Everyone thinks the Black Death was caused by bubonic plague. But they could be wrong – and we need to find the real culprit before it strikes again

By Debora Mackenzie 24 November 2001

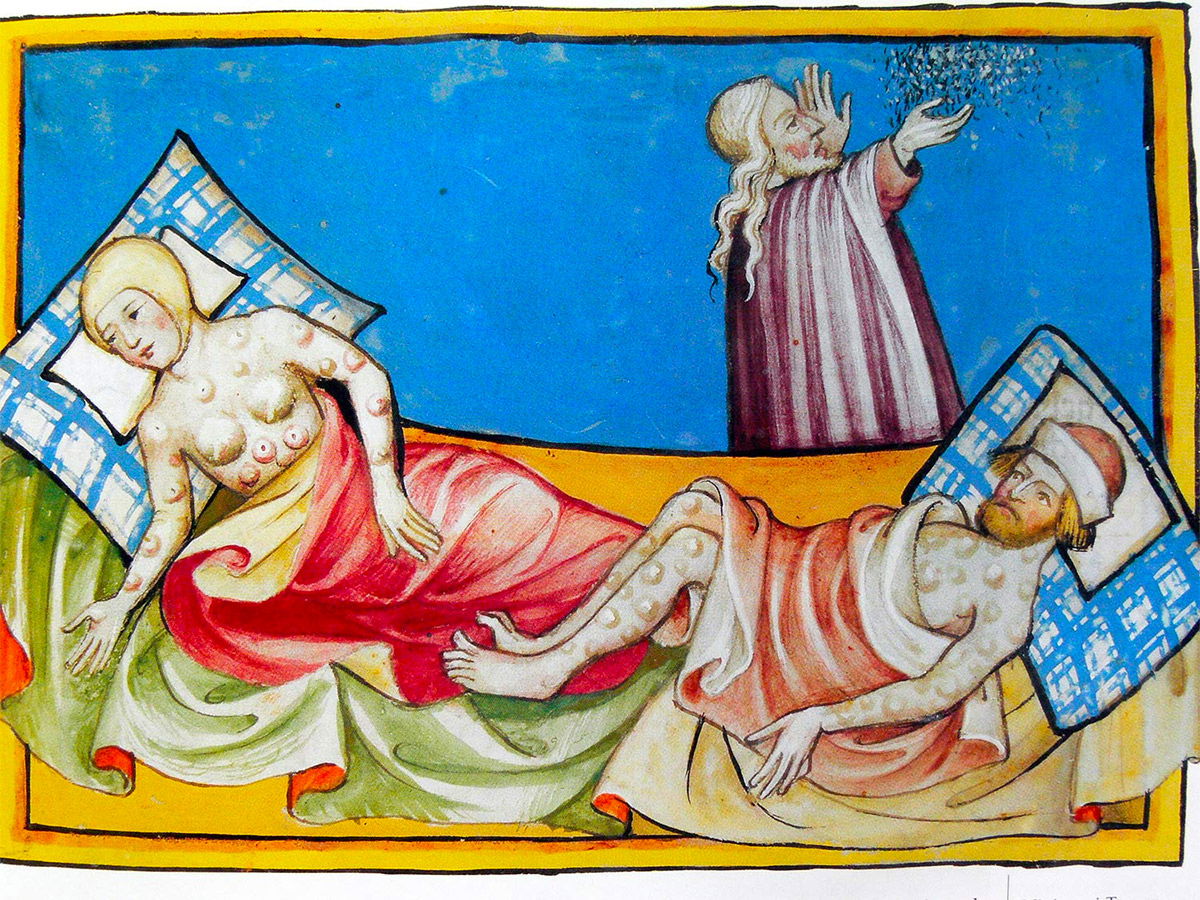

THE DISEASE that spread like wildfire through Europe between 1347 and 1351 is still the most violent epidemic in recorded history. It killed at least a third of the population, more than 25 million people. Victims first suffered pain, fever and boils, then swollen lymph nodes and blotches on the skin. After that they vomited blood and died within three days. The survivors called it the Great Pestilence. Victorian scientists dubbed it the Black Death.

As far as most people are concerned, the Black Death was bubonic plague, Yersinia pestis, a flea-borne bacterial disease of rodents that jumped to humans. But two epidemiologists from Liverpool University say we’ve got it all wrong. In Biology of Plagues, a book released earlier this year, they effectively demolish the bubonic plague theory. “If you look at how the Black Death spread,” says Susan Scott, one of the authors, “one of the least likely diseases to have caused it is bubonic plague.” If Scott and co-author Christopher Duncan are right, the world would do well to listen.

Whatever pathogen caused the Black Death appears to have ravaged Europe several times during the past two millennia, and it could resurface again. If we knew what it really was, we could prepare for it. “It’s always important to re-evaluate these questions so we are not taken by surprise,” says Steve Morse, an expert on emerging viral diseases at Columbia University in New York. Yet few experts in infectious diseases have even read the book, let alone taken its ideas seriously. New Scientist has, and it looks to us as though Scott and Duncan are on to something.

The idea that the Black Death was bubonic plague dates back to the late 19th century, when Alexandre Yersin, a French bacteriologist, unravelled the complex biology of bubonic plague. He noted that the disease shared a key feature with the Black Death: the bubo, a dark, painful, swollen lymph gland usually in the armpit or groin. Even though buboes also occur in other diseases, he decided the two were the same, even naming the bacterium pestis after the Great Pestilence.

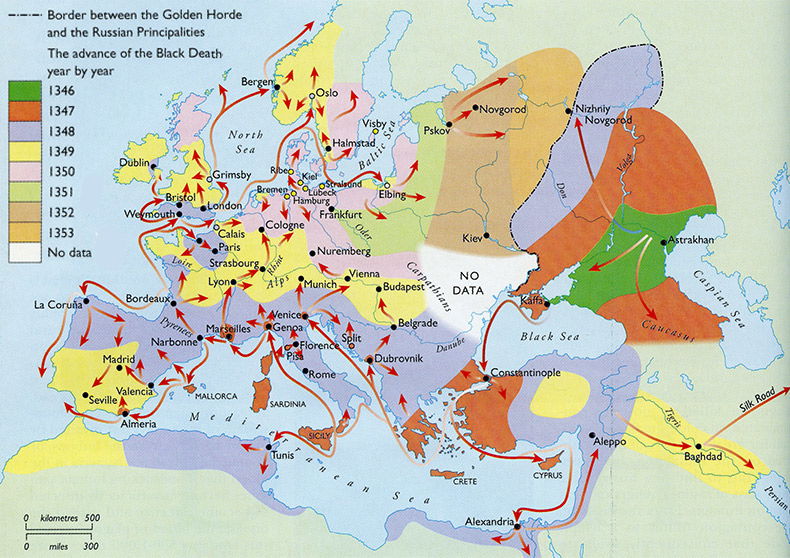

But the theory is riddled with glaring flaws, say Scott and Duncan. First of all, bubonic plague is intimately associated with rodents and the fleas they carry. But the Black Death’s pattern of spread doesn’t fit a rat and flea-borne disease. It raced across the Alps and through northern Europe at temperatures too cold for fleas to hatch, and swept from Marseilles to Paris at four kilometres a day – -far faster than a rat could travel. Moreover, the rats necessary to spread the disease simply were not there. The only rat in Europe in the Middle Ages was the black rat, Rattus rattus, which stays close to human habitation. Yet the Black Death jumped across great tracts of open country-up to 300 kilometres between towns in France-in only a few days with no intermediate outbreaks. “Iceland had no rats at all,” notes Duncan, “but the Black Death was reported there too.”

In contrast, bubonic plague spreads, as rats do, slowly and sporadically. In 1907, the British Plague Commission in India reported an outbreak that took six months to move 300 feet. After bubonic plague arrived in South Africa in 1899, it moved inland at just 20 kilometres a year, even with steam trains to help.

