Hooverville, Seattle, 1934.

Rise like Lions after slumber–

In unvanquishable number–

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you–

Ye are many — they are few.’

-Percy Bysshe Shelley

On the morning of May 9, 1934, a rejuvenated International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) struck shippers in the West Coast Ports, shutting down all of the docks from Bellingham, WA to San Diego.

Seattle’s dockers, some 1500, walked off their jobs that morning, to face an array of hostile shippers united to maintain an “open shop” and the “fink hall” on Elliott Bay, as well as hundreds of scabs reporting to work on city piers. Seattle was the coast’s second leading port, the hub of a dozen Columbia River, coastal and Puget Sound ports, second only to San Fransico in the volume of goods passing over its piers.

The long 20s had taken its toll, ILA members were few and scattered along the waterfront and it was not at all clear that the Seattle men would prevail. In the immediate days after the strike began, there were still hundreds of strikebreakers at work, and the employers clearly had plans to introduce more. The Tacoma dockers saw the situation as “shaky,” and no one wanted to see shipping continue in Elliott Bay, least of all rank-and-file longshoremen themselves; defeat in Seattle would undermine the strike everywhere.

Tacoma, a smokey industrial city, thirty miles south of Seattle, was the one port on the Pacific Coast where the ILA emerged from the twenties unscathed, the union’s single stronghold. On May 12, following a secret meeting early in the morning, the Tacoma leaders sent out a call. By 8:30 am, one thousand dockers from Tacoma (600) and Everett, as well as the smaller ports. (400), astonishingly, had assembled at the McCormick piers, there to join the Seattle strikers in sweeping the scabs from the waterfront. These strikers and their supporters, led by Tacoma’s “flying squad,” marched from pier to pier, breaking down barricades and overwhelming company guards, throwing more than a few into the Bay. When strikebreakers came off the ships, they were forced to walk through “gauntlets,” crowds of hundreds of jeering strikers shouting abuse. Those who resisted were dragged off, often beaten.

The Mayor, John Dore, sent a token contingent of police. They remained in their cars, however, or if they alighted were seen mingling with the strikers on the march up the waterfront. The Times reported many of the police sympathized with the strikers and also offered that the strikers had “a great deal of right and justice on their side.” The employers, helpless, appealed to the mayor, specifically for the National Guard. Dore, elected with labor support, insisted the Guard was not needed. The Governor, Clarence Martin, declined to offer them. At the same time, the off-shore unions, the sailors and the Masters, Mates and Pilots made the longshoremen’s strike a maritime strike. The maritime workers tied up their vessels when they reached port and joined the strike demanding higher wages, three instead of two watches, and employer recognition of their unions. On the shore, rank-and- file Teamsters joined the crowds of Seattle strikers, refusing to cross ILA picket lines. The strike became the first industry-wide strike in shipping history –on the Coast some 35,000 strong.

The strikers’ demands were for coast-wide bargaining and exclusive control of the dispatch hall. These were non-negotiable. Wages and hours were to be submitted for arbitration. The agreement would have to be to be approved by the entire membership. It would also have to be accompanied by a seamen’s strike settlement.

One striker reckoned there were others in the crowds of men that seized the waterfront that morning, “1000 unemployed came down and backed us up… they stayed until there was not one scab working on the Seattle waterfront.” And among these were the radicals of the day, “outsiders,” loggers and sailors, IWWs (Industrial Workers of the World) and Communists. As much as anything, it was the sight of these men that shook the city’s elites; it was all too reminiscent of 1919, when workers took over the city and ran it for five days. The mayor proclaimed that “a soviet of longshoremen are dictating what can be done on the waterfront.” The Seattle Times led with “Soviet Rules Seattle.”

The West Coast waterfront strike is most often remembered as the San Francisco strike, as well as for the “Albion Hall” group, communism, and Harry Bridges who emerged as the radical leader of the strike committee. And then San Francisco is remembered alongside the other great ’34 strikes, above all those of the auto-lite workers in Toledo and the Teamsters in Minneapolis.

There is a problem with this. It is not the place given to the magnificent San Francisco general strike, nor the other “pre-CIO” strikes that previewed the emergence of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Rather, it is the fact that the West Coast longshoremen’s strike was much more than simply a San Francisco event; understanding the strike that way buries another remarkable chapter in the story of 1934. In Seattle the 1934 strike became a movement; longshoremen there joined thousands of others in that glorious year, itching for a fight, one that would ultimately revolutionize workplace relations, opening the door for millions, the prologue to the story of the CIO and the great awakening of America’s industrial workers.

Seattle’s longshoremen first organized in the late nineteenth century, and from the beginning they fought long, often bloody campaigns for union recognition and a fair hiring system. In these years, almost everywhere dockers were seen as unskilled laborers, “wharf rats,” who sought work as casuals in the brutal shape-up, the daily gatherings of men, often desperate for work, at pierheads in overcrowded work “markets.” This system, as the late E.J. Hobsbawm wrote, “dominated the entire picture [of the industrial waterfront} … the casual system of hiring put foremen into something very like the position of the sub-contractor… their profits might well be made illicitly, by bribery, money lending and the like.”

Yet, if for the worker the shape-up was the jungle, man against man, it also offered everyone the chance to work, but only in the hope of finding it on the docks with backbreaking hours of grueling tasks. Stretches of unemployment, then, were interrupted with long hours of toil, day into night; “the ship must sail on time.” No wonder that waterfront strikes could be frequent, dramatic events, with each battle, lost or won, etched in the collective memory, the fights for union recognition, for abolition of the shape-up, that to be replaced by a union-controlled system, most often a union dispatch hall.

Certainly, this was the case in Seattle, where memories of the 1916 defeat (and the betrayal of San Francisco) remained bitter. At the same time. however, there were the memories of the triumphs of 1919 when these workers astounded the nation by discovering and dumping crates full of rifles bound for Russia’s white armies, saying they would rather starve than receive wages to load ships on a “mission of murder.” In 1919 the longshoremen ruled the Seattle waterfront. J.T. Doran, an IWW leader out on bail from the Atlanta Penitentiary, speaking to an overflow crowd at the longshoremen’s hall congratulated the longshoremen for killing the shape up and replacing it with an alphabetical list. “There was only one more step to contemplate,” he told the giant crowd, gathered to celebrate Eugene Debs’ birthday, that would be when a longshore cooperative Stevedore Company came into being and the “bosses were driven from the waterfront for all time.” Alas, it was not to happen, the “open-shop” employers’ response was ferocious, taking advantage of repression and the 1920 depression to force the “fink hall” back on to the dockers, a system seen by reformers as rationalization, but by workers as a return to the past. All this too was part of a workers’ memory.

American workers were unprepared for the crash of 1929 and its aftermath. The rebellions of the war years seemed distant, like another country, boom years in comparison with the cold winter of 1933, when fifteen million were unemployed and millions more worked part time “Grim poverty stalks throughout our land…It embitters the present and darkens the future.” said President Roosevelt.

The percentage of American workers in unions had collapsed by 1933. The post- war Red Scare kicked off a decade of aggressive anti-union corporate policy – policies that vacillated between the big stick and the carrot of welfare capitalism-had taken their toll. The depression of 1920-21, “the forgotten depression” (production fell by 32.5%, a decline second only to the Great Depression, unemployment approached a 12%) had undermined the gains of the war years, including those on Seattle’s waterfront.

Strikes were few, mostly lost. The steel workers had been battered in their massive strike in 1919. The railway shopmen lost in their 1922 nationwide strike. The results for the United Mine Workers, long the backbone of the American labor movement, were catastrophic. The union in the central coalfields -Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana -was impoverished and factionalized by decade’s end. There was no union at all in the southern fields -from West Virginia to Alabama. The Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, heirs to the militant Western Federation of Miners, disintegrated. Its 1927 convention was attended by fewer than a dozen members. Seattle’s shipyards, the heart of the rebellion of 1919, fueled no longer by war, were shuttered, victims of a conspiracy of the owners, the government and compliant East Coast unions, a political deindustrialization in a union town. The metal workers scattered.

On the West Coast waterfront, by 1929, the ILA virtually ceased to exist; the shipowners had asserted all but complete control over wages and conditions. Seattle’s dockers worked out of a company hall, as did Portland and San Pedro longshoremen. There were no members in San Francisco. There dockers shaped up each morning, gathering at dawn at piers along the Embarcadero to be hired, or not, most often one day at a time. Tacoma alone weathered the storm, the ILA and its union dispatch hall intact.

There were 30,000 workers unemployed in Seattle and King County in 1931, with their dependents, more than a third of the population, another third had only partial employment. Gone were the queues of ships waiting for unloading in the Bay, as shipping declined and Seattle fell behind San Francisco. Light manufacturing continued, but on a scale much reduced; workers faced wage-cuts and short-time. The city became synonymous with its “houseboat menace” and its “Hoovervilles,” and “hobo jungles,” the largest of which was made up of thousands of shacks on the premises of the closed Skinner and Eddy shipyards on the east waterway of the Duwamish River. Its inhabitants were called by the city’s “respectables,” “a scrap heap of castoff men.” These men, however, did their best to maintain order, as well as dignity, electing a mayor and a town council. Most were unemployed lumberjacks, fishermen, miners and seamen.

Only the Teamsters Union prospered. It was led by the young Dave Beck, a laundry driver who made his name with the shakedown, while opening the door to thugs and racketeers, and offering the employers collaboration, an alternative to strikes and Communists. In the fifties, he would become the International President of the Teamsters, following that a prisoner on McNeil Island federal penitentiary, convicted of tax evasion. But by 1926, Beck and his supporters dominated the Seattle Central Labor Council (SCLC). In 1934 he quickly moved to call off the rank-and-file strike supporting truckers.

The first “rumblings of discontent” came in 1931. The Seattle unemployed formed the Unemployed Citizens League, “the first self-help organization in the United States,” according to the historian Irving Bernstein. The initiative came from Carl Brannin and Hulet Well’s of the Seattle Labor College, an institution founded in 1922 in the last days of the Seattle rebellion. Wells, a socialist, had been President of Seattle’s Central Labor Council during the war. He was in prison in 1919 on McNeil Island for having opposed conscription. The two men opposed the idea of charitable handouts; instead, they launched the League. It quickly grew to 12,000. In a year it had 80,000 members in the state of Washington. It became ubiquitous in King County, its presence a seedbed of radicalism. The League’s Seattle waterfront branch was instrumental in reviving the ILA, whose members had begun trickling back, bypassing the Communists’ Marine Workers Industrial Union.

The revival of the union also reflected the passage of the New Deal National Recovery Act that created the National Recovery Administration to work with industry and labor to increase employment. The Act’s Section 7-A provided workers the choice of their own representatives to bargain collectively with employers.

The employers were stunned by “Gauntlet Day.” WES, the Washington Employers of Seattle, appealed to the mayor as well as the governor, demanding assurances that the strikebreakers be protected – until then there would be no work on the waterfront. Mayor Dore wrote the Governor that, “to avoid bloodshed…it was absolutely essential that we have troops here immediately.” The Governor refused but wrote to the President requesting federal assistance. Meanwhile WES organized strike committees, recruited strikebreakers, housed them and assessed the shippers, the stevedores and the various dock business; by May 16 they had collected $40,000. They reiterated their stand; no union, no coastwide bargaining and no union dispatch hall. It was revealed only later that Beck was secretly meeting with them. On May 11, he overruled the eight Seattle Teamsters locals, ordering the truckers back to work –to no avail, the rank-and-file, “voted with their feet,” at least for the time being.

