Early mammal with remarkably precise bite

Researchers investigate teeth of a small carnivorous mammal that are almost 150 million years old

UNIVERSITY OF BONN

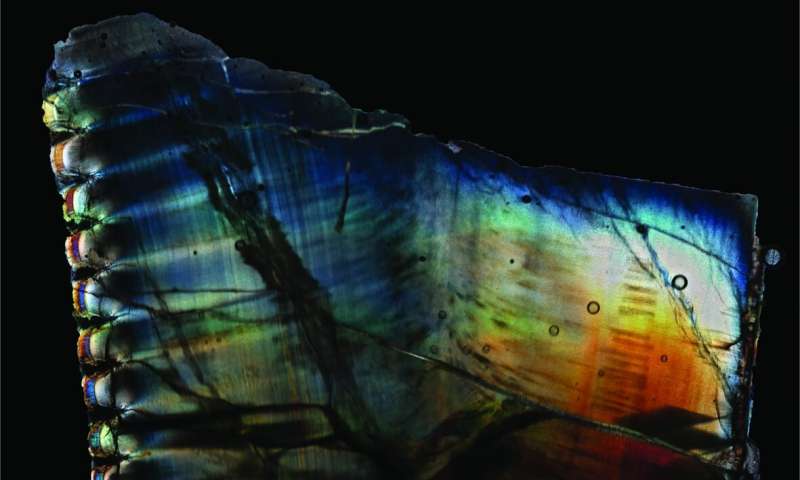

IMAGE: THE INVESTIGATED DENTITION OF P. FRUITAENSIS. THE UPPER MOLARS (M2, M3) ARE OFFSET FROM THE LOWER ONES (M2, M3). THIS CAUSES THE CUSPS TO INTERLOCK IN A WAY THAT CREATES... view more

CREDIT: © THOMAS MARTIN, KAI R. K. JÄGER / UNIVERSITY OF BONN

Paleontologists at the University of Bonn (Germany) have succeeded in reconstructing the chewing motion of an early mammal that lived almost 150 million years ago. This showed that its teeth worked extremely precisely and surprisingly efficiently. Yet it is possible that this very aspect turned out to be a disadvantage in the course of evolution. The study is published in the journal "Scientific Reports".

At just twenty centimeters long, the least weasel is considered the world's smallest carnivore alive today. The mammal that researchers at the University of Bonn have now studied is unlikely to have been any bigger. However, the species to which it belongs has long been extinct: Priacodon fruitaensis (the scientific name) lived almost 150 million years ago, at a time when dinosaurs dominated the animal world and the triumph of mammals was still to come.

In their study, the paleontologists from the Institute for Geosciences at the University of Bonn analyzed parts of the upper and lower jaw bones of a fossil specimen. More precisely: its cheek teeth (molars). Because experts can tell a lot from these, not only about the animal's diet, but also about its position in the family tree. In P. fruitaensis, each molar is barely larger than one millimeter. This means that most of their secrets remain hidden from the unarmed eye.

The researchers from Bonn therefore used a special tomography method to produce high-resolution three-dimensional images of the teeth. They then analyzed these micro-CT images using various tools, including special software that was co-developed at the Bonn-based institute. "Until now, it was unclear exactly how the teeth in the upper and lower jaws fit together," explains Prof. Thomas Martin, who holds the chair of paleontology at the University of Bonn. "We have now been able to answer that question."

How did creatures chew 150 million years ago?

The upper and lower jaws each contain several molars. In the predecessors of mammals, molar 1 of the upper jaw would bite down precisely on molar 1 of the lower jaw when chewing. In more developed mammals, however, the rows of teeth are shifted against each other. Molar 1 at the top therefore hits exactly between molar 1 and molar 2 when biting down, so that it comes into contact with two molars instead of one. But how were things in the early mammal P. fruitaensis?

"We compared both options on the computer," explains Kai Jäger, who wrote his doctoral thesis in Thomas Martin's research group. "This showed that the animal bit down like a modern mammal." The researchers simulated the entire chewing motion for both alternatives. In the more original version, the contact between the upper and lower jaws would have been too small for the animals to crush the food efficiently. This is different with the "more modern" alternative: In this case, the cutting edges of the molars slid past each other when chewing, like the blades of pinking shears that children use today for arts and crafts.

Its dentition therefore must have made it easy for P. fruitaensis to cut the flesh of its prey. However, the animal was probably not a pure carnivore: Its molars have cone-shaped elevations, similar to the peaks of a mountain. "Such cusps are particularly useful for perforating and crushing insect carapaces," says Jäger. "They are therefore also found in today's insectivores." However, the combination of carnivore and insectivore teeth is probably unique in this form.

The cusps are also noticeable in other ways: They are practically the same size in all molars. This made the dentition extremely precise and efficient. However, these advantages came at a price: Small changes in the structure of the cusps would probably have dramatically worsened the chewing performance. "This potentially made it more difficult for the dental apparatus to evolve," Jäger says.

This type of dentition has in fact survived almost unchanged in certain lineages of evolutionary history over a period of 80 million years. At some point, however, its owners became extinct - perhaps because their teeth could not adapt to changing food conditions.

###

Publication: Kai R. K. Jäger, Richard L. Cifelli & Thomas Martin: Molar occlusion and jaw roll in early crown mammals; Scientific Reports, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-79159-4

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Credit: CC0 Public Domain

Credit: National Research Council of Science & Technology

Credit: National Research Council of Science & Technology