Joel Shannon, USA TODAY

Sat, January 14, 2023

Two terms – climate change and global warming – point to the same existential threat: Global temperatures have risen dramatically in about the past 150 years and scientists say they're on pace to radically alter life on Earth in coming decades.

Temperatures on our planet have fluctuated based on natural processes many times in the past, but experts say this extraordinary run of warming is different.

Global temperatures already have risen about 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit since about 1850, NASA says.

In the past, it took roughly thousands of years for global temperatures to change that much.

Such rapid change is alarming and is already disrupting the delicate balance of life on Earth.

Even so, lies about climate change stubbornly persist.

The global warming trend comes as the human population exploded in recent centuries and technological advances spewed enormous amounts of chemicals and gases into the atmosphere. Some of them, called greenhouse gases, are excellent at trapping heat.

Here's what to know about climate change:

Is climate change the same thing as global warming?

Yes and no.

The terms have different meanings, although they're often used interchangeably, according to NASA.

While the term "global warming" was used frequently in the past, the term "climate change" is used more often today because it includes the cascading consequences of rising temperatures occurring around the world – melting glaciers, rising seas, drought and more. "Global warming" refers more narrowly to the trend of rising temperatures.

What is causing climate change?

The Earth's climate changes through a variety of natural processes, but federal scientists say the rapid warming experienced recently is primarily caused by human activities that emit heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

That's why global efforts to fight climate change are so focused on eliminating the burning of fossil fuels, the most notable source of harmful greenhouse gases.

CLIMATE CHANGE CAUSES: Why scientists say humans are to blame.

LATEST NEWS: What happened to California's drought?

What are 5 effects of climate change?

Rising seas: Warming temperatures heat up oceans, causing water to expand, and melt huge amounts of ice. The higher sea levels aren't just felt at the coast but also far inland along rivers.

Drought: A "megadrought" in the West has been supercharged by warmer temperatures and a lack of rain.

Wildfires: Drought provides ideal conditions for wildfires. What's worse: Fires release massive amounts of greenhouse gases, which fuels more climate change.

Rain: A USA TODAY analysis of a century of precipitation data shows how, east of the Rockies, more rain is falling – and in more intense bursts.

Hurricanes: Evidence shows climate change is causing wetter hurricanes, but scientists say more data is needed before settling questions over future frequency.

EFFECTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE: How they disrupt our daily life, fuel disasters

What's the latest climate change news?

In January, a grim accounting emerged of the world's extreme weather and climate disasters in 2022.

The nation's two federal agencies charged with weather and climate observations said in 2022:

Ocean heat reached a new high

Arctic sea ice was second lowest level ever recorded

Europe saw its second warmest year on record, but much of western Europe was the warmest ever

Contributing: Dinah Voyles Pulver

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: What is climate change and global warming? Definitions explained.

What are the effects of climate change? How they disrupt our daily life, fuel disasters.

Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY

Sat, January 14, 2023

Climate change makes splashy headlines when protesters hurl soup at priceless paintings or devastating floods wash through communities, but the impacts of warmer temperatures are also increasingly disrupting daily life.

Take a walk or ride a bike. Book a ski trip or attend an outdoor sporting event. Visit a big city or a cottage in the country. Chances are increasing that no matter what choice you make, you'll feel the effects of the warming climate.

Fall leaf peeping happens earlier. High school football teams take special precautions to keep kids cool. Inner cities set up chill zones to help protect citizens from heat waves.

How does climate change affect you?: Subscribe to the weekly Climate Point newsletter

READ MORE: Latest climate change news from USA TODAY

Heat waves are becoming more intense and flooding rains occur more often. Even so, lies about climate change stubbornly persist.

Here's what to know about the effects of climate change:

Climate change is real

No matter what your relatives or friends say or post on social media, experts say the mountain of scientific evidence continues to build.

What to know about climate change: What is global warming? Definitions explained.

What are the causes of climate change?: Why scientists say humans are to blame.