The shippers, in the aftermath of Gauntlet Day, having no protection, retreated, the harbor was effectively closed, though sporadic fighting continued, indeed it might be more accurate to see the waterfront as a battleground in an eighty-three-day war. There was a “riot” in early June at the Alaska Building in downtown Seattle where strikebreakers were being hired. At the same time, violence was likely whenever strikers met sheriff’s deputies, company guards, suspected strikebreakers, or vigilantes. The American Legion claimed to have 1,000 members. Steven Watson, a sheriff’s deputy was shot and killed, as was a sailor and a dock foreman

San Francisco, nevertheless, remained the center of attention throughout the strike, negotiations held there, even with strikers (also in San Pedro) in the first days still fighting to clear the Embarcadero of hundreds of strikebreakers. It was where the Australian-born Harry Bridges and his allies took control of the ILA Coast District strike committee, a committee they would control negotiations right until the settlement in July.

By mid-May negotiations were already stalled. Roosevelt responded by sending Assistant Secretary of Labor Edward McGrady to California from Washington DC. The employers, however, continued to refuse to recognize a coastwide ILA – they agreed only to recognize the San Francisco local – and the union held firm on its demands for a union hiring hall. The administration then requested that Joseph Ryan, ILA “International” President, intervene. Ryan, the flamboyant, gun-toting New York mobster who ran the ILA, was known for silk suits and diamond rings. He arrived on May 24, where he piled on with the employers and Beck, who greeted him in San Francisco, where they agreed to an employers’ offer – the “May 28 Offer” for San Francisco. Ryan claimed it would “enable the ILA to get a strong foothold on the entire Pacific Coast.” At once, however, it was clear that the rank and file everywhere would reject this; word came down from Seattle that it had no chance. “Absolutely, nothing doing” responded the union’s Secretary, Dewey Bennett. “We stick with every local on the Coast,”

Nevertheless, the next day Ryan and Beck flew up to the Northwest, where in Tacoma, Ryan was met with overwhelming opposition. In Seattle, accompanied again by Beck, the two argued that the agreement was “best for Seattle,”’ lest San Francisco and/or San Pedro take advantage. The response was the same. Ryan was continually interrupted with among other things, “Hey Ryan, you’ve still got time to catch the Empire Builder [the train} for New York.” McGrady suspended negotiations.

The strikers had little in terms financial resources, certainly nothing to match the millions of the shippers and their allies. Still, they had community support. The SCLC took on the tasks of relief and support. Soup kitchens were set up for individuals and commissaries for families. Farmers responded with fruit and vegetables. Restaurants offered free meals. The fisherman’s union donated salmon. Most longshoremen could sleep at home, but unions donated space for sailors to sleep. Women, wives and others, organized an Auxiliary. Solidarity ruled. There is no evidence of the systematic use of black strikebreakers, though of course this still might have happened. Ottilie Markholt reported that there were forty black ILA members among the strikers. Black cooks and waiters helped in the kitchens. Frank Jenkins, a second-generation black longshoreman, was working on the Seattle docks in 1934, as did his younger brother. The Japanese unions too offered support. And there were rallies, large and small. On June 19 Charles Cutright, a veteran of 1919, addressing 10,000 strikers and supporters at the Municipal Auditorium, called for a general strike, setting off a “wild” roar of support.

There were frequent threats of a general strike – in Portland, in Tacoma, in the coastal towns. There, the towns, Longview, Kelso, Raymond, Aberdeen, and Hoquiam, were radical outposts, still home to a sizeable number of IWWs and Communists. The closest one came to a general strike was in Longview-Kelso where in response to the violence is Seattle 600 loggers, sawmill workers, warehouse workers and pulp mill workers walked out The Central Labor Council, representing 3,500 workers, wired the Northwest Strike Committee, “We are prepared to use whatever means are necessary to protect members of the ILA.” Bridges said he felt at home in Aberdeen. In Seattle, the ILA requested the SCLC call a strike, but it was blocked by Beck and his allies. Beck said he feared the union leaders would lose control.

Seattle in 1934 remained the “gateway” to Alaska, and from the start, the employers and the press raised the specter of economic ruin, above all for the fisheries, including the canneries of Bristol Bay and the Inside Passage. At the same time, Seattle’s fishing fleet was locked down in the Fisherman’s Terminal. The press led with forecasts of starvation for the population of the Pan Handle – to a skeptical rank and file in Seattle – condemning what it called an “embargo of food and medicine for the Alaskans.” The longshoremen claimed to see industrial parts and equipment, also crates of beer.

This became a crisis of sorts for the strikers. They were divided, the public appeared to be turning against them. The Joint Northwest Strike Committee – led by Paddy Morris of Tacoma – had been organized to maintain solidarity amongst the Northwest ports. It was composed of representatives of all the striking local unions in Puget Sound, as well as other Washington ports and Portland, then too the seamen and supporting organizations and individuals. An unexpected consequence, it also became a gathering place and meeting ground for rank-and-file strikers from an array of union and places. After much argument, the Committee ultimately decided to release vessels to alleviate the “emergency”; on June 8 the ILA signed the off again on again “Alaska Agreement” with the shippers, in what the strikers hailed as a victory.

It provided for the closed shop, union hiring hall, the six-hour day and retroactive wages to be arbitrated. The employers also acceded to demands of the seagoing unions. And it was agreed that the Alaskan ships would be loaded in Tacoma, understanding that no effort would be made by employers to open Commencement Bay by force. Longshoremen from Pacific Northwest ports would travel to Tacoma, where they would be dispatched from the union hall to work the ships. A half of the wages would be paid directly to the men, one-fourth was sent to their local strike committee, and another fourth went to the joint Northwest Strike Committee, the rest to San Francisco.

In early June, Charles Smith replaced Dore as Seattle’s Mayor. Smith was the former President of the King County (Seattle) Republicans with the support of the WES and the Chamber of Commerce, and having made it clear that he intended to open the port, if necessary, with violence. Smith announced that he intended to break the strike. Smith took personal pride in the introduction of tear gas and machine guns on a large scale. The police were armed with the latest “riot control weapons.” Sherriff Claude Bannick deputized 500 new men. Smith became known as “machine gun Smith.” In preparation, the shippers organized a small army of private guards.

The violence continued on all fronts. On June 20, Smith sent his forces to Smith Cove where 600 strikers assembled under the Garfield Street Bridge. They had piled junk on to the railroad tracks, which in addition they covered with grease and oil. All telephone lines were cut, and cars and trucks were turned away. On arrival, the truckers and railroad engineers refused to move freight, saying the conditions were too dangerous. The Strike Committee threatened to withdraw from the Alaska agreement. There were many casualties.

On June 30 a contingent of strikers traveled to north Point Wells, investigating a rumor that strikebreakers at the Standard Oil docks were about to sail a tanker into the Sound that night. They were attacked by guards with axe handles, then a shot rang out. Striker Shelvy Daffron, a leader of the Seattle longshoremen, was shot. He died in a Seattle hospital. 1,000 longshoremen and seamen attended his funeral, then marched four abreast to the Lakeview Cemetery.

Nevertheless, the strike was far from broken, and the waterfront remained to the end a battleground. The final conflict would come in July, at Smith Cove on the northern end of the waterfront. There, on July 17, police, the sheriff’s deputies and the shippers with their strikebreakers and guards massed, preventing strikers trying to get through the gates to evict the strikebreakers. That evening, 3000 strikers and sympathizers attended a rally sponsored by the Joint Northwest Strike Committee at the Civic Auditorium. The following morning, flying squads from Tacoma, Everett and Bellingham, led a thousand Seattle strikers and sympathizers against police lines. Police hurled tear gas bombs at the charging men. The strikers retreated but came back a second time holding handkerchiefs to cover their faces. They broke through the police lines, and encamped on the railroad tracks in front of the dock gates. The next day, the police raided the Marine Workers Industrial Union and the Communist party halls, as well as the Workers Bookstore and the offices of the Voice of Action, the Communist party paper.

