Chair of board advising on legalisation of psychedelic mushrooms resigns after being accused to standing to profit from own rules

Mattha Busby

The chair of a board advising on the legalisation of psychedelic mushrooms in Oregon has resigned after being accused of standing to profit financially from the potentially $1bn industry he is helping to shape.

In 2020, after a landmark US-first vote, Oregon legalized the therapeutic use of psilocybin. But the ructions at the board could throw the whole industry into disarray.

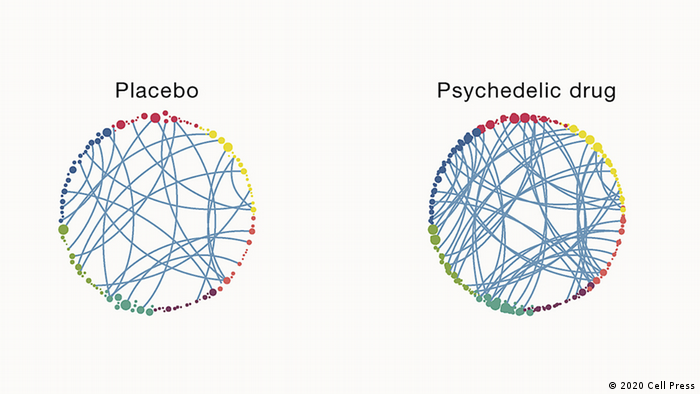

Will the magic of psychedelics transform psychiatry?

The state governor appointed an advisory board to help implement the trailblazing reforms, for rollout in January next year.

According to local media reports, however, some members of the board have allegedly announced or indicated their plans to invest in the industry.

Former chair Tom Eckert, who led the campaign to pass the psilocybin ballot, has created a company to train magic mushroom therapy facilitators.

Other members also admitted recently that they were intending to pursue business ventures, after it was agreed personal and financial conflicts of interest would be formally disclosed. The board makes non-binding recommendations to health authorities.

Responding to questions from the Guardian ahead of his resignation, Eckert – whose wife, Sheri, with whom he had campaigned for years, died in late 2020 of cardiac arrest, defended his actions.

“In many cases, our perspectives and experiences relate to industry involvement, which was known when we were appointed and is known, through our disclosures, by the board, the public, and the [Oregon health authority]. I have disclosed my projects, as have others on the board. I supported the updated policy and will continue to comply with that policy.”

He argued that individual board members use their contacts to help connect “useful people and resources’” to the board. “It is in the board’s interest to seek out and integrate the best information out there, from multiple perspectives, so that we can optimally support the Oregon health authority in building the best statewide program possible.”

But as the risk of bringing the reputation of the board into disrepute grew, he resigned. “As my life continues to change, with more relationships taking shape, I am mindful of appearances. I do not want anything to distract from the earnest work of this advisory board,” he said in a statement first reported by Marijuana Moment.

“It feels like the right time to orient my energies to the next stage of the journey. I look forward to supporting the development of Oregon’s psilocybin infrastructure in new and different rules.”

Oregon’s cautious experimentation comes as evidence grows of the beneficial effect of magic mushrooms on mental health. A handful of other US states have since moved towards rolling back psychedelic drug prohibitions and providing a legal framework for psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy.

Campaigners, experts and business people in Oregon – many of whom are passionate about the potential of psilocybin to address the country’s mental health crisis – have been tasked with helping to create the rules.

Potential conflicts of interest are, in that sense, unsurprising, say some industry sources. “This volunteer advisory board was specifically chosen because folks are involved in populating the eventual [psilocybin therapy] ecosystem with organizations,” said one company insider. “It’s a trade board in that sense.”

But David Nickles, an expert on the nascent psychedelic industry, said the “personal and professional conflicts of interest” of the chair raise significant questions.

As well as founding the firm Innertrek to train psilocybin therapists, it emerged that Eckert has also been in a personal relationship with the CEO of a company investing in the Oregon psychedelic industry. The firm, Synthesis Institute, recently bought a 124-acre property in Oregon, to host future retreats that are likely to cost thousands of dollars, as well as facilitator training.

The board has commended Synthesis for the expertise provided to them by its staff. It said Synthesis “has supported nearly 20% of our inaugural psychedelic practitioner training cohort participants” with financial scholarships.

“The chairman’s personal and professional conflicts of interest raise significant questions,” said David Nickles, an expert on the nascent psychedelic industry.

“In what situation is it appropriate for people who are crafting regulations to also profit off of the industry they are regulating? What does it mean to forge undisclosed romantic relationships across lines of industry and regulation? And, even if it’s happened before, do such practices generate or maintain a world in which we want to live?.”

Eckert told a recent board meeting that where there are potential conflicts of interest, “it makes sense for thinking of not voting on those issues”.

Oregon department of justice rules state that appointed public officials serving on a board should publicly announce any conflicts of interest, not participate in any debate on the issue and refrain from voting on it.

Eckert went on to tell the board: “There’s so many grey areas. The expertise is coming in on a lot of those subcommittees because we’re working on stuff, and I’ve been transparent about working on a training programme for example.

“Therefore, I’m interested in understanding how that can happen in all kinds of ways. So [deciding] where that line is is going to be tricky, and I’m very open to defining that a little bit more. We kind of did this on the fly early on.”

Some cannabis regulators have been accused of helping enrich friends who are already established in the industry, by raising barriers to market entry amid the so-called “green rush”. Last year in Florida, John Burnette, a developer who is married to a cannabis company CEO, was jailed for conspiring for former state representative Halsey Beshears “to keep out competitors”. Critics have argued that there is a revolving door between decision-makers and the cannabis industry.

Oregon is under particular pressure to ensure that low-income and ethnic minority communities are not shut out of the potential psilocybin economy.

A state senate committee voted last week to establish a taskforce including representatives of the indigenous community to examine barriers faced by people of colour in starting psilocybin-related businesses.

“We cannot continue the cycle of shutting out the future of medicine to certain communities and we have a rare opportunity here to prevent these inequities from being built into this system in the first place,” said state senator Wlnsvey Campos.