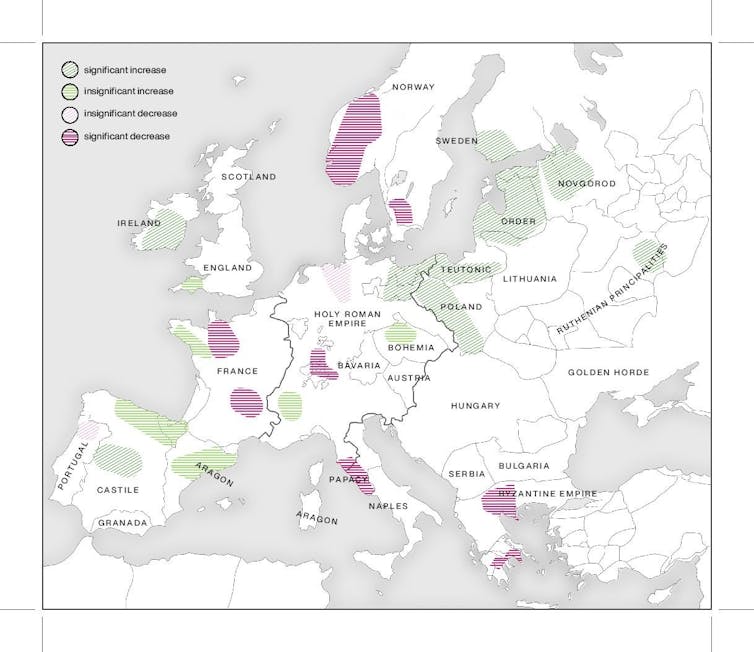

The disease that caused the Black Death stayed in Europe until 1666. During its 300-year reign, Scott and Duncan have found records of outbreaks that occurred somewhere in France virtually every year. Every few years, these outbreaks spawned epidemics that ravaged the rest of Europe. For Yersinia to do this, it would have to become established in a population of rodents that are resistant to the disease. It couldn’t have been rats, because the plague bacterium kills them-along with all other European rodents. As a result, Europe, along with Australia and Antarctica, remain the only regions of the world where bubonic plague has never settled. So, once again, the Black Death behaved in a way plague simply cannot.

Nor is bubonic plague contagious enough to have been the Black Death. The Black Death killed at least a third of the population wherever it hit, sometimes more. But when bubonic plague hit India in the 19th century, fewer than 2 per cent of the people in affected towns died. And when plague invaded southern Africa, South America and the south-western US, it didn’t trigger a massive epidemic.

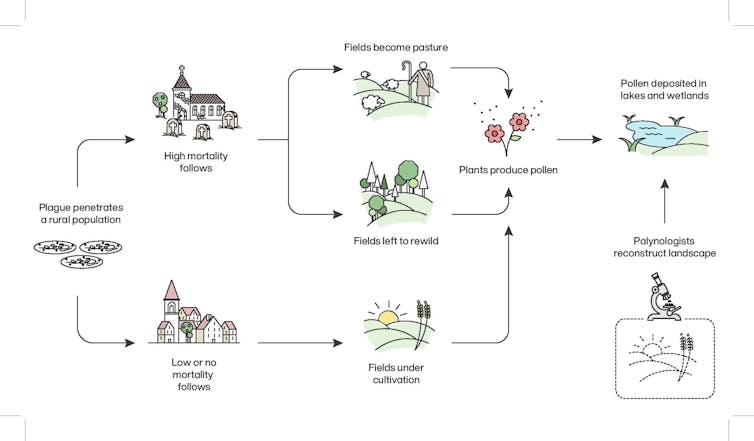

The most obvious problem with the plague theory is that, unlike bubonic plague, the Black Death obviously spread directly from person to person. People in the thick of the epidemic recognised this, and Scott and Duncan proved they were right by tracing the anatomy of outbreaks, person by person, using English burial records from the 16th century. These records, which detail all deaths from the pestilence by order of Elizabeth I, clearly show the disease spreading from one person to their neighbours and relatives, separated by an incubation period of 20 to 30 days.

The details tally perfectly with a disease that kills about 37 days after infection. For the first 10 to 12 days, you weren’t infectious. Then for 20 to 22 days, you were. You only knew you were infected when you fell ill, for the final five days or less-but by then you had been infecting people unknowingly for weeks. Europeans at the time clearly knew the disease had a long, infectious incubation period, because they rapidly imposed measures to isolate potential carriers. For example, they stopped anyone arriving on a ship from disembarking for 40 days, or quarantina in Italian – -the origin of the word quarantine.