“It is virtually certain that human activities have increased atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases,” a national panel of experts concluded in a draft of the 5th National Climate Assessment released in November. They see high confidence in forecasts for longer droughts, higher temperatures and increased flooding.

JULY 28, 2022: Aerial view of homes submerged under flood waters from the North Fork of the Kentucky River in Jackson, Kentucky. Flash flooding caused by torrential rains has killed at least eight people in eastern Kentucky and left some residents stranded on rooftops and in trees, the governor of the south-central US state said.

While global average temperatures continue rising around the world, the U.S. has experienced more warming than many other countries.

EXTREME HEAT: Is the globe prepared?

WILDFIRES: Another above-average wildfire season for 2022. How climate change is making fires harder to predict and fight.

Warming sea surface temperatures around the globe provide more fuel for tropical storms and exacerbate the melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

Why is climate change important?

“Every part of the U.S. is feeling the effects of climate change in some way,” said Allison Crimmins, director of that 5th National Climate Assessment. Representing the latest in climate research by a broad array of scientists, the final version of the assessment is expected in late 2023.

The U.S. East Coast is feeling the combined impacts of more intense storms and rising sea levels. Sunny day flooding is reaching record levels.

Sea levels are forecast to rise as much as 10-12 inches by 2050. Federal agencies say it's a "clear and present risk."

Homes at the beach face an increased threat of erosion and a rising number of homes are giving way to the sea, but it's not just a coastal problem.

Disaster costs are rising, and scientists warn the window to further curtail fossil fuel emissions and put a lid on rising temperatures is closing rapidly.

Is there a climate crisis?

Many scientists and officials worldwide agree: Yes. By the end of this century, projections show global average surface temperatures compared to pre-industrial times could increase by as much as 5.4 degrees.

Merriam-Webster defines "crisis" as a time of intense difficulty, trouble, or danger. A mix of warmer temperatures, extreme rainfall and rising sea levels often make naturally occurring disasters worse, while droughts become more intense and heat waves occur more often.

“The climate crisis is not a future threat, but something we must address today,” Richard Spinrad, administrator of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said in August 2022.

Earth sets new emissions record: Dire global warming milestone could come within a decade, report says

Warmer waters: Rising seas could swamp $34B in US real estate in just 30 years, analysis finds

The term “climate crisis” has been used to describe these worsening impacts since at least 1986. Since the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was organized in 1988, its reports steadily have grown more dire.

In April, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said broken climate promises "put us firmly on track toward an unlivable world."

The Fourth National Climate Assessment, released during the Trump administration, warned natural, built and social systems were “increasingly vulnerable to cascading impacts that are often difficult to predict, threatening essential services.”

Climate extremes show: Global warming has 'no sign of slowing'

Is climate change getting better?

Experts say the warming climate will have increasingly severe impacts on daily life, making it more difficult to access water and food, putting a strain on physical and mental health and challenging transportation and infrastructure.

“Every increased amount of warming will increase the risk of severe impacts, and so the more (rapidly) we can take strong action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the less severe the impacts will be,” Cornell University professor Rachel Bezner Kerr said after the release of one recent IPCC report.

Heat kills more humans each year than floods or hurricanes.

Studies warn the growth in wildfires in the West could mean an increase in dangerous air quality levels.

Warmer climates put animals on the move and increases the risk they’ll spread pathogens to other animals and to humans. A group of University of Hawaii researchers looked at how 376 human diseases and allergens such as malaria and asthma are affected by climate-related weather hazards and found nearly 60% have been aggravated by hazards, such as heat and floods.

