Cecilia Jamasmie | September 23, 2022

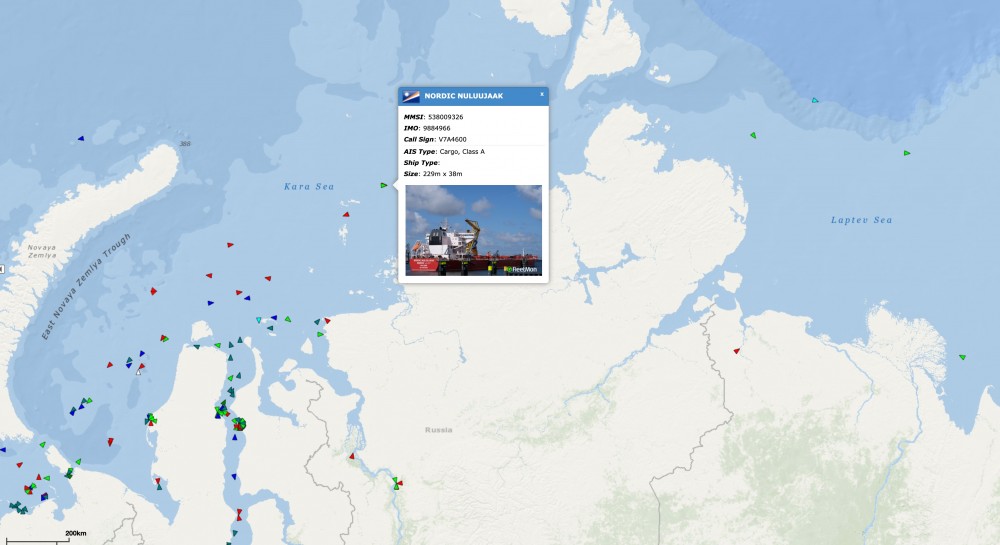

Mary River iron ore mine site on Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada, (Image courtesy of Baffinland Iron Mines.)

Baffinland Iron Mines has received a positive recommendation from the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB) to temporarily increase production at its Mary River iron ore mine in Canada’s Nunavut territory to 6 million tonnes through to the end of the year.

The decision, the company said, could help it keep the mine viable and save more than 1,100 jobs off the chopping block this fall.

Northern Affairs Minister Dan Vandal, however, has the final word and there hasn’t been any information on when that decision will come.

“Out of care and concern for the livelihoods of our employees and their families, we are delaying the issuance of termination notices until October 20th, which is the outside date the minister’s office has indicated it will be able to respond to the NIRB recommendation,” the company said.

While Baffinland is pleased about the NIRB’s decision, it is urging the minister to approve the production increase for the rest of the year.

Vandal is also still considering whether to approve Mary River’s Phase 2, which proposes a railway to Milne Inlet, as well as an increase in allowed shipments to 12 tonnes of iron ore a year, with eventual plans to increase that amount. The NIRB earlier rejected that plan.

Expansion detractors have argued for months that expanding the mine’s capacity would affect the world’s densest narwhal population.

Narwhals are a type of whale with a long, spear-like tusk that protrudes from its head. The marine mammal is an important predator in Eclipse Sound and other Arctic waters, as well a major food source for Inuit in the region.

Last year, a group of hunters from Arctic Bay and Pond Inlet blocked access to the mine in protest of the company’s ice breaking practices due to their negative impacts on narwhals. The company agreed to avoid ice breaking in spring, based on “the precautionary principle that is the foundation of our adaptive management plan,” Baffinland’s CEO said in a statement at the time.