On July 19, Seattle Police Chief George Howard argued with Mayor Smith over the use of force against strikers; he resigned. Smith took command. At 5 am, the Tacoma, Everett, Aberdeen and Bellingham reinforcements marched in semi-military formation into the strikers’ enclave in front of the pier gate. At 6:45 am the mayor gave the order to drive pickets from the Cove. Longshoremen in the front ranks yelled, “Come on men, hold your ground.” Police Captain George Comstock shouted to this army from the top of the bridge that spanned the Cove, “Al right, let ‘er go. Tear gas rained down from the bridge onto the pickers. Strikers with gloves picked up cannisters and tossed them back. The police then on foot attacked the strikers, shooting tear gas and wielding riot sticks against those who tried to hold their ground. A few pickets, not yet affected by the gas, threw stones at the advancing police; resistance was met by police clubs. Olaf Helland, a sailors’ union striker, fell mortally wounded, hit in the head by an unexploded gas grenade. More casualties, many, on both sides. In fifteen minutes, the police had chased pickets from the gates to the railroad tracks where a last stand was made. Then mounted police drove the men up the slopes of Queen Ann Hill, where they scattered. The battle had ended. Mayor Smith and the Chamber of Commerce President Alferd Lundin congratulated each other.

The outcome of the strike, in the most immediate sense, then, was at best inconclusive, worse a defeat. On August 3, the Communists’ paper, Voice of Action, led, “Betrayed by the top leadership of the American Federation of Labor, sold out by the government arbitration board, terrorized by the police, the longshoremen returned to work, the eighty-third day of the coast wide strike They returned to the same hiring hall system which they had when they struck, to the same open shop method, at the same wage scale.” William Crocker, the San Francisco banker was jubilant, “Labor is licked.”

In many ways they were. In Tacoma, with pickets still on the docks, Paddy Morris, no radical, confessed, “The labor unions are tired of the fight…The return of the Teamsters has weakened our position…We don’t feel the fight is over – it has just begun. This is merely a truce. The ship owners have lined up all capital on their side, and this is a battle between Labor and Capital.” In San Fransisco, Bridges, appealing to the seamen, said much the same. “I think the longshoreman is ready to break tomorrow. They have had enough of it…The ship owners have got us backed up… we are trying to back up step by step… instead of turning around and running…I don’t think that they will last. They have had enough of it. They have their families to support. They are discouraged by the Teamsters going back to work, they didn’t get enough support from the council… I disagree with our officials in lots of things they have done.”

The longshoremen had opposed arbitration; they had little faith in the National Longshoremen’s Board when hearings were held in San Francisco, Seattle, Portland and San Pedro in September. In October the Board issued its award: it fixed the basic wage rate at $.95 an hour, $1.40 for overtime. It established a six-hour day, thirty-hour work week. Saturdays, Sunday and legal holidays were made overtime days.

On the crucial issue of the hiring hall, the Board ruled: “The hiring of all longshoremen shall be through hiring halls maintained and operated jointly.” But “the dispatcher shall be selected by the International Longshoremen’s Association.” Longshoremen were to be dispatched “without favoritism or discrimination” because of “union or non-union membership.” Victory. The union would select the dispatcher!

The men, however, knew already they had won. They realized it well before the Board’s October findings. The strike had empowered them, it had illuminated their courage and power. The longshoremen had undertaken a campaign that would utterly transform working conditions and relations on the West Coast. The unions were made more democratic; racism was challenged; their chief weapons, solidarity and direct action.

In the aftermath of the strike, they fought incessantly; they detached themselves from the New York gangsters who ran the ILA. and they founded a new union, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). They affiliated with the industrial unions in the Congress of Industrial Organizations. They came to see themselves – far from the “wharf rats” of before – rather as “The Lords of the Docks”, proclaiming, immodestly, “We are the most militant and organized group of workers the world has ever seen.” All this, they did, from the bottom up.

The struggle, then, had just begun. In the next years there would be hundreds of strikes on these docks, and countless disputes. Here is one account:

On “…every dock the gang elected from among themselves a so-called gang or dock steward… There were endless disputes, some resulting in “job actions” on the part of the workers or quick strikes (“quickies”) localized to one dock…

“Suddenly in the midst of unloading a ship, the longshore gang would walk off, causing the stubborn employer sailing delay, considerable additional expense, and general irritation…

“The employer then called the union hiring hall for another gang, which came promptly enough, but as likely as not pulled another “quicky” an hour later; and so on till the employer yielded to, say, a demand that the sling load be made two or three thousand instead of four thousand pounds.”

The strike empowered the longshoremen, and along with them a generation of working people. This raises many issues for the historian: what were its origins? was it a Communist strike? why the employers hysteria? how to explain the Board’s findings? could the workers have won more? is this of any relevance today?

These are questions well beyond the scope of this brief celebration of the strike and the longshoremen who led it. In any case, there are no easy answers here. The federal government, for example, had its own agenda, and this was not workers’ power. It was, however, more far-seeing than the industrialists, who, in any event, opposed it all, that is, the unions, the New Deal, the reorganization of American capitalism. The Roosevelt administration believed that the chaos of the industrial system had to be reined in, regulated. It believed it could succeed in doing this, in alliance, when possible, with the conservative leaders of the AFL, if necessary, then the CIO. It understood that the strike was not in fact a “Communist plot,” also that “smashing” the strike might have unintended consequences.

The uprising in Seattle and Northwest strikes, needs featuring in this history; it drew on long memories, on the tradition of direct action, mass movements, immigrant strikes, labor wars and rank-and-file rebellions that have repeatedly exploded the conservatism and complaisance of this country, above all, in the Seattle in the great strike of 1919.

The strike was not a Communist strike, a handful of party members notwithstanding, although cults of Bridges, the union and leadership have distorted this history, exaggerating triumphs and disguising failings. And neither were the other strikes of 1934 revolutionary strikes, even those led by revolutionaries. The bolshevized socialism of the thirties rarely was successful in penetrating the rank and file of the workers’ movements and the new unions, never in the long run. The rise of Dave Beck and his Teamsters brought home again the problem of the AFL and its leadership, undermining everything that was decent in Seattle’s (and everyone’s) labor movement, leaving a stain that rank-and-file workers contend with to this day.

The longshoremen’s strike was, however, a radical strike, a very radical strike, a mass strike led by rank-and-file workers, relying, as they so often have, on themselves alone. It was, in this sense, a festival of the oppressed. It showed the courage of workers, of ordinary people, it was an example of the power of workers, their ability to organize, their capacity for struggle, the power of solidarity.

My thanks go to Zack Pattin, Aaron Goings and the late Ron Magden

.jpg?ext=.jpg) (Image: Kazatomprom)

(Image: Kazatomprom) (Image: Rosatom)

(Image: Rosatom)

.jpg?ext=.jpg) Palisades (Holtec)

Palisades (Holtec).jpg?ext=.jpg) The LVR-15 research reactor (Image: CVŘ)

The LVR-15 research reactor (Image: CVŘ) How the STEP building may look (Image: UKAEA)

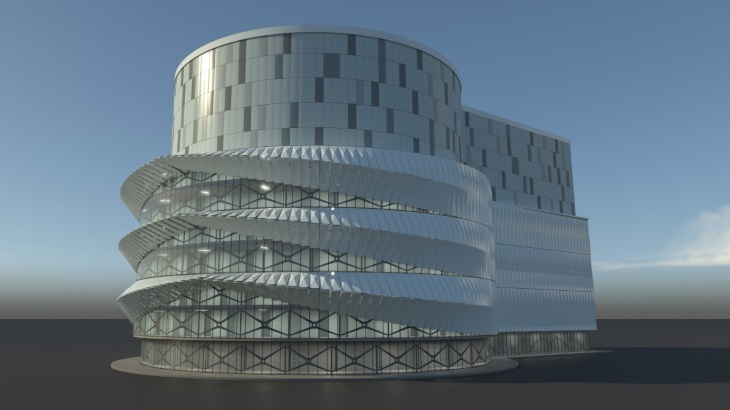

How the STEP building may look (Image: UKAEA)