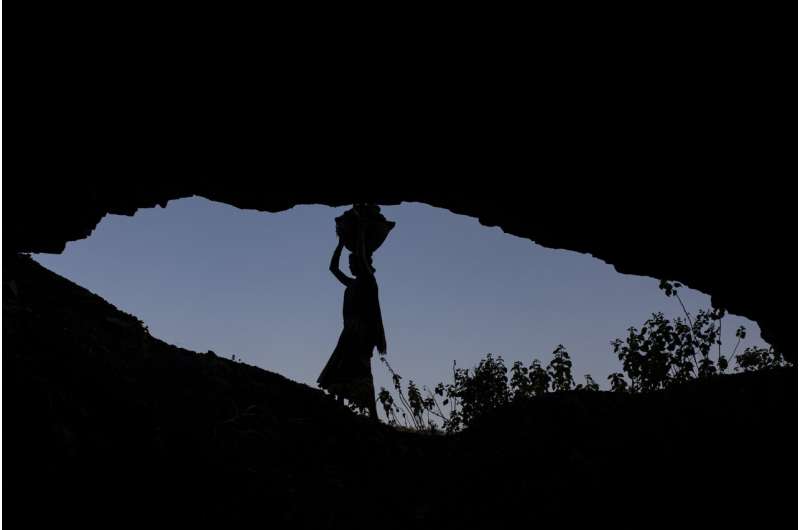

Climate change also is displacing people in the U.S. and across the globe.

How does climate change affect us?

Agriculture, sports events and community festivals are feeling the heat.

Farmers are seeing more weather extremes and wilder swings between extreme drought and flooding.

Maple syrup producer Adam Parke has seen a 10-day shift forward in the maple sugar season on his Vermont farm over three decades.

Beef, citrus and cotton: Agriculture sees effects of 'weirding weather' from climate change

NASA reported in 2021 that decreases in global food supplies related to climate change could be apparent by 2030.

But agriculture also may be part of the solution to countering the increases in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Billions set aside by the Inflation Reduction Act is earmarked to help support agriculture and reduce its emissions.

Changing climate: Uncertain future for Northeast maple trees, syrup season

Warmer spring temperatures have forced organizers to move historic flower festivals forward.

To see further impacts, take a look at the time-honored Olympic tradition.

Two months after the 2022 winter games concluded in Beijing, a group of Olympians visited Washington to ask members of Congress to act on climate change, which they see as a threat to their sports.

Athletes flag dangers of manmade snow.

Nordic skiing future uncertain.

Olympians worry as winter disappears.

The Summer 2024 Olympics are scheduled to kick off in July in France, where the country's meteorological officials expect 2022 to be its hottest year since records began in 1900. Meanwhile, the International Olympic Committee has delayed choosing the location for the 2030 winter games, in part over climate concerns.

Olympic host city selection on hold: Why? It may not be cold enough.

Even fly fisherman see changes all around them. “Everyone knows if this keeps up, the places we can fish for trout are going to be limited,” said Tom Rosenbauer of Vermont, whose job title at sporting goods retailer Orvis is chief enthusiast.

How does climate change affect animals?

Warmer temperatures are forcing some animal species to move beyond their typical home ranges, increasing the risk that infectious viruses they carry could be transmitted to other species they haven’t encountered before. That poses a threat to human and animal health around the world.

Heat's impact: Climate change could cause mass extinction of marine life in Earth's oceans, study says

A roseate spoonbill stands bright against the green of a southeast Arkansas swamp. Jami Linder, an Arkansas photographer, documented the first spoonbill nest in the state in 2020.

“Climate change and pandemics are not separate things,” epidemiologist Colin Carlson, told USA TODAY. “We have to take that seriously as a real-time threat.”

Invasive species are expanding their ranges and even native animals are changing their habits. In South America and Africa, some primate species are leaving the treetops more often.

In the U.S., roseate spoonbills, a brilliant pink wading bird, are moving north as temperatures warm and they're pushed out of native coastal habitats by rising sea levels.

“Climate change and pandemics are not separate things,” . “We have to take that seriously as a real-time threat.” and even native animals are changing their habits. In South America and Africa, some more often. In the U.S., roseate spoonbills, a brilliant pink wading bird, and they're pushed out of native coastal habitats by rising sea levels. Go deeper on climate change Climate change fact check: Trouble on the farm: Rogue waves?: It's not that funny: