Today, Situationist ideas are popular, and certain key terms of the SI critique are so apt to current realities, they strike many as self-evident. To the young, urban, wired and socially astute of today, terms like “dérive”, “psychogeography”, “separation”, “spectacle” and “détournement” not only ring familiar on first hearing, but they (or close equivalents) are in many cases already in active everyday use. Artists, cultural activists, architects, urbanists, art historians, critical theorists, sociologists, media designers, experimental film makers, advertisers, PR agents[1] and military strategists[2] all have reason to know parts of the situationist project. And the “art” parts of that project in particular have recently enjoyed the cachet of a serious radical chic in art and design spheres. How could they fail to? The story of the SI presents us the picture of a hip, smart, truly bohemian avant-garde in still recent times, culturally closer and easier to identify with for many than what happened in Zurich or Berlin or Paris in the 1910’s and 20’s. And thanks to increasing up-take of the situationist “thing” among academic theorists and art historians, the movement behind this chic has now also been institutionally legitimated, and authorized as a “real” avant-garde. So, if you liked Dada and Surrealism, you’ll love the SI.

The cultural “arrival” of the SI is not in question. But what is noticeable about this popularity are its limits, and how similarly so many sectors of the cultural mind draw these limits in their framing of the SI phenomenon. What most reliably falls outside this framing, of course, is the true scale and seriousness of the situationists’ radical commitment.

From the beginning,” writes Debord in 1971, near the end of the situationist project, “the situationist project was a revolutionary program”[3].

Now, you can call a given cultural phenomenon “revolutionary”, or “radical”, and keep doing so for a long time without ever having to either affirm or to repudiate what those words really must mean when applied to some of the most interesting cases. The ambiloquence of how the label “avant-garde” gets applied in arts discourse centers precisely on the difference between referring to a formal or conceptual radicality, revolutionary in artworld and artmarket terms exclusively, and referring to a concrete, social-political radicality, the revolutionary human commitment to transforming everyday life by altering the conditions that determine how it is organized. When considering the SI, it is artificial to try separating a cultural-intellectual radicality off from the social-political radicality. A biasing of the former over the latter is out of balance, and ignores the project’s defining trajectory and the manifest consistency and coherence of its guiding principles.

If you like the Situationist International, in other words, you like a group of cultural actors who were certain of “the impossibility of the continuation of the functioning of capitalism”[4]. Who were dedicated to provoking a crisis in society through sustained attack on the false “idea of happiness”[5] that keeps people participating in the losing game of capital. Who were organized, literally and tactically, to assist where possible in fomenting real revolution, and worked hard to push the situation that presented itself in May ’68 over the edge into a permanent revolution in which

autonomous collective action would triumph over hierarchical domination and passive compliance in every sector of governance, industry and society.

WHAT CAN THE REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT DO NOW?

EVERYTHING

WHAT BECOMES OF IT IN THE HANDS OF THE PARTIES AND UNIONS?

NOTHING

WHAT DOES IT WANT? REALIZATION OF THE CLASSLESS SOCIETY THROUGH THE POWER OF THE WORKERS’ COUNCILS

council for the maintenance of the occupations[6]

Launch Trajectory of the Situationist Project

The situationists emerged out of a small but potent ferment of avant-gardist activity in post-WWII Paris. In fact the SI was the third stage in a noisy scramble to reestablish the project of radical avant-gardism after the decline of Surrealism, whose practices the horror of international fascism and industrial genocide had rendered ridiculous and irrelevant. The first stage of this scramble was the founding of Lettrism, by a Romanian Jewish immigrant, Isidore Isou, who arrived in Paris in 1945, at what must have seemed an impossibly inappropriate time for babbling nonsense poetry in the cafés to shock the bourgeoisie. But the goal Isou had set was a serious one, and as Lettrism took root it became clear that radical critique and condemnation of contemporary society was no less relevant after the war than it had been before it, especially in view of the survival of the underlying political economy that had made the war possible in the first place. In particular Lettrism aimed to get back to a purer strand of avant-gardist negativity represented by Dada, before the critical force of that negativity was diluted in the magical thinking and obscurantism of later Surrealism.

Focusing on sound poetry, collage and experimental film-making, the Lettrists took aim at the values of bourgeois society using the media and imagery of pop culture and channeling the energy of youth rebellion. By the early 1950’s Lettrism had attracted a number of young poets and artists who understood the challenge of resuming Dada-styled radicalism in the unlikely context of a rising peace-time prosperity. A number of them, Serge Berna, Gil Wolman and Guy Debord included, took this challenge seriously enough to begin applying the Dada critique to Lettrism itself, ultimately judging it guilty of merely wanting to carve out its own safe niche within the commodity art economy. In 1952 these and other “ultra-Lettrists” broke away to form the “Lettrist International” (LI), re-radicalizing the movement Isou had started and excluding him along with the rest of the backward faction. The LI commenced a sustained period of self-critique, carried out particularly in the mimeographed pages of their newsletter Potlatch[7] and of the Belgian review Les Lèvres Nues[8], where they recommitted themselves to the Dada principle of repudiating artistic practice in favor of direct action within the sphere of everyday life. They reasserted the difference between formal radicalism and social radicalism, and dedicated themselves to searching out a mode of cultural engagement capable of remaining undistracted in its focus on the concrete goal of changing life.

Poetry has exhausted the last of its formal prestige. Beyond aesthetics it resides wholly in the power of men over their own adventures. Poetry is read on people’s faces. So it is urgent to create new faces. Poetry is in the form of cities. So we will construct stunning new ones. The new beauty will be SITUATIONAL, that is provisional and lived. (Potlatch 23; translations mine)

The most elegant games of the intellect mean nothing to us. Political economy, love and urbanism are the means we must control for the resolution of a problem that is first of all ethical.

Nothing can excuse life from being absolutely impassioning.

We know how this is done. (Potlatch 11)

Urbanism and architecture, which had featured more peripherally in the programs of earlier avant-garde movements[9], quickly emerged as a primary focus for the LI. It answered the urgency they felt to eliminate gaps between creative action and everyday life. It realized an intuition implicit in the Dada call to overcome art, namely that as artistic action moved to escape its own limits, it would spread over into every other sector of life as a possible field of recuperative engagement. At the time the ultra-Lettrists were rededicating themselves to engaging the practice of life directly, urbanism was the biggest genre-label they knew for integrating the arts and crafts in a superior constructive activity. At the start, “Unitary Urbanism” had meant precisely urbanism as an all-container for artistic production; “the use of all arts and techniques as means contributing to the composition of a unified milieu” (SI, 22). It was a directive with roots in the arts and crafts movement, in nouveau style and early Bauhaus. A totality of the crafts of ambience and of the furnishing of everyday life[10], a creative, resistant functionalism, an “Imaginist Bauhaus”[11] in Jorn’s hopeful phrase. But this rogue constructivism came blended with a romantic spirit left over from surrealism. Its dream was to claim the city as canvas for a new kind of art and a new kind of life, a new dimensionality of art and life occupying the full environmental surround with the spirit and artifacts of creative exploration and play. In the language of Ivan Chtcheglov’s seminal “Formulary for a New Urbanism”:

Architecture is the simplest means of articulating time and space, of modulating reality, of engendering dreams….Architecture will be a means of modifying present conceptions of time and space. It will be a means of knowledge and a means of action. …experimentation with patterns of behavior with cities specifically established for this purpose….buildings charged with evocative power, symbolic edifices representing desires, forces, events past, present and to come. (SI 2)

Engaging the city as a poetic project came naturally to the founders of the SI, in that it was largely what they were doing already. As chronicled in Debord and Jorn’s lyrical détournement work Mémoires[12], the first years of the LI were a left-bank bohemian romance which those who lived it would never forget. It was the concrete, uncompromising adolescent romance that would anchor a twenty-year run of engaged utopian radicalism. And Paris was both the setting of this romance and the most glamorous co-star. The city mattered because living mattered, and those who would become the Situationists sensed, more minutely than most, how the possibilities of that living were conditioned by the urban surround.

It was not as professionals that they approached these questions, but as jobless delinquents, poets, lovers, cynics and drunks. The dérive, a mode of observational drifting countless artists have by now integrated into their practice[13], and countless planning and urban studies programs[14] into their pedagogies, began as little more than dead time in the stumble of vagrants from bar to bar. And psychogeography, the art-science whose very name seems to promise a permanent human refutation of alienation in the urban field, emerged out of no more experience or authority than the standard dissatisfaction of youth. “We are bored in the city!” reads the first sentence of Chtcheglov’s “Formulary”, and thus of the whole project of a Situationist urbanism. The accomplishment of the SI as a movement was that they never got over that boredom, and they never ceased to hold the organization of urban society responsible.

Their blaming the city for their boredom led to their analysis of separation as a condition imposed by urbanism, and to their understanding of urbanism as a branch of the spectacle mobilized to enforce separation. From the days of their first intentional dérives, they had had this critique of the late-modernist urbanism they saw unfolding around them. As they mapped out the ambience potentials around chance encounters or surprise events, they saw a systematic dismantling of all chances as Paris succumbed to its modernisation a la Corbusier[15]. In the negative space of the most intensely lived years of their lives, they discerned the outlines of a society moving programmatically to eliminate the conditions of that intensity. As the collective authors concluded in their article, “The Skyscrapers by the Roots”, in issue 5 of Potlatch:

So that’s the programme: life cut up forever into closed-off sectors, into surveilled societies; the end of possibilities for insurrection and encounter; automatic resignation. (Potlatch 22)

And it was with this observation that the SI committed itself to urbanism as suitable program for a revolutionary avant-garde.

The Negativity of Situationist UrbanismIf you are researching your possibilities in the field of architecture and urban design, or looking for new, more human ways of engaging the urban field as an artist or architect, situationist writings and practices have a lot to offer. The situationists’ brand of urbanism brings inspiring concepts of play, chance, ambiance, encounter, mobility and freedom to the design of the urban field. Consider some of the “Rational Embellishments to the City of Paris” published in issue 23 of Potlatch (October, 1955)[16]:

By a particular arrangement of fire-escapes and the installation of railings where needed open the roofs of Paris to promenading.

Or,

Equip the street lamps of every street with light switches, letting the public control the lighting.

Or, on the largest scale that this creative planning would assume for the Situationists, Constant’s vast envisioning of a rhizomic network urbanity called New Babylon. Constant was, with Asger Jorn, from the COBRA/Imaginist Bauhaus contingent present at the founding of the SI. The only situationist structure ever built was the highly modular and transformable gypsy camp he designed for a community in Alba, Italy, on the occasion of the SI’s inception (Sadler 37). But the countless drawings, maps and models created to visualize this New Babylon—more idea of life than city, more city than theory of urban form—constitute the most palpable expression of what an urban society (dis-)organized along situationist lines would look like. Of course, it is only one possible version, but Constant’s vision captures a lot. It seeks to host in an infinitely modifiable urban infrastructure, completely superimposed as a new layer over existing cities and terrain, scaffolding for a movable feast of psychogeographical experiences and lifestyles, based on those the situationists were tasting on dérive in various places, and recording in a number of psychogeographical maps and reports they published in their journals.[17] Without Constant’s New Babylon, these maps and reports and a handful of lyrical suggestions would be the only existing proof-of-concept of situationist urbanism. With it, the situationist idea becomes one of the grand utopian city visions of modern times.[18]

An important number of architects and urban planning offices have gravitated to the range of concepts and challenges presented by the situationist project. Sadler makes a good list of them in the conclusion to his famous study, The Situationist City, many considered authoritative:

…the situationist fallout scattered so widely, and so thinly: onto Team 10, onto Ralph Rumney’s “Palace” exhibition at the ICA in 1959; onto Italian radical design; onto the environments and happenings movement; onto Archigram, thence to the Architectural Association in London, and so onto, for example, Richard Rogers, Bernard Tschumi, Nigel Coates, and the NATO Group; and even into the art-historical syllabus itself, through the agency of British situationist-turned-historian T.J.Clark. (Sadler 163)

I could add others such as Lars Spuybroek[19], Chora[20] under Raoul Bunschoten, the An Architektur[21] collective in Berlin, Stephen Read’s Spacelab[22] at Delft, Stalker[23] in Rome and Park Fiction in Hamburg[24]. At the same time, a seemingly constantly regenerated pool of artists, designers and students every year is drawn into some fascination with this group of colorful, anti-establishment hipsters out to change the world. If it is a serious option within the real professional arrangements of a spatial design or planning career, who wouldn’t want to devote themselves to changing the world, using the latest practices and techniques of psychogeography, defined by Debord as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals” (SI 5)? What self-respecting architect or urbanist would not insist this is what they were doing already?

But much of the steady or fad-like interest we see people taking in the SI’s ideas can only be maintained in polite society in ignorance of the greater bulk of situationist activity and production, which does not manifest in drawings or maps or scale models. For the situationists were nothing if not consistent in their repudiations, and just as surely as they repudiated art as inadequate to the revolution they were after, ceasing to make hypergraphic collage or discrepant film works, they eventually repudiated creative urbanist art and city design for the same reasons. However, this fact has been even less observed by fans and scholars of the movement than the fact of their repudiation of art. This is important to establish, that just as it is relevant for interested artists today to know that situationist thinking would probably have rejected the kind of art they themselves are doing, partly under situationist inspiration, it should be obvious to any interested architects or urbanists that situationist urban theory, especially in its late phase, is antithetical to design activity, where the fundamental conditions of political-economy supporting that activity are not overthrown.

It is important to see that when the situationists (lettrists at the time) took urbanism into their avant-garde practice, they did so on what was for them a trajectory out of poetry and into revolutionary action. You can see this chronicled in the successive issues of their journals, and in the composition of the group from year to year, but it is already conscious from early on. After the SI was founded, as Constant was evolving New Babylon, Debord was focusing on making contacts with other groups and theorists (one example, Socialisme ou Barbarie), broadening the SI analysis and sharpening the edge of its revolutionary theory[25]. At a certain point, as this analysis of current conditions advanced, doing urbanism became seen as in fundamental conflict with the project of changing life, and it was repudiated.

The concepts and practices of Unitary Urbanism had been central for the situationists already from the first years of the Lettrist International. The pages of Potlach from 1954 onward give coherent and eloquent testimony to the birth and establishment of this as an avant-garde program, just as the first five issues of L’Internationale Situationniste document the phase of the situationist project under Constant and characterized by his constructive idealism. Constant’s New Babylon was developed from the gypsy camp of 1956 onward as the constructive dimension of the situationist project. In1958 Constant and Debord established the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism in Amsterdam. This Amsterdam Declaration lays out a program for the Bureau; item 4 establishes urbanism within the project: “The minimum programme of the S.I. is the experimentation with complete decors, which should extend to a unitary urbanism, and research into new behaviors in relation to these decors” (IS #2, IS 63). And in item five we get a statement of how urbanist activity is to be understood: “Unitary urbanism is defined in the complex and permanent activity which, consciously, recreates man’s environment according to the most evolved conceptions in all fields. (my italics)”

Unitary Urbanism was featured in similar terms in what is perhaps the key founding document of the SI, Debord’s “Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action” (1957). But there the project of urbanism is framed not with reference to the profession, but very consistently within the legacy of avant-garde activity and self-criticism in the Dada tradition. The move into urbanism is explained as the latest in a generational process of clarification and radicalization that must be constantly renewed. In Debord’s document, the possible role of urban critique and creativity within the situationist project comes only after a lengthy and exhaustive accounting of the group’s attitude and position in regards to all important previous phases of the avant-garde, and a recommitting to the radical refusal of artistic practice. Architecture and urbanism here appear as the answer to avant-garde critique of lettrist art practice, as the domain “outside” art, finally to be claimed by artists in the name of transforming everyday life.

But, as Constant and Debord saw it, this focus was not singular. Rather it figures as one side of a binary between which the real core enigmatic aim of the situationist project, the “construction of situations” can be pursued. Urbanism is important because of the purchase it gives on the construction of something much more ephemeral, and closer to the radical human possibilities of transformation. The mission Debord ascribes to this urbanism is formulated in the foundational Report as “systematic intervention based on the complex factors of two components in perpetual interaction: “the material environment of life and the behaviors which it gives rise to and which radically transform it” (SI 22)[26]. And, as the actual tasks to be performed by a radical urbanist practice, he identifies the two main modes of psychogeographical research: “active observation of present-day urban agglomerations and development of hypotheses on the structure of a situationist city” (23).

A critical urbanist practice on this model was undertaken for the effectiveness it promised in creating ambiances and in preparing the conditions for undefined “situations” that might contain a transformative social potential. But, at least for Debord, the true value and potential of this practice must be seen as still unproven. Psychogeographical research and the “unitary” design program it promises to inform are for Debord in 1957 still at the stage of testing their hypotheses:

The progress of psychogeography depends to a great extent on the statistical extension of its methods of observation, but above all on experimentation by means of concrete interventions in urbanism. Before this stage is attained we cannot be certain of the objective truth of the initial psychogeographical findings. But even if these findings should turn out to be false, they would still be false solutions to what is nevertheless a real problem.

The problem (call it alienation, or spectacle-market capitalism) was never in doubt for the situationists, but within a couple of years the results of their experimenting and hypothesizing, together with the natural evolution of their (principally Debord’s) critical analysis, it became obvious that positive, constructive unitary urbanism was itself just such a false solution. As a result of debates with Debord, Constant quit the SI in 1960. Attila Kotanyi joined in the same year and replaced Constant as head of the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism, which was moved from Amsterdam to Brussels and commenced an intensive critique of the profession and of prior SI activities. Issue 6 of the Internationale Situationniste is cumulatively the most concerted document of situationist anti-urbanist critique. It reclaims the term unitary urbanism(which I will spell with a lower-case “u”), and rededicates it to radical, revolutionary critique. It represents the mature stage of psychogeographic theory where that term comes to mean not so much a heuristic to support design practice as a comprehensive political-economic theory. The term “psychogeographic materialism” even appears around this time, to express this refocusing, and to project the notion of a theory of urbanism that concludes the untenability of urbanist practice. Kotanyi and Raoul Vaneigem begin from this point in framing their new “Elementary Program of the Bureau of Unitary Urbanism” in 1961. It is the first sentence of that text that declares: “L’urbanisme n’existe pas”. “Urbanism does not exist, it is merely an ideology in Marx’s sense” (IS 214).

In an editorial note to that decisive 6th issue, the collective authors show the retrospective consistency they see in repudiating constructive urbanism, referring back to the 3rd issue to quote themselves saying “The situationists have always said, ‘unitary urbanism is not a doctrine of urbanism but a critique of urbanism’” (IS 203). The editorial committee argues that even a very critical design practice at this stage of political-economic development remains a hopelessly separated activity, whatever avant-garde intentions it may express. It can be radical in its conception, but because of its containment within a spectacular economy (whether of professional planning or experimental art) it will remain unable to act on “real life”. Real life as a value, as a sphere, however vaguely that must be defined, is for everyone by definition the total, the “unity” sought in “unitary urbanism”. But the search to restore that unity to practice and to life has no prospects within this separation, and it is the fundamental economy of urbanism to produce separation. This is perhaps the central tenet of the new basic program Kotanyi and Vaneigem write for the Bureau in its late phase:

The whole of urban planning can be understood only as a society’s field of publicity-propaganda, i.e. as the organization of participation in something in which it is impossible to participate.[27]

Over the SI’s first five years, their understanding of urbanism had deepened, and their analysis of conditioning factors in the environment shifted from formal and aesthetic levels to the level of spectacle formation and control, the level at which the effective conditioning is happening. They became interested in the city, less as an interrupted funhouse, and more as a behavior of capital, And in this analysis they came to see urbanism as an equal arm of the spectacle, with information media the other. In the “Elementary Program” it read:

Modern capitalism, which organizes the reduction of all social life to a spectacle, is incapable of presenting any spectacle other than that of our own alienation. Its urbanistic dream is its masterpiece.

In Raoul Vaneigem’s “Commentaries Against Urbanism” in the same issue, it read:

Urbanism and information are complementary in capitalist and “anti-capitalist” societies; they organize the silence. (IS 232)

This insight, into thespectacular function of urban design, ushered in a new phase of the situationist project, considered its maturity. Debord dates this phase from 1962, and calls it the second, the first corresponding to years 1957-62 and “centered on the overcoming of art”[28]. In another perspective, though, the pre-SI years from 1952-1957, would be seen as the first phase, during which art and design activities continued, though under serious self-criticism. The mature phase fulfills intuitions and determinations from the previous two phases, but distinguishes itself from them in asserting definitively that urbanism too, like art, has proven itself unable to fulfill the SI’s basic ambition as an avant-garde movement – to change life, radically understood – and that it must therefore be set aside in favor of revolutionary theory and direct action. This phase culminated in May ’68 when this next stage of hypothesizing could be put to the test.

For the method of experimental utopia to truly correspond to its project, it must obviously embrace the totality, that is, its implementation will not lead to a “new urbanism”, but to a new usage of life, a new revolutionary praxis. (IS 205).

In consciousness of the nature of spectacle-consumer society, the core focus of situationist concern shifted from the side of “situation” that corresponds to the concrete built surround, to the side that corresponds to the behaviors situations produce and that produce situations. With the maturing of this perspective on radical practice, the notion itself of a situation jumps orbits to a higher state. The vague body of potentials lurking around a blind corner in an unknown neighborhood concentrate all their promise and appeal into the specific objective promise of revolutionary potential. Situation as in: “Governor, we have a situation”. A moment in which exceptional events or insurrectionary behavior have opened a concrete chance for radical change.

With this view of their mission, urbanist thinking and production assume new job descriptions and new assignments. Where the unitary urbanist was once expected to carry out “active observation of present-day urban agglomerations and development of hypotheses on the structure of a situationist city” (23), consistent practice now would require slightly different things. For example, observation of contemporary revolutionary struggles and their modes of organization around the world, and production of theory and propaganda as practical action shaping a revolutionary situation locally or abroad. Kotanyi and Vaneigem assert this propaganda function as a task of the new Bureau: “distanciation from the urban spectacle”:

Our first task is to permit people to cease identifying with the environment and model behaviors…We must support the diffusion of distrust toward those airy colorful kindergartens that constitute, in the East as in the West, the new dormitory towns. Only awakening will pose the question of a conscious construction of the urban milieu. (IS 215).

Understanding urbanism’s role in an urbanity leveraged endemically against autonomous human community and the self-management of voluntary and democratic groups, depends on understanding how urbanism functions in production of the spectacle. For urbanism is not just a branch of spectacular communication (communication without response), it is also the soil out of which the spectacle is born. Debord and the 3rd phase unitary urbanists viewed the city as representing a particular phase in the historical process of capitalization. This phase corresponds approximately to Lefebvre’s stage of “urban society”[29], characterized by “complete urbanization”. At this stage, industrialization reaches a limit in extension (geographic advance) that it will then surpass intensively (as capitalization). But the process itself of urbanization has generated contradictions which it requires a new level of production to resolve. This contradiction is the one produced by the coming together of ever-larger populations in an ultimately exploitative process whose functioning effectively requires separation, among society and within individuals. When it reaches this stage, capitalist urbanization begins generating the spectacle automatically, as an attendant need of continued production. And, however abstract and ethereal the spectacle may appear as a force, the physical reality of urbanisation’s contradictions will always require that the separation be operated also at the concrete level of the organization of territory:

167 This sociey which eliminates geographical distance reproduces distance internally as spectacular separation.

…

171 If all the technical forces of capitalism must be understood as tools for the making of separations, in the case of urbanism we are dealing with the equipment at the basis of these technical forces, with the treatment of the ground that suits their deployment.

172 Urbanism is the modern fulfillment of the uninterrupted task which safeguards class power: the preservation of the atomization of workers who had been dangerously brought together by urban conditions of production… (Spectacle)

With this analysis, to be against urbanism means being against preserving “the atomization of workers…brought together by urban conditions of production”. For the situationists it also meant, more directly, committing to act against that atomization, theoretically and practically, wherever it worked. Theoretically, Debord’s Society of the Spectacle and Vaneigem’s more accessible Treatise on Living for the Use of the Young Generation sought to explain the mechanisms of separation and the basic strategies of resistance. And practically the group began tolook to the possibilities of direct action as the best expression of its urban analysis and urban theory, which by this point had become indistinguishable from revolutionary theory.

The situationists had long been observing resistance struggles around the world, especially Algeria, which was in the thick of labyrinthine urban warfare between rebels and French colonists. Similarly they watched the race struggles in the United States, and looked for moments where the rage at racial oppressed might connect with rage at the oppression of everyday life. Issue 10 of Internationale Situationniste featured a long piece entitled “The Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Market Economy”, with a press photo from the looting and burning in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. The caption read: “Critique de l’urbanisme (Supermarket a Los Angeles, August 1965)”.

So, when in 1968 students and then workers began to stand up and occupy the schools and factories that ran their lives, members of the SI worked hard to make sure that the exceptional situation would be understood as one of wide open possibilities for overturning the status quo and reorganizing society (urbanized, industrialized, capitalized) through spontaneous and consensual creation. In Paris, they manned the presses and the day and night debate forum of the Council for the Maintenance of the Occupations, from which the action taken by Sorbonne students was fanning out into the social fabric of France.[30] Regionally, they networked as they could to encourage further occupations and the radicalization of demands. And internationally they reached out to every affiliated group they could think of, many of them involved in dramatic times also in their countries, in the hopes that the spark would catch, and spread world-wide.

For a short time, the situationist lived the possibility, rare in history, of putting the hypotheses of an anarchic revolutionary utopianism to the test, and with it, the potentials of a “situationist” urban theory at both its most critical and its most constructive. For, with a certain threshold crossed, the design of cities and the making of art could once again become honorable activities, in the context of a dis-alienated society of radical self-determination, organized around democratic work-place councils.

Failing its revolutionary potentials, May ’68 would be the culmination of the situationist project, and the great last test of its urban theory. A final phase of the movement, from ‘68 and to 1972 when Debord disbanded it, was spent interpreting the results. This task history continues.

Of all the affairs we participate in, with or without interest, the groping search for a new way of life is the only aspect still impassioning. Aesthetic and other disciplines have proved blatantly inadequate in this regard and merit the greatest detachment. (Debord, “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography, 1955; SI 5)

Pouvoir au conseils ouvriers! (Power to the workers’ councils! Street graffiti attributed to the Situationist Internationale, Paris, May ’68.)

Situationist Journals

Potlatch: Bulletin d’information du groupe français de l’Internationale lettrise 1954-1957, 1996.Paris: Éditions Allia.

Les Lèvres nues 1954/1958, 1998. Paris: Éditions Allia.

Internationale Situationniste 1958-1969, 1997. Paris: Librairie Artheme Fayard.

Knabb, Ken (ed., tr.) 1981.Situationist International Anthology. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Online Sources

Situationist International Text Library: http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/all/

Situationist International Online: http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/

Notbored.org: http://www.notbored.org/SI.html

Single-Author Works

Chtcheglov, Ivan2006. Écrits retrouvés. Paris: Éditions Allia.

Debord, Guy 2004. Mémoires. Structures portantes d’Asger Jorn. Paris: Éditions Allia.

Debord, Guy1983. Society of the Spectacle. Detroit: Black & Red. Also, free online at http://library.nothingness.org/articles/SI/en/pub_contents/4

Debord, Guy1992. Commentary on the Society of the Spectacle. Paris: Gallimard.

Jorn, Asger 2001(1957). Pour la forme: Ébauche d’une méthodologie des arts.Paris: Éditions Allia.

Vaneigem, Raoul 1992 (1967). Traité du savoir-vivre a l’usage des jeunes génerations. Paris: Gallimard. Also, free online at http://arikel.free.fr/aides/vaneigem/

Vienet, René 1992 (1968). Enragés and Situationists in the Occupation Movement, France, May ’68Tr RichardParry, Helen Potter. New York: Autonomedia.

About the SI

Baumeister, Biene & Zwi Negator 2005.Situationistiche Revolutionstheorie, Stuttgart: Schmetterling Verlag.

Dumontier, Pascal 1990. Les situationnistes et mai ’68 : théories et pratique de la révolution (1966-1972). Paris: Gérard Lebovici (coll. Champs libres).

Donné, Boris 2004. Pour Mémoires: un essai d’élucidation des mémoires de Guy Debord. Paris: Éditions Allia.

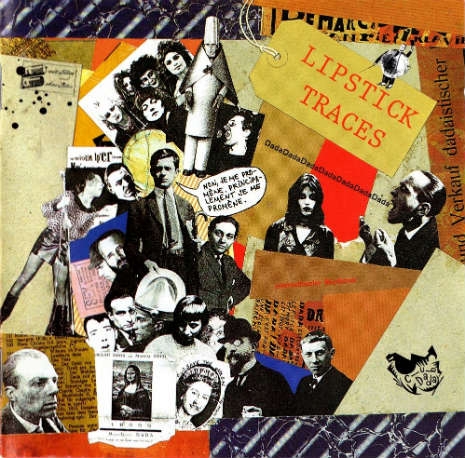

Marcus, Greil1990. Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sadler, Simon 1999. The Situationist City. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wigley, Mark 1999. Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyperarchitecture of Desire. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

- situationists at goteborg

- WHAT CAN THE REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT DO NOW? EVERYTHING WHAT BECOMES OF IT IN THE HANDS OF THE PARTIES AND UNIONS? NOTHING WHAT DOES IT WANT? REALIZATION OF THE CLASSLESS SOCIETY THROUGH THE POWER OF THE WORKERS’ COUNCILS council for the maintenance of the occupations

- poverty of student life

- may 68 street scene

- lettrist call

- geopolitics of hibernation

- constant new babylon

- constant labyrinth

- claude lorraine

[[3]]“L’étage suivante”, Internationale Situationniste No. 7, Paris: 1962, p. 47. Also, IS, p. 287.