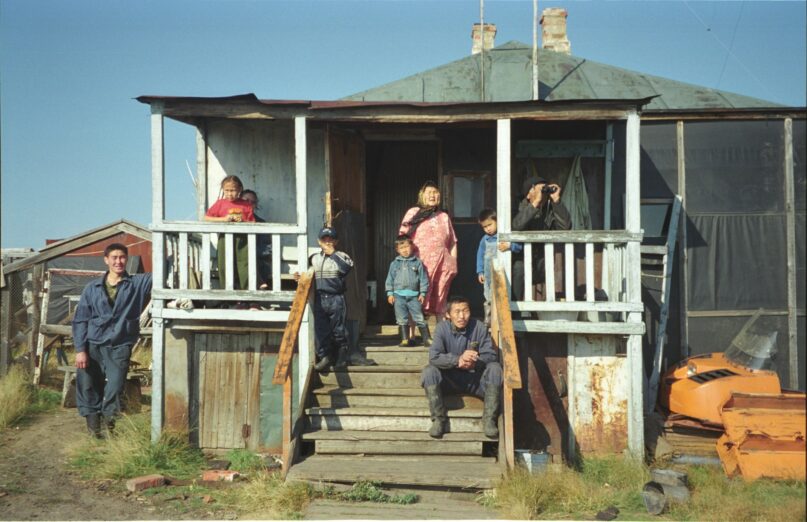

(The Conversation) — Twenty-five years ago, when I was a young anthropologist working in northern Siberia, the Indigenous hunters, fishers and trappers I lived with would often stop and solemnly offer something to the tundra. It was usually small, such as coins, buttons or unlit matches. But it was considered essential. Before departing on a hunting or fishing trip, I’d be asked if I had some change in my outer coat. If I didn’t, someone would get me some so it was handy. We left other gifts, too, such as fat from wild reindeer to be fed to the fire.

I was intrigued. Why do these things? Their answers were usually along the lines of, “We are the children of the tundra,” or “we make these sacrifices so that tundra will give us more animals to hunt next year.”

These practices are part of what I and other anthropologists call “traditional ecological knowledge.” Beliefs and traditions about the natural world are central in many Indigenous cultures around the world, bringing together what industrialized cultures think of as science, medicine, philosophy and religion.

Many academic studies have debated whether Indigenous economies and societies are more oriented than others toward conservation or ecology. Certainly the idealized stereotypes many people hold about Indigenous groups’ being “one with nature” are simplistic and potentially damaging to the groups themselves.

However, recent studies have underscored that conservationists can learn a lot from TEK about successful resource management. Some experts argue that traditional knowledge needs a role in global climate planning, because it fosters strategies that are “cost-effective, participatory and sustainable.”

Part of TEK’s success stems from how it fosters trust. This comes in many different forms: trust between community members, between people and nature, and between generations.

Defining TEK

Looking more closely at the components of TEK, the first, “tradition,” is something learned from ancestors. It’s handed down.

“Ecological” refers to relationships between living organisms and their environment. It comes from the ancient Greek word for “house,” or “dwelling.”

Finally, the earliest uses of the term “knowledge” in English refer to acknowledging or owning something, confessing something and sometimes recognizing a person’s position or title. These now-obsolete meanings emphasize relationships – an important aspect of knowledge that modern usage often overlooks but that is especially important in the context of tradition and ecology.

Combining these three definitions helps to generate a framework to understand Indigenous TEK: a strategy that encourages deference for ancestral ways of dwelling. It is not necessarily strict “laws” or “doctrine,” or simply observation of the environment.

TEK is a way of looking at the world that can help people connect the land they live on, their behavior and the behavior of the people they are connected to. Indigenous land practices are based on generations of careful and insightful observations about the environment and help define and promote “virtuous” behavior in it.

As an American suburbanite living in a remote community in Siberia, I was always learning about what was “proper” or “improper.” Numerous times people would tell me that what I or someone else had just done was a “sin” in respect to TEK. When someone’s aunt died one year, for example, community members said it happened because their nephew had killed too many wolves the previous winter.

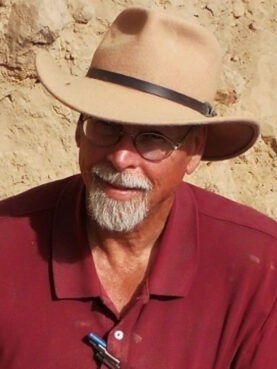

The author learning to cut up dwarf willow in the proper way for use in a summer chum, or tent, to smoke caribou meat.John Ziker, CC BY-NC-ND

Similarly, after stopping to assess the freshness of some reindeer tracks on the tundra, one hunter told me, “We let these local wild reindeer roam in midwinter so they will return next year and for future generations.” Here, TEK spells out the potential environmental impacts of greed – which, in this case, would mean overhunting.

Concepts like these are not isolated to Siberia. Much work has been done examining the parallels among ancestral systems of deference in Siberia, Amazonia, North America and other regions.

Trust and tradition

These examples illustrate how TEK is a set of systems that promote trust through encouraging deference for ancestral ways of dwelling in the world.

Moderation of self-interested behaviors requires such trust. And confidence that the environment will provide – caribou to hunt, say, or ptarmigan birds to trap – depends on the idea that people will treat the environment in a respectful manner.

Previously, I’ve studied prosociality – behavior that benefits others – in northern Siberian practices of food-sharing, child care and use of hunting lands.

These aspects of life depend on the idea that the “real” owners of the natural resources are ancestors and that they punish and reward the behaviors of the living. Such ideas are encouraged by elders and leaders, who commend virtuous and prosocial behavior while connecting negative outcomes with selfishness.

Trust is an essential component of reciprocity – exchange for mutual benefit – and prosociality. Without trust, it does not make sense to take risks in our dealings with other people. Without trust we cannot cooperate or behave in nonexploitative ways, such as protecting the environment. This is why it is advantageous for societies to monitor and punish noncooperators.

An abandoned reindeer sleigh, likely a grave, with several personal items. One is not allowed to disturb it, which would disrespect the dead, who are considered the true owners of the land.

John Ziker, CC BY-NC-ND

Put another way, minimizing one’s resource use today to make tomorrow better requires trust and mechanisms to enforce it. This is also true in larger social formations, even between nations. Groups must trust that others will not use the resources they themselves have protected or overuse their own resources.

Lessons from TEK

Today, many environmental experts are interested in incorporating learnings from Indigenous societies into climate policies. In part, this is because recent studies have shown that environmental outcomes, such as forest cover, for example, are better in Indigenous protected areas.

It also stems from growing awareness of the need to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights and sovereignty. TEK cannot be “extracted.” Outsiders need to show deference to knowledge-holders and respectfully request their perspective.

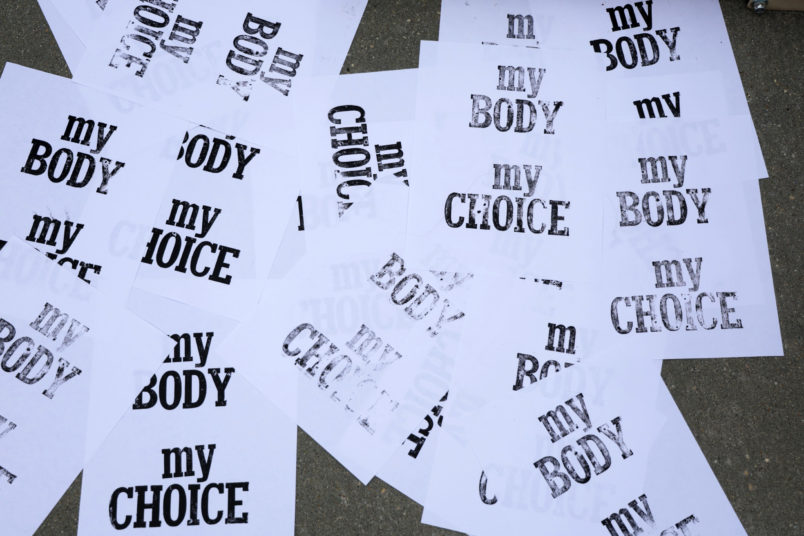

One idea societies can adopt as they combat climate change is the importance of trust – which can feel hard to come by these days. Young activist Greta Thunberg’s “Fridays for Future” initiative, for example, highlights the ethical issues of trust and responsibility between generations.

Many outdoor enthusiasts and sustainability organizations emphasize “leaving no trace.” In fact, people always leave traces, no matter how small – a fact recognized in Siberian TEK. Even footsteps compact the soil and affect plant and animal life, no matter how careful we are.

A more TEK-like – and accurate – maxim might say, “Be accountable to your descendants for the traces you leave behind.”

(John Ziker is a professor of anthropology at Boise State University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/Z55KIRHVPNA3PNGDB25B2EVJQA.webp)