Ellyn Lapointe

Thu, February 1, 2024

A giant "city killer" asteroid will safely shoot past Earth this Friday traveling at 41,000 mph.

Its closest approach to Earth will be 1.77 million miles, over seven times farther than the moon.

You can't see it with the naked eye but you can watch the event live on YouTube.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory has spotted a giant, "city killer" asteroid in space that's currently flying toward Earth. And this Friday, February 2, it will reach its closest approach to our planet, about 1.77 million miles away.

For reference, the moon is about 239,000 miles from Earth, so this asteroid will be 7.4 times farther than the moon. The speedy space rock is expected to be zipping along at about 41,000 mph and measures roughly 890 feet across or roughly the size of an entire US football stadium, according to NASA.

Experts sometimes call asteroids this size "city killers" because they are capable of destroying an entire city if they collide with an inhabited part of Earth.

Still, this asteroid will be too small and far away to see without a telescope on Friday. In fact, it will be about 10,000 times fainter than the faintest stars visible to the naked eye, Gianluca Masi, an astrophysicist and the scientific director of The Virtual Telescope Project, told Business Insider over e-mail.

But if you want to catch a glimpse of the asteroid as it whizzes by, you're in luck!

Masi and his colleagues at VTP will be recording the event live starting at 1 p.m. ET on Friday. You can watch their livestream on YouTube or in the video below:

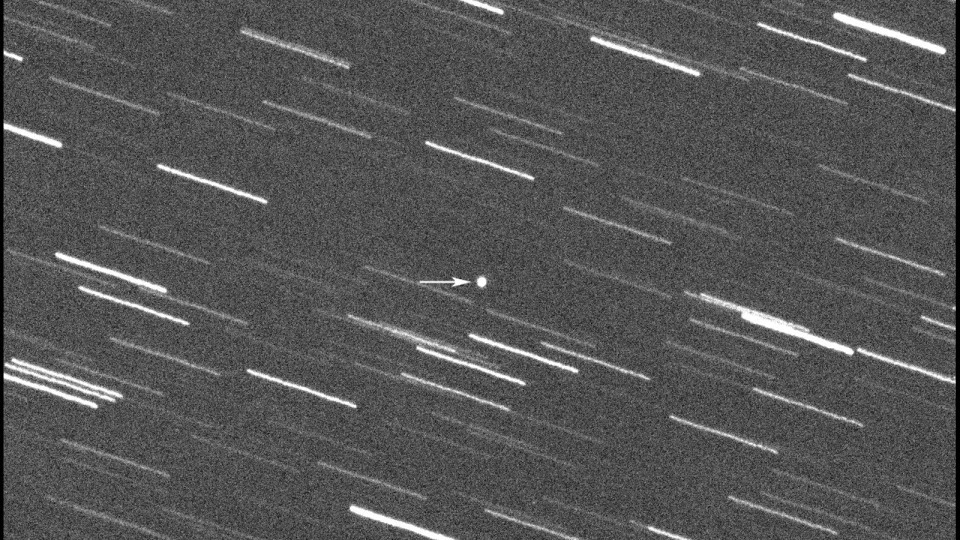

The livestream will track Asteroid 2008 OS7 as it flies by Earth. Viewers will be able to distinguish it as a tiny dot moving past other, fixed tiny dots, aka stars, in the background. The livestream will last about 45 minutes, Masi said.

VTP has recorded other flybys like this and it's "something always very fascinating to see," Masi told BI.

About asteroid 2008 OS7

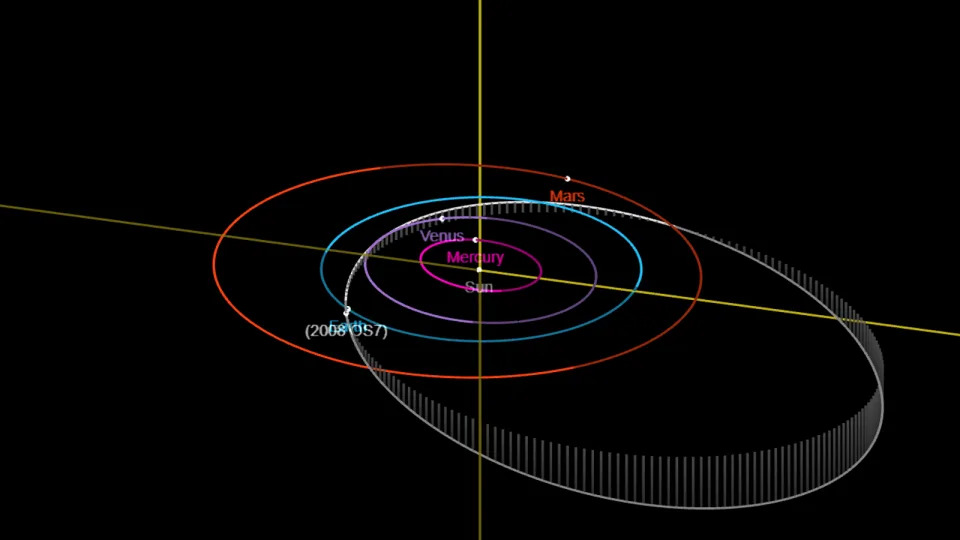

Asteroid 2008 OS7 orbits the sun every 962 days. After passing by Earth, it will continue along its oval-shaped path through our solar system.

