None included a finding of wrongdoing or suggested a need for disciplinary action, while fewer than a dozen condolence payments were made. The U.S.-led coalition eventually admitted to killing 1,410 civilians during the war in Iraq and Syria. Airwars, however, puts the number at 2,024.

Several of the attacks detailed by Khan were brought to the Defense Department’s attention in 2022 but, according to their new report, the Pentagon failed to take action. Joanna Naples-Mitchell, director of the nonprofit Zomia Center’s Redress Program, which helps survivors of American air strikes submit requests for compensation, and Annie Shiel, U.S. advocacy director with the Center for Civilians in Conflict, highlighted several of these cases in a recent Just Security article.

In June 2022, for instance, the Redress Program submitted requests for amends from the Pentagon on behalf of two families in Mosul, Iraq, harmed in an April 29, 2016, air strike reportedly targeting an Islamic State militant who was unharmed in the attack. Khan reported that, instead, Ziad Kallaf Awad, a college professor, was killed and Hassan Aleiwi Muhammad Sultan, then 10 years old, was left wheelchair-bound. The Pentagon had indeed admitted that civilian casualties resulted from the strike in a 2016 press release.

In September 2022, the Redress Program also submitted ex gratia requests on behalf of six families in Mosul, all of them harmed by a June 15, 2016, air strike also investigated by Khan. Naples-Mitchel and Shiel note that Iliyas Ali Abd Ali, then running a fruit stand near the site of the attack, lost his right leg and hearing in one ear. Two brothers working in an ice cream shop were also injured, while a man standing near that shop was killed. That same year, the Pentagon did confirm that the strike had resulted in civilian casualties.

However, almost eight years after acknowledging civilian harm in those Mosul cases and almost two years after the Redress Program submitted the claims to the Defense Department, the Pentagon has yet to offer amends.

Getting to “Yes”

While the U.S. military has long been killing civilians – in massacres by ground troops, air strikes and even, in August 1945, nuclear attacks – compensating those harmed has never been a serious priority.

General John “Black Jack” Pershing did push to adopt a system to pay claims by French civilians during World War I and the military in World War II found that paying compensation for harm to civilians “had a pronounced stabilizing effect.” The modern military reparations system, however, dates only to the 1960s.

During the Vietnam War, providing “solatia” was a way for the military to offer reparations for civilian injuries or deaths caused by U.S. operations without having to admit any guilt. In 1968, the going rate for an adult life was $33. Children merited just half that.

In 1973, a B-52 Stratofortress dropped 30 tons of bombs on the Cambodian town of Neak Luong, killing hundreds of civilians and wounding hundreds more. The next of kin of those killed, according to press reports, were promised about $400 each. Considering that, in many cases, a family’s primary breadwinner had been lost, the sum was low. It was only the equivalent of about four years of earnings for a rural Cambodian. By comparison, a one-plane sortie, like the one that devastated Neak Luong, cost about $48,000. And that B-52 bomber itself then cost about $8 million. Worse yet, a recent investigation found that the survivors did not actually receive the promised $400. In the end, the value American forces placed on the dead of Neak Luong came to just $218 each.

Back then, the United States kept its low-ball payouts in Cambodia a secret. Decades later, the U.S. continues to thwart transparency and accountability when it comes to civilian lives.

In June 2023, I asked Africa Command to answer detailed questions about its law-of-war and civilian-casualty policies and requested interviews with officials versed in such matters. Despite multiple follow-ups, Courtney Dock, the command’s deputy director of public affairs, has yet to respond. This year-long silence stands in stark contrast to the Defense Department’s trumpeting of new policies and initiatives for responding to civilian harm and making amends.

In 2022, the Pentagon issued a 36-page Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan, written at the direction of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin. The plan provides a blueprint for improving how the Pentagon addresses the subject. The plan requires military personnel to consider potential harm to civilians in any air strike, ground raid, or other type of combat.

Late last year, the Defense Department also issued its long-awaited “Instruction on Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response,” which established the Pentagon’s “policies, responsibilities, and procedures for mitigating and responding to civilian harm.” The document, mandated under the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, and approved by Austin, directs the military to “acknowledge civilian harm resulting from U.S. military operations and respond to individuals and communities affected by U.S. military operations,” including “expressing condolences” and providing ex gratia payments to next of kin.

But despite $15 million allocated by Congress since 2020 to provide just such payments and despite members of Congress repeatedly calling on the Pentagon to make amends for civilian harm, it has announced just one such payment in the years since.

Naples-Mitchel and Shiel point out that the Defense Department has a projected budget of $849.8 billion for fiscal year 2025 and the $3 million set aside annually to pay for civilian casualty claims is just 0.00035% of that sum. “Yet for the civilians who have waited years for acknowledgment of the most painful day of their lives, it’s anything but small,” they write. “The military has what it needs to begin making payments and reckoning with past harms, from the policy commitment, to the funding, to the painstaking requests and documentation from civilian victims. All they have to do now is say yes.”

On May 10th, I asked Lisa Lawrence, the Pentagon spokesperson, if the U.S. would say “yes” and if not, why not.

“Thank you for reaching out,” she replied. “You can expect to hear from me as soon as I have more to offer.”

Lawrence has yet to “offer” anything.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel, Songlands (the final one in his Splinterlands series), Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power, John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II, and Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How the Wounded Return from America’s Wars: The Untold Story.

Nick Turse is the managing editor of TomDispatch and a fellow at the Type Media Center. He is the author most recently of Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead: War and Survival in South Sudan and of the bestselling Kill Anything That Moves.

Copyright 2024 Nick Turse