Telltale timing

Epidemiologists know that diseases with a long incubation time create outbreaks that last months. From 14th-century ecclesiastical records, Scott and Duncan estimate that outbreaks of the Black Death in a given town or diocese typically lasted 8 or 9 months. That, plus the delay between waves of cases, is the fingerprint of the disease across Europe over seasons and centuries, they say. The pair found exactly the same pattern in 17th-century outbreaks in Florence, Milan and a dozen towns across England, including London, Colchester, Newcastle, Manchester and Eyam in Derbyshire. In 1665, the inhabitants of Eyam selflessly confined themselves to the village. A third of them died, but they kept the disease from reaching other towns. This would not have worked if the carriers were rats.

Despite the force of their argument, Scott and Duncan have yet to convince their colleagues. None of the experts that New Scientist spoke to had read their book, and a summary of its ideas provoked reactions that range from polite interest to outright dismissal. Some of Scott’s colleagues, for example, have scoffed that “everyone knows the Black Death was bubonic plague”.

“I doubt you can say plague was not involved in the Black Death, though there may have been other diseases too,” says Elisabeth Carniel, a bubonic plague expert at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. “But I haven’t had time to read the book.” Carniel suggests that fleas could have spread the Black Death directly between people. Human fleas can keep it in their guts for a few weeks, leading to a delay in spread. But this would be unlikely to have happened the same way every time.

Moreover, people with enough Yersinia in their blood for a flea to pick it up are already very sick. They would only be able to pass their infection on in this way for a very short time-and whoever the flea bit would also sicken within a week, the incubation time of Yersinia. This does not fit the pattern documented by Scott and Duncan. Neither would an extra-virulent Yersinia, which would still depend on rats.

There have been several other ingenious attempts to save the Yersinia theory as inconsistencies have emerged. Many fall back on pneumonic plague, a variant form of Yersinia infection. This can occur in the later stages of bubonic plague, when the bacteria sometimes proliferate in the lungs and can be coughed out, and inhaled by people nearby. Untreated pneumonic plague is invariably fatal and can spread directly from person to person.

But not far, and not for long-plague only becomes pneumonic when the patient is practically at death’s door. “It is simply impossible that people sick enough to have developed the pneumonic form of the disease could have travelled far,” says Scott. Yet the Black Death typically jumped between towns in the time a healthy human took to travel. Also, pneumonic plague kills quickly-within six days, usually less. With such a short infectious period, local outbreaks of pneumonic plague end much sooner than 8 or 9 months, notes Scott. Rats and fleas can restart them, but then the disease is back to spreading slowly and sporadically like flea-borne diseases. Moreover, pneumonic plague lacks the one thing that links Yersinia to the Black Death: buboes.

If the Black Death wasn’t bubonic plague, then what was it? Possibly-and ominously-it may have been a virus. The evidence comes from a mutant protein on the surface of certain white blood cells. The protein, CCR5, normally acts as a receptor for the immune signalling molecules called chemokines, which help control inflammation. The AIDS virus and the poxvirus that causes myxomatosis in rabbits also use CCR5 as a docking port to enter and kill immune cells.

In 1998, a team led by Stephen O’Brien of the US National Cancer Institute analysed a mutant form of CCR5 that gives some protection against HIV. From its pattern of occurrence in the population, they think it arose in north-eastern Europe some 2000 years ago-and around 700 years ago, something happened to boost its incidence from 1 in 40,000 Europeans to 1 in 5. “It had to have been a breathtaking selective pressure to jack it up that high,” says O’Brien. The only plausible explanation, he thinks, is that the mutation helped its carriers survive the Black Death. In fact, say Scott and Duncan, Europeans did seem to grow more resistant to the disease between the 14th and 17th centuries.

Yersinia, too, enters and kills immune cells when it causes disease. But when O’Brien’s team pitted Yersinia against blood cells from people with and without the mutation, they found no dramatic difference. “The results were equivocal,” says O’Brien. “We don’t know if the mutation protected or not.” Further experiments are under way. Similar mutations occur elsewhere in the world, but at nowhere near the high frequency of the European mutant. This suggests that pathogens such as smallpox exerted some selective force, but nothing like whatever happened in Europe, says O’Brien.

The association between CCR5 and viruses suggests that the Black Death was a virus too. Its sudden emergence, and equally sudden disappearance after the Great Plague of London in 1666, also argue for a viral cause. Like the deadly flu of 1918, viruses can sometimes mutate into killers, and then disappear.

But what sort of virus was the Black Death? Scott and Duncan suggest a haemorrhagic filovirus such as Ebola, since the one consistent symptom was bleeding. In fact they think “haemorrhagic plague” would be a good new name for the disease.

They are not the first to blame Ebola for an ancient plague. Scientists and classicists in San Diego reported in 1996 that the symptoms of the plague of Athens around 430 BC, described by Thucydides, are remarkably similar to Ebola, including a distinctive retching or hiccupping. Apart from that, many of the symptoms of that plague- – and one in Constantinople in AD 540 – -were similar to the Black Death.

Of course, the filoviruses we know about are relatively hard to catch, with an incubation period of a week or less, not three weeks or more. But there are other haemorrhagic viruses: Lassa fever in Africa is fairly contagious, and incubates for up to three weeks. Eurasian hantaviruses can incubate for up to 42 days, but are not usually directly contagious between people. Both can be as deadly as the Black Death.

Out of Africa

Perhaps we can narrow the search to Africa. Europeans first recorded the Black Death in Sicily in 1347. The Sicilians blamed it on Genoese galleys that arrived from Crimea just as the illness exploded. But the long incubation period means the infection must have arrived earlier. Scott suspects it initially came from Africa, just a short hop away from Sicily. That continent is historically the home of more human pathogens than any other, and the people who lived through the epidemics that wracked Athens and Constantinople said their disease came from there. The epidemic in Constantinople, for instance, seems to have come via trade routes from the Central African interior. “And I’m sure that disease was the same as the Black Death,” says O’Brien.

One way to solve the puzzle could be to look for the pathogen’s DNA in the plague pits of Europe. Didier Raoult and colleagues at the University of the Mediterranean in Marseilles examined three skeletons in a 14th-century mass grave in Montpellier last year (New Scientist, 11 November 2000, p 31). They searched the skeletons for fragments of DNA unique to several known pathogens-Yersinia, anthrax or typhus. They found one match: Yersinia. In their report they wrote: “We believe that we can end the controversy. Medieval Black Death was [bubonic] plague.”

Not so fast, says Scott. Southern France probably had bubonic plague at that time, even if it wasn’t the Black Death. Moreover, attempts by Alan Cooper, director of the Ancient Biomolecules Centre at Oxford University, and Raoult’s team to replicate the results have so far failed, says Cooper. Similar attempts to find Yersinia DNA at mass graves in London, Copenhagen and another burial in southern France have also failed.

It’s too early to conclude that the failure to find Yersinia DNA means the bacterium wasn’t there, though. The art of retrieving ancient DNA is still in its infancy, Cooper warns. Pathogen DNA – -especially that of fragile viruses – -is extremely difficult to reliably identify in remains that are centuries old. “The pathogen decays along with its victim,” he says. Scientists have had difficulty, for example, in retrieving the 1918 flu virus, even from bodies less than a century old and preserved by permafrost. And even if the technique for retrieving ancient DNA improves, you need to know what you’re searching for. There is no way now to search for an unknown haemorrhagic virus.

But the possibility that the Black Death could strike again should give scientists the incentive to keep trying. The similarity of the catastrophes in Athens, Constantinople and medieval Europe suggests that whatever the pathogen is, it comes out of hiding every few centuries. And the last outbreak was its fastest and most murderous. What would it do in the modern world? Maybe we should find it, before it finds us.

Further reading:Biology of plagues: Evidence from historical populationsby Susan Scott and Christopher Duncan, Cambridge University Press (2001)

Read more: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg17223184-000-did-bubonic-plague-really-cause-the-black-death/#ixzz6IBKqNk2x