Afghan rescuers work through the night after deadly quake

By AFP

Published October 7, 2023

Afghan men sit in the rubble of their flattened homes in Sarbuland village in Herat province following Saturday's earthquake - Copyright AFP Genya SAVILOV

Mohsen KARIMI

Desperate rescuers scrabbled through the night searching for survivors of an earthquake that flattened homes in western Afghanistan, with the death toll of 120 expected to rise Sunday as the extent of the disaster becomes clear.

Saturday’s magnitude 6.3 quake — followed by eight strong aftershocks — jolted areas 30 kilometres (19 miles) northwest of the provincial capital of Herat, toppling swathes of rural homes and sending panicked city dwellers surging into the streets.

Herat disaster management head Mosa Ashari told AFP late Saturday there had been “about 120” fatalities reported and “more than 1,000 injured women, children, and old citizens”.

A spokesman for the national disaster authority said they expect the death toll “to rise very high”.

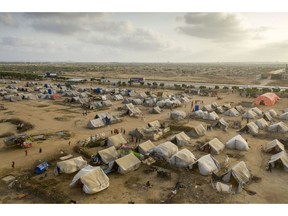

As night fell in Sarboland village of Zinda Jan district, an AFP reporter saw dozens of homes razed to the ground near the epicentre of the quakes, which shook the area for more than five hours.

Men shovelled through piles of crumbled masonry as women and children waited in the open, with gutted homes displaying personal belongings flapping in the harsh wind.

The World Health Organization (WHO) said more than 600 houses were destroyed or partially damaged across at least 12 villages in Herat province, with some 4,200 people affected.

“In the very first shake all the houses collapsed,” said 42-year-old Bashir Ahmad.

“Those who were inside the houses were buried,” he said. “There are families we have heard no news from.”

– ‘Everything turned to sand’ –

Nek Mohammad told AFP he was at work when the first quake struck at around 11:00 am (0630 GMT).

“We came home and saw that actually there was nothing left. Everything had turned to sand,” said the 32-year-old, adding that some 30 bodies had been recovered.

“So far, we have nothing. No blankets or anything else. We are here left out at night with our martyrs,” he said as darkness began to fall.

The WHO said late Saturday “the number of casualties is expected to rise as search and rescue operations are ongoing”.

In Herat city, residents fled their homes and schools, hospitals and offices evacuated when the first quake was felt. There were few reports of casualties in the metropolitan area, however.

Afghanistan is already suffering in the grip of a dire humanitarian crisis, with the widespread withdrawal of foreign aid following the Taliban’s return to power in 2021.

Herat province — home to some 1.9 million on the border with Iran — has also been hit by a years-long drought which has crippled many already hardscrabble agricultural communities.

Afghanistan is frequently hit by earthquakes, especially in the Hindu Kush mountain range, which lies near the junction of the Eurasian and Indian tectonic plates.

In June last year, more than 1,000 people were killed and tens of thousands left homeless after a 5.9-magnitude quake — the deadliest in Afghanistan in nearly a quarter of a century — struck the impoverished province of Paktika.

Death toll from strong earthquakes that shook western Afghanistan rises to over 2,000

ISLAMABAD (AP) — The death toll from strong earthquakes that shook western Afghanistan has risen to over 2,000, a Taliban government spokesman said Sunday. It's one of the deadliest earthquakes to strike the country in two decades.

A powerful magnitude-6.3 earthquake followed by strong aftershocks killed dozens of people in western Afghanistan on Saturday, the country's national disaster authority said.

But Abdul Wahid Rayan, spokesman at the Ministry of Information and Culture, said the death toll from the earthquake in Herat is higher than originally reported. About six villages have been destroyed, and hundreds of civilians have been buried under the debris, he said while calling for urgent help.

The United Nations late Saturday gave a preliminary figure of 320 dead, but later said the figure was still being verified. Local authorities gave an estimate of 100 people killed and 500 injured, according to the same update from the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

The update said 465 houses had been reported destroyed and a further 135 were damaged.

“Partners and local authorities anticipate the number of casualties to increase as search and rescue efforts continue amid reports that some people may be trapped under collapsed buildings,” the U.N. said.

Disaster authority spokesperson Mohammad Abdullah Jan said four villages in the Zenda Jan district in Herat province bore the brunt of the quake and aftershocks.

The United States Geological Survey said the quake's epicenter was about 40 kilometers (25 miles) northwest of Herat city. It was followed by three very strong aftershocks, measuring magnitude 6.3, 5.9 and 5.5, as well as lesser shocks.

At least five strong tremors struck the city around noon, Herat city resident Abdul Shakor Samadi said.

“All people are out of their homes,” Samadi said. “Houses, offices and shops are all empty and there are fears of more earthquakes. My family and I were inside our home, I felt the quake.” His family began shouting and ran outside, afraid to return indoors.

The World Health Organization in Afghanistan said it dispatched 12 ambulance cars to Zenda Jan to evacuate casualties to hospitals.

“As deaths & casualties from the earthquake continue to be reported, teams are in hospitals assisting treatment of wounded & assessing additional needs,” the U.N. agency said on X, formerly known as Twitter. “WHO-supported ambulances are transporting those affected, most of them women and children.”

Telephone connections went down in Herat, making it hard to get details from affected areas. Videos on social media showed hundreds of people in the streets outside their homes and offices in Herat city.

Herat province borders Iran. The quake also was felt in the nearby Afghan provinces of Farah and Badghis, according to local media reports.

Abdul Ghani Baradar, the Taliban-appointed deputy prime minister for economic affairs, expressed his condolences to the dead and injured in Herat and Badghis.

The Taliban urged local organizations to reach earthquake-hit areas as soon as possible to help take the injured to hospital, provide shelter for the homeless, and deliver food to survivors. They said security agencies should use all their resources and facilities to rescue people trapped under debris.

“We ask our wealthy compatriots to give any possible cooperation and help to our afflicted brothers,” the Taliban said on X.

Japan's ambassador to Afghanistan, Takashi Okada, expressed his condolences saying on the social media platform X, that he was “deeply grieved and saddened to learn the news of earthquake in Herat province.”

In June 2022, a powerful earthquake struck a rugged, mountainous region of eastern Afghanistan, flattening stone and mud-brick homes. The quake killed at least 1,000 people and injured about 1,500.

The Associated Press