Its oblong-shaped orbit means that each time the asteroid approaches Earth, its distance from our planet varies significantly.

For example, according to spacereference.com, upon its next closest approach in July 2037, it will be about 9.7 million miles away from Earth — nearly 5.5 times farther than during Friday's encounter.

Potentially hazardous asteroids

Asteroid 2008 OS7 is what NASA calls a "potentially hazardous" asteroid because of its size and how close it flies past Earth.

An asteroid is considered "potentially hazardous" if it is at least 460 feet in diameter and orbits Earth within a distance of about 4.65 million miles.

Scientists have identified more than 34,000 near-Earth objects. As of August 2023, just over 2,300 have been designated potentially hazardous, Space.com reported.

But NASA suspects there are many more out there that have yet to be discovered. If a giant asteroid was on course to hit Earth, we'd need 5-10 years warning to destroy or deflect it.

NASA JPL is currently working on the Near-Earth Object Surveyor mission, set to launch in September 2027 and send an infrared space telescope into Earth's orbit to expand NASA's search for near-Earth objects that could potentially threaten our planet.

'City killer' asteroid will make its closest approach to Earth for centuries this Friday (Feb. 2)

Thu, February 1, 2024

An asteroid floating in space with Earth and the sun in the background.

A "potentially hazardous" football stadium-size asteroid will zip safely past Earth on Friday (Feb. 2), and, in doing so, will reach its closest point to our planet for more than 100 years. It will also be at least several centuries before the space rock ever gets this close to us again.

The massive asteroid, named 2008 OS7, is around 890 feet (271 meters) across and will pass by Earth at a distance of around 1.77 million miles (2.85 million kilometers), according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). For context, that is more than seven times further away than the moon orbits Earth.

You can watch the asteroid flyby for yourself thanks to a live stream from The Virtual Telescope Project, which will begin at 1:00 p.m. ET on Feb. 2.

As it passes by Earth, the asteroid will be traveling at a speed of around 41,000 mph (66,000 km/h), according to JPL.

To compare this space rock's girth to that of other asteroids, it is around half the size of asteroid Bennu, which NASA visited and took samples of, and at least 70 times smaller than the Vredefort meteor — the largest known space rock to ever hit Earth.

Related: 'Planet killer' asteroids are hiding in the sun's glare. Can we stop them in time?

A balck and white image of an asteroid streaking through the stars

Due to its size and proximity to Earth, the asteroid is classified as potentially hazardous despite the fact it will never come close enough to impact our planet, JPL predictions show. If the space rock did ever crash to Earth, it is big enough to wipe out a large city, such as New York.

However, the object isn't hefty enough to be considered a "planet killer" asteroid, such as the Vredefort meteor or the space rock that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

NASA has identified around 25,000 potentially hazardous asteroids, although a significant percentage of these are not as large as the impending space rock. One of these deadly asteroids is expected to hit Earth every 20,000 years, Live Science previously reported.

An orbital diagram showing the asteroids trajectory through the solar system.

2008 OS7 has a highly elliptical orbit, meaning that it does not orbit evenly around the sun. Because of this, the distance between it and Earth varies wildly whenever the space rock makes a close approach to our planet. For example, when the asteroid approached us shortly after its discovery in 2008, it was around 55.9 million miles (90 million km) away from us, which is more than 30 times further away than it will be this week, according to JPL.

related stories

—The 8 most Earth-shattering asteroid discoveries of 2023

—How long can an asteroid 'survive'?

—NASA's most wanted: The 5 most dangerous asteroids in the solar system

Scientists have only directly observed the asteroid fly by Earth twice before. But based on the space rock's orbital data, JPL has simulated every close approach the asteroid has made since 1900 and predicted every close approach it will make until 2198. At no other point in this nearly 300-year dataset is the asteroid expected to be closer to our planet than on Feb. 2 this year.

Several other asteroids have made close approaches to or directly hit Earth in the last few weeks.

On Jan. 27, an airplane-size asteroid passed by Earth at a distance of just 220,000 miles (354,000 km), which is slightly closer than the moon is to our planet. And on Jan. 21, a child-size asteroid was discovered by astronomers around 3 hours before it exploded in the atmosphere above Germany.