The history of and experiences from previous pandemics give us important information about how to handle today’s corona pandemic.

«Nearly everything we know about pandemics emergency preparedness and how the measures affect society long-term comes from the Spanish flu experience», says May-Brith Ohman Nielsen. The photo is from Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C in 1918. (Photo: Harris & Ewing / Wikipedia)KILDEN GENDER RESEARCH NEWS MAGAZINE

Thursday 30. july 2020 -

Covid-19 is not the first pandemic in human history, nor will it be the last. But have pandemics affected women and men differently through the ages? And can we learn anything about why and how, so we better understand what goes on today?

«Pandemics are a magnifying glass that sheds light on social conditions, gender included,» says May-Britt Ohman Nielsen, professor of history at the University of Agder.

Tuberculosis is one example of a disease that has affected women and men differently at different times, according to May-Brith Ohman Nielsen. (Photo: UiA)

Case history into consideration

Nielsen works with the history of medicine, illness, health, and epidemics. She studies how pandemics affect women and men differently and uses examples from cholera and tuberculosis.

«Infectious diseases affect women and men differently, primarily because they have different roles and functions through history,» she says.

Tuberculosis has had different effects on the sexes throughout the ages, according to Nielsen.

«The disease is still active and widespread in large parts of the world, and people live with it for a while,» she explains.

«The disease spreads through droplet infection, and the source is often difficult to trace because the illness develops slowly. Infected persons may have been ill for a long time before the symptoms occur, and the infected or their surroundings become aware of them.»

Men spread infection, women nursed

Men were often the first to be infected during pandemics such as cholera and tuberculosis because they travelled more, as sailors, tradesmen, and soldiers, Nielsen explains.

«Consequently, men spread the diseases in larger circles, as they travelled, were infected, and brought the diseases home with them.»

At home, the infected men were often nursed by their sisters, mothers, wives, and daughters, who then became infected.

«It was not unusual that the women in the family felt pressure to take care of the men regardless of whether they wanted to. Those who brought home the money took precedence in the family regardless of how dangerous the disease might have been,» says Nielsen.

«Traditionally, women have carried the burden of care and taken on the emotional responsibility. This makes up the greatest difference between men and women regarding illnesses and pandemics. Women take care of children, spouses, and parents.»

Guilt and shame

To get infected with cholera, you have to swallow the bacteria. It infects through contact, but primarily through the drinking water. When the source of infection could not be identified, people came up with other theories about how the disease was spread, according to Nielsen. These theories were also gendered.

«For instance, many believed that cholera was a punishment from God. And there were different ideas about why women and men were punished», she says.

«When it came to the men, they were often thought to be punished for drunkenness, whereas women were infected because they were promiscuously dressed and had bad morals.»

The fact that tuberculosis could be connected to hygiene also affected men and women differently. The illness brought along strict requirements for the housewife in terms of infection control measures and hygiene, Nielsen explains.

«If a family was infected, the woman of the house might be considered a bad housewife who failed to keep a clean home. Tuberculosis resulted in a lot of shame,» she says.

«The men were forbidden to spit, while the women were required to clean.»

«Like covid-19, the plague spread as a result of increased globalisation», says Ole Georg Moseng. (Photo: USN)

Plagues and globalisation

Ole Georg Moseng, professor of history at University of South-Eastern Norway, has studied the history of plagues. He also draws parallels to today’s epidemic.

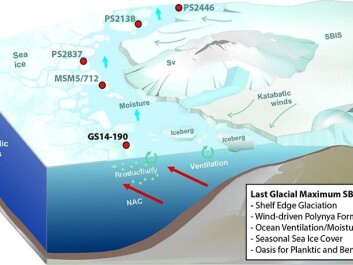

«Like covid-19, the plague spread through increased globalisation,» he says.

«The plague has always been a part of human history. The oldest recorded case is from 3 900 BCE, and the last major epidemic is from 2017 in Madagascar. Plague outbreaks occur in several countries across the world every single year.»

In other words, the plague still affects us. But as a pandemic, we are primarily talking about three major waves, Moseng explains. The earliest recorded pandemic occurred in the early Middle Ages between c. 540 and 750 CE, the second began in 1346 and lasted until 1722, whereas the third pandemic wave occurred in the late 1800s.

«The first outbreak started in the cities that were the centres of civilisation: Rome, Carthage, Constantinople and in the vicinity of Alexandria,» says Moseng.

During the second and largest outbreak, which began in Crimea in 1346 and is referred to as the Black Death, the plague spread to large parts of Europe through travelling tradesmen and explorers. Repeated outbreaks in Western Europe occurred up until the early 1700s.

«We may, therefore, assume that men spread of the plague, particularly as tradesmen,» he says.

«The third plague pandemic broke out in India and China in the late nineteenth century and spread all over the world during the course of two decades. In Europe, it caused a number of minor outbreaks of plague around the year 1900.»

«Women most sorely affected»

Moseng explains that the plague bacteria is transmitted to humans via fleas from wild rodents. And during the Black Death it particularly spread through the black rat, which eats grain and grain products, but is more or less extinct in Europe today.

«We have relatively good data on gender differences in how the plague affected people from the 1600s onwards. It seems like women were most affected by the plague», says Moseng. But recent studies of the Black Death in the 1340s indicate that this was also the case back then.

The black rat is one possible explanation to why more women than men had the plague.

«Women stayed more inside the houses than men did. Rats lived in the houses, and may have given the plague on to women,» he says.

«In addition, women held traditional caring functions, which made them more exposed to infection. They had the main responsibility for the children and the elderly in the family, and their job was to care for those who were ill.»

Moseng states that another consequence of the plague, more indirectly gendered,is how it contributed to the collapse of the feudal system.

«The Black Death resulted in an enormous and persistent decline in the population in Europe, which led to poorer conditions for women in the long term,» he says.

The land rent went down and fewer people paid taxes. The feudal lords, that is, the big farmers, kings and the church, lost power. The workers’ wages went up, and the petty farmers had more money to spend.

«As a result, the land-owning aristocracy’s economic, political and social hegemony was weakened, which laid the foundation for the growth of the bourgeoisie. In bourgeois society, women had less power than in the agricultural feudal society,» says Moseng.

«Feudal society was hierarchical, but women were nevertheless more equal to men in their life as a housewife on a farm», he says.

«The wife on the farm had a lot of power, whereas bourgeois norms ensured that the men were given a more distinct leader position within the family.»

More men died of the Spanish flu

«The Spanish flu came to Norway in 1918, and led to the death of 15 000 Norwegians, or 0.6 per cent of the population. Approximately half of the Norwegian population were probably infected by the disease», according to Svenn-Erik Mamelund who is a demographer and pandemics researcher at Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet).

Mamelund explains that the flu pandemic affected Norway in four waves: Two in 1918, one in 1919 and a ‘echo-wave’ in 1920.

There is not enough data on gender differences in mortality rates globally. But Mamelund says that it is likely that a few more men than women died of the Spanish flu, as was the case in Norway. People around the age of thirty became sicker and died more often.

«Especially during summer 1918, more men than women were infected. Men had broader and more frequent contact with others through work and social activities than women.»

Svenn-Erik Mamelund believes that the fact that young people in fertile age now find themselves in a society in lockdown may cause further decrease in the number of childbirths. (Photo: OsloMet)

Young adults particularly affected

The Spanish flu affected primarily young adults between the age of twenty and forty. That is when women are most fertile.

«This is partly why there was a dramatic decline in the birth rate in 1919, and nine months after the Spanish flu was at a peak in the autumn of 1918. People were hesitant to have sex, because they feared being infected or because they were already ill. The mortality rate among pregnant women increased, especially during the late stages of pregnancy. The number of miscarriages also increased,» Mamelund explains.

«Many men and women lost their spouse to the flu. Approximately 4 800 people were widowed in 1918–19, and the Marriage Act required at least one year of mourning before one was allowed to re-marry. Unless a woman was already pregnant when she lost her husband to the Spanish flu, she was by law denied a new pregnancy before she had re-married. Of course some women did conceive outside of marriage, but this was not common.»

Mamelund maintains that the baby boom in Norway in 1920 is a result of the Spanish flu rather than the end of the First World War, as many historians have claimed.

«The 1920 baby boom is the greatest in Norway, only beaten by the one following the Second World War in 1946. Many people postponed marriage and childbirths until the epidemic was over in 1919. Also, Norway did not participate in the First World War,» he says.

Mamelund draws parallels to the current pandemic. The fertility rate in Norway is in decline due to the corona epidemic, according to an article in the Norwegian newspaper DN.

«The fertility rate has been in decline for a long time in Norway, and the fact that young fertile people now find themselves in a society in lockdown may cause further decrease in the number of childbirths», he says.

Widows were badly affected

Coming back to the Spanish flu, Mamelund maintains that women who lost their husbands were probably affected harder than men who became widowers.

«At that time there was no such thing as widow’s pension and social security programs, and the women lost the family’s breadwinner,» he says.

«I would like to do more research on what happened with the bereaved during this pandemic. What coping strategies did they have? What happened to all the orphans? Did women apply different strategies than men? I believe they did.»

Mamelund gives one example: A woman from the Norwegian midlands was left behind with two small children when her husband and two other children died of the Spanish flu.

She did not re-marry; instead, she divided her land, kept an acre and sold the rest. She built a house on her part of the land and bought a cow, a goat and hens for the money she got from the sale. Her daughters worked on farms in their spare time, so that they could get enough healthy food.

Resulted in widow’s pension

The Spanish flu changed the society, also for women. In 1919, the Labour Party introduced social security benefits for single mothers and widows in the capitol, according to Mamelund.

«The reason may have been the consequences the Spanish flu had for women who lost their husbands to the disease and were left behind with small children.»

Many have referred to the Spanish flu as the forgotten pandemic, he says.

«But forgotten by whom? The doctors? Historians? The history of the Spanish flu is no victory narrative and it has no winners. I think that many people wanted to forget. They wanted to leave the pandemic behind and move on.»

Here, too, there are gender perspectives, according to Mamelund.

«Nancy Bristow, an American professor of history and pandemic researcher, has studied the Spanish flu by going through diaries, letters, photographs, and other ethnographic and archive material. According to her, the doctors – who were primarily men – wanted to forget the Spanish flu altogether. They felt that they had lost the battle against the disease, and they felt powerless and disappointed.»

«For the nurses, however, it was the other way around. They felt useful during the pandemic, when they had cared for and comforted sick and dying patients. Even though there was no cure, nursing, food and care were still necessary and the nurses had been essential in this work.»

The idea of anti-bac is not new

According to Ole Georg Moseng at University of Oslo, there are some clear common features between previous pandemics and covid-19, for instance when it comes to how we fight it.

«Actions like isolation of the ill, lockdown, travel restrictions, embargo on trade, quarantines and use of facemasks were also used to fight the plague in the 16th and 17th centuries», he explains.

Antibacterial hand gel is nothing new, says Mamelund. 7000 people in Norway died from tuberculosis each year between the years 1890 and 1910. The disease was fought without medicines, but with hand wash, hygiene, social distancing and public enlightenment.

«The nurses played an important role. They travelled around and educated people. They talked about the same things as the Institute of Public Health goes on about today: keep your distance, don’t drink from your neighbour’s cup and don’t ‘spit on the floor’.»

Read: “Women’s historical contributions are still ignored”

We can learn from the Spanish flu

May-Britt Ohman Nielsen at the University of Agder also see parallels.

«Today public health workers are particularly exposed to infection. This was also the case for those who treated patients with tuberculosis», she says.

«Especially the nurses, who stayed by the bedsides in the tuberculosis sanatoriums, were infected. And they were primarily women.»

But the infection also hit places with mostly men, according to Nielsen.

«In mines, boarding schools, the military, and especially the front line during the First World War, diseases spread rapidly and a large number of men were infected by tuberculosis and the Spanish flu.»

The history and experiences from previous pandemics gives us important information about how to handle today’s corona pandemic.

«The Spanish flu is the great learning model. Nearly everything we know about pandemic emergency preparedness and how the society is affected long-term, comes from this experience. How do isolation and closed down workplaces and schools affect relations between people?» she says.

«And in what ways do these measures change society in the long run? Here we can learn a lot from history.»

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro